25 June 2021

Despite their volatility, cryptocurrencies are gaining acceptability as an alternative asset class. However, mass adoption is unlikely, and in the meantime, central bank digital currencies are gaining traction, reports flow’s Graham Buck

MINUTES min read

While the world grappled with Covid-19 in 2020, central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) quietly moved forward, largely unremarked upon. By contrast, private cryptocurrencies such as bitcoin continued to attract publicity.

The Bahamas, which in 2018 announced a project to develop its own CBDC with the declared aim of promoting financial inclusion and access across the islands, was first off the starting block. The nation of around 390,000 people officially launched the so-called ‘Sand Dollar’ through the Central Bank of The Bahamas in October 2020,1 although reports suggest a low-key launch, with around US$130,000-worth of Sand Dollars in circulation over the early weeks, against US$508m in traditional Bahamas dollars. As Deutsche Bank research analyst Marion Laboure notes, “with The Bahamas having 90% penetration for mobile devices and one of the highest per-capita incomes in the Americas, the adoption rate of the Sand Dollar is likely to be high and quick. Furthermore, the Sand Dollar is pegged to the US dollar (USD); in effect, it can be seen as a pilot release of a digital USD by proxy.”

A CBDC initiative is also well advanced in the Eastern Caribbean, under the supervision of the Eastern Caribbean Central Bank. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has encouraged the development of a common digital currency across the region to lessen dependence on cash and cheques. The test phase of a digital Eastern Caribbean dollar has been run over a private permissioned blockchain on IBM’s Hyperledger Fabric.

But both are relatively small-scale CBDC initiatives and could be regarded as the hors d’oeuvre before the main course, which will be served when the world’s main central banks are ready to launch their own CBDCs.

The People’s Bank of China (PBoC) is well ahead of Western institutions, following a transition in the Chinese authorities’ attitude towards digital currencies. The PBoC began reviewing the concept in 2014. By 2020 it was ready to commence trials of a PBoC-backed ‘digital yuan’ as part of the government’s push for a cashless society, with a full-scale release expected ahead of the Beijing Winter Olympics, which opens on 4 February 2022. As Laboure notes, the Chinese adoption rate of the government’s CBDC – influenced by existing consumer habits and demographics – is likely to be faster than in most other countries.

Along with China, another front-runner is Brazil,2 where Roberto Campos Neto, President of the Banco Central do Brasil (BCB), has said that a BCB-backed digital real may be ready for entry into mass circulation as early as 2022.3 “To have a digital currency, you need an instant payment system that is efficient and interoperable; an open system, where you can create competition; and a currency that has credibility, is convertible and international,” he added. As part of its digital agenda, in February 2020 the BCB launched its official payment network, Pix, for instant money transfers and QR code scanning. Mass adoption of Pix is scheduled during 2021 and last October, Brazil’s Economy Minister, Paulo Guedes, announced that the initial public offering of the digital bank Caixa Econômica Federal was provisionally pencilled in for April 2021 (although this has now been put back to “early 2022”4).

Fed and ECB more circumspect

“It’s more important for the US to get it right than to be the first”

By contrast, in the US the Federal Reserve (Fed) declares itself to be unperturbed by such progress elsewhere in the world and under no pressure to respond with a Fed-backed CBDC. Fed Chairman Jerome Powell maintains that a launch should go ahead only once concerns over potential vulnerability to cyberattacks and counterfeiting are addressed. “This is one of those issues where it’s more important for the US to get it right than to be the first,” he told the IMF in October 2020. More recently, Powell has spoken of it taking “years rather than months” until the Fed is ready, adding that, in the meantime, it is investing heavily in the supporting technology and addressing the questions posed by CBDCs.

