14 May 2021

While anti-Covid vaccine rollouts have helped some regions lift coronavirus restrictions, limited access to labour could also limit economic recovery. flow’s Graham Buck and Clarissa Dann review sectors at risk and what this means for employers and governments

MINUTES min read

After months of Covid-19 containment restrictions, a cleared path back to economic recovery beckons. But how available are the essential factors of production?

“The lasting economic impact of the coronavirus pandemic will become apparent in the development of the macroeconomic factors of production – labour, capital, human capital as well as the stock of technical knowledge,” notes Michael Grömling, of the German Economic Institute in COVID-19 and the Growth Potential.1

He makes the point that the pandemic forced firms to find technical solutions to the discontinuation of normal business operations (for example working from home), creating “greater openness to innovation in business and social life”. But on the flip side, geopolitical risks and protectionist attitudes that predate the crisis are intensified, reducing the migration of skilled labour over the long term.

However, at a rather more basic and immediate level in developed economies such as the US, UK and the EU, there is a wider more acute problem – shortages of workers in a number of industries supporting economic growth as countries relax restrictions, such as construction, some areas of hospitality and healthcare. For example, in the UK, a Confederation of British Industry survey in early 2021 highlighted how shortages of low-wage workers and supplies have risen more sharply than in almost 50 years, exacerbated by Covid-19 disruptions and the aftermath of leaving the EU.2

In addition to pandemic-related worker shortages, demographics are also at play and have been so for several years, with some industries failing to attract enough new entrants to replace retiring workers. For example the Japanese labour market is characterised by low unemployment and high employment rates – resulting, according to the OECD, in a labour market performance above its average. However, the OECD adds that structural changes such as technological progress and an ageing population “are transforming the supply of and demand for skills”. Unless education and training systems respond to this, the country’s productivity and economic growth are at risk.3

April wake-up call

"Companies need to outbid the government to get workers"

The US April payroll figures caught many by surprise. With a non-farm payroll increase of only 266,000 (earlier Dow Jones estimates had been for one million new jobs and an unemployment rate of 5.8%), This upset, notes Deutsche Bank Strategist Jim Reid, “is highly indicative of how difficult it is to hire at the moment as the economy fires back”. 4 US National Federation of Independent Business data (see Figure 1) demonstrates how job openings are particularly hard to fill in the current recession. 5 NFIB Chief Economist Bill Dunkelberg commented, “Finding qualified employees remains the biggest challenge for small businesses and is slowing economic growth.”

Reid explains, “This is a something that only happens late cycle and definitely not at the start. Some of this is in the logistics of hiring in a pandemic, and some of this is likely that the fiscal support is so generous that the incentive to rush back is low for many. There are signs this is leading to higher wages. One way to look at this is that companies need to outbid the government to get workers.”

Expectations that the US economic recovery was gaining pace had their roots in the success of its anti-Covid vaccination programme and the roll-out of the Biden fiscal stimulus strategy in the form of the latest batch of US$1,400 cheques dispatched in April to many American workers.6

Figure 1: NFIB Small Business Survey: Job openings hard to fill (recessions shaded)

Source : NFIB, Bloomberg Finance LP, Deutsche Bank

Why did US employers hire far fewer workers than expected? The Economist’s report stated that “although employers in the leisure and hospitality sectors seemed especially keen to take on new workers, adding 331,000 staff last month, other sectors shed jobs”. The official explanation from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics7 was that “job gains in leisure and hospitality, other services, and local government education were partly offset by losses in temporary help services and in couriers and messengers”.

The data was also analysed in the 7 May Deutsche Bank Research white paper US Economic Perspectives − Data DBrief: Jobs report, productivity, and inflation expectations by its US team of analysts. They still anticipate “robust hiring” by employers over the coming months as recovery continues (and more reopened schools and childcare facilities mean fewer workers are housebound) but believe the April data means that the US Federal Reserve will hold off on debating when to begin tapering its monetary stimulus programme.

