29 May 2020

The journey towards tomorrow’s cashless society has gathered momentum and urgency as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic, reports flow’s Graham Buck

Originally used to refer to money obtained dishonestly, the term “filthy lucre” has taken on a whole new meaning since the onset of Covid-19 with concerns that banknotes and coins can, potentially, transmit the virus.

Transmission risk

Several reports have suggested that cash is as likely to carry the virus as door handles and other surfaces. The Bank of Thailand went so far as suggesting that citizens could disinfect banknotes through a short soak in soap solution or dishwashing liquid before rinsing with water, gently dabbing them with a cloth and leaving them to dry. It added that people should not attempt to clean notes with washing powder or bleach, or try to bake or boil them, which would damage the notes.1

There were even reports in early March 2020 by several media outlets that the World Health Organisation (WHO) was cautioning against using banknotes and coins and had recommended that businesses and consumers opt for cashless options wherever possible to limit the potential spread of the pandemic. The WHO quickly clarified that while it was advising the public to wash their hands after handling money, especially if touching or eating food, this did not constitute a warning against using banknotes.

At the beginning of March, the US had registered no more than 60 cases of Covid-19 and six deaths. So what might then have seemed overly alarmist has increasingly looked like sensible advice, with studies suggesting that the influenza virus can remain as potentially infectious on banknotes for as long as 17 days.2 While many probably never thought about it before now, consumers can disinfect their smartphone or plastic card with a quick wipe rather more easily than notes and coins. Our first Covid-19 dossier article, Coping with Covid-19 reported how China’s government took the alert a step further according to reports, by disinfecting and even destroying banknotes that had possibly been handled by individuals with the virus (a policy also adopted by the central banks of South Korea, Hungary and Kuwait).3

According to Hong Kong daily the South China Morning Post4 a local branch of the People’s Bank of China in Guangdong province was destroying money thought to have circulated through high-risk locations such as hospitals and food markets. The concerns also reached the US Federal Reserve, which introduced quarantine measures for physical dollars received from Asia in case any were contaminated.

Tap and go

As a further incentive for its consumers to move away from cash for regular daily purchases, the UK was quick to raise the limit applied to contactless payments at the start of April from £30 to £45. The cap on ‘tap and go’ contactless cards was initially set at just £10 back in 2007; subsequently increasing to £15 in 2010, £20 in 2012 and £30 in 2015.

Similar increases for contactless have been authorised across many other countries over recent weeks, as per Figure 1 below.

Figure 1 – Contactless payment limit increases in response to Covid-19

1. To be implemented “by the end of 2020”.

Source: NFC World

“Covid-19 is definitely speeding up the trend towards contactless payments, which many now prefer over cash so they can respect social distancing and avoid contact with other people,” says Deutsche Bank Research analyst Marion Laboure. Indeed, shortly before temporarily closing its doors in mid-March in response to the pandemic, Paris’s Louvre Museum had already stopped accepting cash payments and would only accept contactless; a policy that has also been adopted by many retailers.

Despite this, a Deutsche Bank Research report, Paying in times of crisis, issued on 26 May found that cash was in high demand across Europe at the start of the pandemic.5 Its author, analyst Heike Mai, reported that in March euro circulation rose by €36bn month on month; nearly half the volume consisting of smaller banknotes used by consumers for everyday purchases. That marked a change from the 2008-09 financial crisis, when cash demand also rose but larger banknotes were favoured because of their “safe haven” status.

Digital payment catalyst

In January 2020, Laboure and Deutsche Bank’s Head of Thematic Research Jim Reid published their three-part research paper The Future of Payments. Part 1 considered the future of cash and concluded that while it was a ‘dinosaur’ and likely to be rapidly supplanted by digital payments in the 2020s, cash would outlive the plastic card, which faced extinction. “Over the next five years, we expect mobile payments to comprise two-fifths of in-store purchases in the US, quadruple the current level,” they predicted.

"Covid-19 might be the catalyst that finally brings digital payments more fully into the mainstream."

In the latest issue of Deutsche Bank’s konzept magazine – whose theme is the world post-coronavirus – she opens a section entitled ‘Cash is not immune to the virus’ with the premise: “Covid-19 might be the catalyst that finally brings digital payments more fully into the mainstream. That is because the global spread of the virus is forcing countries to reconsider the use of physical money, which might transmit the disease.”

