29 July 2025

Dr Rebecca Harding looks at the issues in – and beneath – the Arctic Circle and its impact on the global economy

MINUTES min read

In 2016, a Bloomberg article declared the Arctic Ocean the “trillion-dollar ocean”.1 Oil, gas and mineral reserves in the Arctic Circle were argued to total this sum of money. Perhaps as a result, what was seen by most as a vast tract of frozen land and ice, populated by Inuit indigenous peoples and polar bears, has become the centre of geostrategic attention. The two key drivers behind this are:

- The rate at which Arctic ice is melting and opening up new commercial opportunities

- The return of the ‘Great Power Competition’ which has the region as its focus.

There is some scepticism that the promised critical mineral wealth of the region will materialise, based on cost and timescale grounds.2 Even if it does, there are huge potential environmental costs associated with it.

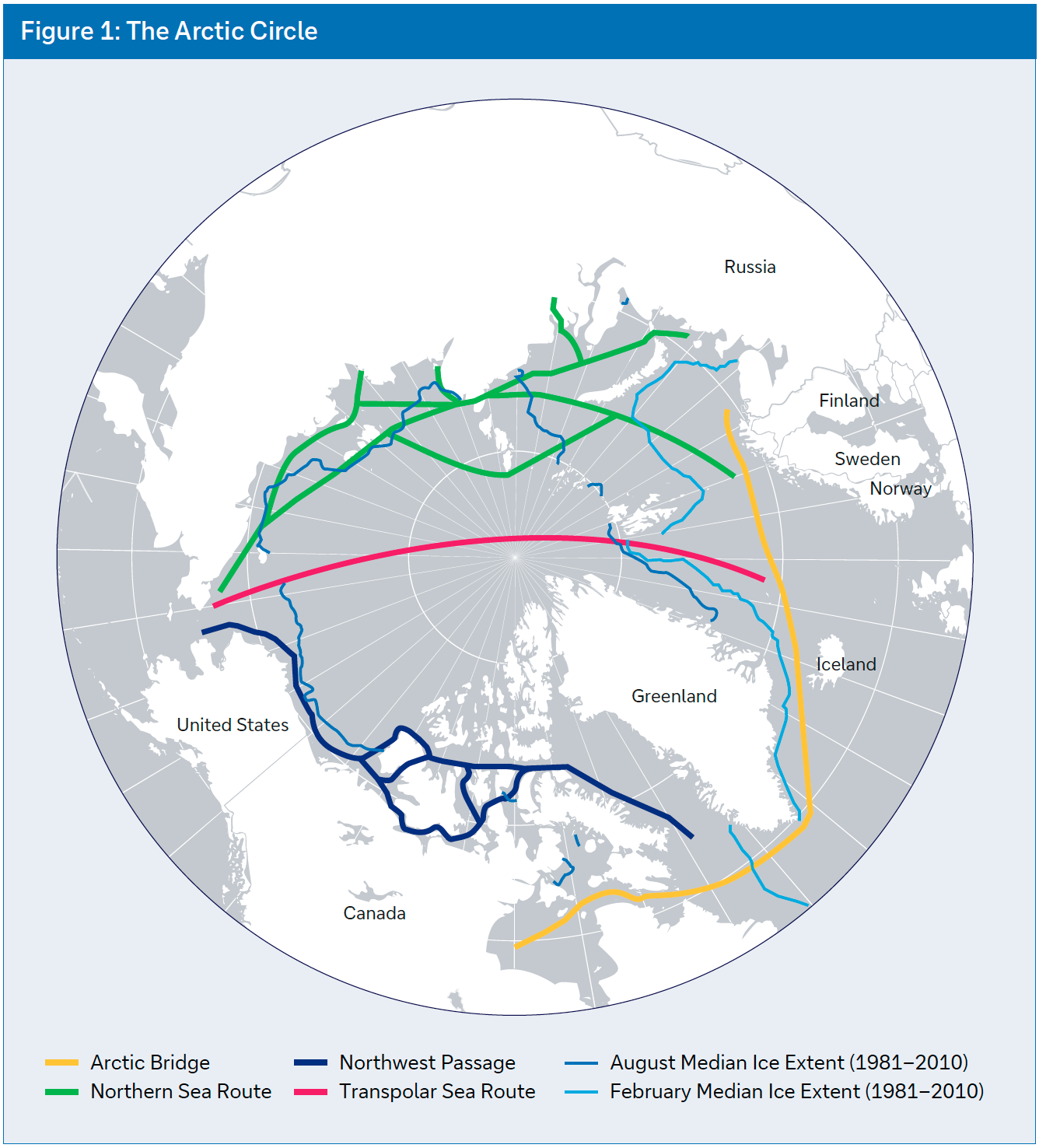

Shipping already runs through the Arctic Circle3 via Canada (the Northwest Passage – NWP) and Russia (the Northern Sea Route – NSR). Canada has an indefinite moratorium on exploration or development of its part of the Arctic Circle and the NWP has never been a viable trade route because of the quantities of ice and the environmental restrictions on it. In contrast, President Putin sees the NSR as an opportunity to potentially send 100 million tonnes of cargo through the Arctic Circle.4 This would increase the quantity of shipping-related black carbon emissions and therefore speed up the rate at which Arctic ice caps melt.

However, the combination of geopolitics and rapidly warming temperatures (global environmental charity WWF estimates that the rate of warming in the Arctic is four times the global average)5 mean that this region is likely to have a dramatic effect on our economic, climate and defence security in the coming years. There are difficult choices ahead; this article summarises what’s at stake.

Geopolitical tensions

Attention on the region has become more pronounced since 2022, when Russia was suspended from the Arctic Council, which consists of the countries bordering the Arctic Circle: Canada, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden, the US, and a representation of indigenous peoples’ leaders. Up to that point, the region was considered neutral and the Arctic Council had no formal treaty, with its operations largely confined to climate research which relied on data collection by the indigenous population and international scientists, including Russian nationals. Once Russia’s membership was suspended, these projects ceased immediately, pushing the Arctic Council into a geostrategic rather than scientific role.6

