1 October 2021

Trade economist Rebecca Harding examines how Covid-induced patterns of shifting work and consumption have increased supply chain scrutiny and highlighted critical export flows

MINUTES min read

Cargo ships are still being unloaded at ports, freight trains and aircraft will always carry goods to landlocked countries, and there are regular reminders that road transport and logistics remain critical to the process of ensuring that supermarket shelves stay well stocked with produce. Nonetheless, trade has changed beyond recognition.

Supply chain dependencies

The disruptions to supply chains since the Covid pandemic began in early 2020 show just how vulnerable this whole system is. Companies and countries began to realise how dependent critical supply chains are on single suppliers or the concentrated resources of one country: as production slowed or stopped temporarily and containers became stranded or mis-located around the world. In March, the Ever Given crisis illustrated how businesses around the world could grind to a halt because one tanker got stuck in a major trade route.1

The shift is not new. Semi-conductor trade has been falling globally since 2014 and trade in critical minerals for electronics has been in decline since 2015, with cobalt dropping sharply in 2019 on a combination of oversupply and waning demand. Each year, the month of October is marked by a spike in the global toy trade but the peak has been reducing year-on-year since 2016, driven by slower exports from China. These are all supply chains that impact our consumption further down the line: cars, electrical equipment and even our leisure activities such as computer gaming.

The US government’s 100-day Supply Chain Review findings announced on 8 June2 defined four supply chains whose resilience it deemed critical in times of emergency:

- Semi-conductors;

- Critical minerals for electronics;

- Electric car batteries; and

- Active ingredients for pharmaceuticals.

The report concluded that resilience in these sectors would enable the US economy to continue through any sudden external shock, such as a pandemic.

