September 2020

After a prolonged bout of austerity, Greece was on track for an economic comeback before Covid-19. flow’s Graham Buck asks whether the pandemic has derailed the recovery, or merely delayed it

It’s been 10 years since the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the EU first agreed a financial rescue package for Greece.1 Eight years have elapsed since the term ‘Grexit’ was coined in response to threats that the government debt crisis would trigger withdrawal from both the EU and the single European currency.

After a prolonged bout of austerity, by 2018 Greece appeared to be finally back on the road to economic recovery. In June that year a deal was agreed2 to wean it off financial dependence on other EU member countries and the IMF. “After eight long years, Greece will finally be graduating from its financial assistance,” declared Mário Centeno, president of the Eurogroup of eurozone finance ministers

“Greece has joined Ireland, Spain, Cyprus and Portugal in the ranks of euro-area countries that turned around their economies and once again stand on their own feet.”

A Deutsche Bank Research report issued at that time, Greece: the Last Deal?, noted, “The agreement entails stronger monitoring – by EU authorities and the IMF – and [stronger] conditionality than in previous programme exits. In addition to quarterly ‘enhanced surveillance’ reviews, promises of debt relief and less fiscal pressure will be staggered over time and not granted immediately. The European authorities hope that this will provide the right incentives for Greece to comply with its engagements.”

Pro-business policies

And as the new decade got under way, these hopes appeared to be fulfilled. In April 2020, The Economist reported that this year began with business confidence “at an all-time high”,3 due in part to the election in July 2019 of a pro-business conservative, Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis, a Harvard-educated former banker.