The European Central Bank (ECB) has also been studying the concept of a CBDC, which it believes could mitigate the risks to financial stability and monetary sovereignty posed by private cryptocurrencies.5 It published a draft report in October 2020 and is expected to clarify its attitude towards a digital euro by summer 2021. In January 2021, ECB President Christine Lagarde spoke of a digital euro being launched within five years,6 although she noted that it will “take a good chunk of time to make sure it’s safe”. Participating in an online conference organised by Reuters, she also called for global regulation of bitcoin, adding: “For those who assumed it might turn into a currency – terribly sorry, but this is a highly speculative asset which has conducted some funny business and some interesting and totally reprehensible money-laundering activity.”

There have also been calls for the Bank of England (BoE) to be at the forefront of developing a digital pound. Like the ECB, the Bank has been reviewing the possibility of a digital version of its currency for several years, and in April 2021 announced the joint creation, with HM Treasury, of a Central Bank Digital Currency Taskforce to coordinate the exploration of a potential UK CBDC.7 BoE Governor Andrew Bailey has also dismissed the idea that private cryptocurrencies will gain widespread acceptance. Speaking at the World Economic Forum in January 2021,8 Bailey commented that, while digital innovation in payments would continue, bitcoin and other private cryptocurrencies lacked the essential features to make them more than transitory.

