June 2020

As India grapples with Covid-19, how ready will the country be to achieve its potential once the pandemic is over? Clarissa Dann reviews its post-independence growth and measures taken to improve the ease of doing business

When India’s Finance Minister, Nirmala Sitharaman, tabled her Union Budget on 1 February 2020, she declared: “We are now the fifth-largest economy of the world. India’s foreign direct investment got elevated to the level of US$284bn during 2014−19 from US$190bn that came in during the years 2009−14. The Central Government debt that has been the bane of our economy got reduced, in March 2019, to 48.7% of GDP from a level of 52.2% in March 2014.”1

She added: “Between 2006−16, India was able to raise 271 million people out of poverty, which we all should be proud of.” India’s ambition to become a US$5trn economy by the mid-2020s through wealth creation and improved ease of doing business is enshrined in the Economic Survey 2019−2020, published on the Ministry of Finance website.2

However, Sitharaman’s remarks were made more than six weeks before Prime Minister Narendra Modi locked down the country’s 1.349 billion citizens, a quarter of whom live below the poverty line, for 54 days, from 25 March to 17 May 2020, in an attempt to contain the spread of Covid-19. Modi pointed out that the lockdown was necessary to slow the spread of the virus, and a US$22.6bn fiscal relief package (around 0.8% of India’s GDP) was announced a day later. “The unprecedented lockdown has stung millions of poor in the world’s second most populous country, leaving many hungry and forcing jobless migrant labourers to flee cities and walk hundreds of kilometres to their native villages,” reported Al Jazeera on 29 March.3

How will India recover from this economic shock? “Even in the pre-lockdown stage, India’s economic momentum remained significantly weak compared to its potential, with a negative output gap of 2−2.5%,” noted Deutsche Bank’s Chief Economist for India, Kaushik Das, on 24 March 2020. Das believes monetary stimulus may have to “move far beyond traditional rate cuts to provide support to the economy”. He adds, “Also, it is worth noting that the services sector in India contributes more than 60% to overall GDP; therefore the damage to the overall growth dynamic arising out of the 54-day nationwide lockdown is expected to be substantial.” This article takes a look at India’s longer-term potential beyond this current external shock, and at its underlying fundamentals.

Infrastructure uplift

With strengthening of India’s supply chain infrastructure gaining momentum from five years of significant investment on roads, railways, water, irrigation and urban projects, the next five years will, according to Reuters’ reports on Sitharaman’s announcements, see further funding of INR100trn (US$1.39trn) in the sector.4

The World Bank maintains that “India’s ability to achieve rapid, sustainable development will have profound implications for the world” and its success “will be central to the world’s collective ambition of ending extreme poverty and promoting shared prosperity, as well as for achieving the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals”.5

“In past decades, India has never managed to work at its full potential, yet we have a large young population ready to go, we have good natural resources and entrepreneurship, and we have some long-term enabling work done by the government,” reflects Mumbai-based Kaushik Shaparia, Deutsche Bank’s Chief Country Officer in India. He believes that even if the government only achieves a third of its planned US$1.4trn infrastructure investment in the next five years, “this will still go a long way”.

Foreign investment and capitalisation

A turning point was 1991, when US$2.2bn of emergency assistance from the International Monetary Fund came with certain conditions attached: the country had to open up to foreign investment, cut red tape and remove trade barriers.6 “Many saw this as the start of India’s reintegration into the global economy, and over the last 20 years liberalisation has connected its young, vibrant workforce with firms around the world,” noted the BBC in April 2019, as 900 million Indian citizens prepared to vote in the general elections held over five weeks. Today, its business reporter added, India is one of the world’s top outsourcing destinations, with many of its workers powering back-end IT systems, call centres and software development.7

Levels of foreign direct investment (FDI) have risen in line with investor optimism about India’s economy; the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development posted US$49bn of FDI inflows for 2019, with most of them bound for the service and information technology industries.8 “The opening up of FDI has given a fair amount of opportunity to overseas investors,” says Shaparia. He adds that, in 2019, Deutsche Bank put €450m into India, bringing the total capital invested to more than €2bn. This made it the fourth-largest foreign bank in the country, with securities services as one of the bank’s strongest Indian businesses. Assets under custody for December 2019 topped €267bn, with 57% pertaining to cross-border clients and the remaining 43% to domestic clients.

With investor appetite at this level, Deutsche Bank is well placed to structure deals and sell down participation to like-minded investors, Shaparia explains. However, he notes, “In the short term we have to be careful if things don’t move fast, which means watching exposures while not losing out.”