Concerns over handling cash have added to the impetus for central banks to create their own digital currencies, or CBDCs, which have already been in development over the past couple of years. “Today, 80% of them are developing a CBDC and the work goes far beyond research: 40% of central banks are experimenting with proofs of concept and 10% are already running pilot projects,” reports Laboure. “Looking ahead, countries representing about a fifth of the world’s population are likely to issue a general purpose CBDC in the next three years.”

The People’s Bank of China (PBOC) is at the forefront of these initiatives and has begun trialling some very low-profile payments in its new digital currency – reportedly with both Starbucks and McDonalds on board. In a separate article, Online grocery: fad or fate, konzept looks at the upsurge in demand for grocery shopping online since the pandemic began.

Analyst Nizla Naizer notes: “Given the nature of the crisis, where social interaction can lead to the virus spreading faster, it is natural that people look for options to source food without having to physically enter a supermarket.” The pandemic’s impact has prompted several grocers who haven’t previously offered online purchasing options – such as Aldi in the UK – to begin doing so.

From a fairly low level, adoption of and familiarity with ordering online was already beginning to improve pre-Covid-19. It’s likely that pandemic will further accelerate the trend and if fewer consumers return to the stores when more normal conditions return, the use of cash is likely to further decline.

The rate at which it does so will vary from country to country, Sweden, which some years ago announced the end of cash, aims to become the world’s first cashless society by March 2023. Progress towards this goal was helped by the 2012 launch of the payments app Swish, which has the backing of the country’s main banks and is used by two in three Swedes.

Today, cash in circulation represents only 1% of GDP – against 11% for the Eurozone and 8% for the US. In February Sweden’s Riksbank announced the launch of a year-long pilot of its own digital currency, the e-krona, which take it nearer to the creation of the world’s first CBDC – although the Riksbank describes it as a “complement to cash” rather than a replacement.6

By contrast, Deutsche Bank’s research suggests that Americans and Western Europeans are much more dependent on cash. “It takes much longer to change the ingrained habits of people in a legacy system,” comments Laboure. “In terms of disease control, this could be a significant problem, especially in cash-based societies where populations are ageing, such as the US or Germany.” (Even in Sweden there are still rumblings of dissent that the drive to cashless neglects the needs of the elderly, people living in rural communities and workers on low wages.)

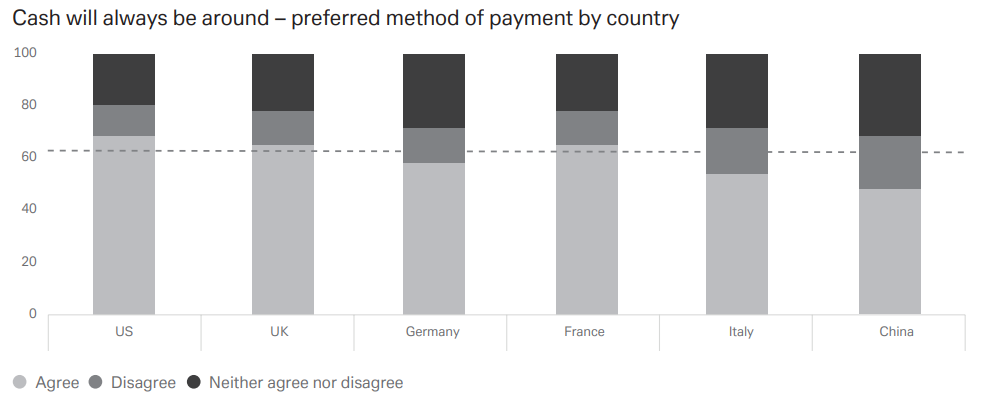

Figure 2 – Popularity of cash

Note: percentage of respondents who think cash will always be around

Source: Deutsche Bank dbDIG

With the exception of Sweden, where the use of physical cash is actually declining. According to a nationwide survey conducted by the Sveriges Riksbank—the Swedish central bank—only 18 percent of Swedes reported using cash recently compared to 40 percent of Swedes in 2010. Factors that help include strong 1 broadband coverage, even in remote areas; a small, tech-savvy population; and deeper trust in institutions and new technologies.

