8 January 2026

Competitiveness, resilience or preparedness – the big imponderables for European trade in 2026. Independent trade economist Dr Rebecca Harding explains why diverse and resilient supply chains are key – and how these should be financed

MINUTES min read

In September 2025 the Draghi report, which laid the foundations for a renewed drive to improve European competitiveness, had its first anniversary. The report identified a productivity gap with the US which, it argued, was “existential” for the European project.1

This productivity gap would only be closed with public and private investment of nearly 5% of European GDP, a strong focus on innovation in critical technologies, a more integrated single market, streamlined regulation, a shift in industrial policy to create ‘European champions’, and a clear focus on energy transition and security to reduce dependency on Russian supplies.

It was a wake-up call: unless Europe’s businesses and policy makers addressed these gaps quickly and forcefully, the European economy would come under increasing pressure from China over capacity and supply chain dominance, and the greater innovative capacity of the US and China; for example Chinese businesses now compete directly with European exporters in 40% of global markets, whereas in 2002 it was just 25%.2 In short, unless Europe completely re-thought its economic model, it could expect its global trade and economic performance to diminish over time.

More than one year on, Mario Draghi, the report’s author and former European Central Bank President, does not rate the progress that the EU has made. In September 2025, speaking at a European Commission conference in Brussels, he argued that Europe has fallen further behind, despite the importance of the challenge.3 The report recommended 885 measures that would improve capital markets, strengthen supply chains and improve regulatory frameworks, but only 11% had been implemented.4 In their September 2025 report, Need for speed – the Draghi report one year on, Deutsche Bank Research analysts Marion Muehlberger and Ursula Walther rated the impact of some 18 of those measures, with 16 rated as “incremental” or “limited” and only two as a substantial reform.5

Given the urgency of the problems faced by Europe, why, then, does there not seem to be any equivalent sense of urgency to trigger the size of the structural and strategic changes that Europe needs?

Unintended consequences

My own discussion with Deutsche Bank’s Head of Corporate Bank and Investment Bank, Fabrizio Campelli at Sibos 2025 highlighted the complexity of the challenges that Europe faces. It is worth bearing many of these in mind at the start of 2026.6 For example, Europe needs to be acutely aware of the unforeseen consequences of any decisions it makes to become more competitive.

Take wages for example – if Europe tries to compete with China on prices, this will have an impact on wages across the region. Lower wages make it more difficult to push innovation, research and development or broader organisational change. From a political point of view, it also increases the risk of greater swings towards populism because people see their purchasing power diminished and blame incumbent politicians as a result, argued Campelli.

Security spend ramp-up

Quite apart from this complexity, it is also important to realise that the geopolitical context of 2025 is very different to 2024. There is still a military war on the border of the bloc that has focused European minds on defence and security like never before. Furthermore, when the US made clear the re-orientation of its security policy away from Europe at the Munich Security Conference, this has since galvanised nations to reconsider their spending priorities.7

