08 April 2020

After a 76-day lockdown, Wuhan in China’s Hubei Province is back in business. flow’s Clarissa Dann takes a closer look at how the pandemic has impacted Asia and how economies are balancing containment, their economies and civil liberties

With reported cases of Covid-19 heading towards the 1.5 million mark globally, and governments balancing virus containment and public health with economic health and the costs of business shutdown, the differences between developed and emerging, Western and Eastern economies in managing this pandemic have become more pronounced.

As the Deutsche Bank Research team note in their 30 March report, Impact of Covid-19 on the global economy: Beyond the abyss, “The timing and shape of the recovery will be determined by several factors, including: (1) the course of the pandemic and effectiveness of efforts to contain it; 2) the depth of the initial decline in activity; and (3) the magnitude, timing, and effectiveness of macro policy responses.”

Regional recession

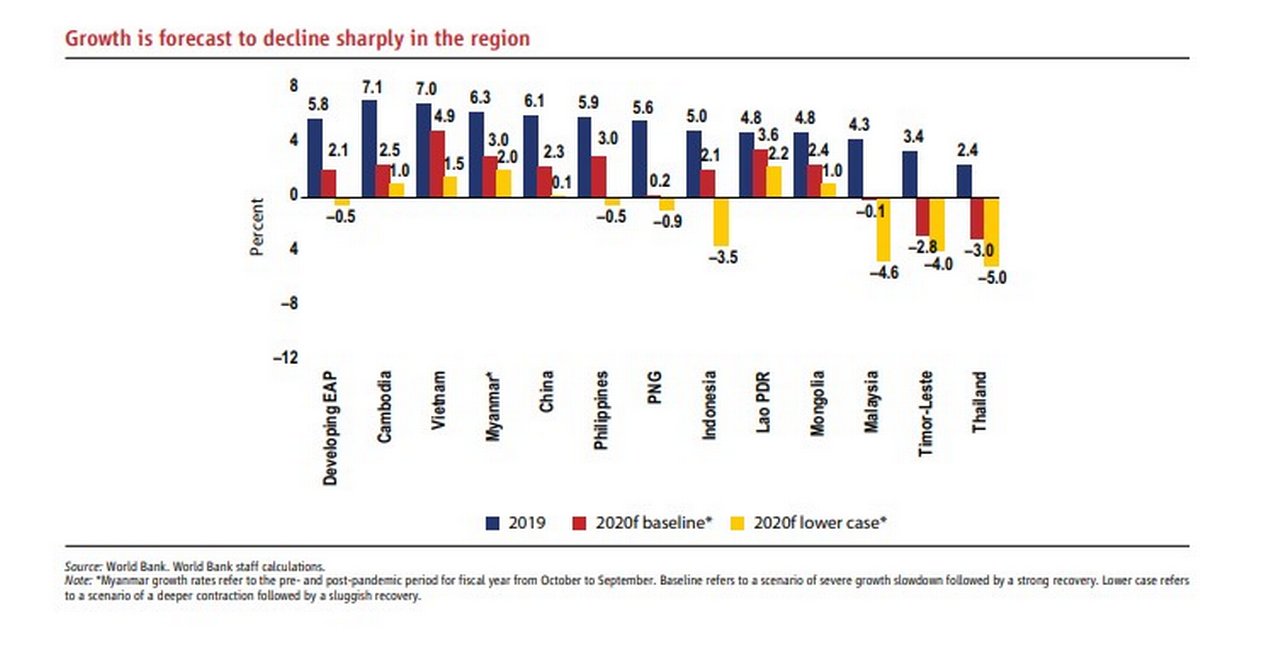

These factors are demonstrated when reviewing Asia’s recovery trajectory – albeit from an earlier start and with some member countries in better economic shape than others. In addition, Asia is the fastest-growing economic region as well as the largest continental economy by both nominal GDP (US$51.58trn) and PPP (US$64.44trn) in the world. But it also is home to almost half the world’s poorest people, according to World Bank estimates. The multilateral development bank warns that as many as 11 million additional people face the prospect of being driven into poverty in East Asia and the Pacific unless urgent action is taken to alleviate the economic impact of Covid-19.

Figure 1: Forecast regional contraction

In its report East Asia and Pacific in the time of Covid-19, (April 2020) the World Bank Group sets out how the region’s relative resilience, demonstrated during recent crises, “is being tested again” and notes “unusual combination of disruptive and mutually reinforcing events”. According to the report’s authors “Significant economic pain seems unavoidable in all countries and the risk of financial instability is high, especially in countries with excessive indebtedness”. Most vulnerable are countries with poor disease control and prevention systems; a heavy dependence on trade, tourism, and commodities; a debt load burden; and that rely on volatile financial flows, they add.