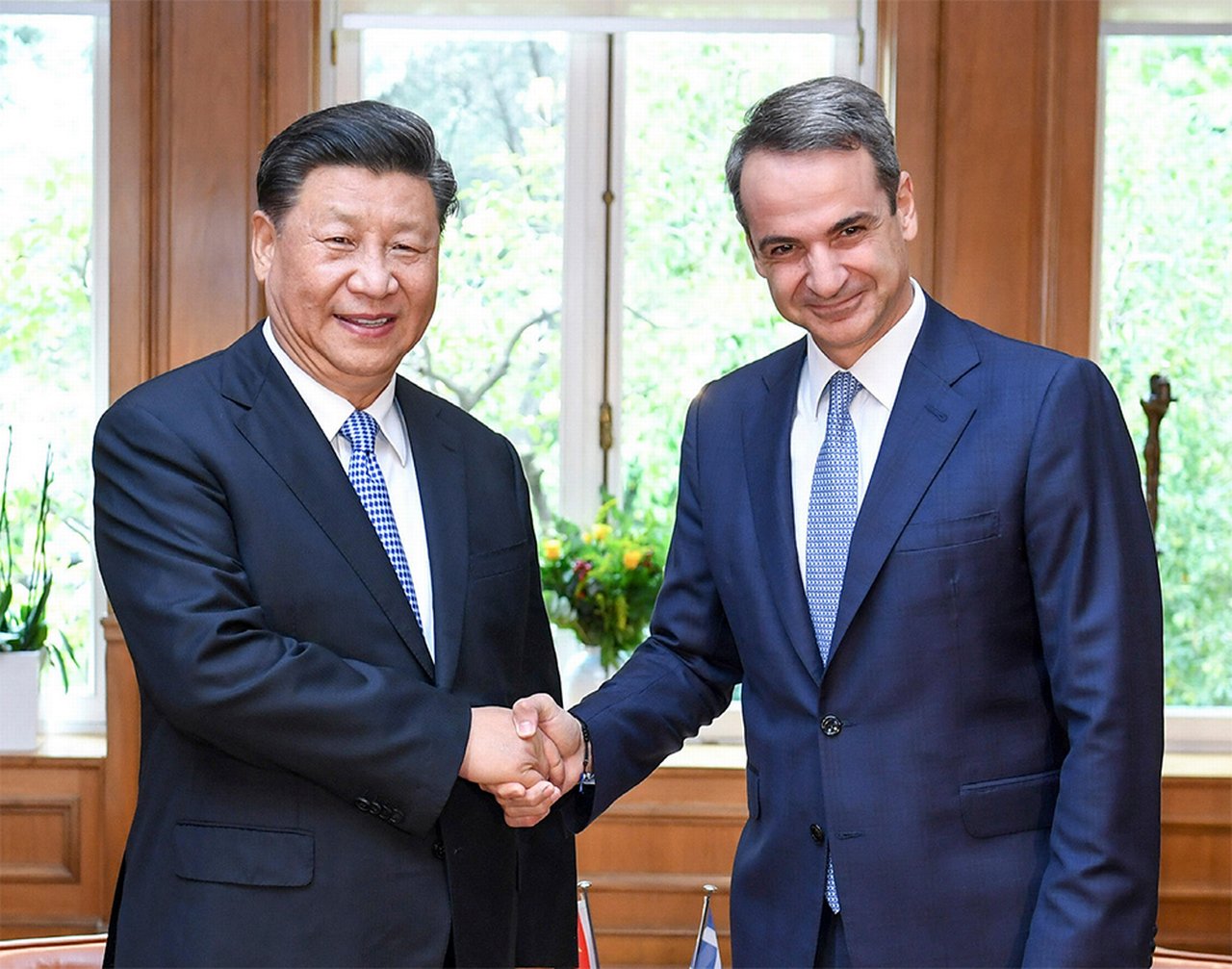

The publication applauded the initial reforms of his incoming New Democracy party, which included cutting Greece’s “labyrinthine red tape” to make starting a new business easier, reforming labour laws to reduce the cost of firing an employee and proposing a reduction from 28% to 24% in the corporate tax rate. In November 2019, Mitsotakis signed off on a €612m investment by China Ocean Shipping Company (COSCO) in Piraeus Port, Athens as part of 16 trade deals agreed between Greece and China. COSCO plans to develop the port into Europe’s biggest commercial harbour. Visiting the company’s head office in Shanghai, the prime minister told China’s president Xi Jinping that his government was “determined to facilitate foreign investors, attract foreign capital and create wealth and prosperity for all Greeks in a way that is sustainable and protects the environment.” The visit was reciprocated, with Xi making an official trip to Athens.

Market capitalisation at the Athens Stock Exchange rose by 47% in 2019, the biggest increase in the world for that year and a personal best for the exchange – although from a low base.4 In 2019, the GDP growth for Greece came in at 1.9%, the same rate as in 2018, and a bullish government was projecting an acceleration to 2.8% for 2020. By April 2020, the unemployment rate had been lowered to 15.5%, against a peak of 27.5% reached back in 2013.

The prospect of continuing improvement disappeared once the impact of Covid-19 became clear. Even before the first reported fatality in Greece on 12 March, all educational institutions had been closed; soon public gatherings were restricted to a maximum of 10 people and the government ordered the closure of all non-essential retail outlets. On 22 March, by which time the country had over 620 confirmed cases of the virus and 15 fatalities, a national lockdown was imposed, which included the country’s hotels.

The actions were effective in limiting the further spread of coronavirus – as of 20 August, the respective figures were 7,934 cases and 235 deaths as the global total neared 23 million cases and 800,000 deaths.

President Xi Jinping held talks with Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis in Athens, November 2019

Safe haven

“It’s clear that Greece has come through the pandemic very well having imposed a lockdown early on, with a relatively low level of coronavirus cases and fatalities,” says Nicholas Exarchos, Deutsche Bank’s Chief Country Officer for Greece, where the branch has been established for 40 years.

"It’s clear that Greece has come through the pandemic very well, having imposed a lockdown early on"

Over this period, the bank has worked very closely with the private sector, banking system, regulators and the government, and it acted as the exchange agent for the landmark €200bn debt exchange in 2012 that kept Greece within the EU. This was the largest debt exchange in history at the time. Additionally, it has assisted the government and the European Stability Mechanism on many occasions in recapitalising Greece’s banks. Most recently, Deutsche Bank has been advising the government regarding the privatisation of Athens International Airport.

“The impact of Covid-19 on the economy will depend on the speed and the extent of any global recovery,” adds Exarchos. “However, tourism accounts for over 25% of Greece’s GDP5 and the season was already well under way by the time borders reopened to most tourists in mid-June. By autumn it will be possible to take stock of the impact.” Potentially the damage will be limited; Greece’s coronavirus statistics compare favourably against those of other popular destinations such as Italy and Spain, thus enabling the country to promote itself as a safe destination for tourists.

Nonetheless, the reliance on tourism also means that the European Commission (EC) expects Greece’s national income to contract by -9.7% in 2020, against -9.5% for Italy and -9.4% for Spain, despite its more favourable Covid-19 statistics. But – barring the possibility that second and subsequent waves of the virus delay recovery – the country is expected to rebound strongly in 2021, with projected growth of 7.9% against 6.5% for Italy and 7% for Spain.

Alexis Patelis, chief economic adviser to the government, is even more bullish and expects the recession triggered by Covid-19 to be less severe than in many other EU member states. “At its core, this is a crisis that tests the ability of governments to deal with unexpected events, with ripple effects on current and future consumer and investor confidence and trust,” he declared at the end of April. As the lockdown measures eased, he subsequently added: “We continue to believe that the more successful a country is in fighting the pandemic, the shorter the economic recession and the stronger the recovery, [and that] hard work, attention to detail, consistency and persistence pay dividends.”

His assessment was shared by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), which was also more upbeat than the EC and IMF in its semiannual report issued in June. This anticipated a less severe drop of -8% in Greece’s GDP this year – only widening to 9.8% in the event a second wave of the virus triggers a double-hit scenario – but also a more modest recovery in 2021 of 4.5%.

