September 2019

As China’s role on the global stage expands, Bank of China’s Yunfei Liu talks to flow about the foundations needed to build bridges in international trade, the popularity of RMB financing in Belt and Road countries, and where Western banks fit into the picture

When Yunfei Liu finished high school in Beijing, she didn’t choose a career in international trade finance; it chose her. As one of China’s new generation of professional women entering the workforce a decade after the state set about economic reform and opening up, and fired up with a passion for learning, her path was set after she took a university entrance examination to determine what she should study.

She assesses the impact this had on her future: “It is important that you do well in this examination because if you pass it, you have a chance to change your life for you and your family.”

And change her life it did. With a degree in economics and financial policymaking, one might guess that she obtained this in Beijing, China’s political and cultural centre. Instead, she headed for her mother’s home city, Shanghai – Middle Kingdom’s hub of fashion and finance – where she studied from 1987−1991. Given that most universities in China are government-owned, students are usually placed with local entities after they graduate. But Liu had worked hard and achieved high marks, so was immediately assigned to Bank of China’s graduate programme back in the Beijing head office.

This article takes a closer look at her long career with the Bank of China and provides some context around the bank’s relationship with Deutsche Bank. Their shared cultures of loyalty and passion for making trade happen have not only resulted in longevity, but have also set the tone for future bridge-building.

Client-facing

"With a legal background I would be in a better position to prevent disputes by improving our own documentation"

On joining the bank in 1991, Liu explained to the human resources department that she wanted to do “something not in management in the middle or back office, but serving clients directly”. Export trade finance fitted the bill, and as with many of today’s seasoned trade finance professionals, on-the-job grounding involved dealing with letters of credit, something that requires an eagle eye for detail. Under the industry UCP 600 letter of credit (LC) rules, issuing banks have to make payment under LCs when the conforming documents (bill of lading, invoice, etc.) are presented. When they don’t align with the terms in the LC – for example, a different port on the bill of lading – the bank can decline payment. Checking documents is a painstaking business and, at that time, the LC had not declined to its current levels of around 10% of all transaction volumes, with the remaining 90% being open account. Banks had big teams making sure all was in order and Bank of China was no exception.

After three years, having done her time at the LC coalface, Liu moved up the trade finance team ladder into the international business department. She took on a managerial role and developed trade finance policies and procedures, while also assuming operational responsibility for the management and monitoring of the bank’s branches and sub-branches.

Bank of China's Yunfei Liu talks bank-to-bank trade finance with Deutsche Bank's Jessica Jia

Barrier breaker

Today, as Deputy General Manager for Global Trade Services, Liu recalls how a willingness to learn – however mundane the task might be – and adaptability in a highly international field have helped her personal growth. She’s also passionate about her role as a mother and admits that her day job leaves less time than she would like to spend with her 10-year-old son, who “is a very understanding little man,” she smiles. And, as a working mother, she is glad her employer is also very understanding. The fact her entire career has been with one employer underlines the importance Chinese society places on loyalty; a concept which is not unfamiliar to employees of German organisations, including Deutsche Bank.

One of the skills Liu took away from her time ploughing through piles of documentary credits was how to respond to discrepancies and the resulting disputes. More often than not, these would end up in court rather than arbitration and, to her frustration, the language barrier made it difficult to communicate with the various legal representatives. She decided that it was time to go back to university: “With a legal background I would be in a better position to get to the bottom of disputes myself, and even prevent disputes by improving our own documentation.”

RMB16trn

In 1999, she enrolled with the University of International Business and Economics in Beijing on the Executive Master of Law course, while continuing her day job at the Bank of China. A few years later, the opportunity arose to apply for a UK government-sponsored scholarship to do a one-year postgraduate course in the UK, but her application was declined. With her employer’s support (they kept her job open), but funding the study herself, Liu completed a one-year postgraduate course (LLM) in International Economic Law at the University of Warwick in 2004.

The experience was pivotal. Something that struck a particular chord with her during her time in the UK was the emphasis on avoiding plagiarism (however accidental) and the rigorous approach to evidence and sources that was required for academic work. “That was brand new for us Chinese students,” she recalls. “We had to be very careful when directly or indirectly quoting from other materials or documents and include everything in references, which took even longer than the dissertation!” This discipline proved to be useful once she returned to the bank, as she was delving into the minutiae of international trade finance documentation.

Supporting China’s growth

As the oldest bank in China – it was founded in February 1912 – Bank of China has changed its function four times. From 1912 to 1928 it was the government’s central bank, then it became a government-authorised international exchange bank in 1928, and subsequently evolved into a specialised international trade bank in 1942. By 1994 the national financial system had undergone significant reform and the bank transitioned into a state-owned commercial bank, but its focus on trade, FX and exports remains part of its DNA to this day. Present in 57 countries and regions, it sees reform and innovation as its “forward path”,1 and on 1 June and 3 July 2006 respectively, Bank of China Limited was listed on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange and the Shanghai Stock Exchange.