Russia changed its own Arctic policy as a result, removing all mention of the Arctic Council from previous policy documents and laying claim to the continental shelf beyond 200km from its Arctic coastline. This has been upheld by the UN’s Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf, extending its exclusive economic zone far beyond those claimed by other Arctic Council members.7 In addition, Russia has declared that no vessel may pass through this zone without the permission of Russian maritime authorities (although Chinese vessels are exempted) and it now has more military bases in the Arctic Circle than NATO.8

Russia is focusing on new strategic cooperation with China, not least through its Arctic Liquefied Natural Gas 2 (Arctic LNG 2) platform in which China has invested US$20bn, and a new research station on the Norwegian archipelago of Svalbard with other BRICS nations.9 Russia has explicitly stated its wish to exploit some 400 oil and gas reserves.

China has declared itself a “near Arctic nation” and in 2018 launched its Arctic strategy to develop a ‘Polar Silk Road’. It has been working with Russia to create an alternative shipping route through the NSR.10 It regards the NSR as a more cost-effective alternative to the Suez Canal, and potentially more environmentally friendly (once finished, it would reduce the journey time from China to Europe by around nine days).11

Since the change of US administration in January 2025, there has been a renewed focus on the Arctic Circle, with President Trump arguing in an interview at the end of March that Greenland is essential for US security. This develops a perception that has been building in the US since 2009 that the Arctic Circle is strategically important for economic security and defence because of the dominance of Russia in the region compared to NATO capability.12

Canada is increasingly being urged by commentators13 to accelerate its December 2024 Arctic Foreign Policy strategy14 and prioritise its position as a key regional player in the Arctic Circle. Here the emphasis is on both economic security, through greater investment in deep water ports, and national security through a sustained military presence.15 Canada’s strategic approach to the region back in 2019 was predominantly focused on environmental protection and research. However, its 2024 Arctic Circle strategy focused explicitly on the need to see the region as strategic in foreign policy, with hard military investment alongside diplomacy necessary to maintain regional stability.16

“There is scepticism that the promised critical mineral wealth of the region will materialise. Even if it does, there are huge potential environmental costs”

Economic considerations

The Arctic Circle accounts for just 0.7% of the world’s GDP, with an annual output of US$500m. The WWF estimated in 2018 that the region will need around US$1trn of investment – spread across renewable energy projects, rail, maritime and municipal buildings – to realise its full potential without causing significant damage to the already melting ice caps.17 So how much of this is now in the pipeline?