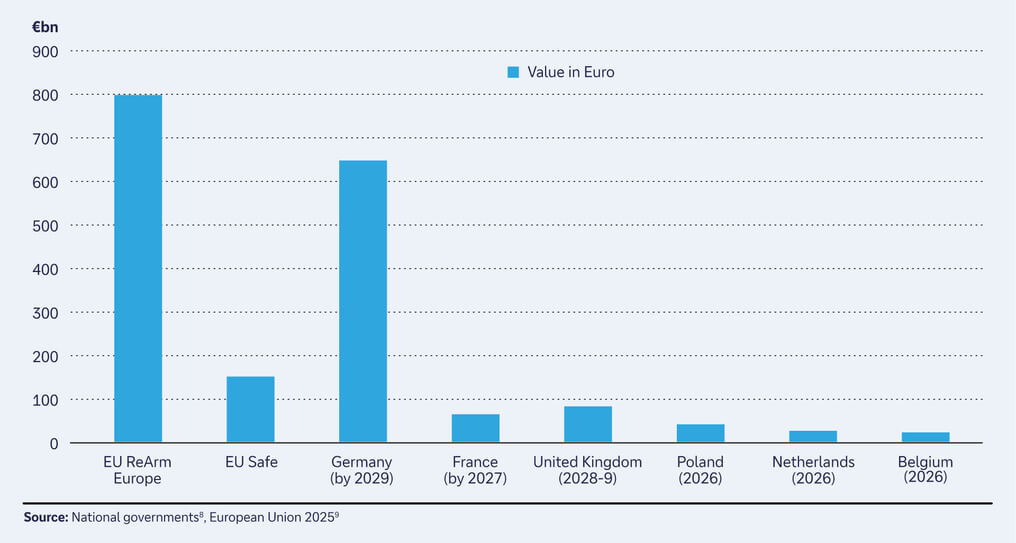

The evidence for this can be seen in the amounts that governments across the region have committed to defence, security and infrastructure since then (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: European Union (+UK) expected expenditure on defence (€bn)

Source: National governments8, European Union 20259

Germany is quite clearly the biggest spender after the EU and the defence expenditure of more than €600bn will be accompanied by €500bn for infrastructure and a further €100bn from the Zeitenwende fund set up to enable accelerated transition to the new realities that Germany faces.10 Poland will have committed nearly 5% of its GDP to defence by the end of 2026 and, while the time frames differ between countries, the fact that these are the increases that governments are planning suggests that a structure change in the economies of Europe is imminent.

The sense of urgency at a national level is coming from two key challenges in addition to waning competitiveness, and are ones most corporates and their financiers would at least recognise:

- Europe is responsible for funding its own defence and security. The role that the US is willing to play in supporting Europe through NATO is significantly less than it has played in the past, as was made clear by the US National Security Strategy published at the end of November 2025.11

- Europe’s competitiveness also has to be seen against a backdrop of an economic security threat. This that strikes at the heart of the multilateral, free-market values that it has espoused for the last 80 years since the end of the Second World War.12

Embedded into European institutions from the Treaty of Rome onwards is the principle that greater integration through business, and specifically trade, will create economic prosperity and prevent war between European nations.13 Within this broad framework are the principles of fairness, equality, openness and peace that are under threat from a succession of cheap alternatives from China and, equally as importantly, the changing nature of the trade relationship with the US, particularly in the last year but evident rhetorically for much longer than that.14

So, what does all this mean? The NATO agreement for European governments to spend 5% of their GDP on military equipment is potentially exactly the boost to public and private sector investment that the Draghi report envisaged. However, the mechanisms by which this expenditure is distributed will determine how effective it will be in improving the competitive performance of the region.

Beyond more debt and taxation

Traditional economic estimates suggest growth multipliers of 0.4–0.8 for advanced economies, meaning that each dollar of spending adds less than a dollar to GDP in the short run. In some cases, especially when funds go to wages or imported equipment, the impact may be close to zero and much depends on how that money is raised – increasing debt will put a burden on national budgets, while increasing taxation will put a burden on the populations of each nation.15

“Debt and taxation can only be short-term solutions”

So, if there is to be a real difference in how all this money being poured into defence genuinely improves competitiveness and increases growth, then debt and taxation can only be short-term solutions. Instead, the way defence spending is structured makes all the difference to the economic impacts that spending will have. And here, financial institutions and the way in which they work together with export credit agencies, sovereign funds and supply-chain guarantees, make a core difference.

Put simply, if the financing of the expenditure means that money gets to the small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), the innovators and the industrial base in supply chains, the effects are larger, more persistent, and more likely to deliver long-run productivity gains because they enable growth from within the economic system through greater research and development, skills acquisition and innovation.16 In fact, the growth multiple could be as large over a 10-year period as four times the rate of a simple injection of cash by a government.17

This is because the supply side adjusts more quickly to meet the demand that the government has laid out in its defence spending plans. The approach is important for Europe, not least because it currently brings in some 64% of its defence supply chains from the US and is therefore not as independent as its policy makers would want it to be.18

“Banks can enable the process of accelerating European competitiveness”

Role of financial institutions

Finance has a key role to play in enabling these wider structures to develop quickly. Once banks have become comfortable with the need to support SMEs within Critical National Infrastructures (CNIs), they can enable the process of accelerating European competitiveness. These CNIs do not just comprise defence and security but energy transition, food security and climate security as well.