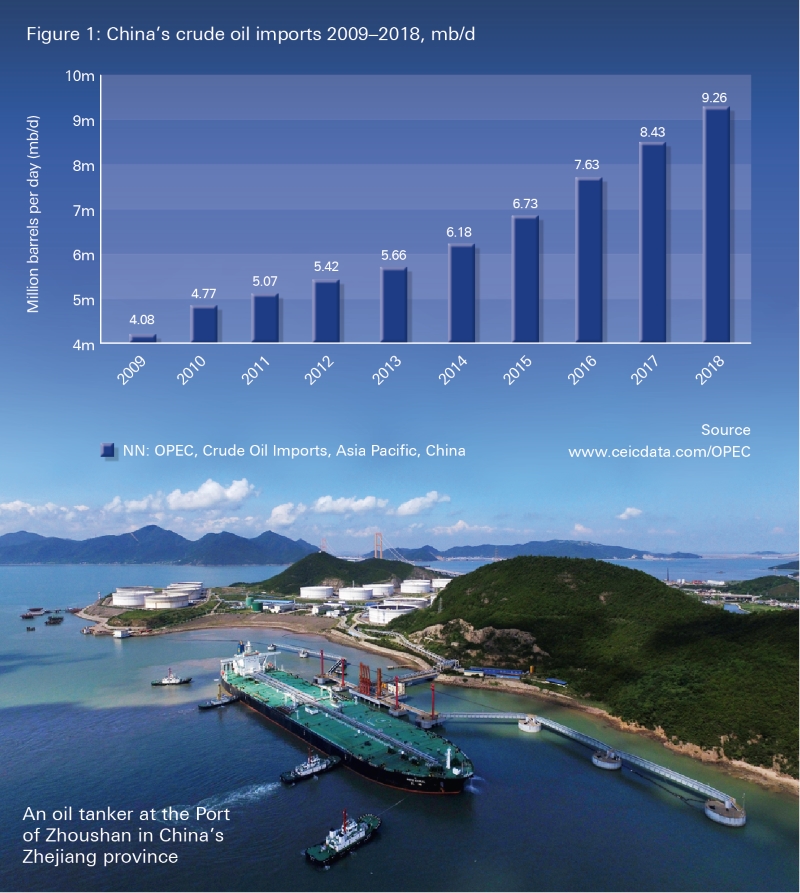

This transformation occurred at a time when the Chinese appetite for commodities was ramping up during the 1990s and 2000s to feed the country’s growth ambitions. According to the World Economic Forum,2 China’s demand equals or exceeds that of the rest of the world combined for cement, steel, copper and coal, while fossil fuel still accounts for more than 60% of the country’s power generation, and domestic coal consumption far outweighs imports.3 Around 75% of all commodity flows touch China somewhere along the way. Although GDP is no longer in double digits as China’s economy transitions from being manufacturing-led to services-led, oil import data shows no diminution in crude oil imports – Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) data charted a rise from 4,084,219 million barrels per day (mb/d) in 2009 to 9,261,414mb/d in 2018 – and the trend has continued this year.

This high-growth period, which began its momentum with China’s “open door” policy of economic reforms in December 1978, was a good time to be providing trade finance services around Chinese commodities imports and exports, and this has remained an important component of Bank of China’s business.4

Unlike many other banks, the flow and structured commodity trade finance businesses are all currently in one department, but this concentration is being analysed and potentially addressed. “As we progress and develop our commodity trade finance offering it is becoming increasingly difficult for us to handle the risks under the vanilla trade finance model,” reflects Liu. In London, Bank of China’s trade finance team is headed by colleague Ping Xiao and populated by seasoned commodity bankers who hail from Western and Japanese banks.5 “We did a lot of LCs in exporting commodities and agricultural products,” recalls Liu. However, she explains, there were some differences when dealing with commodities that her team had to be on top of – such as the fact that LCs to import crude oil required a letter of indemnity instead of a normal bill of lading.

Participants in structured commodity trade finance syndicates observe how Bank of China has what Liu reports are “big bilateral lines for all the large traders” and that they “very easily put down US$500m tickets for the large structured deals they like, such as state-owned oil companies and metals and softs on a take-and-hold basis”.

More assets please

Despite positive construction-led activity as a result of government stimulus policies, China’s overall economic deceleration has had a knock-on effect on domestic demand for trade finance. “It has become difficult for us to find the perfect project, industry or group of clients who can meet all the needs and requirements necessary for us to extend our credit,” says Liu. “This difficulty has left banks like us hungry for assets.”