“The crisis is hampering loan securitisation activity globally and has delayed steps to resolve banks’ non-performing loan burdens and balance sheet pressures, which will continue to constrain growth in bank lending, even as [European Central Bank] ECB measures keep borrowing costs low,” the OECD reported. “The sale of state-owned enterprises and steps to attract foreign direct investment are likely to be delayed. In the double-hit scenario, these delays will lengthen. Lower activity and income will reduce tax and social contribution payments, shifting the budget from a substantial primary surplus to deficit. Along with the drop in nominal GDP, this will raise public debt ratios.”

€72bn

The EC’s announcement in July of a €750bn recovery fund to assist EU economies hardest hit by the pandemic earmarked €72bn for Greece (with €209bn and €140bn respectively for Italy and Spain). To further mitigate the effects, the ECB agreed to buy Greek government bonds despite their lack of an investment grade rating. The agreement provides Greece with a unique opportunity. “Greece will be one of the largest beneficiaries of the recovery fund in Europe, receiving nearly 20% of GDP in loans and grants over the coming years,” says George Saravelos, Managing Director in Deutsche Bank’s macro research team. “With the right investments, the funds can be transformational for Greece’s productive capacity.”

Figure 1: Greece GDP growth and inflation, 1980–2020

Source: www.imf.org/en/countries/GRC

Hercules to the rescue

Greece’s road to economic recovery was challenging even before the current crisis. The Deutsche Bank report commented that the potential output growth outlook “remains lukewarm”, noting also that the EC 2015 Ageing Report forecasts the country’s working-age population will decrease by 30% (-0.9% year-on-year) between 2020 and 2060. Greece has also experienced a decline in the value of its exports and a shortage of skilled workers following the ‘brain drain’ of recent years. And while progress has been made in addressing the issue of nonperforming loans (NPLs) – Greek banks have worked to reduce their exposure in the past three years – an estimated €75bn burden remains.6 In January, Parliament approved Project Hercules, an asset guarantee scheme to help the country’s banks further deleverage their NPLs without government subsidies being involved.

Against these challenges, Exarchos points to long-term strengths; for example, the shipping industry. Greece has the biggest fleet worldwide and controls 20% of global shipping – which may not always be evident as many Greek-owned ships are registered in other jurisdictions such as Panama, British Virgin Islands, Cyprus and other ‘flag of convenience’ jurisdictions.

And Elizabeth Koskorou, Deutsche Bank’s Head of Corporate Bank and Institutional Cash Greece, reports that Greek banks are ready to embrace digital as a key component for maintaining and growing both revenues and relevance, despite the recent adverse economic conditions. Deutsche Bank is partnering and supporting a number of financial institutions in the country, while the bank’s Athens office also proved its capabilities in the early days of the pandemic;7 for example, by ensuring that payments for much-needed medical supplies went through promptly. In June, it completed a reserve-based lending facility for Energen Corporation to fund its acquisition of the upstream assets of Italy’s Enel.

It has been predicted that regained credibility should allow Greece to reestablish itself in the global capital markets. A further positive was the Switzerland-based Institute for Management Development’s latest annual report on competitiveness, which found that Greece’s competitive position has improved over the past year.

To evidence that its reforming zeal remains unabated, the government marked its first anniversary in July by listing current initiatives. They include a ban on single-use plastics from 1 January 2021, a bill revising the country’s corporate governance framework that includes 25% minimum female representation on the board of directors of listed companies, and the introduction of a 7% flat tax rate on their pensions to attract foreign pensioners. There is reason to believe that while the pandemic will strew obstacles on the road to recovery, it won’t terminate the journey.

Sources

1 See https://bit.ly/2ZPr6ib at imf.org

2 See https://nyti.ms/3iCFtzb at nytimes.com

3 See https://econ.st/3gHYDBZ at economist.com

4 See https://bit.ly/2Z9GQxk at forbes.com

5 See https://bit.ly/3ecXhxp at ekathimerini.com

6 See https://bit.ly/2O88zZi at structuredfinanceinbrief.com

7 See Bank support during Covid-19 at flow.db.com

You might be interested in

MACRO AND MARKETS, COVID-19

World economic outlook: the patient’s progress World economic outlook: the patient’s progress

With a potential five-year trek back to near-normal economic health, the Deutsche Bank Research new World Outlook report has revised upwards projections of three months ago – but much is contingent on good news in 2021 about a vaccine. flow ’s Graham Buck and Clarissa Dann report

CASH MANAGEMENT

Bank support during Covid-19 Bank support during Covid-19

As the Covid-19 pandemic continues its disruption and dislocation of economies, businesses and supply chains, banks are working with governments and their clients to ramp up support initiatives. Here are some examples of Deutsche Bank activity

Macro and markets, Trade finance and lending

No trade, no gain? No trade, no gain?

flow reflects on the seismic changes in the economic world order over the past 12 months, drawing on insights from the Deutsche Bank Research latest Outlook. The focus around inflation and rate cutting remains, centred on the scale of potential US tariffs following the decisive Republican victory on 5 November