“In Asia, we expect the recession to be the most severe at least since the Asian Financial Crisis,” say the Asia Deutsche Bank Research team in their Asia Economic Notes: The policy response of 6 April. The report follows India’s implementation of a national lockdown on 25 March and the attempt of Malaysia and the Philippines to lock down most, if not all of their populations. Memories of the region’s financial crisis two decades ago are still pretty raw – the International Monetary Fund bail-out in 1997−8 replenished foreign exchange reserves in the central banks of Indonesia, South Korea and Thailand to stabilise exchange rates and reverse the outflow of foreign capital alongside its imposition of structural reforms to maintain macroeconomic stability.

Turning to Covid-19 policy responses in 2020 Asia; while these began with central banks cutting interest rates (they had more to work with as rates were higher than those in the G3 economies), the Deutsche Bank Research team do not see these going much lower because of destabilisation concerns. “In a climate of investor risk aversion, Asian central banks face a trade-off between lower interest rates and weaker currencies,” they reflect. “The need to maintain foreign investor interest constrains monetary policy.”

"In a climate of investor risk aversion, Asian central banks face a trade-off between lower interest rates and weaker currencies"

Capital flight and dollar appreciation

Both the scale of the epidemic and the speed of its global spread have made the Covid-19 economic shock different from past crises, and have unsurprisingly led to large foreign exchange moves. In their paper, The dollar and international capital flows in the Covid-19 crisis, economics academics Giancarlo Corsetti and Emile Marin explain that while the scale of the dollar appreciation to date is not as large as that in 2007, the associated capital flows from emerging markets, week on week “are many times larger than at the peak of the Global Financial Crisis”. They also point out that as of the end of March 2020 nearly 80 countries are requesting IMF help and that the Fund has confirmed US$83bn has left it since the start of the crisis.

The extreme risk-off environment of the past six weeks and the policy response have, observe Deutsche Bank Research in Asia Economic Notes: The Policy Response (6 April), seen some very large moves in Asian currencies against the US dollar “as a consequence of record capital outflows”. While they confirm that markets have “settled down” they do not expect risk appetite to return “until the US is on the other side of the epidemic curve and beginning to go back to work”.

Corsetti and Marin anticipate further pressure on the dollar to appreciate in the near future and also point out that as many emerging markets are central to the global production network, policy action to sustain supply chains and demand for commodities (such as food) will be crucial in helping many contain the economic disruption.

Recovery trajectories

What will an Asian recovery look like? In our article, Light at the end of the tunnel (28 March), flow shared some of Deutsche Bank analyst Yi Xiong’s insights of how China had already arrived at the cusp of a return-to-work status – it tracked and traced the infections.