The mantra “cash is king” has been particularly entrenched in Germany until quite recently. In The future of payments, Laboure and Reid reported that a survey showed that nearly 60% of in-store purchases in Germany were paid in cash and on average each German held €52, the highest rate among advanced economies and many were planning to use even more cash in the months ahead. Unlike Swedish retail outlets, many of which announce that they are fully contactless, German corner shops and neighbourhood restaurants have depended on cash payments until this year.

Things are now changing fast and “over the past few weeks, more than half of card payments have been done contactless, versus a third in December in Germany,” says Laboure – a finding further confirmed in Mai’s 26 May report that stated consumers “wish to protect themselves against infection and because the retail sector requests that they avoid cash”.

However, Laboure adds that the pandemic hasn’t changed her belief that the bank card will have disappeared by 2030 but cash will outlive it, noting that the status of cash as “a store of value” typically increases in times of crisis and people tend to withdraw it and hold it in reserve.

And while an affluent country such as Sweden might be able to abolish cash, it’s much harder for countries to accomplish where a sizeable proportion of the population are financially excluded – unless or until a credible alternative to cash is developed.

Leeway for Libra

The headlines devoted to Covid-19 and its impact means that, after making a splash last June when it was first announced, Libra − the cryptocurrency planned by Facebook and its partners − has been out of the limelight in recent months.

After a series of criticisms from regulators and authorities last autumn and the departure of several founder members, at the beginning of 2020 there appeared to be “zero chance” that Libra could successfully launch by the end of this year, says Laboure. However, last month the Libra Association released its White Paper 2.0, a “less audacious and less controversial” version of the original concept, in which Facebook attempts to appease regulators, policymakers, central bankers and various stakeholders by addressing their main concerns.7

“Facebook strategy has shifted, with more emphasis on cheapening up payments rather than competing with governments on creating a parallel means of payments,” comments Laboure. With nearly 2.5 billion users, or a third of the world’s population, Facebook now has “the potential to compete with traditional online payment platforms and advance digital currencies into the mainstream.

Hardly had these words been spoken than on 19 May Facebook announced the launch of Shops, a new feature enabling merchants to create online shops to display and sell products on the Facebook and Instagram apps. The business case rests on two main pillars: revenues from payments (Facebook’s checkout service) and more data to improve and grow advertisement income. Facebook Shops could also mark a further chapter in the steady decline of cash.

Summary of Deutsche Bank reports referenced

- Future Payments: Coronavirus: infectious cash & digital payments, 5 March 2020, by Marion Laboure

- Future Payments: COVID-19 pandemic accelerates the rise of central bank digital currencies, 2 April ,by Marion Laboure

- Future Payments: Facebook Libra 2020: growing up into reality, 6 May 2020 by Marion Laboure

- konzept # 18: Life after covid-19 (pages 49 and 70, 14 May 2020) Deutsche Bank Thematic Research

Sources

1 See https://bit.ly/36GCZKr at nationthailand.com

2 See https://bit.ly/36xrXqX at ecdc.europa.eu

3 See Coping with Covid-19 at flow.db.com

4 See https://bit.ly/2M0gtCV at scmp.com

5 See https://bit.ly/2X8Q4Jn at scmp.com

6 See https://reut.rs/2X4NUuk at reuters.com

7 See https://bit.ly/3d9V1XN at libra.org

Go to Corporate Bank EXPLORE MORE

Find out more about products and services

Go to Corporate Bank Go to Corporate BankStay up-to-date with

Sign-up flow newsbites

Choose your preferred banking topics and we will send you updated emails based on your selection

Sign-up Sign-upYou might be interested in

Macro and markets, Cash management, Trade finance and lending

Coping with Covid-19 Coping with Covid-19

With the coronavirus now pronounced a pandemic by the World Health Organisation and lockdown imposed on more regions and cities, what will be the impact on the global economy? flow reviews extracts from Deutsche Bank research

CASH MANAGEMENT

Corporate tips for navigating Covid-19 Corporate tips for navigating Covid-19

COVID-19 has precipitated a global shock that poses significant risk for business. To assist in this situation, Deutsche Bank’s Capital Markets Strategy team provides a detailed checklist for operational, funding and risk management functions

MACRO AND MARKETS, TECHNOLOGY

Moving out of Covid-19 Moving out of Covid-19

The global Covid-19 crisis response during transition from lockdown to gradual reopening is at a critical juncture. Clarissa Dann summarises recent Deutsche Bank research and analysis