June 2020

Over the past four decades, corporate tax rates have been on a downward trajectory. Graham Buck examines why 2020 could mark a watershed when that trend starts to reverse

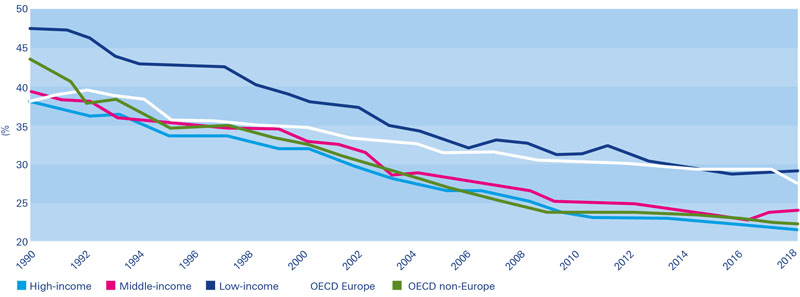

Those of the baby boomer and Generation X eras might remember 'The Only Way Is Up', a strident anthem from the late 1980s by the singer Yazz. It reflected hedonistic times when the price of everything from property to works of art such as Van Gogh’s Sunflowers was heading steadily higher. One notable exception was corporate tax rates, which were already heading in the opposite direction. ‘The Only Way is Down’ more appropriately describes their trajectory over the past four decades. In September 2019, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) reported in Tackling Tax Havens that average corporate global tax rates have halved since 1985, from 49% to 24%.1

Contributing to the decrease was the introduction of the US Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) in 2017. Signed by US President Donald Trump three days before Christmas, it reduced the US corporate tax rate from 35% to 21%.

However, the TCJA might prove to be the last shout, as increasingly the steady downward trend in corporate tax rates shows signs of halting – and even reversing. When campaigning for re-election in November 2019, UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson announced that planned cuts to the UK corporate tax rate from 19% to 17% in early 2020 had been put on hold and the estimated £6bn cost would instead be diverted to “national priorities”, such as the health service.

In January 2020, an open letter from more than 120 wealthy individuals spanning celebrities to business leaders lamented a “precipitous” decline in tax receipts from both corporations and the ultra-rich, fuelled by tax avoidance reaching “epidemic proportions”.2

Advocating international tax reform and releasing their letter to coincide with the World Economic Forum (WEF) in Davos, the group dubbed themselves the Patriotic Millionaires and cited a 2018 IMF report that found US$12trn of investment by multinationals is “completely artificial” and resides in empty corporate shells around the globe. This had contributed to “extreme, destabilising inequality” and the resulting tensions had reached crisis point, according to the letter. “Low social trust and a pervasive sense of unfairness are diminishing basic social cohesion,” the group warned.

Drivers for change

A pre-Covid-19 report by Jim Reid and Luke Templeman of Deutsche Bank Research, 2020: An Inflection Point in Global Corporate Tax?, 3 suggests that this could be the year that marks a watershed, when the drive towards global tax coordination starts to gain traction. Reid and Templeman note the following:

- State finances are precarious, yet companies are in great shape thanks to the steady decline in corporate tax rates. Prominent US and European politicians have made higher corporate taxes over the medium term a key part of their election platforms.

- More than 100 countries are working on the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD’s) proposals for a globally coordinated model of corporate taxation. In future, corporates may have to pay tax in each country where they have sales, regardless of the level of activity on the ground, and minimum tax rates may has changed. The new focus on where apply. The OECD issued a more specific set of guidelines at the end of January 2020 in response to feedback.

- To prepare for higher taxes in the medium term, corporates should consider their strategies around decentralisation, capital expenditure, mergers and acquisitions, and changing performance metrics to prioritise return on assets.

There has been a definite shift in mood, agrees Graham Robinson, Leader of PwC UK’s Finance and Treasury Tax specialist team and a qualified treasurer who acts as an adviser to the Association of Corporate Treasurers (ACT). “Territories now want to collect tax and don’t want revenues disappearing,” he adds. “Straightforward tax rate cuts for business are increasingly hard to justify.”

According to Robinson, the OECD, the G20 and their combined Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) project all maintain that corporates shouldn’t be avoiding their responsibility to pay tax via re-domiciling or restructuring, and that they should pay tax in the locations where they conduct their business.