“With the economy still 8.2 million jobs below pre-Covid levels, and with the extrapolation of recent trends indicating that the shortfall from pre-Covid trends would not be closed until beyond 2022 [see Figure 2] it is difficult to see the economy meeting [Fed chairman Jerome] Powell's desire to see “a string” of strong data by the June Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting,” the team notes.

The data also reinforces their expectation that the earliest for the Fed’s leadership to be confident that the US economy has progressed in its recovery enough to signal a clearer review on the tapering timeline is the Jackson Hole Economic Symposium8 in late August.

Figure 2: Recent trends would not return the US labour market to pre-Covid trend even through early 2023

Note: 524k and 294k are the three- and six-month averages on payrolls, and 916k was the first reading on March payrolls.

Source : BLS, Haver Analytics, Deutsche Bank

A benefits disincentive?

The US April non-farm payroll data says much about the bumpiness of the US labour market recovery and an extraordinary reallocation of resources resulting from the pandemic, The Economist suggested (7 May).9 Employers might struggle to forecast demand and quickly find workers to fill it – an example being the recent report that Delta Air Lines had to cancel 100 flights due to a lack of staff.10

Despite the stimulus cheques and a temporary boost of US$300 a week11 in unemployment insurance, the magazine doubts that over-generous benefits explain the shortages. “Though economic research has long concluded that more generous benefits blunt incentives to look for work, this relationship appears to have weakened during the pandemic,” the paper explained. “Workers think twice about turning down a job”.

Instead, it cites two other factors. The first is fear of infection and a government survey found that although the number of people who said they were not seeking work fell by 900,000 in April, it still totalled 2.8 million. Industries experiencing the most acute labour shortages – healthcare, recreation and hospitality – all require much person-to-person contact.

The second is a mismatch between the unemployed and the jobs on offer. “The headline growth in vacancies represents the rise in opportunities in some industries – say, clerks in DIY stores – as others decline,” the paper comments. “An out-of-work bartender in Manhattan may take time to spot and secure a job as a delivery driver in farther-out Westchester. As the economy adjusts to shifting consumer demands, the labour market’s recovery will not always be smooth”.

However, unlike The Economist, the US Chamber of Commerce12 clearly believes that benefits are overly generous. “The disappointing jobs report makes it clear that paying people not to work is dampening what should be a stronger jobs market,” was its response to the latest data.

The governors of South Carolina and Montana have both cited federal unemployment benefits as the cause of local labour shortages and are eliminating them in their states. Defending the move, South Carolina Department of Employment and Workforce director Dan Ellzey said that the state had no less than 81,684 open positions and its hotel and food-service sectors had employee shortages that threatened their sustainability.

“While the federal funds supported our unemployed workers during the peak of Covid-19, we fully agree that reemployment is the best recovery plan for South Carolinians and the economic health of the state,” he added.

A recent Reuters analysis13 also questioned the achievability of the Federal Reserve’s pledge to help restore the US economy to “maximum employment”, by which it means the pre-pandemic position (US unemployment stood at only 3.5% in February 2020[ii]). It added that “early evidence from the reopening of the economy suggests the push to reach that goal may be elusive, or at best a more drawn-out process, as the labour market shifts away from the types of jobs lost in 2020, is potentially further transformed by massive infrastructure spending, and sees some workers quit job-seeking altogether”.

A boost for productivity

Deutsche Bank’s US Chief Economist, Matt Luzzetti and his team recorded in their 7 May report that within the US leisure and hospitality sector, wage growth for production and non-supervisory workers rose by a record 2.7% month-on-month in April. Over the past three months, wages for this group have risen by more than 25% on an annualised basis despite the sector’s strong job growth.