Trade trends

India decided in November 2019 to opt out of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) after seven years of negotiations, citing inadequate safeguards to protect Indian farmers. However, some observers believe there is a strong case for India getting back into the RCEP. Why? Because manufactured goods once imported from China are now being produced in Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) country locations. If India does not have free trade agreements with those countries “then we will be stuck with high import costs”, said Shailesh Haribhakti, a Mumbai-based independent non-executive director and chartered accountant, at GTR India 2020.9 Noting that India’s share of global export volumes is just 1.67%, reflecting “decades of insularity” following independence in 1947, he advocates staying away from protectionism.

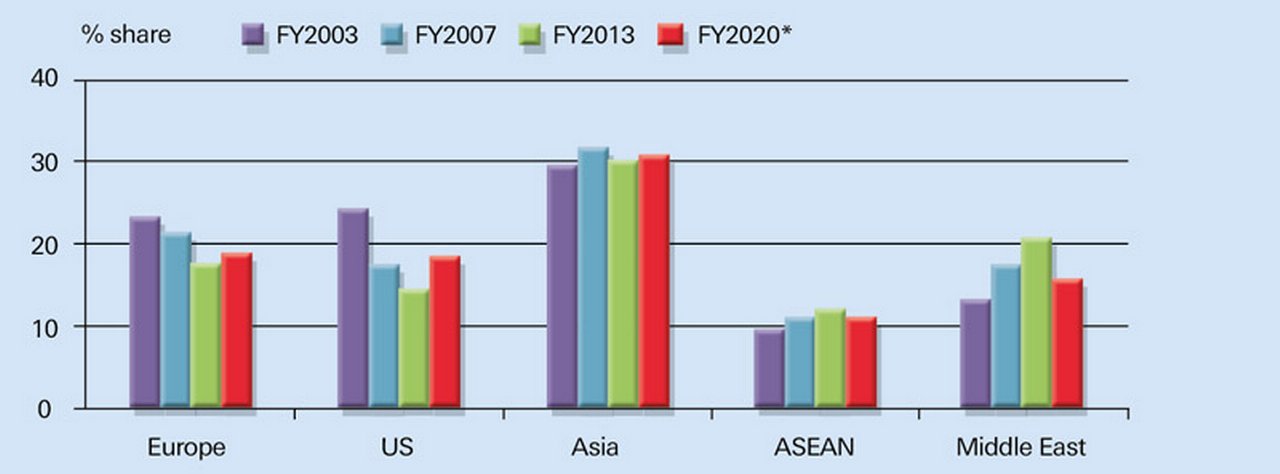

Deutsche Bank’s Kaushik Das points out that Asian countries (including ASEAN and the Middle East) now account for almost 47% of India’s exports, up from around 39% in 2001, with shares of exports to North America and Europe forecast to dip in 2020 to 19% and 19.4% respectively (see Figure 1, below).

Figure 1: India’s exports by region

Source: CEIC, Ministry of Commerce, Deutsche Bank Research

*FY2020 data refers to April 2019 to January 2020

Das explains that a quick look at India’s top 10 items for export shows that five key categories − engineering goods, petroleum products, gems and jewellery, chemicals, and drugs and pharmaceuticals − account for almost 65% of total exports, with the US and China being India’s key export destinations. India’s key imports include crude oil, electronic goods, machinery, gold and coal. Some of these are used as intermediary products for re-export, while others are used as finished goods for capital-intensive investment in the domestic economy. Again, China and the US are the key countries from which India imports.

Another measure that could help raise India’s export output is the increased support for its export credit agency (ECA), Export-Import Bank of India (EXIM Bank) – one of the largest bond issuers on India’s stock exchange, India INX. In January 2020, it raised US$1bn under its US$10bn mediumterm note programme established on the Global Securities Market Index on India INX. It has already listed US$5.6bn bonds under the programme. EXIM Bank lends for exports from India, including supporting overseas buyers and Indian suppliers for exports of developmental and infrastructure projects, equipment and goods from India. Post Covid-19 this ECA, along with others around the world, will be a critical force in helping India rebuild its trade corridors.

"We have a large young population ready to go, and we have good natural resources and entrepreneurship"

Digitalisation

Although India set about its digitalisation journey somewhat later than other Asian advanced economies, there has been a determined push since the first main initiative in 2014. This saw the launch of the Unique Identification Authority of India, whose role was to assign every one of the country’s 1.2 billion citizens an Aadhaar – a 12-digit unique identification number based on biometric and demographic data connected to the individual’s mobile phone and bank account.

Another area of focus is India’s ports and terminals (private and public) as an opportunity for productivity improvement. The government launched the Port Community System, a digital collaboration platform known as PCS 1x, in December 2018. With 15,874 registered users by March 2020, this connects marine terminals, transport service providers such as shipping lines, freight forwarders, haulage companies and freight rail networks, and related intermediaries such as customs brokers. PCS 1x makes it possible to electronically process delivery orders, transport orders and delivery gate schedules, and to track containers.

