September 2020

As corporates revisit their supply chain exposures as a result of Covid-19, could just in time supply chains be replaced by planning ‘just in case’? Treasury specialist Helen Sanders reports on business continuity management strategies

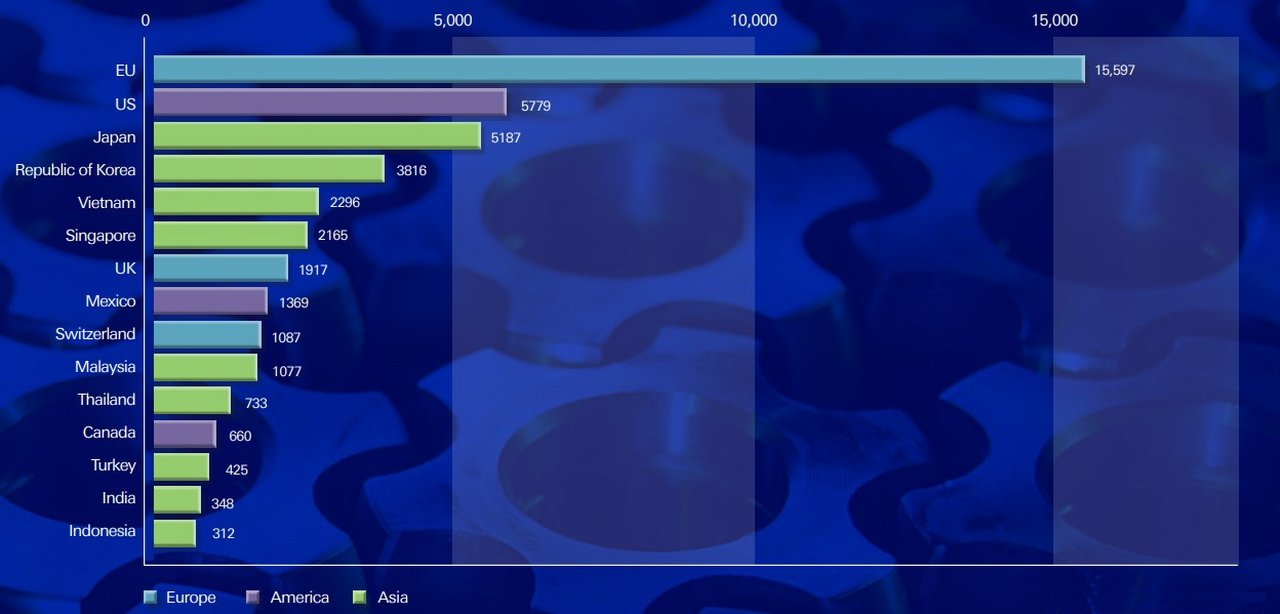

The slowdown of manufacturing in China due to the Covid-19 outbreak is disrupting world trade and could result in a US$50bn decrease in exports across global value chains, according to estimates published by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) on 4 March.1 Europe has been particularly affected (see Figure 1 below), causing many companies to question not just the apparent lack of diversification and resilience in their supply chains, but also the speed with which the pandemic affected or even paralysed supply chains, particularly in the precision instruments, machinery, automotive and communication equipment sectors.

This article takes a closer look at how businesses have been tackling supply chain-related business continuity issues during the immediate crisis period and attempts to understand what the experiences of the pandemic could mean for supply chain planning in future.

Figure 1: Trade impact of the Covid-19 epidemic (US$m), top 15 most affected economies

Source: UNCTAD estimates**Estimates are based on a drop of Chinese supply in February 2020, as measured by the Chinese PMI.

This list does not include Taiwan Province of China and Hong Kong, SAR of China

Has just in time (JIT) manufacturing failed?

Companies in many industries, particularly automotive, manufacturing and technology, have embraced JIT supply chains to reduce working capital tied up in inventory, and to flex production in line with changing customer demand.

On 10 March 2020, the day the first European lockdown was imposed in Italy, nearly 75% of respondents to an Institute for Supply Management survey reported disruption to their supply chains.2 Lead times more than doubled from December on average, with 62% experiencing order delays and over half struggling to communicate with supply chain partners in China. A month later, a second survey reported that more than 95% of respondents expected supply chain disruption.3

As every region in the world gradually locked down, the effects of disruption to both production and customer demand were exacerbated. Increasingly, the nature of global supply chains came into question. In particular, questions were raised as to whether the JIT model allowed enough contingency ‘just in case’. After all, inventory levels were run down, revenues were severely impacted and liquidity was constrained. Some predicted that companies would use the experience of the crisis to localise their supply chains, increase inventory levels, or look to insourcing or vertical integration to control key elements of production more closely.