Reduced trade in semiconductors and critical mineral fuels

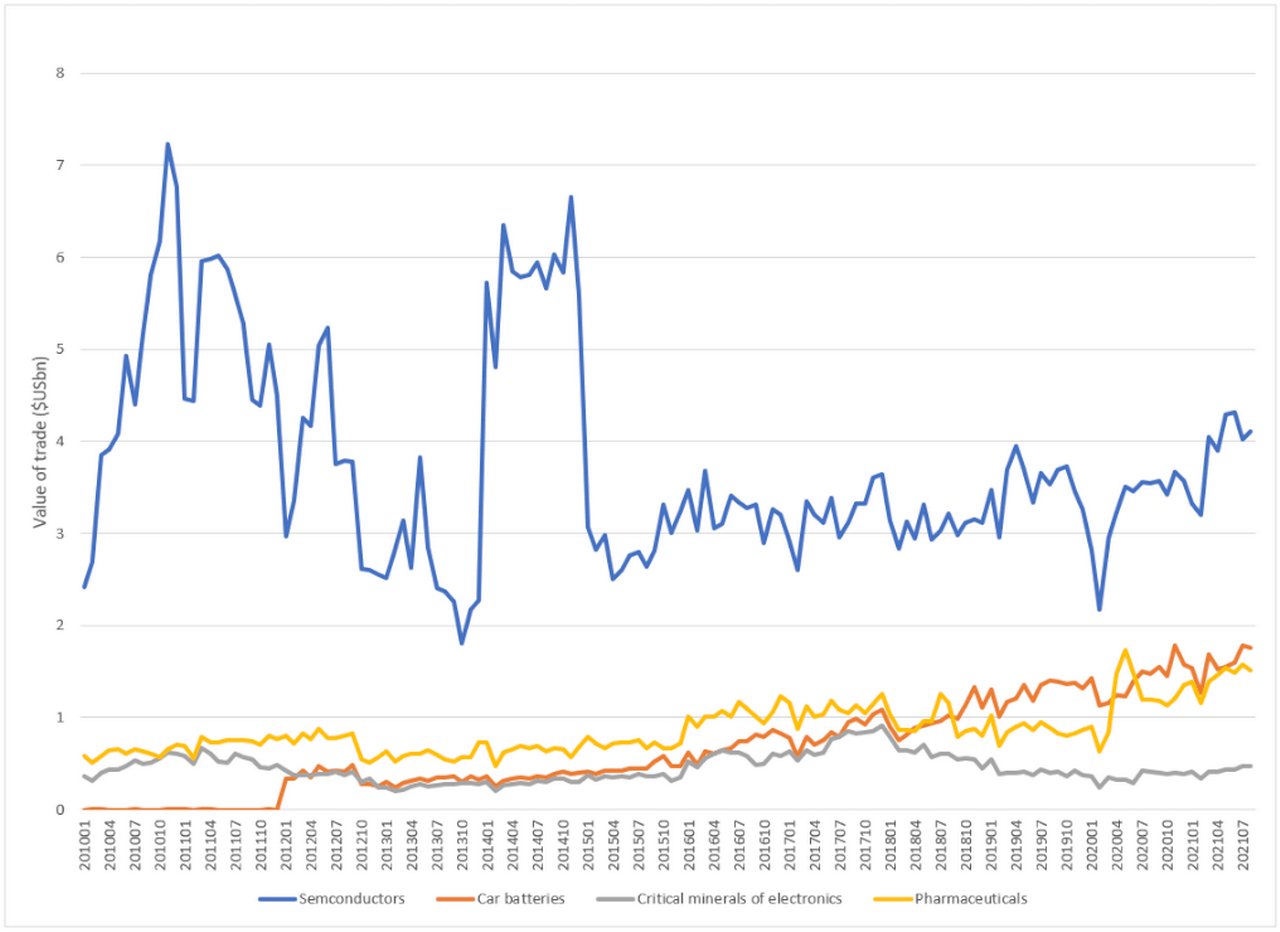

Figure 1: Global critical supply chains as defined by US strategic review 2010−2020 (US$bn)

Source: Coriolis Technologies

The patterns of trade in these four supply chains show that the month-to-month decline in volumes for semiconductors and critical mineral fuels for electronics pre-dates the Covid pandemic. Both have been falling in value terms since 2017, when the threat of tariffs on these products globally started to emerge.

Of more importance, perhaps, is the fact that the chart relates to the value of trade in US dollar terms. But, as St Louis Fed data shows, semi-conductor prices moved downwards over exactly the same period. So while values might be lower, this hasn’t necessarily affected volumes – more is produced, but the prices are cheaper.3 A more recent recovery in value reflects the fact that prices have risen as supplies have become more strained.

Electric car batteries show a pandemic-related dip in the first quarter of 2020, suggesting that this was indeed affected by Covid disruptions. Against this, the supply chain related to active ingredients in pharmaceuticals and medicines increased consistently over the time period in value terms – again suggesting that it was influenced by the pandemic, only positively.

Role of China in these supply chains

A common factor links all these supply chains however: the reasons why they are regarded as vital possibly has much to do with US domestic security – for example to maintain America’s supply of ingredients for vaccines, enable a strategic shift away from fossil fuels and to support the production and distribution of electric cars. Delving deeper into the products within the supply chains, semi-conductors include the components to solar panels, which originate largely in China. This potentially creates an over-reliance on one single source of a key sustainability component.

So the role of China in these supply chains is of equal importance across the world. China is the largest exporter globally of semi-conductors and electric car batteries. The value of its exports of semi-conductors is roughly five times higher than those of the US for example. However, the US exports more semi-conductors to China than it imports (in 2020 US$1.33bn was exported to China versus US$1.06bn). In other words, there is a dependency on China’s supply of semi-conductors but the US appears less dependent than the rest of the world.