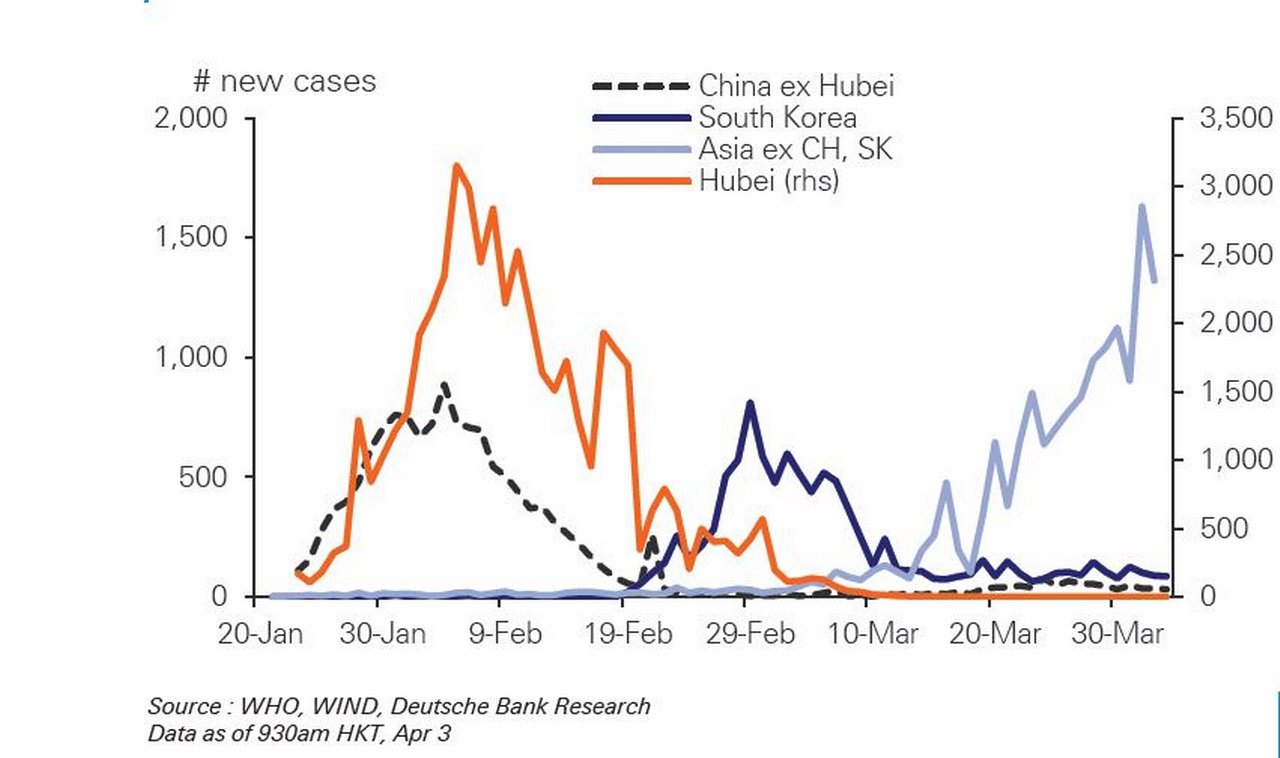

While China seems to have successfully contained the outbreak, albeit at a significant cost of more than 10% of GDP in lost activity, the Asia Economic Notes: The policy response (6 April) research points out how local transmissions of the virus have also been “reasonably well contained” in Hong Kong, Japan, Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan, whereas countries in South and South-East Asia have only just begun to confront the virus (see Figure 2).

In its April report, the World Bank points to how South Korea’s rapid response with testing was able to lower the transmission rate and contain the virus, without the need to resort to the more restrictive social distancing measures. “The Korean government has largely avoided restricting the movement of people, and international borders have remained relatively open to travellers from affected countries,” the authors note.

Figure 2: Covid-19 cases in Asia

Were it not for the contagion elsewhere in the world drying up export orders, normalisation was on track to return around two months after the near-total lockdown in Hubei, reflect the Deutsche Bank analysts, a city now celebrating its opening up (see Figure 2). “The return to work will be slower against a backdrop of vanishing export orders than it would have been had the outbreak been felt simultaneously around the world,” they predict.

Data solutions

While mainland China, South Korea, Hong Kong, Singapore and Taiwan have business as usual in their sights, these Asian countries, notes The Economist, face the same challenge – namely that of how to limit the “all-but-inevitable rise in cases that will follow when they relax current controls”.

In the briefing “The pandemic and the state” (28 March), the newspaper reports on how locked- down households and businesses are using technology “in all sorts of quotidian ways, from video conferencing to team working”. This provides, it adds, “a network of sensors that can co-ordinate the response of both individuals and whole populations to a degree unimaginable in any previous pandemic”.

But given the prospect of extended lockdowns, adoption of data-yielding apps to solve the containment problem seems to be catching on. Since the independent decisions of individuals is the key to sustained containment, it’s important to provide reliable information on which they can base those decisions, explain the authors of the Deutsche Bank report, Asia Notes: How Asia fights the virus (24 March).

They explain how the three-week delay in providing such data in China “cost the government a lot of credibility and it certainly allowed hundreds if not thousands of people to become infected that might not otherwise have been”. However, “they soon made up for it by releasing detailed information about cases – especially outside Hubei where the numbers are lower.”

The analysts explain how tracing contacts from Wuhan at one point had the Chinese government deploying 1,800 teams of more than five people each following up on tens of thousands of contacts every day. Quickly, this was supported by data from telecom companies and software providers. Geolocation data was used – and made available to the authorities – to assist in identifying people’s travel histories. This was further supplemented with information on recent bus, plane or train ticket purchase and seat locations relative to travellers with confirmed cases.

The South Korean government also includes credit card usage information and requires people arriving from abroad to download an app onto their phones which they use to monitor their health and location. This can also be used to identify people who have violated quarantine.