“Over the next six to 12 months, once companies have addressed their short-term liquidity needs and shored up their supply chains, we expect to see more strategic decision-making around inventory levels, cash buffers and sourcing diversification,” reflects Joao Galvao, Deutsche Bank’s Global Head of Supply Chain Finance.

However, such adjustments are not driven by the pandemic alone. Supply chain changes are as likely to be driven by other factors, such as US–China trade tensions, the need for ‘real time’ fulfilment, and environmental, social and governance (ESG) considerations.

Contingency and flexibility

In some respects, the JIT model may have helped companies to weather the early stages of the crisis. Effective JIT supply chains have risk-based contingency built in, reflecting the realities of international trade. Cross-border supply chains in particular can be hampered by unpredictable or delayed payment, leaving stock on container ships sitting outside ports. Supply or demand shocks are frequent occurrences, although in most cases these are caused by factors such as unseasonal weather, strikes or transport failures. While supply chains are often global and highly complex in nature, they are typically carefully calibrated to balance risk and cost. Given additional supply chain risks, buying the furthest away simply for cost reasons is likely to be counterproductive in the longer term.

In fact, rather than just demonstrating the limitations of JIT supply chains for certainty of supplies, the crisis has also highlighted their flexibility. Within days of governments announcing shortages of personal protective equipment, for example, fashion and luxury goods companies were producing masks, gloves and hospital scrubs. Engineering firms shifted from vacuum cleaners to ventilators. Without inherent supply chain flexibility, this could not have been achieved so quickly.

While it seems unlikely that the crisis will spell the end of JIT manufacturing, it could – and should – mark the end of poor implementation. Building supply chains based solely on lowest cost principles, for example, may create short-term competitive advantage, but squeezing suppliers on cost, and building transactional relationships rather than longer-term ones, creates significant supply chain vulnerability. It also brings environmental and social costs and risks, which have major reputational implications.

Building resilience and sustainability

Conversely, when well implemented, JIT production is not at odds with ‘just in case’ risk planning. However, one problem the crisis has exposed is the extent to which JIT shifts risk further down supply chains

to companies that are far less equipped to deal with liquidity constraints. In March, International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) quoted an International Labour Organization estimate that 24.7 million jobs in small and medium-sized enterprises were at risk,4 a number that has rapidly escalated as the extent of the crisis has become clearer. The ICC article adds that, by that time, more than US$2.7bn of orders in the Bangladeshi garment sector had been cancelled, closing thousands of factories and risking four million jobs.

‘Good’ supply chains – whether based on a JIT model or not – must focus not only on speed, cost and working capital efficiency, but also on resilience and sustainability. Many companies are already reviewing the way they identify and manage supply chain risks. While every company routinely conducts risk planning, the current situation has emphasised that these stress tests often need to be far more rigorous and extreme than would be anticipated under normal business conditions.

Extreme risk planning

"The pandemic has illustrated that behaviour can shift to a ‘new normal’ very quickly"

‘Think the unthinkable’ is often the premise of extreme risk planning, but the limits of risk managers’ imagination have perhaps been exposed. Business continuity planning, for example, often anticipated that one or more locations might be out of action, but rarely did it envisage that every location might shut down. Likewise, rather than simply building in the impact of ‘shocks’ in customer demand, the pandemic has illustrated that behaviour can shift to a ‘new normal’ very quickly. It has also shown that governments and regulators can and will act rapidly and decisively, whether through interest rates, fiscal actions, or new restrictions or permissions, creating new supply chain pressures or opportunities.

An ecosystem-wide view

Building resilience and risk planning is not an activity that can be done in isolation. Larger businesses cannot simply push risk and working capital pressure to other companies in their supply chains, as these companies will not survive, potentially crippling the entire ecosystem. Rather, as many businesses are now finding, the key to supply chain resilience is to leverage the strength of the ecosystem as a whole. This could mean financing additional capacity requirements to cater for increased or reduced demand shocks, lending to distributors to help cover short-term working capital needs during a period of reduced demand, or setting up virtual showrooms in response to new buying behaviours.

