May 2020

Floods, political upheaval and investor caution have created infrastructure shortfalls in much of Latin America. Ivan Castano Freeman reviews project progress, re-routed trade flows, and opportunities for banks and export credit agencies

After a 2019 that saw an average of nil economic growth across South America, market observers note that the region is poised for a cyclical recovery, with its two largest economies – Brazil and Mexico – offsetting the impact of further potential political turmoil with stronger exports and ambitious infrastructure expansion.

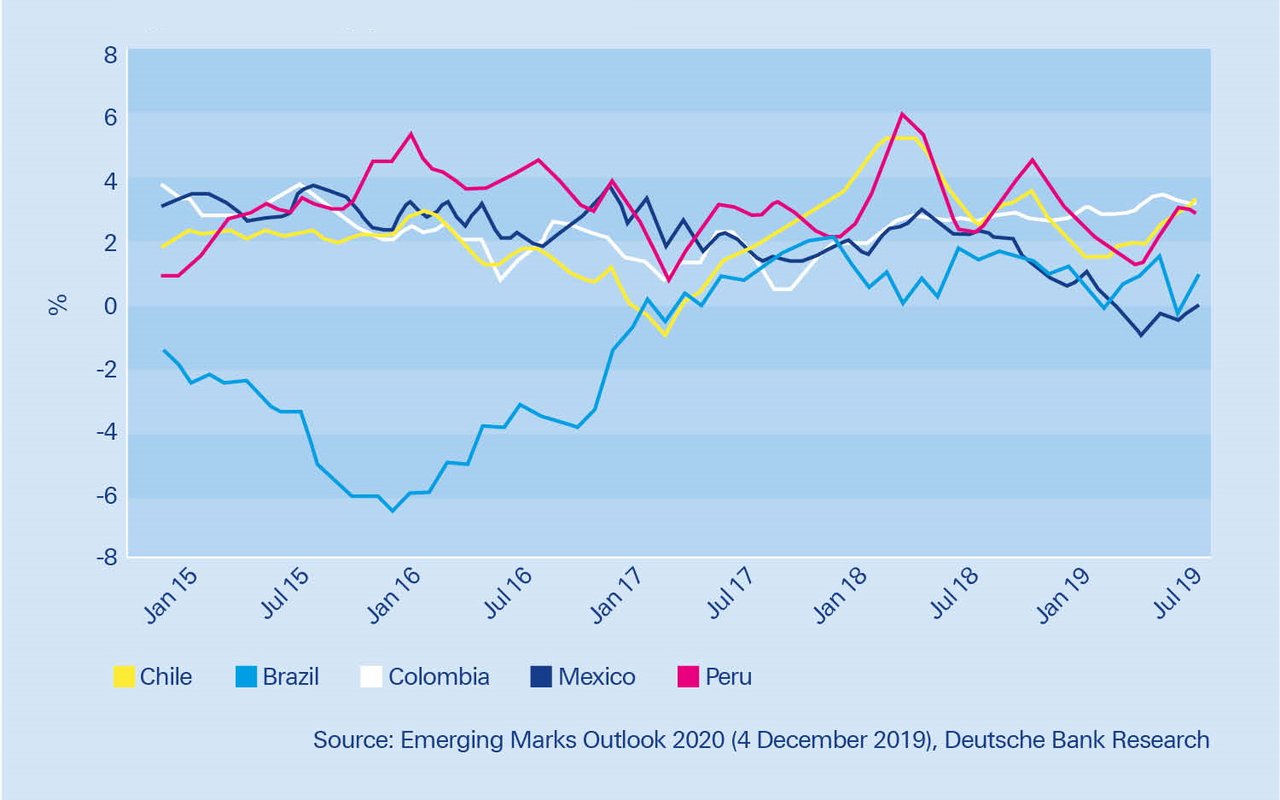

Prospects for the region’s other members are a little less upbeat. “Activity in the rest of Latin America will also accelerate, but idiosyncratic events remain more relevant than cyclical considerations,” commented Deutsche Bank’s Emerging Markets Monthly team at the end of 2019.1 Examples of these events thus far have included civilian unrest, natural disasters and corruption scandals. Will the new decade offer more of the same, or greater stability? Either way, it could well be something of a turning point.

This article takes a closer look at what is driving the supply and demand of trade finance in the main regions, and what governments are doing to attract lenders.