He explains that this is currently a particular issue with the big internet/platform companies; hence the plans by the UK government to levy a digital tax. This is likely to be a precursor to a wider international initiative on profits of internet-based business models. It also points to greater revenue-raising efforts by governments in the years ahead.

"The new focus on where the organisation’s management teams and main offices are located changes the dynamics by which corporate treasury needs to operate"

Figure 1: Race to the bottom: corporate income tax rates have fallen significantly over the past three decades

(figure shows combined corporate income tax rates by country group, in percent)

Source: IMF, Global Financial Data, Deutsche Bank

Winners and losers

24%

Many commentators suggest that as reallocating taxes will involve gains by some countries at the expense of others, efforts to implement globally coordinated tax policies and a common tax regime will be thwarted. However, Reid and Templeman believe this view is overly pessimistic for three reasons:

- The new tax regime won’t necessarily be a “zero-sum game”; some companies will simply need to dig deeper and many larger countries stand to benefit.

- Low-tax countries that stand to lose tax revenue may find that resistance is futile if larger, richer countries lend the initiative their support. Some of the companies that stand to be impacted by the change nonetheless support it and Amazon has called the initiative “an important step forward”.

- The new regime will ease competitive pressures on countries to reduce their corporate tax rates. As profits will be taxed in the country where its business activity takes place, the location of a company’s headquarters or legal domicile should no longer matter.

“One effect of BEPS has been to manage the exploitation of low-tax territories and stipulate that taxable profits reflect actual substance, which means the location where the company pays tax is also one where it has a significant presence and people who are its decision takers,” says Robinson. This is because it has reduced the extent to which taxable profit can be avoided by corporates by having a token presence – such as a couple of individuals – located in a low-tax territory.

As a result, the model for companies using locations such as Ireland and Luxembourg as effective vehicles for managing tax the ground, and minimum tax rates may has changed. The new focus on where the organisation’s management teams and main offices are located puts a much greater emphasis than before on the location of the treasury function.

“It raises the question of whether companies that have set up a light-touch operation in a location such as the Cayman Islands need to increase their local staffing levels or migrate their activities to other locations,” reflects Robinson. “They certainly need to reassess such operations following the introduction of these local ‘substance’ requirements that need to be met. Any organisation that fails to do so faces extra tax bills globally, and the risk of fines or other penalties in the low-tax territory.”

Naresh Aggarwal, Associate Director Policy & Technical for the ACT, points out that for many treasurers implementing the necessary outcomes can require significant effort. Key actions can include restructuring existing internal and external funding arrangements, talking with investors, managing any associated derivatives (including those whose hedge effectiveness may be affected), and changes to internal and external reporting. Additional considerations will include access to appropriately skilled staff who can support the various treasury activities.

The Cayman Islands – companies may need to rethink light-touch operations in the territory

Taxing digital

The follow-ups to BEPS, Pillar One and Pillar Two focus on a global minimum tax for business, with particular attention devoted to the digital economy and those active in online business that may not necessarily have a formal company presence. Again, the issue is taxing the profits accruing from transactions in the location where the company’s decision makers are situated.

Given that one of the direct implications for treasury is the need to decide where the organisation’s treasury centre and its funding vehicle is located, a Londonbased online company that deals with a large number of users in another country could have a taxable presence in that non-UK location. It would then need to comply with local tax laws and make local tax payments.

The success of platform businesses such as Facebook and Uber, which have multiple customers, has also raised further questions regarding the application of a digital tax. “The concept is that the company has a taxable presence, through the many users of its service who are creating value,” says Robinson. “At the same time, it’s fairly nebulous and hard to define – particularly for online marketplaces or online gambling. The question is, at what point do such operations become taxable? There’s still no unanimity between countries on the issue, as a variety of differing interests reflect their particular economic base.”

Robinson explains that the US opposes any digital tax, which it regards as an opportunity by other territories to take away money for US operations. This sensitivity was evident in January 2020, when France backtracked on plans to levy a 3% digital services tax on the annual revenue generated by major digital companies in providing services to French users. Claiming that the tax was aimed solely at its tech giants, the US threatened retaliatory tariffs on French goods.

“At the same time, the UK and the EU all want to see the introduction of a consistent system that ensures harmonisation, so that multinationals no longer take advantage of low-tax territories to accrue profits,” Robinson reflects.