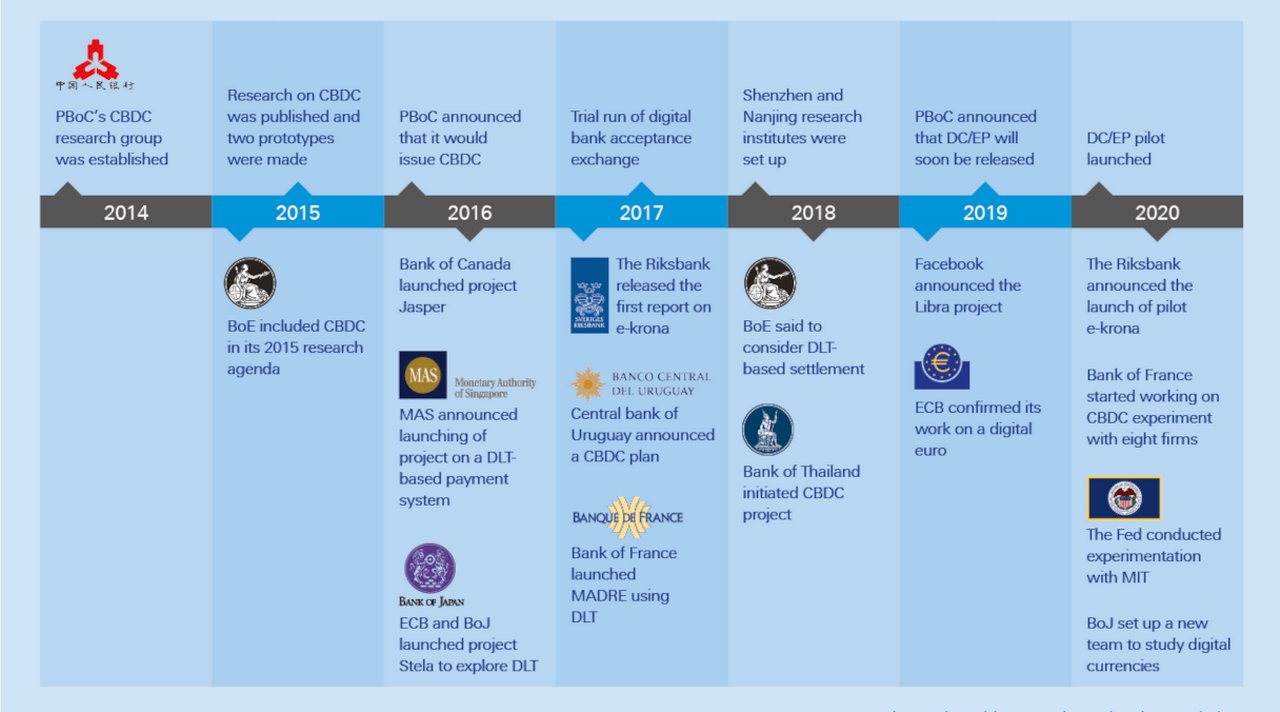

Figure 1: Timeline of CBDC research and experiments in various countries

Sources: Deutsche Bank, Goldman Sachs and various websites

The fact that the world’s central banks have warmed to the idea of backing a digital currency marks something of a sea change over the past decade. Writing in February 2020,9 Euromoney Editorial Director Peter Lee commented: “First central banks ignored cryptocurrencies, then they mocked them, next they fought them and now they are building their own. Before long, CBDCs will be in use, with possibly startling consequences.”

The shift in attitude has been tracked by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), which has monitored speeches given in recent years by central bank governors and other senior figures. As flow reported in December 2020,10 the BIS found that as the number of speeches on the topic of digital currencies steadily increased, the tone had shifted from negative to rather more positive.

The BIS has noted that many forms of CBDC are possible “with different implications for payment systems, monetary policy transmission as well as the structure and stability of the financial system”. The two main variants are wholesale CBDCs and general purpose, also known as retail CBDCs. “The wholesale variant would limit access to a predefined group of users, while the general purpose one would be widely accessible.”

Disintermediation

“The world has shifted from asking whether digital currencies will succeed, to how and when they will become mainstream”

“The world has shifted from asking whether digital currencies will succeed, to how and when they will become mainstream,” notes Laboure in her February 2021 white paper, The Future of Payments Series 2 – Part II. “In the long run, CBDCs will displace private cryptocurrencies and become the norm,” she predicted.