Predictably there is no shortage of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in need of loans, but managing that risk – that can hardly be secured on future commodity flows – is very different. In March 2019, the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission issued new guidelines to encourage banks to increase loans to SMEs by 30% by the end of the year. The carrot? A non-performing loan ratio tolerance of three percentage points higher than the maximum rate for their overall loan book. The Financial Times noted on 13 March that “Economists have blamed a scarcity of financing for small, privately owned businesses for a recent slowdown in economic growth,” and pointed out that “banks have been wary of lending to smaller companies because default rates are higher on average”.6 “Often these SMEs are just not strong enough,” observes Liu.

Currency climb

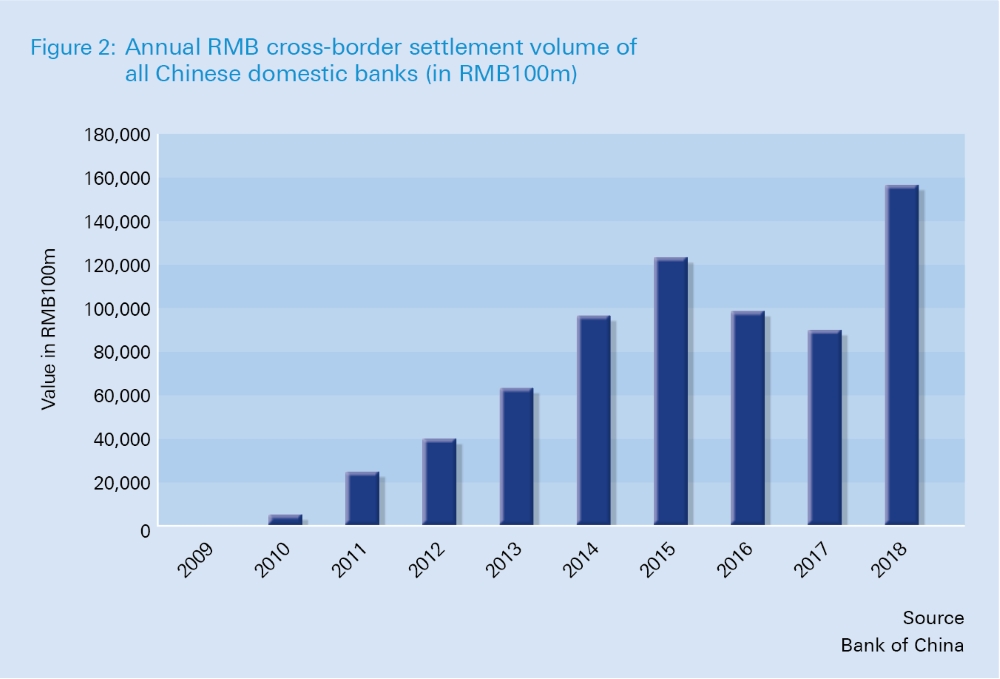

With the renminbi (RMB) – China’s offshore version of the Chinese yuan renminbi (CNY) – now the fifth most active currency for international payments by value,7 its inclusion by the International Monetary Fund as a reserve currency in November 2015 and its addition from October 2016 to the Special Drawing Rights basket of currencies, Liu is understandably optimistic about the currency’s prospects as a payment currency for commodities deals. As Washington/Beijing trade disputes show little sign of resolution in the short term, China is opening up access to RMB-denominated futures contracts. In March 2018, the Shanghai Futures Exchange started trading CNY-denominated crude oil, turning over CNY17.1trn (US$2.48trn) during the following 12 months. Plans to launch rubber and non-ferrous metals contracts were announced in May 2019.8 Liu points out this is something of a first: “China’s futures exchange opening up to foreign investors represents an important step.”

Liu is understandably enthusiastic about the financing opportunities from China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).9 Many of the countries within the BRI are still developing economies and cannot access dollar liquidity. Reluctant to pay the high interest rates charged for local currency, they are turning to Chinese banks for RMB financing. “Some of the commercial banks in Pakistan are communicating with us to refinance in RMB in order to help their local trade and complement their liquidity,” explains Liu.

Liu says that one big challenge in handling cross-border transactions in China is that “you have to comprehend more than 200 sets of policies and rules governing cross-border transactions, the majority of which come from the State Administration of Foreign Exchange, with a few from China’s central bank, The People’s Bank of China”. Liu holds regular team meetings “to discuss different types of issues, from policy level through to operational level”. She believes that this helps to foster an ethos of teamwork, with everyone learning from each other.