Construction resurgence

“Mexico is launching an infrastructure plan that will need international banks and boost trade finance operations,” says Ignacio Méndez, Vice President of Structured Trade and Export Finance (STEF) at Deutsche Bank. The country has seen many foreign construction firms moving to participate in the initiative, which has helped to fuel Mexico’s GDP to a projected 1.2% for 2020 from the zero growth seen last year.

The five-year scheme’s first phase will see private investors team up with Mexico’s government to plough MXN859bn (US$46bn) into 147 projects spread across the energy, transportation, tourism and telecommunications sectors.

The plan “won’t come right out of the budget,” explains colleague Ignacio Ramiro, the bank’s Head of STEF Iberia. “These companies will need financing solutions and we are constantly receiving proposals from different clients to pursue different opportunities within the plan.”

By way of context, Mexico’s contraction in public expenditure, along with the impact of transitory shocks such as gasoline shortages and strikes, helped to push the economy into technical recession in the first half of 2019, noted the authors of a Deloitte Insights report published in December 2019.2 However, international trade has remained, the report explains, “another positive sign for the Mexican economy”. The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development stated that the US–China conflict has helped Mexico to the tune of US$3.5bn from additional exports to the US market – specifically in the agro-industry, transportation equipment and electrical machinery sectors.

The recent United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement (USMCA), which has upended the US$1.2trn free-trade corridor between the US, Canada and Mexico, is fuelling demand for transaction banking services and is set to keep trade banks busy. The boost comes after many lenders suffered from anaemic revenue growth in 2019 when President Andrés Manuel López Obrador scrapped plans for a glitzy US$13bn airport for Mexico City, spooking global investors.

Figure 1: Activity poised to rebound

As clients assess projects, Méndez says demand for risk-mitigating products such as factoring or invoice discounting is growing sharply. “Exporters are extending payment terms to their clients to gain competitive advantage,” he explains, adding that this activity is poised to gain traction in 2020. “Trade finance houses are engaged to buy these receivables, so exporters reduce their overall exposure to buyers and provide more attractive conditions without affecting their liquidity.”

Meanwhile, Mexico’s state-owned Banco Nacional de Comercio Exterior (Bancomext) expects the infrastructure drive, coupled with rising Mexican shipments north of the border, to ramp up demand for its guarantee and other export-financing products.

“We expect this infrastructure spending to be a big detonator of economic growth, helping both large and small companies grow by enabling them to do more trade and demand trade finance products,” enthuses Héctor Gómez, Vice President of International Factoring at Bancomext. He forecasts that Bancomext will likely grow its credit guarantees to MXN560m (US$30m) this year, up 2.7% from 2019, as a string of companies leap into new US markets, boosting Mexican shipments to 6% from 4.7% in 2019.

"In Peru it is rare that one form of financing or structure solves everything"

Overall, Bancomext hopes to grow its export financing activity by 6% to US$4.3m as it acts to support 22 industrial sectors ranging from automotive and auto-parts (expected to benefit from the USMCA) to energy, electrical equipment, renewable energy and aircraft engines, both on its own and in partnership with financial institutions such as Deutsche Bank, Wells Fargo and Citi, Gómez reveals.

Colombia’s construction market is also heating up. Bogota is reportedly set to auction at least 10 new highway concessions worth US$4bn in the second half of 2020, which is drawing strong interest from British, US and Chinese players looking to participate in major highway and airport concessions. In common with Mexico, the initiatives will fuel Colombia’s GDP expansion, which is forecast to reach 3.6% this year; one of the fastest rates in Latin America.

Hungry China

Brazil will also drive transactions growth this year. Latin America’s largest economy is expected to gain 2%, versus 1.1% in 2019, when a sharp fall in exports saw Brazil’s trade surplus shrink by 20% to a four-year low, impacting on GDP and dragging the region’s aggregate to -2%.

Already, farmers are upbeat about an expected surge in pork and chicken exports to China, as a worsening African swine fever outbreak lifts demand for meat. “Some 40% of Chinese pigs – hundreds of millions of animals – have now been lost, and the result has been a chronic shortage of pork and rocketing prices,” reported The Guardian in November 2019.3

According to the Brazilian Animal Protein Association, pork and chicken sales to China and Hong Kong, as well as to Vietnam, Russia and Chile, will gain 15% and 7% respectively this year – although the coronavirus outbreak could necessitate major revisions to a host of projections.