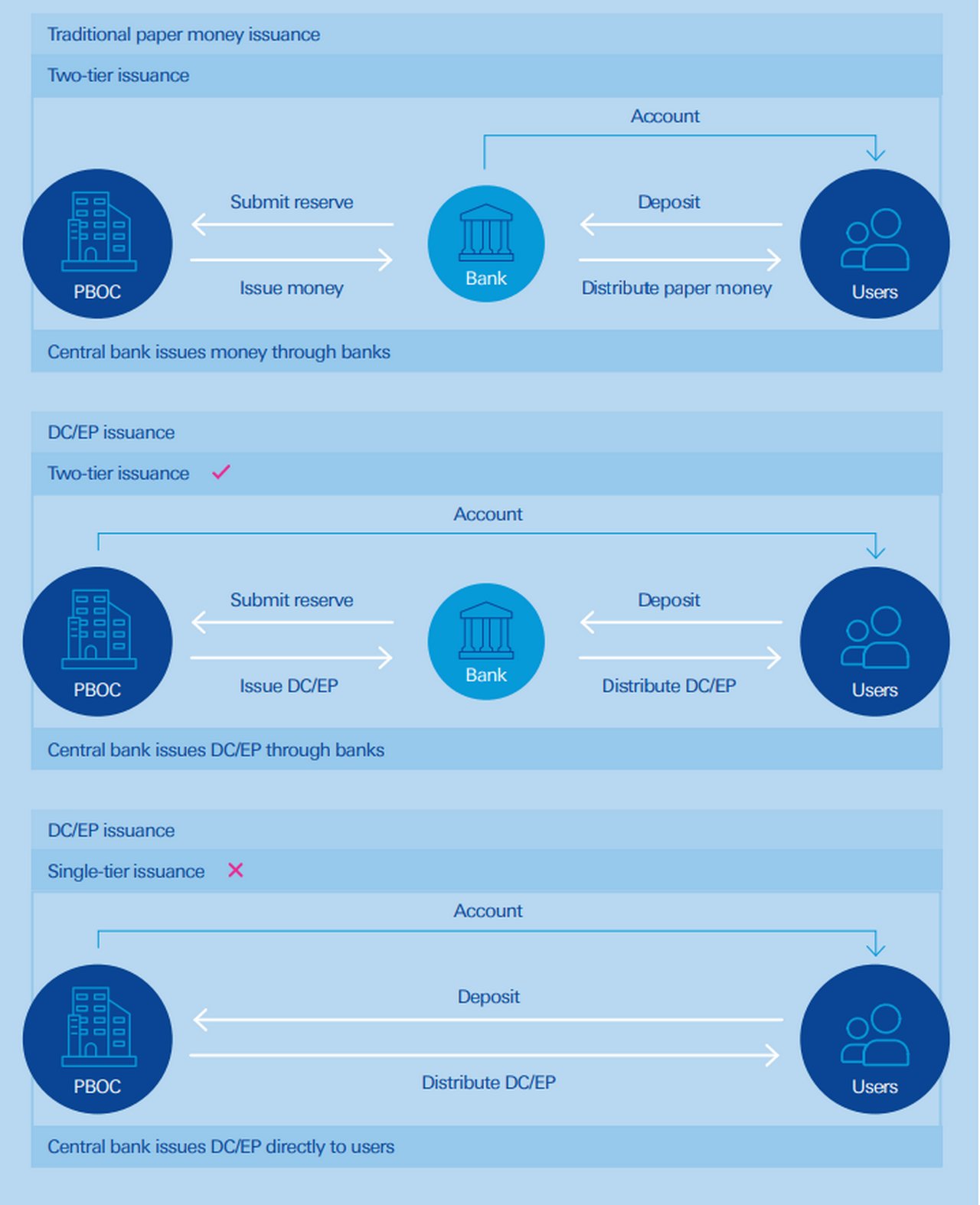

Laboure warns that “with bank accounts paying low interest rates, a CBDC has a high potential to disintermediate the banking system. People might choose to hold their money directly at the central bank. Obviously, this would disrupt legacy bank franchises and impact financial stability [see Figure 2].

Figure 2: Key design features of central bank money

Source: Deutsche Bank

Some degree of disintermediation is an inevitable consequence of a successful CBDC. Thus, commercial banks need to consider how to react to a prospective loss of deposit funding.” But she adds that “currently, the digital currency model favoured by most central banks seems to be two-tier issuance. As with a traditional currency, transactions would be decentralised and supply would be centralised.”

The demise of cash

If more by circumstance than design, Covid-19 has set the stage for the widespread adoption of CBDCs. In her paper, Laboure writes of the pandemic accelerating the demise of cash by four or five years – even if it is not about to disappear anytime soon.

However, she makes the point that Asia and China are leading the way and notes how, at the end of 2018, “around 73% of internet users in China used online payment services” (up from 18% in 2008) and that the World Bank says that “85% of Chinese adults who bought something online also paid for it online… This is significantly higher than other emerging economies.”

Laboure also believes that emerging market economies are likely to continue to lead the race in developing digital currencies. The Future of Payments Series 2 – Part II considers the barriers that advanced economies must first overcome for their populations to adopt them. The principal two obstacles are low interest rates and cultural/privacy norms. Cash is still widely regarded as a “store of value” and a “safe haven”, and it appears that higher interest rates for digital currencies will be needed before this perception changes.

Yet even in the first weeks of the Covid-19 crisis, Western consumers were showing greater readiness to transition to a cashless society. Concerns that traces of the virus can linger on notes and coins lent impetus to the move away from cash to contactless payments for regular daily purchases, which was further encouraged by an increase across many countries in the maximum limits applicable to ‘tap and go’ contactless cards. For example, the UK upper limit rose from £30 to £45 in April 2020, with the March 2021 Budget confirming reports of a further rise to £100.

In Sweden, the country that over recent years has gone furthest along the path towards a cashless society, the Riksbank is reviewing the possibility of making payments using the e-krona “as easy as sending a text”.11 In December 2020, Sweden’s Minister for Financial Markets and Consumer Affairs, Per Bolund, announced the Riksbank had launched a study (which will run to November 2022) into the logistics of switching the country to the digital currency. This prospect has alarmed Sweden’s banks, which are concerned that customers could also transfer their money from deposit accounts and into e-krona.