Information technology has, to a certain extent, offered a solution with governments partnering with private sector providers. It provides the means of disseminating the information about the risks of infection to individuals, who can then choose for themselves how much distance to keep from others.

While the authorities in Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan have published daily updates since early January on confirmed infections, treatments and deaths, the case numbers are much smaller and this makes it possible to provide much more information. Each case is described with detailed locations, identifiers (not names, of course but often places of residence), and travel history and, where known, how they relate to other cases. The data is uploaded onto government websites with places of residence located on maps so that people can assess their own risk of infection.

"TraceTogether tracks when you are in close proximity with these other persons, including timestamps"

Singapore’s introduction of its new app TraceTogether alerts users if they have been in close proximity with a confirmed case of Covid-19. Using Bluetooth, the app identifies other nearby phones with the app installed. “It then tracks when you are in close proximity with these other persons, including timestamps,” explains the government website. If the need arises, this information can then be used to identify close contacts based on the proximity and duration of an encounter between the two users.” The site reassures users that the app does not track location or contacts, that data is stored for only 21 days and not accessed unless the user is identified as a close contact, and that measures are in place to protect the user’s mobile number using a random ID system.

Tiger feet

With other economies still some way behind China in terms of their Covid-19 journeys, it seems fitting to close with the comments of Deutsche Bank’s Global Head of Economic Research, Peter Hooper and Thematic Research Analyst Luke Templeman in the 6 April Podzept podcast, Beyond the Abyss.

“China experienced the virus and the economic damage first,” said Templeman. And while economic activity declined at a record pace during the height of the crisis, this was not a total lockdown of the Chinese economy. Hooper explained, “The restrictions on Wuhan have been lifted, so the experience in China has been that the period of greatest social distancing lasted about a month and they were on track to fully reopen businesses the following two months.” On this basis, he predicted a “robust” recovery to 6.5% GDP growth for Q2, with the caveat, that will be “slowed down by the recession in the US and Europe which we are now dealing with”.

In other words, China cannot completely recover from its ill health until the other two major economies are in recovery. What that means for containment, tracking and testing remains to be seen.

Summary of Deutsche Bank Research reports referenced

Impact of Covid-19 on the global economy: Beyond the abyss (30 March 2020) by David Folkerts-Landau, Peter Hooper, Mark Wall, Matthew Luzzetti, Michael Spencer, Stefan Schneider, Yi Xiong, Kentaro Koyama, Torsten Sløk, Juliana Lee, Binky Chadha, Jim Reid, Francis Yared, George Saravelos, Justin Weidner, Surav Dasgupta, and Kuhumita Bhattacharya

Asia Economic Notes: The policy response (6 April 2020) by Juliana Lee; Michael Spencer, Kaushik Das, Vaninder Singh; and Yi Xiong

Asia Economic Notes: How Asia fight the virus (24 March 2020) by Michael Spencer, Juliana Lee and Yi Xiong

Podzept: Beyond the Abyss (6 April). A podcast with Luke Templeman and Peter Hooper

Deutsche Bank clients can access the full research reports here

If you would like access do contact a Deutsche Bank sales representative

Go to Corporate Bank EXPLORE MORE

Find out more about products and services

Go to Corporate Bank Go to Corporate BankStay up-to-date with

Sign-up flow newsbites

Choose your preferred banking topics and we will send you updated emails based on your selection

Sign-up Sign-upSubscribe Subscribe to our magazine

flow magazine is published published annually and can be read online and delivered to your door in print

YOU MIGHT BE INTERESTED IN

MACRO AND MARKETS, CASH MANAGEMENT, TRADE FINANCE

Towards a silver lining Towards a silver lining

While the Covid-19 pandemic extends its grip, analysts are already assessing the impact and cost of what could be around US$5trn in fiscal support, and economies taking lessons from the global financial crisis

MACRO AND MARKETS, TRADE FINANCE, CASH MANAGEMENT

End of the tunnel End of the tunnel

With light at the end of the Covid-19 tunnel nearer for some regions than others, flow’s Clarissa Dann examines the pandemic’s economic impact and responses as households and firms plan for the eventual recovery

MACRO AND MARKETS, CASH MANAGEMENT, TRADE FINANCE

Coping with Covid-19 Coping with Covid-19

With the coronavirus now pronounced a pandemic by the World Health Organisation and lockdown imposed on more regions and cities, what will be the impact on the global economy? flow reviews extracts from Deutsche Bank research