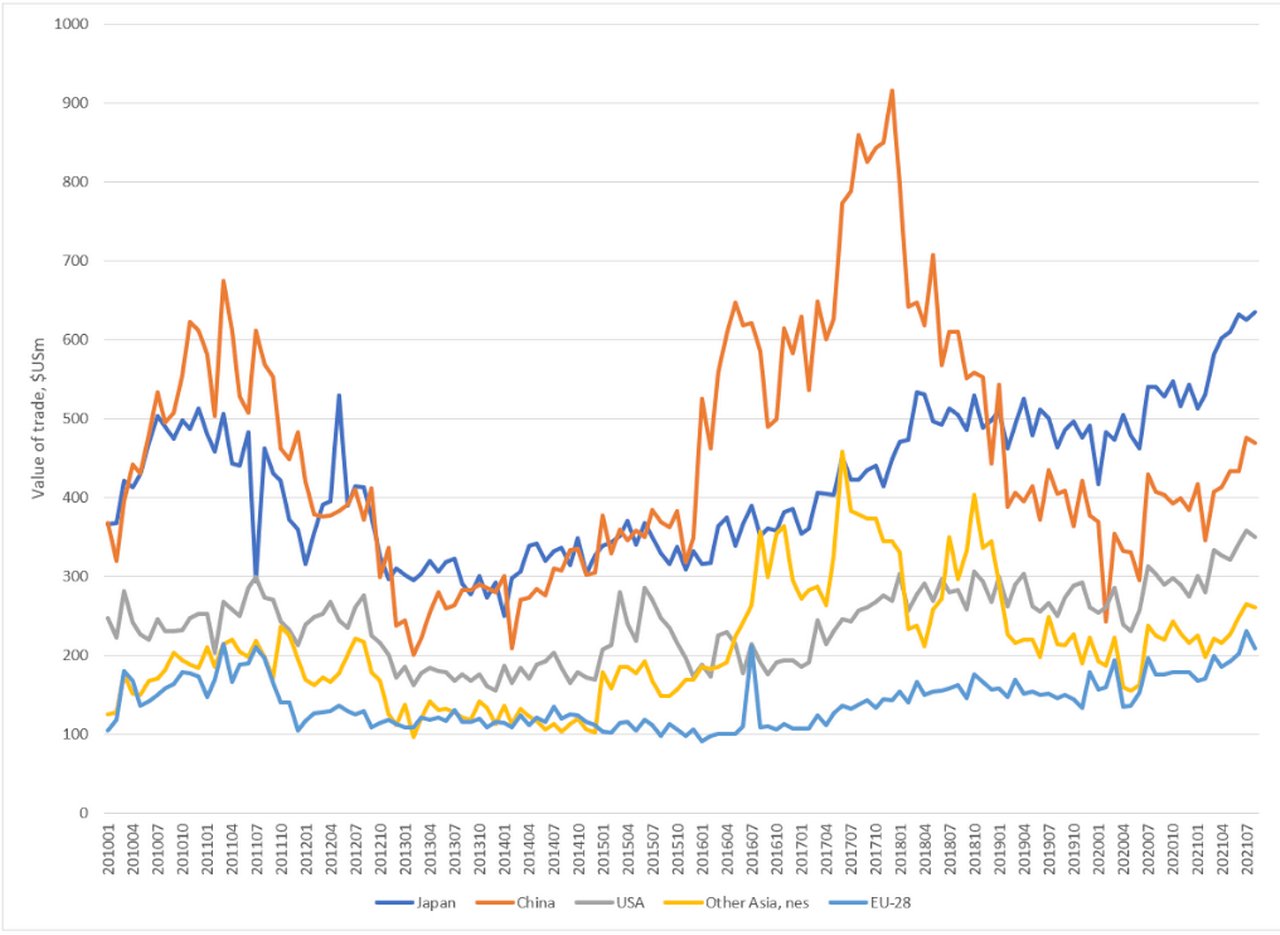

Figure 2: China's exports of critical supply chains, January 2010-August 2021, US$USbn

Source: Coriolis Technologies

NOTE: EU 28 includes the UK as this was valid until the end of 2020

Other exporters

China is not the largest supplier of critical mineral fuels for electronic supply chains but there is a lack of transparency in this particular supply chain due to the importance of a non-specific exporter, ‘Asia not indicated elsewhere’. For example, that region is the largest supplier of cobalt, and its supply dropped sharply in 2019, ahead of the Covid pandemic. However, taken as a whole, Japan has become the largest country supplier overall, by overtaking China at the start of 2019 (see Figure 3).

China’s trade in critical minerals has been falling in value terms since the end of 2017 and although more recently its exports appear to have picked up, it has not restored its position as global leader. Of more interest is that a non-specific area – which could include Taiwan, or supply chains that were diverted due to trade tensions between China and the US – is an important exporter in this sector.

Figure 3: Top five country exporters of critical mineral fuels for electronics (January 2010−August 2021) US$m

Source: Coriolis Technologies

“Trade is changing and local sourcing and reduced supply chain dependency has been a pattern that has emerged across all countries”

Seismic shifts

But beyond the strategic and geopolitical context of supply chains and their disruption, are equally significant underlying patterns that reveal shifts over time. As trade changes, local sourcing and reduced supply chain dependency has been a pattern that has emerged across all countries. This results not only from the obvious supply chain vulnerabilities exposed in the past 18 months, but also from tensions between the world’s major trading partners and blocs that go back to a more “weaponised” trade rhetoric evident since 2017.

More importantly, we are seeing big shifts in patterns of consumer demand and lifestyle choices that filter into the way in which trade is organised and conducted as we move away from the accepted norms of globalisation that apparently underpinned a more multilateral trade agenda. The US focus on resilience in critical supply chains as much reflects the desire to make sure that domestic consumers have access to products that have supported work, leisure and health through the pandemic.

Take computer games, for example. Chinese exports have fallen by 33% since October 2017. They rely heavily on semi-conductor imports and, in July 2018, the US imposed its 25% tariffs on Chinese semi-conductor exports. Between December 2017 and December 2018, Chinese imports of semi-conductors halved as the country ramped up self-sufficiency in production to become less reliant on semi-conductors supplies from elsewhere. Little wonder that toy exports have slowed.

Computer games themselves became a symbol of the pandemic. As the world locked down, individuals resorted to online for work and leisure purposes. Demand for semi-conductors soared, exacerbating pre-existing shortages, as did demand for delivery meals, online shopping, online meetings and even online exercise classes.

All of this is well-documented but represents another fundamental shift in the global labour market that has accelerated recently: alternative ways of working enabled by technology, automation and the Internet of Things (IoT). This shift has long been recognised and formed the basis of Germany’s Industrie 4.04 industrial strategy and, perhaps ironically, China’s Made In China 20255 strategy as well. Both approaches recognise the threats to mid-tier jobs, the balance between leisure and work time, the increasing importance of distributed supply chains and self-sufficiency and cyber security threats as we move to a more connected existence.

