June 2018

How can China maintain the war on smog yet ensure steady supplies of home-produced aluminium? flow’s Clarissa Dann investigates how prepayment finance supported Qiya in honing its low-cost, reduced-emissions technology

Winter in Beijing looks very different now that state-mandated factory closures and policies to protect the environment have begun to take effect.

“I was going into our offices with my colleague who was over from Frankfurt, and he remarked on the clear blue skies,” says Deutsche Bank’s Regional Head of Structured Commodity Trade Finance (SCTF), Asia Pacific, Frank Wu. His colleague was in good company: the French President, Emmanuel Macron, had made a similar observation on a state visit early in 2018. “I’ve never seen Beijing like this,” he said, commenting on the Chinese government’s action to close its factories. He added, “It shows they have a capacity that is rapid, even brutal.”1

Blue-sky blues

The city has been plagued with air pollution problems that become more pronounced with the arrival of colder weather. Demand for heating rises, coal-fired power plants ramp up their production and the particle-filled warm emissions from surrounding factories get trapped beneath the cold air, unable to disperse. Something had to be done, and done quickly.

China’s industrial revolution may have catapulted it to the top spot in purchasing power parity GDP (US$22trn according to the World Bank), but this has come at a price. The coal that powers China’s factories and manufacturing plants pushes out air pollution estimated to kill 1.1 million people a year.2

This does not sit comfortably with President Xi Jinping’s vision of a “Beautiful China” outlined at the start of the 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China on 18 October 2017. He stressed that China had to pursue a model of sustainable development, featuring increased productivity, higher living standards and healthy ecosystems. “The modernisation that we pursue is one characterised by harmonious co-existence between man and nature,” said President Xi to more than 2,300 delegates and guests.

"SCTF makes it possible to do business in a way that is resilient through commodity cycles"

In one fell swoop, the government has put into place its anti-pollution measures, which include enforced reductions in output from factories in the areas surrounding the capital city. The approach is rather different from Western Europe. Jack Pease, Editor of Air Quality Bulletin, tells flow, "The UK government's response to the growing problem of wood smoke in London due to spiralling numbers of fashionable new wood burners is to issue a leaflet. In China, during pollution peaks, temporary bans on polluting processes and vehicles are mandated, almost overnight."3

According to energy consultancy Wood Mackenzie, in the 2+26 catchment area around Beijing, air pollution control measures in place from mid-November to mid-March have led to a 30% cut in aluminium output and another 30% cut in alumina output.4

So how is China going to have its fortune cookie and eat it? Infrastructure investment into One Belt One Road initiatives assumes that aluminium and steel – and plenty of it – will be available. In addition, energy cost can represent up to 30% of metals production costs, as in the case of aluminium – and the winners in this more enlightened climate of cleaner manufacturing are smelters that do not have to transport their coal long distances from pit to plant and that find ways of using less of the shiny black stuff.

Having told the story of Fangyuan Group and how it had developed a technology for smelting copper with a reduced environmental impact in Issue 4 of flow, this article turns to the Xinijang Qiya Aluminium and Power Company (Qiya) and how pre-delivery finance has helped it navigate a challenging business cycle and trading environment – and win a GTR Deals of 2017 industry award.

