29 November 2024

Marked by tough negotiations, COP29 closed with agreement to triple finance to developing countries by 2035 and a long-awaited breakthrough on international carbon markets. Yet not all expectations were met. flow’s Desirée Buchholz summarises the key takeaways from Baku

MINUTES min read

The political climate for this year’s UN Climate Change Conference in Baku, Azerbaijan – also known as COP29 – was testing. Several key European leaders such as French President Emmanuel Macron, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz and Ursula von der Leyen, President of the EU Commission, skipped COP29 for different reasons, while US President-Elect Donald Trump is widely expected to pull the United States out of the Paris climate agreement again, as he did during his first term.1

“The event now serves as a forum to discuss how to tackle climate change without the support of the US, which is estimated to contribute around 13% of annual global carbon emissions,” wrote Debbie Jones, Global Head Sustainability and Data Innovation, Deutsche Bank Research in her pre-COP assessment What to expect at COP29 in Baku published on 11 November, the conference’s opening.

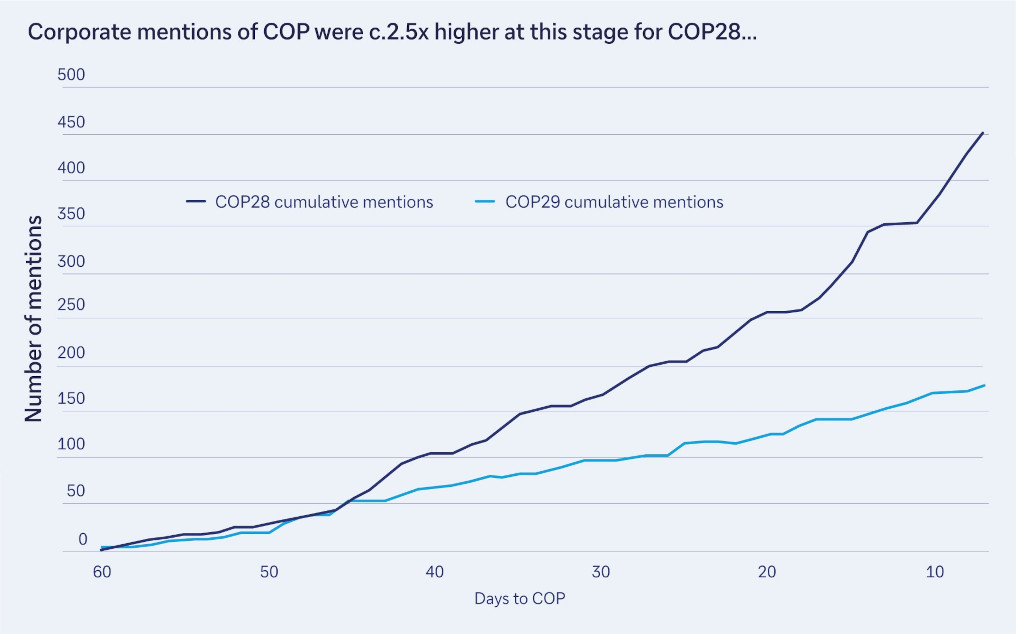

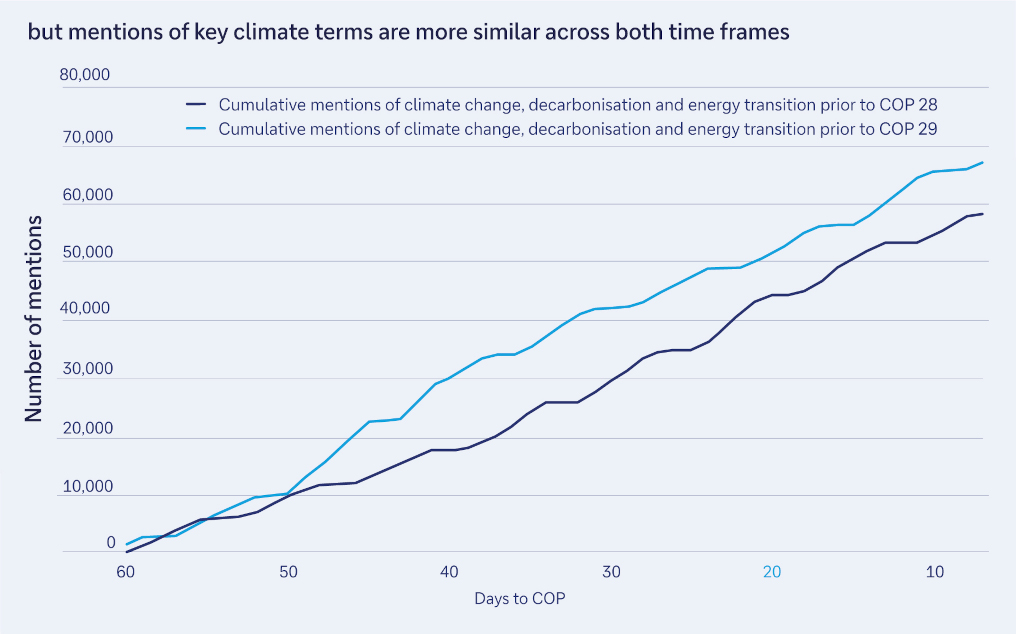

At the same time, business leaders did not rank the 2024 conference as highly as in previous years, the report found. Figures 1 shows that COP mentions by corporates were lower in the run-up to the conference on a relative year-to-year basis. Yet, this is not the case for key climate related terms such as climate change, decarbonisation, and energy transition (Figure 2) – suggesting that it is not the topic of climate change but rather the format of COP that ranks lower on business leaders’ agendas.