Evolving trade patterns

Lorry driver shortfall across Europe is 400,000 according to Transport Intelligence6

What we are seeing now is the impact on the labour market unfolding. There are new types of skills shortages – where we once talked about shortages of engineers and scientists, we now discuss global labour shortages in sectors such as hospitality, healthcare, distribution and construction. Where we once talked about education and training for life-long learning, the focus is now on re-training to take jobs as lorry drivers. Where we used to promote the free movement of people across borders globally, our attention has moved to “levelling up” within countries.

The past 18 months has, arguably made us lose confidence in the global trading system’s ability to carry on supporting economic development and growth through thick and thin. At the end of 2020 world trade was still around 11% lower in value terms compared to 2019, and the climb back to pre-pandemic levels will be sluggish while the virus remains in circulation.

But because trade has changed, we shouldn’t necessarily interpret these numbers as negative. The Covid-induced slowdown has thrown into sharp relief the patterns of shifting work and shifting consumption that were self-evident long before the pandemic: we are buying more online, we are having more ‘stuff’ delivered to our doors, we are more reliant on electronic devices for our entertainment and we are demanding more in terms of ‘sustainable’ goods from alternative energy to electric cars to locally sourced food products. Industrie 4.0, the fourth Industrial Age is here and this is beginning to appear in the statistics.

Can trade be more sustainable?

So can trade be sustainable over the year ahead? The short answer is yes, because it has to be. At present, exported products that negatively impact the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals outnumber products that impact the UN SDGs positively in a ratio of four to one. This isn’t surprising since fossil fuels, automotives, machinery and electronics are the top four traded sectors in the world. While the EU has put together a taxonomy to allow banks and regulators to identify sustainable business activities in supply chains,7 there are only 230 of them that are seen to ‘Do No Significant Harm’ and that potentially contribute positively to climate change mitigation.

Yet there is around US$17trn a year in trade finance globally that could be made sustainable if the value of trade picks up to pre-pandemic levels of around US$21trn.8 According to McKinsey, the value of supply chain finance within this is around US$7.3trn.9 This is a substantial proportion of trade that could be made more sustainable through closer monitoring of supply chains. While the US supply chain resilience framework and the EU’s Open Strategic Autonomy10 document’s focus might be geopolitical in origin, they also reflect important shifts in policy towards greater regulation of environmental, social and governance (ESG) criteria across supply chains.

Banks will have to respond to these requirements to track sustainability in their clients’ supply chains, and corporate sustainability financial disclosures are becoming mandatory. If demand is shifting, so too will the patterns of goods and services that are supplied. Trade is transforming and it is the responsibility of everyone in the trade space to make it sustainable in every sense of the word.

Sources

1 See https://wapo.st/3AXPeke at washingtonpost.com

2 See https://bit.ly/3zQ6g2k at whitehouse.gov

3 See https://bit.ly/39SxMle at stlouisfed.org

4 See https://bit.ly/3zQwemp at plattform-i40.de

5 See https://bit.ly/2Y3cgY8 at nhglobalpartners.com

6 See https://bit.ly/39OnZN7 at ti-insight.com

7 See https://bit.ly/3kSqyns at ec.europa.eu

8 This value is based on accepted estimates of trade finance as a proportion of total trade values of around 75%

9 See https://mck.co/3zT54uZ at mckinsey.com (chapter 3)

10 See https://bit.ly/3mbS5zV at ec.europa.eu

Go to Corporate Bank EXPLORE MORE

Find out more about products and services

Go to Corporate Bank Go to Corporate BankStay up-to-date with

Sign-up flow newsbites

Choose your preferred banking topics and we will send you updated emails based on your selection

Sign-up Sign-upSubscribe Subscribe to our magazine

flow magazine is published annually and can be read online and delivered to your door in print

You might be interested in

Trade finance and lending {icon-book}

Trade’s choking hazards Trade’s choking hazards

What happens if cargo ships can’t get through ports? Does trade grind to a halt and impact economic growth in surrounding countries? Independent trade economist Rebecca Harding examines supply chain resilience

Macro and markets, Trade finance and lending {icon-book}

More Beyond the greenwash

More could be done to address the social reasons why unsustainable trading activities continue, argues Rebecca Harding. Having systems in place to check mirror trade data and supporting communities with alternative sources of income are good starting points

More MoreTRADE FINANCE, SUSTAINABLE FINANCE

Sustainability and supply chains Sustainability and supply chains

While ESG principles and alignment start at home, they must carry through to supply chains, explain Deutsche Bank’s Anil Walia and Bjoern Goedecke in BCR’s World Supply Chain Finance Report 2021