Numbers are hard to come by, but China is estimated to have invested at least US$90bn in the region, including a US$10bn investment in Russia to explore and develop the NSR between 2013 and 2022. Two Chinese businesses, the China National Petroleum Corporation and the Silk Road Fund, hold a 10% stake each in the Russian Arctic LNG 2 project and 20% of the Yamal LNG project, which are currently subject to international sanctions. These companies could well invest more into Arctic projects if the 10% Russian tax on dividends is reduced or abolished.18

Russia’s is the economy that is the most dependent on the Arctic Circle. The region generates around 70% of its oil revenues and 80% of its gas reserves – it is not all under an ice cap. Russia obtains 20% of its GDP from the region and 30% of its exports originate there. It has invested some US$19bn in infrastructure.19

The sanctions against Russia have increased its dependency on China. However, China has not invested in its Polar Silk Road initiative much beyond its 2018 objectives, which were to conserve the region, conduct research and take advantage of it commercially in line with international law.20 Russia, however, has explicit and current objectives to exploit oil and gas in the region and build its military presence there.21

This rhetorical disconnect is creating tensions between China and Russia in the region, not least because much of the investment funding has come from China and is now on hold. Russia itself is not currently in a position to invest significantly in long-term oil and gas extraction anywhere, given its ongoing military expenditure.22 There is growing commentary suggesting that Russia is open to cooperation with the US in exploiting the region’s resources.23 This may reflect Russia’s own need for investment as much as any strategic realignment of its interests, given this would reduce its reliance on Chinese investment.

Mineral resources

Despite their magnitude, the Arctic Circle’s mineral resources have hitherto been very hard to exploit because of the climatic conditions there. For this reason, they need to be of a high value threshold to justify the added risk to capital that extracting them represents.24 However, increasing accessibility because of ice melting and renewed attention on its critical mineral deposits have altered national priorities.

According to the WWF, Arctic ice is being lost at a rate of 13% per decade. If emissions rise unchecked, it argues, the region could be ice-free in summer by 2040,25 with the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change estimating that it could be entirely ice-free by 2050.26 This makes the NSR navigable and a viable alternative to other, longer routes from the Southern Hemisphere to the Northern Hemisphere, such as the Suez Canal. It also reduces the capital risk involved in extracting minerals in the region.

Energy transition, electronics, aircraft, and defence and security equipment all rely on critical minerals. The Arctic Circle accounts for around 10% of the global production of nickel, platinum and palladium, for example. But major investment will be needed to capitalise on such potential.

There is huge potential in the region, but it is likely that a lot of production, in the short term at least, will come from existing mines and facilities. This is because conditions for exploiting undiscovered reserves are not good, even with ice caps melting as quickly as they are. This means it will take longer than is currently estimated without a significant investment in infrastructure. At present, that investment is nowhere near the required level, due to a combination of the constrained Russian economy, the economic climate in China and its caution regarding sanctions on Russia, and the fact that Europe, Canada and the US have historically under-invested in the potential of the Arctic.

Energy and critical mineral potential between Alaska and Russia

- The US geological survey estimates that undiscovered oil and gas in the region could amount to 22% of the world’s total production, or around 412 billion barrels of oil.27

- The Arctic Economic Council estimates that 31 out of 34 of the critical minerals required for energy transition are in the Arctic Circle.28

- There are 400 oil and gas fields in the North Arctic Circle. The US, Canada and Russia already extract some 2.6 million barrels of fossil fuels a day from the region. This accounts for 10% of the world’s supply of oil and 25% of its supply of gas.29

- An estimated US$1.5trn–US$2trn worth of critical minerals is in Russia.