Source: Deutsche Bank Research report What to expect at COP29 in Baku

Despite these headwinds, COP remains an important global platform to jointly address the challenges of climate and nature and to develop solutions – with Baku attracting delegates from nearly 200 countries. “Government representatives are very clear by now that it takes banks and industrial companies to bring the transformation to life. They want to know what really works – and what doesn’t. That’s why the exchange at COP is so important,” commented Jörg Eigendorf, Chief Sustainability Officer at Deutsche Bank while attending the conference.

“Government representatives (…) want to know what really works – and what doesn’t. That’s why the exchange at COP is so important”

So, what were the concrete outcomes this year? This article summarises the four key takeaways from the conference – focusing on areas where progress has been made and where more work is needed at next year’s COP30 at Belém, in the heart of Brazil’s Amazon.

1. New climate finance goal established

Long before COP29 kicked off, it was clear that climate finance would be this year’s key focus – institutions such as the World Economic Forum had even dubbed the event the “Finance COP”, seeing it as an opportunity to align climate finance contributions with estimated global needs2. Last year’s COP28 in Dubai calculated that developing countries will need US$215–387bn annually up until 2030 for adaption measures alone.3

Yet negotiations were tough and prolonged, given the gulf between the expectations of contributing and recipient countries: Not until the early hours on Sunday, 23 November did all parties agree to triple annual finance to developing countries from the current US$100bn to US$300bn by 2035.

The figure still falls well short of US$1.3trn public spending in the form of grants rather than loans annually that poorer countries had demanded to ensure investment in clean energy and adaption to climate change. The final agreement includes a weaker “call on all actors to work together to enable the scaling up of financing to developing country parties for climate action from all public and private sources to at least US$1.3tn per year by 2035” – emphasising once again the importance of mobilising private capital.

“To accelerate growth and scale private-capital flows, we need to step-up discussions, and focus on the business case”

On the other hand, developed countries unsuccessfully attempted to convince some of the excluded countries – namely China and countries in the Middle East – to be re-classified as contributors to reflect changes in the global economic landscape. Currently, contributors to the financing target are still defined as the 24 countries who were OECD members when the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) was signed in 1992. The final deal now “encourages” developing countries to make contributions on a voluntary basis.

“This new finance goal is an insurance policy for humanity, amid worsening climate impacts hitting every country,” commented Simon Stiell, Executive Secretary of UNFCCC, on the agreement. “But like any insurance policy, it only works if premiums are paid in full, and on time. Promises must be kept, to protect billions of lives,” he warned.

In the first week of the conference, 11 multilateral development banks (MDBs) announced that their annual collective climate financing for low- and middle-income countries will reach US$120bn by 2030, of which US$42bn are earmarked for extreme weather adaptation measures, with US$65bn to be mobilised from the private sector.4

“To accelerate growth and scale private-capital flows, we need to step-up discussions, and focus on the business case”, comments Lavinia Bauerochse, Global Head of ESG, Deutsche Bank Corporate Bank. “The green transition needs to be economically viable. From a corporate perspective, it’s about transitioning business models into a sustainable future to prepare for inherent risks but also capture the opportunities.“

2. Breakthrough on carbon markets

Another top priority for COP29 was to reach an agreement on carbon markets – a goal which several previous COPs had failed to achieve. Carbon markets put a price on emitting greenhouse gases (GHG) thereby incentivising countries and companies to reduce emissions, as described in the flow article The price of CO2. Moreover, they help to steer capital to where it can be most efficiently used to invest in clean energy, or conserve carbon stocks in ecosystems such as a forest.

This ambition also identified by the 2015 Paris Agreement Article 6 International Transfer Mitigation Outcomes (ITMOs), which allow countries to transfer carbon credits produced through the reduction of GHG emissions to help other countries meet their climate goals. In 2022, the World Bank estimated that such an international carbon credit transfer system could slash the cost of implementing countries’ emissions reductions plans — so-called Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) — by over half, or as much as US$250bn in 2030.5

“The achievements on carbon markets stand out as some of the most notable from this year's event”

After nearly a decade of work, nations attending COP29 have now agreed on the final building blocks that set out how carbon markets will operate under the Paris Agreement, making country-to-country trading and a carbon crediting mechanism fully operational. According to the UNFCCC, the decision made in Baku now provides clarity on how countries will authorise the trade of carbon credits and how registries tracking this will operate (Article 6.2). “And there is now reassurance that environmental integrity will be ensured up front through technical reviews in a transparent process,” the UNFCCC writes.6

Over the past two years, voluntary carbon markets have come under pressure, reflecting concerns around the actual climate benefits of projects qualifying for carbon offsetting. To make the market more transparent, comparable, and credible, the Integrity Council on Voluntary Carbon Markets – a multi-stakeholder led independent governance body – had in March 2023 launched its “Core Carbon Principles” (CCPs) – a set of ten principles defining high-quality credits with a focus on governance, emissions impact, and sustainable development in March 2023. While this was considered a good starting point in bringing integrity into voluntary carbon markets, it could not replace a mandatory agreement of carbon credits under Article 6.