Zooming out to the whole region, initial forecasts are for exports to increase by between 2%–5% amid a recovery in key commodity prices such as oil and copper, which could partially offset falling soybean sales to China as the ‘phase one’ deal to end the trade war4 redirects purchases to the US, hurting suppliers in Brazil and Argentina.

“We have to see what the phase one deal does to Brazil soybean exports, which are a big deal for the country,” says Capital Economics’ Chief Emerging Markets Economist William Jackson, who adds that soybean shipments hover at US$27bn, or 1% of GDP. Rising beef exports (though this is still a small category), higher crude prices and a ramp-up of iron ore shipments could help offset those losses, however, boosting overall exports by 1% to 2%, he adds.

China’s economic growth (as well as a possible deterioration of its trade relationship with the US) will be closely watched. The latest World Bank statistics pin expansion at 5.9%, down from 6.1% in 2019, a year that saw the world’s second-largest economy expand at its slowest pace in three decades. The coronavirus pandemic suggests further downward revisions will follow.

Argentina and Chile

Deutsche Bank’s Méndez also sees growth perking up in Argentina, despite the country’s debt and economic crisis – although this is contingent on a successful revamp of its debt load, including US$100bn of bond restructuring.

“The first 100 days of President Alberto Fernández’s mandate will be crucial to see whether Argentina will grow,” says Méndez, adding that if the process yields a satisfactory conclusion, the nation could see a resurrection of its massive Vaca Muerta shale gas project.

Vaca Muerta (literally meaning “dead cow” in Spanish) has the potential to export US$20bn worth of shale oil and gas by 2024, if Argentina can garner enough investment to complete the project, analysts say. Because Vaca Muerta is located in the Neuquén Basin deep in Argentina’s Patagonia region, ferrying its output will require big investments in distribution and transmission infrastructure, boosting deal flows for trade banks.

“Talks on infrastructure projects around Vaca Muerta have been ongoing for several years,” Méndez reveals. “These are focused on exploiting the area’s potential and guaranteeing its output has access to international markets.” To make this happen, banks will likely partner with multilaterals to import equipment and technology, using custom-made financing solutions involving bonds, commercial credits, supply chain finance and ECA- (export credit agency) backed solutions, he adds.

Meanwhile, in neighbouring Chile, the outcome of a referendum scheduled for 26 April could help build a fairer and more equitable nation, and alleviate tensions related to the violent protests of 2019, which were sparked by demands for social reform and constitutional change. If peace returns, funding demand to ramp up staples of copper ore, refined copper and forestry exports, as well as to maintain commodity houses’ business operations, should continue to increase, Méndez notes.

Social infrastructure

Despite the upheaval surrounding the protests, which have engulfed other Latin American countries, governments are working to improve their social infrastructure and services, with plans afoot to build new schools and hospitals.

Piers Constable, Managing Director, Head of the Americas at Deutsche Bank’s STEF division, says his team is helping to finance such projects in Argentina and Ecuador this year5 and expects similar initiatives to emerge in the future.

“In Argentina and Ecuador, there is a very strong focus on the governments improving social welfare,” says Constable. “These are not projects with which it’s easy to generate private sector financing, as they don’t generate hard currency income.”

"We have a constant flow of small and mid-size businesses looking for bonds or working capital"

In other countries, Deutsche Bank remains active in funding public–private partnership infrastructure projects, working with administrations and corporate borrowers to hammer out different types of financing solutions.

Depending on the country or client’s liquidity profile, executing these deals brings its own set of challenges, according to Constable. Some local markets are awash with liquidity (Brazil, for instance, boasts a strong domestic fixed-income market), making it difficult for the bank and other foreign peers to provide competitively priced, long-tenor financing. “We don’t have a significant local currency deposit base, so when we see clients issuing 20 to 25-year local debentures, our structured finance team struggles to be relevant in that landscape,” Constable reflects.

Structuring deals

As the private financial sector navigates projects in Peru, which is pursuing a US$7.8bn reconstruction programme following the devastating floods in early 2017, banks are working to launch creative financing structures that often bring development banks or ECAs into the fold.