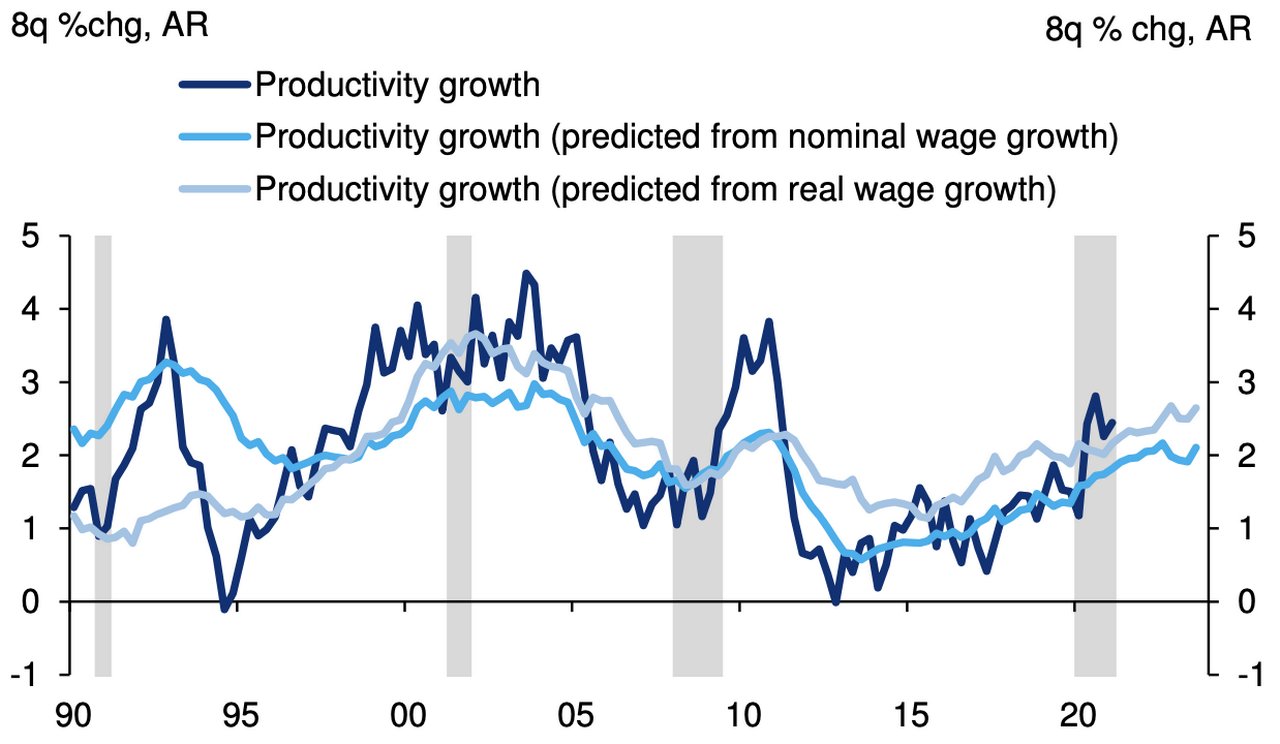

There is an upside from the “surprisingly strong wage growth during the pandemic” however. Luzzetti and colleagues cite “compelling evidence that wage growth leads productivity gains, as tight labour markets and more expensive labour incentivise businesses to undertake productivity-enhancing investments”. As illustrated in Figure 3, they believe that the strength of recent productivity data could extend over the next two years.

Figure 3: Firmer wages point to higher US trend productivity growth

Source: BLS, Haver Analytics, Deutsche Bank

EU skills surpluses and shortages

On the other side of the Atlantic, under Article 30 of the EURES Regulation (EU) 2016/5891, EU Member States are required to “collect and analyse gender-disaggregated information on: (a) labour shortages and labour surpluses on national and sectoral labour markets, paying particular attention to the most vulnerable groups in the labour market and the regions most affected by unemployment; (b) EURES activities at national and, where appropriate, cross-border level”.