As COP29 began, countries had already agreed standards for a centralised carbon market under the UN (Article 6.4 mechanism). “These achievements stand out as some of the most notable from this year's event. While this will not receive the same media attention as the climate financing agreement, it is important not to understate the importance of these agreements, particularly for developing nations, who often have ecosystems well suited to carbon credit trading,” Debbie Jones from Deutsche Bank Research wrote in her 27 November Special Report COP29 – Top 10 takeaways.

3. First countries have introduced more ambitious climate goals

COP29 also delivered previews for the national climate action plans which countries must submit to the UN every five years according to the Paris Agreement. The next round of these NDCs is due by February 2025.

During his speech in Baku, UK Prime Minister Keir Starmer pledged that the country would cut emissions by 81% from 1990 levels by 2035. To date, the UK has roughly halved its emissions compared to this baseline. Since coming into office on 5 July 2024, his government has legislated to abolish the ban on onshore wind, committed to not issue any further oil and gas licences within the North Sea and become the first G7 country to abandon coal power, Starmer added.7

The United Arab Emirates (UAE) – the host of last year’s COP28 – announced that it plans to reduce its GHG emissions from 2019 levels by 47% by 2035. Most of the cuts are targeted to come from buildings (-79%), followed by agriculture (-39%), waste (-37%), industry (-27%) and transport (-20%).8

Brazil –– the host of next year’s COP30 –– has pledged to reduce its CO₂ emissions by 59% to 67% by 2035 compared to 2005 levels. Brazil’s NDC also outlined efforts to phase out fossil fuels across sectors through its national energy policy, although it omits explicit targets and clear timelines. The goals also demonstrate a strong commitment to achieve zero deforestation and plans for large-scale restoration of native vegetation.9

4. More work needed on energy transition and grid expansion

On the downside, COP29 failed to reaffirm the previous year's commitment to transition away from fossil fuels. The final agreement at COP28 also included a pledge to triple renewable energy capacity by 2030.10

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), combined investment in renewable power and grids overtook the amount spent on fossil fuels for the first time in 2023. For 2024, the IEA expects global clean energy investment to exceed US$2trn.11 Yet, grid and storage infrastructure was identified as a key limiting factor impeding the energy transition.

This is why COP29 Presidency Azerbaijan launched a Global Energy Storage and Grids Pledge, seeking country endorsements to increase global energy storage capacity to 1,500 gigawatts by 2030. This would be a six-fold increase from 2022. The pledge also aims to scale up investments in electricity grids, “in line with IEA’s analysis that annual global investment in grid infrastructure (both transmission and distribution) needs to reach US$600bn by 2030”.12 Parties endorsing this pledge included the US, the UK, Germany, Brazil, the UAE, and Saudi Arabia.13

Additionally, 25 countries including the UK, Canada, France, Germany and major coal producer Australia committed to building no new coal-fired power plants. They also called on “all countries to end new coal power in the lead up” to next year’s COP30 – a very ambitious diplomatic initiative given that in China, 47.4GW of coal power capacity came online in 2023 and 32 other countries have new coal projects at pre-construction phases of development.14

Looking ahead to Brazil 2030

Attention is now turning to COP30 which will take place during November 2025 in Belém, Brazil. It is expected that energy transition will be back in focus under Brazilian leadership. Moreover, given that Brazil hosts between 15 and 20% of the world’s biological diversity15, the Brazilian government has also stated it will focus on the role of nature for fighting climate change.16

Currently, about 50% of emissions are absorbed by nature, such as forests or wetlands, and the oceans. However, this ability to capture carbon decreases because of environmental destruction.17 As Deutsche Bank’s Eigendorf commented, “We need to give nature a value. Quickly. Only when governments, companies and banks succeed in better integrating the costs of doing business into our global pricing system, thereby creating the right incentives, we will be successful in the fight against climate change.” How that might be achieved will shape the discussions in Belém.

Sources

1 See politico.eu

2 See weforum.org

3 See COP28 – key takeaways from Dubai

4 See worldbank.org

5 See worldbank.org

6 See unfccc.int

7 See gov.uk

8 See enerdata.net

9 See unfccc.int

10 See COP28 – key takeaways from Dubai

11 See iea.org

12 See cop29.az

13 See argusmedia.com

14 See carbonbrief.org

15 See unep.org

16 See nature4climate.org

17 See weforum.org