"Taxes are the best and only appropriate way to ensure adequate investment in the things our societies need"

January 2020 letter to the WEF from the Patriotic Millionaires

Targeted incentives

The US corporate tax cuts in 2018,4 which brought the US in line with other territories, also lessened the incentive for multinational corporations (MNCs) to move profit out of the US to an overseas location. While the rate was reduced, the corporate tax base was broadened and a new rule introduced the sweeping up of any unrepatriated profits of MNCs, while dividends were made tax-exempt. Under the global intangible low-taxed income regulations, aka the GILTI rules, unrepatriated profits are taxed as they accrue.

Robinson says the future of corporate tax in the UK is currently up in the air, as the country finally exiting the EU at the end of January has not removed many of the uncertainties created by Brexit. As with other areas of law, there is a tension between the benefits of alignment with the EU and the suggestion that the UK should create its own laws. In tax terms, this applies to questions such as the extent to which the tax system can offer incentives without this being ‘state aid’, and whether the UK should follow EU-driven anti-avoidance initiatives.

“There’s a wish for the UK to continue to be an attractive investment location, so the government can be expected to continue along that path,” Robinson adds. “However, the big headline-grabbing tax rate cuts are likely to be replaced by more targeted incentives and a flexing of the corporate tax base. There are already incentives to attract research and development.”

Further ahead

Another issue to be addressed in the 2020s is whether new forms of taxation will either be added to or replace old ones. For example, will tax regimes be used to ensure that the growing use of robots is matched by the retraining of those directly impacted? “An evolving tax regime will reflect where value is added, although quite what a ‘robot tax’ would look like has yet to be clarified,” Robinson says. “This regime will very likely include a rise in indirect taxes, including sales tax, VAT, financial transactions tax and stamp duty, which are all easier to identify and value.”

As Aggarwal notes, further challenges are likely to arise from the rapid growth of realtime payments and growth in the associated payment data. Tax authorities are looking at opportunities to reduce any tax leakages, and this includes the potential for expecting taxes to be paid across to the authorities at the point of sale. With connectivity between various companies increasing all the time, the real-time collection of tax on transactions and continuous visibility of tax liabilities will have a significant impact on cash management activities.

“The UK government’s Making Tax Digital initiative5 makes the e-filing of VAT mandatory,” Robinson says. “What has happened in some countries such as Brazil – although not yet the UK – has been direct systems access between the tax authorities and the taxpayer.

“We can also expect greater coordination between territories and the increased use of profiling and analytics to access taxpayer behaviour. More automation will extend from routine compliance functions to others; for example, using analysis in deciding which tax returns should be subject to enquiry.”

Finally, a further corporate tax-related issue of specific interest to treasury arises from the premise that the tax applicable to a corporate should reflect where its main people and functions are located. This, suggests Robinson, is steadily being blurred by the increasing mobility of key individuals within an organisation, who may move between locations regularly or work from home. So there will be more questioning of the “taxable presence”, and when a key individual regularly travels abroad the issue will arise of just where the taxable presence is created.

Sources

1 See https://bit.ly/2xbomkH at imf.org

2 See https://cnb.cx/32Q1t1P at cnbc.com

3 See https://bit.ly/32OSqyh at dbresearch.com

4 See https://bbc.in/2XljwLp at bbc.com

5 See https://bit.ly/2VQQzY6 at gov.uk

You might be interested in

REGULATION, CASH MANAGEMENT

Covid-19: Financial regulatory responses Covid-19: Financial regulatory responses

As sectors across the economy attempt to bolster their resilience against the Covid-19 pandemic, regulators have been playing their part in keeping the wheels turning

CASH MANAGEMENT

Basel yesterday, today and tomorrow Basel yesterday, today and tomorrow

Prudential regulation in the form of the Basel accords on capital adequacy has been evolving for almost 30 years. Etay Katz and Kirsty Taylor explain this quest for safety and soundness as “Basel IV” awaits agreement

Sustainable finance

Eight ESG trends to watch in 2024 Eight ESG trends to watch in 2024

What is next for ESG in 2024? From the greater focus on the impact and execution of sustainability targets, to new geopolitical and regulatory priorities, flow explores eight key sustainability themes that corporates should watch out for