- Canada has the potential to access large reserves of copper, gold, molybdenum, lead and uranium.

- Melting ice in Greenland is exposing mineral belts that may contain critical metals including platinum, nickel, lead, zinc, gold and rare earths.

Source: geographical.co.uk

Diverting trade

An operational Sino-Russian shipping corridor has been open since July 2023 and China previously sent approximately 80 ships a year through the region until 2023, when sanctions against Russia made this difficult. Most shipping is in oil and LNG and there is no container trade at present.

The attractiveness of the NSR rests in the fact that it shortens travel time between the Southern and Northern Hemispheres, thereby reducing costs by some 25% and travel time by around 40% compared to the equivalent journeys through the Suez Canal.30

The viability of the Arctic Circle as an alternative trade route will depend entirely on the speed at which ice melts, and at what point sending container ships as well as cargo ships through the NSR year-round becomes possible. In 2022, around 1,700 ships went through the Arctic, compared with 23,000 through the Suez Canal and 14,000 through the Panama Canal.31 Some 41% of these are fishing vessels.32 At present, as is the case with the natural resources in the region, the costs of exploiting its economic potential as a trade route will be high, and perhaps too high to be feasible. But the costs are not just those of exploration.

On thin ice?

Water depth in Russia’s Arctic coastal exclusive economic zone is just 200 metres and the climate risks of more traffic through the region cannot be understated. Beneath the sea floor are ice sheets, below which lie substantial methane deposits. These are already leaking and releasing greenhouse gases (GHG) into the atmosphere,33 and this effect is worsening as more shipping traverses the shallow waters. The risk of a vicious circle where increased shipping accelerates GHG emissions, speeding up the melting of ice caps and allowing more shipping through, is clear.

Added to this, there are increasing numbers of icebreakers in the Arctic Circle as NATO countries try to address the asymmetry between their icebreaker fleets and Russia’s. Russia has scores of icebreakers, China has four, and the US has just one.34 This presents another environmental risk since, by definition, icebreakers break ice: every icebreaker creates around 7km of broken ice (effectively ice cubes, which melt more quickly and therefore accelerate the melting process).

The escalating threat of the Great Power Competition in the Arctic Circle is there to see. From the analysis here, it is not clear that this is genuinely about either access to minerals or, indeed, the advantage of shorter and cheaper trade routes, for the simple reason that this potential will take time and significant investment to realise.

It is worth pointing out that many of the estimates of the extent to which the economic and natural resources of the region can be unlocked are a few years old. Recent commentary is more focused on the geostrategic game that is playing out between China, Russia and the US.

Whatever happens, the risks in the Arctic Circle are significant. As the Great Power Competition heats up along with the temperatures, both pose a threat to the potential of the “trillion-dollar ocean”.

Dr Rebecca Harding is an independent trade economist and a regular contributor to trade publications

Sources

1 See bloomberg.com

2 See oxfordenergy.org

3 See arcticwwf.org

4 See climatetrace.org

5 See arcticwwf.org

6 See foreignpolicy.com

7 See ejiltalk.org

8 See reuters.com

9 See newsweek.com

10 See aljazeera.com

11 See gisreportsonline.com

12 See thearcticinstitute.org

13 See macdonaldlaurier.ca

14 See international.gc.ca

15 See epaper.nationalpost.com

16 See macdonaldlaurier.ca

17 See arcticwwf.org

18 See thebarentsobserver.com

19 See businessindexnorth.com

20 See thearcticinstitute.org

21 See specialeurasia.com

22 See specialeurasia.com

23 See aljazeera.com

24 See warontherocks.com

25 See worldwildlife.org

26 See thearcticinstitute.org

27 See mine.nridigital.com

28 See arcticeconomiccouncil.com

29 See arcticwwf.org

30 See containerlift.co.uk

31 See economist.com

32 See climatetrace.org

33 See sciencedaily.com

34 See foreignpolicy.com