"China’s futures exchange opening up to foreign investors represents an important step"

Yunfei Liu with her team at Bank of China's head office

Profile: Yunfei Liu

Current role: Deputy General Manager, Transaction Banking Department (formerly Global Trade Services Department), Bank of China Head Office, Beijing

- 2017: Appointed as a Member of the ICC Banking Commission’s Advisory Board

- 2003−2004: LLM in International Economic Law, University of Warwick (Coventry, UK)

- 1999−2005: Team Head, Global Trade Services, Bank of China Head Office, Beijing

- 1999−2002: Executive Master of Law, University of International Business and Economics, Beijing

- 1995−1998: Assistant Manager and Deputy Manager, International Business Department of Bank of China Head Office, Beijing

- 1991−1995: Officer, Banking Department of Bank of China Head Office, Beijing

- 1987−1991: Bachelor’s degree, International Finance (Economics) at Fudan University, Shanghai

Four pillars of support

Liu outlines that Bank of China’s relationship with Western banks is based on four principles:

- Best of breed. Banking partners have to be “peers in their markets”, she says. “It is about building a bridge across the ocean. And to make this bridge secure we need solid foundations for Chinese enterprises on this side. Similarly, the Western bank on the other side should be the foundation for the bridge to support the counterparties.”

- Corporate relationships. While Bank of China supports Chinese clients overseas via its foreign branches, Liu says these are quite small, and, reciprocally, Western bank branches are also quite small in China, so head office cooperation makes it easier to “create links with the mainstream local enterprises offshore”.

- Credit support. As the BRI puts down roots in regions where Bank of China has a shortage of credit support, it needs its Western bank partners to help out. This includes Latin America, Southeast Asia and Africa, where Chinese corporates see particular opportunities for infrastructure investment.

- Structuring expertise. Liu has been inspired by Western banks when it comes to “innovative techniques and new structured finance tools”, hence the recent additions to the commodity trade finance teams.

Rose Zhu, Vice Chairman and President of Deutsche Bank China, reflects: “Bank of China is one of Deutsche Bank’s most distinguished clients. It gives me huge pleasure to witness the success of the collaboration with an institution that I regard as the most globalised and integrated bank in China.” Jessica Jia, Head of Trade Finance Financial Institutions China at Deutsche Bank, adds that the relationship spans “structured commodities trade finance, structured export finance, trade finance flow, cash management and FX as well as global markets”.

Outlook for trade services

Bank of China would not be where it is today without constant innovation and seeking new ways of delivering client services. “Our biggest issue for us in trade finance is that we are transitioning into a wider transactional banking operation,” Liu explains. She admits the inspiration for this partially came from Deutsche Bank (now transitioned again into the current Corporate Bank) and Citi. “Clients need the full package, not just trade finance. They need to manage liquidity, investments, real-time payments and online banking services. So there is a long way to go and there are always new things to learn.”

When Deng Xiaoping embarked upon his economic reforms, in a speech to the Communist Party Plenary in 1978, he compared the process to that of “crossing a river by feeling the stones”. Yunfei Liu’s remarkable story offers the sense of someone who had not only reached the opposite bank, but was already on her way to many more waterways.

Sources

1 See https://bit.ly/2OnTeRX at boc.cn/en

2 See https://bit.ly/2MXOjKv at weforum.org

3 See https://bit.ly/2KPz9nZ at visualcapitalist.com

4 See https://bbc.in/2KOUttM at bbc.co.uk/news

5 See https://bit.ly/2MSe2DO at gtreview.com

6 See https://on.ft.com/2EY686r at ft.com

7 See SWIFT RMB Tracker https://bit.ly/2ZK3KcN at swift.com

8 See https://bit.ly/31aEqxp at scmp.com

9 See the World Bank overview https://bit.ly/2QNZ4OL at worldbank.org

Go to Corporate Bank EXPLORE MORE

Find out more about products and services

Go to Corporate Bank Go to Corporate BankStay up-to-date with

Sign-up flow newsbites

Choose your preferred banking topics and we will send you updated emails based on your selection

Sign-up Sign-upSubscribe Subscribe to our magazine

flow magazine is published annually and can be read online and delivered to your door in print

You might be interested in

TRADE FINANCE, CASH MANAGEMENT

Bumpy road or motorway? Bumpy road or motorway?

After LIBOR, digitalisation and future proofing were among the “trends to shape a new decade” discussed by delegates at the 2020 BAFT Global Annual Meeting in Frankfurt

TRADE FINANCE, EXPORT FINANCE {icon-book}

Building healthcare Building healthcare

Well before the advent of Covid-19, plans were under way for better healthcare infrastructure in Côte d’Ivoire to support GDP growth momentum. flow reports on a project to build hospitals and additional facilities in the towns of Aboisso and Adzopé

Trade finance and lending

Farewell to trade barriers? Farewell to trade barriers?

At the close of an extraordinary year, eyes are on growth forecasts for 2021 as economies climb out of Covid-19. But for these to materialise, trade needs to move back towards multilateralism, explains Dr Rebecca Harding