In an effort to improve connectivity for banks, the Reserve Bank of India developed the Export Data Processing and Monitoring System. Launched in 2014, this streamlines the flow of export data, capturing information relating to shipping bills issued by customs and enabling banks to report realisation and settlement of these shipping bills against inward remittance received by their clients. This, in turn, enhances the tracking and monitoring mechanism of cross-border trade and reduces the flow of data. Its internal equivalent, the Internal Data Processing and Monitoring System, followed in 2016. This has been cited as an example of improved foreign trade operations achieved by India, and as a contributor to the country’s improved score in the World Bank’s Doing Business index (India rose 14 places to 63rd out of 190 nations in the 2020 index). However, it puts responsibility on the banks – importers and exporters do not have access to the system.

India’s ‘smart cities’

Launched in 2015, India’s Smart Cities Mission is administered by the government’s Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs. Its objective is to promote cities that provide core infrastructure (such as adequate water and power supplies, sanitation and waste management, urban mobility and public transport) and “give a decent quality of life to its citizens, [and] a clean and sustainable environment”, thus acting as a beacon to inspire other cities.

Initially, state governments nominated cities to take part in the scheme and the administrative bodies of those cities were then asked to submit ‘smart city’ plans for urban renewal. One hundred cities were chosen to receive funding to implement their plans and the deadline for project completion was set between 2019 and 2023. In September 2019, the 10,000-acre Aurangabad Industrial City was inaugurated as the first smart city.

In addition, the scheme has promoted cooperation between the EU and India. A Joint Action Plan announced in New Delhi on 19 September 2019 to step this up stated that the next phase of implementation would see further cooperation between the two regions, with the European Investment Bank aiming to invest €1bn in urban transport to follow existing metro projects of €1.6bn in India.10 In 2016, the Obama administration in the US signed memorandums of understanding to develop three smart cities in Allahabad, Ajmer and Visakhapatnam, providing project planning, infrastructure development, feasibility studies and capacity building.11

Regulatory changes

India’s Goods and Services Tax (GST) reform has been in place since July 2017 and e-invoicing became mandatory as at 1 April 2020 in a bid to improve transactional transparency and reduce tax evasion. No country of the size of India has attempted tax reform of this magnitude. Goods and services not rated zero are now taxed under four basic rates: 5%, 12%, 18% and 28%.

The reform was hailed as a success by the Confederation of Indian Industry. “GST is not just a tax change but a business change. It impacted business processes and businesses needed support from government for this change,” said its Director General, Chandrajit Banerjee. “And government did that well – it reached out to industry through training by its officers across the country. Indian industry was also really flexible in its approach and that helped in the successful roll out of GST.”12

In an e-invoicing environment, the moment an invoice is created, it has to be uploaded onto the Goods and Services Tax Network portal for pre-validation and assignment of an invoice reference number. Once this is issued, the tax invoice is shared with the recipient. At the time of writing, given the business interruption caused by Covid-19, and the slow take-up of voluntary trials, the Ministry of Finance was considering deferring e-invoicing implementation to July 2020.

Sources

1 See https://bit.ly/2VwBvyz at livemint.com

2 See https://bit.ly/38JpbS5 at indiabudget.gov.in>

3 See https://bit.ly/3eJ88k3 at aljazeera.com

4 See https://reut.rs/2zp35VP at reuters.com

5 See https://bit.ly/3nEkME5 at wolrdbank.org

6 See https://bit.ly/2KsoFed at imf.org

7 See https://bbc.in/2XCYpEq at bbc.com

8 See https://bit.ly/2yBRClg at fdi.finance

9 See Journey into simplicity at flow.db.com

10 See https://bit.ly/3cDW4Pc at eeas.europa.eu

11 See https://bit.ly/3bvAVq9 at economictimes.indiatimes.com

12 See https://bit.ly/2W4ZiVt at cii.in

You might be interested in

CASH MANAGEMENT, TECHNOLOGY

MultiSafepay and “Request to Pay”: open banking comes of age MultiSafepay and “Request to Pay”: open banking comes of age

The implementation of Europe’s second Payment Services Directive (PSD2) has unlocked a number of new open banking solutions, such as Request to Pay (RtP).

Macro and markets, Cash management, Trade finance and lending

Towards a silver lining Towards a silver lining

While the Covid-19 pandemic extends its grip, analysts are already assessing the impact and cost of what could be around US$5trn in fiscal support, and economies taking lessons from the global financial crisis

MACRO AND MARKETS {icon-book}

A Hellenic recovery A Hellenic recovery

After a prolonged bout of austerity, Greece was on track for an economic comeback before Covid-19. flow’s Graham Buck asks whether the pandemic has derailed the recovery, or merely delayed it