Light and shiny

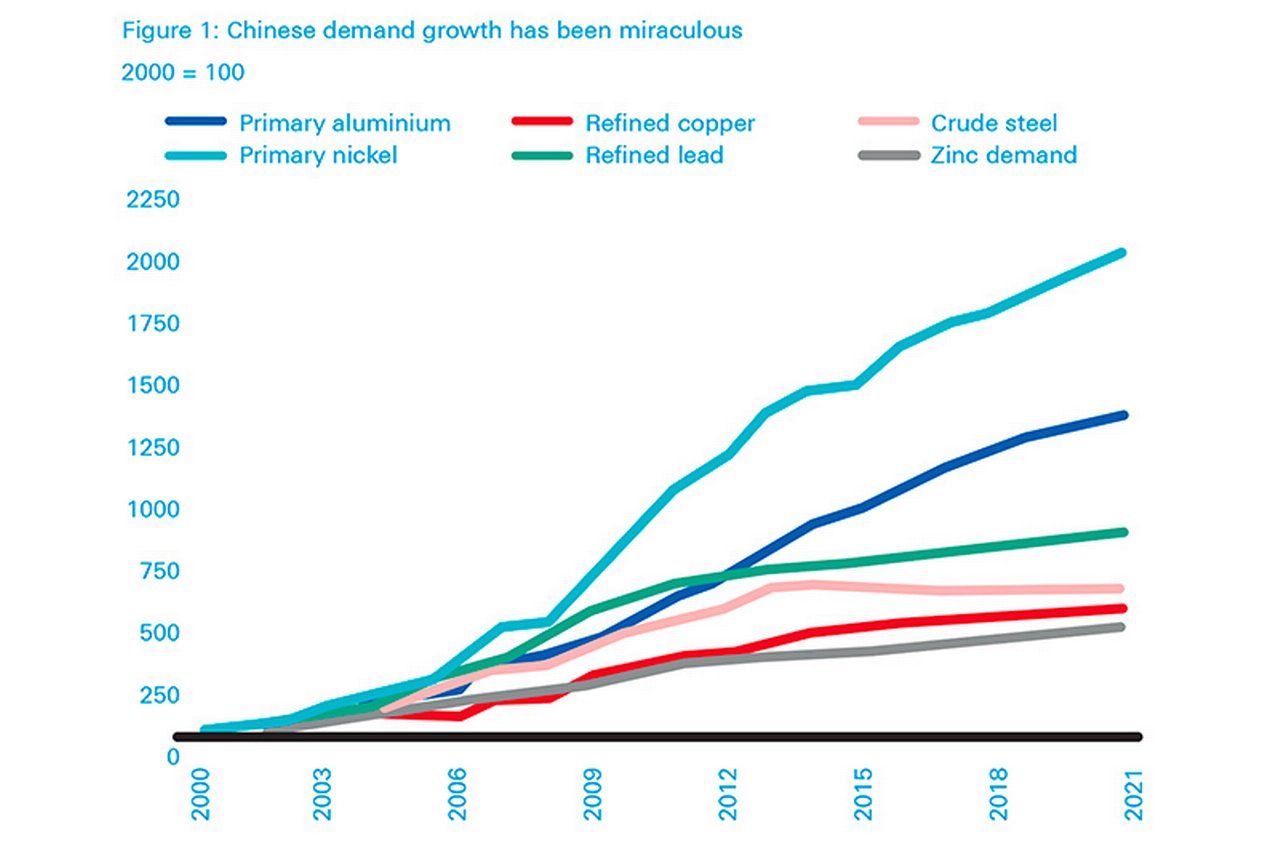

Aluminium touches most aspects of everyday life, and is used in products including cans, foils, kitchen utensils, window frames and aviation components. Chinese metals demand growth has been significant compared with that of the rest of the world since 2000. The country has evolved along its economic growth pattern from a rural and agricultural economy, to urban and industrial. Most recently, China has become an urban and service economy.

Aluminium is also found in electric vehicles (EVs) – and there were around two million in 2016, according to the International Energy Agency. China plays a dominant role in the EV market, accounting for 30% of total car sales and half of electric car sales. Chinese EV manufacturer BYD operates out of Shenzhen and is the world’s largest maker of electric cars. Tesla may have more global recognition, but BYD’s focus on the transportation market, in addition to passenger vehicles, has helped to fuel its rapid growth. As China continues to diversify and upgrade its automotive and aerospace industries, this creates consistent demand for aluminium. No surprise, then, that the largest production of aluminium in the world takes place in China, with 31 million metric tonnes produced in 2016. Russia is second at 3.580 million metric tonnes.5

31 million

Although it is the most abundant metal in the earth’s crust, aluminium has to be extracted from compounds – the dominant one being bauxite. Australia and China are among the world’s top processors, with Indonesia, Guinea, Australia and Vietnam leading the pack for bauxite reserves. Once mined, the ore is chemically extracted and refined into alumina, an aluminium oxide compound, and then smelted into aluminium metal. Alumina refining and aluminium smelting will sometimes be found in the same businesses (such as Qiya), but not always.