The resulting report from the European Commission covering 2019 to 2020 – and the early months in which the European labour market was strongly impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic – includes preliminary analyses of the impact of that pandemic on skill shortages.15 As in other economics, many of the worker shortages are concentrated in the construction and healthcare sectors (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: Most widespread shortage and surplus occupations in 2020

Source: Analyses of data submitted by EURES National Coordination Offices

A further shared trait is that shortages identified in some occupations (e.g. software) continue a trend apparent in previous studies and are nothing new, but the latest report underlines how the extent, severity and persistence of skills shortages in the European workforce reflect “the travel restrictions imposed in many countries/regions to curtail the spread of the virus”. It also highlights how the three skills groups which are strongly represented among the most widespread and severe shortage occupations are “professional healthcare workers, professional IT workers and construction craft workers.”

Outlook for labour

"Finding qualified employees remains the biggest challenge for small businesses and is slowing economic growth"

The job retention programmes to help keep workers employed and save viable jobs have played a vital role in putting economies in a better position to prepare for recovery than they would otherwise have been. As summarised by the OECD, these have included, “measures that directly subsidise hours not worked, such as Germany’s Kurzarbeit or France’s Activité partielle, as well as measures that also top up the earnings of workers on reduced hours, such as The Netherland’s NOW (Noodmatregel Overbrugging Werkgelegenheid) or the Job Keeper Payment in Australia”. 16

With around 60 million people across the OECD having been included in company claims for these programmes, many regions are at an inflection point as nations return to work. Employers will need to tackle reluctance to return with flexibility, and invest in training and skills building to be in the best position to move forward. And as many have already recognised, working from home at least one day a week will be a permanent feature for millions of employees.

Deutsche Bank Research reports referenced

Early Morning Reid - Macro Strategy by Jim Reid (10 May)

Cross-Discipline Thematic Research: DB CoTD: Help! We can't find help by Jim Reid and Raj Bhattacharyya (6 May)

US Economic Perspectives - Data DBrief: Jobs report, productivity, and inflation expectations by Matthew Luzzetti, Brett Ryan, Justin Weidner and Amy Yang (7 May)

Sources

1 See https://bit.ly/3tGpxAj at intereconomics.eu

2 See https://reut.rs/3uG6vuV at reuters.com

3 See https://bit.ly/3w4ZtAp at oecd-ilibrary.org

4 Early Morning Reid, 10 May

5 DB CoTD: Help! We can't find help (Deutsche Bank Research, 6 May 2021)

6 See https://bit.ly/2Q9v58u at flow.db.com

7 See https://www.bls.gov/ at bls.gov

8 See https://bit.ly/3vXmNzW at kansascityfed.org

9 See https://econ.st/3tA1jYg at economist.com

10 See https://bit.ly/3y4Ob0C at aerospace-technology.com

11 See https://bit.ly/3y2UF05 at forbes.com

12 See https://on.mktw.net/3fgSgGJ at marketwatch.com

13 See https://reut.rs/33z8kho at reuters.com

14 See https://bit.ly/33BOX7n at bls.gov

15 See https://bit.ly/3hpaUi7 at op.europa.eu

16 See https://bit.ly/3o7ioI2 at oecd.org

Go to Corporate Bank EXPLORE MORE

Find out more about products and services

Go to Corporate Bank Go to Corporate BankStay up-to-date with

Sign-up flow newsbites

Choose your preferred banking topics and we will send you updated emails based on your selection

Sign-up Sign-upYou might be interested in

MACRO AND MARKETS

Inflation genie drivers Inflation genie drivers

Once post-Covid economic growth accelerates, will inflation spiral out of control? flow’s Graham Buck examines current measures and past performances for indicators

Macro and Markets

America’s US1.9trn kick start America’s US$1.9trn kick start

Despite some late nips and tucks to ensure its safe passage, President Biden’s US$1.9trn American Rescue Bill is an ambitious package whose remit goes beyond reviving the US economy post-Covid-19. flow’s Graham Buck and Clarissa Dann examine what this means for US GDP growth

Macro and markets, Trade finance and lending {icon-book}

Italy’s mighty mid-caps Italy’s mighty mid-caps

Thanks to the European policy response to Covid-19, Italy moved from economic headwinds to tailwinds. But can it stand on its own feet? flow shares some perspectives on Italy’s prospects for growth and its thriving corporate sector