The Peruvian government implemented its ‘Preliminary Plan for Reconstruction con Cambios’ in June 2017 in response to the floods crisis, and announced a three-year period of reconstruction. A Zurich Flood Resilience Alliance ‘Post-Event Review Capability’ study observed that “too often, disaster reconstruction is done hastily in an effort to return things to ‘normal’”, and that reconstruction should be used as an opportunity to “build back better” developing systems and services to address core weaknesses at their foundation.6

In September 2019, President Martín Vizcarra said that Peru had 52 infrastructure projects under way involving around US$30bn up to 2025, 24 of which were under construction at the time. The then finance minister Carlos Oliva added that Peru had recalculated its infrastructure shortfall at 363bn soles; almost half of its GDP (US$109bn).7

“In Peru, which has one of the largest infrastructure systems in the region, it is rare that one form of financing or structure solves everything,” says Constable. Jumbo projects often require structured finance solutions splitting financing into tranches.

“For the US$2bn, US$3bn and/or US$4bn petrochemical, liquefied natural gas or gas sectors, for example, we often see tranche financing,” Constable notes. “Say there is only liquidity in the capital markets for US$1bn to US$2bn, but there is another US$1bn or US$2bn in the export credit market or trade finance market. We can bring all of that into the project to diversify our client funding sources,” he explains.

The ECA-backed US$1.3bn financing of state-owned Petroperú’s overall US$5.4bn Talara refinery upgrade is a good example of such a structure, Constable recalls. In this deal, Deutsche Bank acted as facility agent for a syndicate involving CESCE, Spain’s ECA − which made its largest ever commitment in the project – together with BBVA, BNP Paribas, Citi, HSBC and JP Morgan. The Talara expansion project is due for completion by the end of 2020.

According to CESCE, this deal is quite exceptional because, for more than a decade, deals in Latin America have tended to be small or medium in size, and solid infrastructure ECA exposure in Peru was almost non-existent until about three years ago.

Pipeline extension

US$7.8bn

CESCE intends to swing into action in Latin America, but with much smaller deals than Petroperú typically accommodates, reports Beatriz Reguero, Chief Operating Officer of State Account Business at CESCE. “This year, we could grow a little,” she says, adding that despite the outlook, CESCE remains open in all main Latin America markets and is willing to increase exposure in them. So far, however, the Madrid-based institution hopes to close two hospital projects in Argentina worth roughly €80m.

The rest of the deal pipeline could come from Spanish corporates looking to grow their franchises across the pond. Increasingly, firms are contacting their banks for an ‘aval’ or guarantee. To hedge its lending capabilities, the bank then goes to CESCE for a counter-guarantee.

“We have a constant flow of small and mid-size businesses looking for bonds or working capital for road construction, renewable energy and many other projects in Mexico, Panama or Paraguay,” Reguero observes, citing a few examples of the types of deals coming across her desk.

For firms looking to invest in the region, CESCE can help. “With our bonds or working capital cover, a bank can take 50% more client risk. So if they have a US$100m credit line, for example, they can increase it to US$200m,” Reguero concludes. That should lend wind to the sails of companies looking to take advantage of Latin America’s massive infrastructure spend, with their incursions coming at a particularly poignant time in the region’s history.

Ivan Castano Freeman is a freelance financial journalist based in Mexico City

Sources

1 See Emerging Marks Outlook 2020 (4 December 2019), Deutsche Bank Research

2 See https://bit.ly/2SeYSuM at deloitte.com

3 See https://bit.ly/31IAFQH at theguardian.com

4 See https://bit.ly/31IAFQH at theguardian.com

5 See From the rubble at corporates.db.com

6 See https://bit.ly/3bpTtaL at floodresilience.net

7 See https://bit.ly/2SdYUD0 at bnamericas.com

You might be interested in

Trade finance and lending {icon-book}

Call for capacity Call for capacity

Trade finance shortages remain a barrier to developing world economic growth, as the gap between the perception and actual level of transaction risk widens. Tackling this is an ongoing priority, says the WTO’s Marc Auboin

Trade finance and lending

Trade re-set? Trade re-set?

Independent economist Rebecca Harding shares three reasons why she believes trade will never be quite the same again

Trade finance and lending {icon-book}

Market makeover Market makeover

Thanks to some transformational lending, Ghana’s Kumasi Market is undergoing a makeover that is set to transform the Ashanti economy and all it touches. flow tells the story of a project involving three governments, a Brazilian contractor and Deutsche Bank’s Structured Trade & Export Finance team