To do this, they need to work with national and international economic development finance institutions, such as the Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau in Germany, to ensure that money gets directly to the smaller businesses that can deliver the scaling up of industrial production that European competitiveness so desperately needs. These sovereign and international financial organisations are designed to reduce the risks for both the providers of credit and the businesses users of that credit.

European competitiveness has long been an issue, and this does not look like changing in 2026. The Draghi report was not the first wake-up call to European policy makers, corporates and financial institutions and it almost certainly will not be the last. However, the circumstances that Europe now finds itself in, which will become more acute in the coming year, are not just about competitiveness. To meet the very real need for defence and security, Europe now needs resilient supply chains.

To achieve this, the financial and economic structures must be prepared in a way that allows trade and supply chain finance, and working capital, to get to the right place at the right time in a supply chain. This is what banks do – they hold the key to ensuring that a prepared economy is also a resilient and competitive economy.

Deutsche Bank Research reports referenced

Need for speed – the Draghi report one year on, by Marion Muehlberger and Ursula Walther

Sources

1 See The future of European competitiveness at commission.europa.eu

2 See The future of European competitiveness; p. 14 at commission.europa.eu

3 See High Level Conference – One year after the Draghi report: what has been achieved, what has changed at commission.europa.eu

4 See The unfortunate EU foot-dragging on the Draghi plan at ft.com

5 See Need for speed - the Draghi report one year on at dbresearch.com

6See Dawn of Europe’s new trade order? at flow.db.com

7 See Munich Security Conference 2025: Speech by JD Vance and Selected Reactions at securityconference.org

8 See Germany approves 2025 budget, ushering in new era of spending at reuters.com; See UK defence spending at parliament.uk; See Poland's 2026 budget breaks records with massive defence spending at devere-europe.com, See Italy’s sudden defense-spending uptick lacks details, economist finds at defensenews.com; See What to Make of Macron’s Recent Defence Spending Commitments?at rusi.org

9 See ReArm Europe Plan/Readiness 2030 at europarl.europa.eu

10 See Policy statement by Olaf Scholz, Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany and Member of the German Bundestag, 27 February 2022 in Berlin at bundesregierung.de

11 See National Security Strategy of the United States of America November 2025 at whitehouse.gov

12 See Rebecca Harding (2025): The World at Economic War: How to Create Economic Security in a Weaponised Global Economy London Publishing Partnership.

13 See Treaty of Rome (EEC) at eur-lex.europa.eu

14 See Trump trade – back to the future? at flow.db.com

15 This section is drawn on a meta-analysis of defence spending impacts conducted for this article. See for example, Becker, D. and Dunne, P. (2023) ‘Components of defence expenditure and growth’, Defence & Peace Economics. Olejnik, A. (2023) ‘Military expenditure multipliers in Central and Eastern Europe’, Journal of Comparative Economics, 51(3). SUERF (2025) Buy guns or roses? Fiscal multipliers of defence spending in the EU. SUERF Policy Note No. 372. Moura, A. (2015) Fiscal multipliers and endogeneity bias. Toulouse School of Economics Working Paper. Geli, J. and Moura, A. (2023) The gritty of fiscal multipliers. IMF Working Paper. Dudzevičiūtė, G. (2023) ‘Does the funding of the defence sector depend on economic factors in the long run? The cases of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania’, Public Policy and Administration, 22(3), pp. 267–277. doi:10.5755/j01.ppaa.22.3.34022.

16 Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt, 1997, Endogenours Growth Theory MIT Press Cambridge, Mass.

17 See Financing defence for growth and resilience at rebeccanomics.com

18 See SIPRI Fact Sheet March 2025: Trends in International Arms Transfers, 2024 [EN/CA/SV] at reliefweb.int