Silk Road gateway

Qiya, the core aluminium production division of the Sichuan Qiya Aluminium and Power Company, was established in 2011 and is located in Wucaiwan, north of Urumqi, the capital city of Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (Xinjiang) in northwest China.

Conveniently, the production facilities sit at the gateway to the Silk Road, where aluminium can be exported west into Kazakhstan and out into other Central Asian countries. While the war on smog has resulted in curtailment of coal production in many provinces, Xinjiang is least affected. The autonomous region’s massive coal reserves (estimated at around 38% of the national total of around 115 billion metric tonnes), vast land area at 1.6 million km2 (it is almost three times the size of France), low population density, and great distance from China’s developed coastal regions make it the ideal location to convert coal into energy, and ultimately into aluminium ingots that can be shipped all over the country.

Sustained investment in modern power generation and smelting technology, and access to cheap but high-quality local coal resources, have made it possible for Qiya to become one of the lowest-cost vertically integrated aluminium smelters in the world – the choice of location pretty much determines 95% of the cost structure. None of the infrastructure is more than three years old, and instead of coal being transported to the works at considerable freight cost and environmental impact, it comes from nearby open cast mines within 10km. These can be transported entirely via a conveyor belt system that minimises weight loss and diffusion of particles along the way. “If you have to ship or truck the coal, your cost will go up,” says Frank Wu. He adds, “Aluminium can be seen as ‘packaged electricity’ – that is why producers move to regions rich in coal resources, and this also helps the local economies.”

The holding company, Sichuan Qiya Aluminium and Power Company, was founded in 1989 by Tong Wenqi and is headquartered in the Emeishan City of Sichuan Province. It entered the aluminium industry in 1995 and ventured upstream into alumina production in 2009 to be further vertically integrated. The group now owns around 800,000 tonnes per year of aluminium smelting capacity and 1.2 million tonnes per year of alumina refining capacity.

Financing growth

While Qiya has enjoyed the support of Chinese financial institutions on a bilateral basis, it needed to look for new sources of finance once most of its fixed assets had been pledged to cover existing facilities. Commodity trader Trafigura sources commodities where they are plentiful and supplies them to where they are needed. As its Head of Structured and Trade Finance, Stephan Jansma tells flow, “Qiya is a prime example of this. We supply the alumina and off-take the aluminium for distribution throughout China. We had identified Qiya as a key partner due to its strategic location and low production costs.”

Trafigura has maintained a commercial relationship with Qiya since 2015 and has provided prepayments to it since 2016. “After gaining positive experience, it was logical for us to introduce some of our key relationship banks in China, of which Deutsche Bank is one,” reflects Jansma. In this deal, the ingots would be delivered from Wucaiwan to coastal China locations and further distributed by Trafigura’s onshore trading subsidiary to the downstream consumers.

"We are confident that the partnership with Deutsche Bank and Qiya will expand in the coming years"

On 3 November 2017, Qiya signed an RMB600m (US$90.65m) pre-delivery financing with Deutsche Bank and Rabobank, without pledging any more fixed assets. This was the first time that Qiya had come into a club deal run by international banks, and it was an important line in the sand to demonstrate that this corporate’s business and risk profile could be accepted by them. “Once the door is opened, more banks will come and more repeat deals will follow,” predicts Wu, who sees it as a personal mission to develop new clients rather than being a follower. Jansma agrees. “We are confident that the partnership with Deutsche Bank and Qiya will expand in the coming years, providing more and longer dated prepayments, with a reduced risk participation by Trafigura, now that the banks have gained experience as well,” he concludes.