Treasury responses

During the early stages of the crisis, treasurers’ first priority was to protect their own liquidity position – a particular challenge at a time when market liquidity was constrained and commercial paper markets had dried up. Many tapped into or extended existing bank credit facilities, and some sourced liquidity through capital and equity markets to boost cash buffers. Treasurers expanded the scope of existing cash pooling structures to mobilise cash across the business and internal financing.

Having secured their own liquidity position, the next step was to build resilience across the wider supply chain. Larger companies found themselves turning to payables finance programmes to help support this.

"Supply chain financing programmes (or reverse factoring) exploded during the early stages of the crisis"

“Supply chain financing programmes (or reverse factoring) exploded during the early stages of the crisis as companies sought to shore up supply chains, leveraging their own financing capacity and credit rating to provide cost effective working capital to supply chain partners,” comments Anil Walia, Head of Supply Chain Finance EMEA at Deutsche Bank.

While these were already well established before the pandemic struck, many companies have expanded the geographic reach and number of suppliers onboarded to these programmes, targeting not only tier one suppliers, but tiers two and three as well.

“Supply chain finance programmes can be set up quite quickly, within two to three months, so long as all parties are motivated to do so,” says Deutsche Bank’s Head of Cash Management Structuring, Benjamin Madjar. He continues: “Given that every crisis ultimately impacts on liquidity, this is a valuable way of building resilience into supply chains by unlocking working capital cost-effectively without creating disadvantage for the anchor company.”

The value of resilient, sustainable supply chains and boosting resilience is not only ‘just in case’ extreme events take place. According to Bain research, investments in supply chain resilience can deliver a 15–25% improvement in output capacity and a 20–30% rise in customer satisfaction.5 These factors are both crucial to competitive advantage, and reinforce the view that cost orientation alone cannot be the driver of future supply chains.

Meeting changing customer demand

It is not only the supply side that has been affected by the crisis, but customer demand too, and this has also had significant implications for treasurers and finance managers. Some have inevitably seen a drop in income, with major revenue and working capital implications for many companies. Those that have seen a spike in demand have had to support their supply chain partners to invest in additional capacity.

Others have had to rapidly adapt to changing buying patterns. According to Adobe’s Digital Economy Index report, published in May 2020, e-commerce in the US experienced four to six years’ growth in one quarter, equivalent to 77% year-on-year.6 Consequently, treasurers need to support digital payments and new business models. Captive finance companies may also respond to reduced consumer confidence and purchasing power with consumer incentives such as financing offerings. JIT and ‘just in case’ supply chains – whether physical or financial – need not be mutually exclusive, so long as risk planning takes into account supply chains as a whole, from the smallest suppliers and distributors through to end customers. Cost and efficiency objectives will always be part of supply chain decision-making. But resilience, flexibility and sustainability (which includes ESG issues) are likely to be the factors that contribute to success over the longer term, in the new ‘business as usual’ and during future crises.

Helen Sanders is an independent treasury and transaction banking specialist, formerly editor of Treasury Management International and Director of Education at the Association of Corporate Treasurers

Sources

1 See https://bit.ly/2XU5Gk6 at unctad.org

2 See https://bit.ly/3gLN1hA at logisticsmgmt.com

3 See https://bit.ly/3iEVNPb at logisticsmgmt.com

4 See https://bit.ly/2XUKCK7 at iccwbo.org

5 See https://bit.ly/2CkBkzs at bain.com

6 See https://bit.ly/3akrLNK at forbes.com

You might be interested in

Trade finance and lending

Redefining the supply chain finance landscape Redefining the supply chain finance landscape

As Covid-19 dislocates supply chains in Southeast Asia, corporates are turning to supply chain finance to maintain their liquidity. Chito Santiago of the Asset talks to Zandy Ip and Daniel Tan about how anchor buyers are supporting their suppliers

Trade finance and lending

Beyond the invoice Beyond the invoice

Supply chain finance is growing at 20% a year, with around US$2tn in payables available for financing. But how can this be made safer and more sustainable – and accessible to SMEs? flow reports on key themes at BCR’s 4th Supply Chain Finance Summit in Amsterdam

Trade finance and lending

Deals on the ground Deals on the ground

From proprietary copper extraction technology to lighting up Egypt, flow takes a closer look at four of the Deutsche Bank deals that scooped best deal in the TFR Deals of 2016 awards.