The comfort for the lender here is that the facility is self-liquidating. The cash flow from aluminium sales from Qiya to Trafigura goes through the lender’s controlled collection account, and is applied directly for debt servicing. Such pre-delivery finance structure has been used in China by the SCTF team since 2010, with flawless track records.

A tight security package consists of a pledge of all the borrower’s receivables under the off-take contract with Trafigura, a pledge over the cash deposit in the collection account, a corporate guarantee from the holding company, a personal guarantee from the founder and owner, Tong Wenqi, a 15% risk sharing, and an off-take payment guarantee from Trafigura.

Another key factor in this deal was currency. The Chinese government is not only trying to clean up pollution, but also to reduce the debt mountain. Monetary supply was tight in 2017, and Chinese private sector metals corporates were finding it tough to borrow onshore in RMB and were more willing to explore offshore dollar funding. On top of this, the RMB strengthened against the dollar in 2017, making the dollar even more attractive.

Supply and demand

At the time the deal was signed, aluminium prices had risen, according to the London Metals Exchange, from the H1 2016 low of just under US$1,543/tonne to around US$2,100/tonne. Supply-side Chinese reform has generated positive spill-over effects now that the emphasis is no longer on building as much capacity as possible. Positive externality (the focus on efficiency and cost reduction) has benefited rest of world aluminium producers such as Russia’s Rusal. The world’s second largest aluminium producer reported improved Q2 2017 EBITDA as a result of its efficiency and cost reduction measures.6

Commodity price volatility should not affect well-established banking relationships. The whole point of the SCTF business model, says Wu, is that it “makes it possible to do business in a way that is resilient through commodity cycles.” Wu continues, “That means when prices go up, we don’t get over-excited and lend out money without discretion. Equally, when the prices come down, we don’t panic and pull credit lines from our clients. Instead, we focus on identifying companies with long-term sustainable competitive edges (such as achieving low cost through technology), because these companies won’t be affected by the ups and downs of commodity prices.”

The focus on clean production and efficiency looks set to continue. Of course, this does mean that the occasional visibility of Beijing’s landmarks, such as the Forbidden City and the China Central Television Building, against a backdrop of clear blue skies will no longer have rarity value, but this can only be a good thing.

Sources

1 As reported in http://www.ft.com/, 11 January 2018 at ft.com

2 See https://bit.ly/2il4Jvd at nationalgeographic.com

3 See www.empublishing.co.uk at empublishing.co.uk

4 See www.woodmac.com at woodmac.com

5 See https://on.doi.gov/2um0CbQ at usgs.gov

6 See https://rusal.ru/ at rusal.ru

Frank Wu

Regional Head of Structured Commodity Trade Finance, Asia Pacific | Deutsche Bank

Stephan Jansma

Head of Structured and Trade Finance | Trafigura

Go to Corporate Bank EXPLORE MORE

Find out more about products and services

Go to Corporate Bank Go to Corporate BankStay up-to-date with

Sign-up flow newsbites

Choose your preferred banking topics and we will send you updated emails based on your selection

Sign-up Sign-upYou might be interested in

Trade finance and lending

RCEP launches after eight years’ gestation RCEP launches after eight years’ gestation

Fifteen Asia-Pacific economies sign up to the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) Agreement in a move back towards multilateral trade and tariff reduction. flow's Clarissa Dann summarises what this means for trade

Trade finance and lending

A new philosophy for re-building global trade A new philosophy for re-building global trade

Global value chains play a central role in the functioning of the global economy – fostering job creation, prosperity, innovation and investment. But how can they meet the challenges of a post-pandemic world? flow reports from the ICC International Trade and Prosperity Week

Trade finance and lending {icon-book}

Call for capacity Call for capacity

Trade finance shortages remain a barrier to developing world economic growth, as the gap between the perception and actual level of transaction risk widens. Tackling this is an ongoing priority, says the WTO’s Marc Auboin