Bitcoin’s limitations

Although CBDCs are set to make a much greater impact over the coming years than private currencies, it is the latter – in particular bitcoin – that continue to regularly attract media attention.

This is due, at least in part, to bitcoin’s chequered history since its launch in 2009 and its regular bouts of price volatility, as record highs are reached and are often followed by sharp falls. Nonetheless, after recent developments, even a conservative daily such as the Financial Times (FT) asked ‘Is bitcoin going mainstream?’ in February 2021. The FT noted that investor interest in bitcoin, which up to then had come mainly from family offices and hedge funds, was widening out.12

While more consumers are taking an interest, a reality check is needed. As Alexander Bechtel, Head of DLT and Digital Asset Strategy at Deutsche Bank Corporate Bank, notes, bitcoin is not money and thus presents no competition to fiat currencies. And the differences between the two greatly outnumber the similarities – a private cryptocurrency and a CBDC are two very different things that address different use cases. “One is a decentralised, permissionless, censorship-resistant, borderless open system to store and transfer value,” notes Bechtel. “The other is digital cash, issued by a central bank, where it is unclear if it will be token- or account-based, or based on a blockchain or a centralised database.

“So the efforts around developing a CBDC are not driven by any fear that bitcoin could crowd out fiat money such as the euro, but rather by the prospect of a diminishing role for cash and increasing competition from stablecoins. Only its hardcore fans believe that bitcoin will serve as a means of payment in the future.”

Moreover, the discussion about retail CBDCs is a non-technical one, focusing mainly on whether non-banks should be given access to digital cash. “Only at a second or third step might we possibly be talking about blockchain,” notes Bechtel. “None of the advanced projects are using blockchain; indeed, in the euro area it looks as if we could get an account-based version of a CBDC that has nothing to do with blockchain. China apparently uses some cryptographic tools, but this is still far away from bitcoin or other cryptocurrencies.”

Gaining traction

Yet, although it continues to attract plenty of adverse publicity, bitcoin has proved resilient, with major payment services providers having lent it further credence as an alternative asset class.

In October 2020, PayPal announced that customers could begin buying and selling bitcoin and other virtual currencies. More recently, BNY Mellon said that it will begin holding and transferring cryptocurrencies for its asset management clients, and Mastercard declared: “We are preparing right now for the future of crypto and payments… This year Mastercard will start supporting select cryptocurrencies directly on our network.” The global payments group subsequently added, in February 2021: “Mastercard is actively engaging with several major central banks around the world as they review plans to launch new digital currencies, dubbed CBDCs, to offer their citizens a new way to pay. Last year, we created a test platform for these banks to use these currencies in a simulated environment.”13

Bitcoin’s pioneering of blockchain, or distributed ledger technology (DLT), for the currency’s creation, distribution, trading and storage has also encouraged members of the US tech quintet of Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Netflix and Google (aka FAANG) to work on developing their own cryptocurrencies. As Katharina Paust-Bokrezion, Head of Payments Policy in Deutsche Bank’s Political Affairs team, observes, there are a number of incentives. “The use cases for the industry and society are diverse and there are key benefits for money on a DLT compared to today’s payment landscape,” she says. “Payments today are largely digital, not just since the introduction of cryptocurrencies by FAANG. But the benefits of cryptocurrencies mainly derive from the programmability of the money itself and their usage in a cross-border context. A future-proof regulatory framework is a key basis to institutionalise DLT-based payment use cases.”

To date, the most high-profile FAANG initiative has been Facebook’s June 2019 announcement of plans to launch its global digital currency by mid-2020. Originally named Libra, the initiative quickly encountered strong opposition from G7 leaders, alarmed by the absence of supervision and regulation in the proposal.14 The launch date was delayed (to “early 2021” according to reports, but this was still unconfirmed at the end of Q1) and scaled back in scope to a digital coin (now rechristened Diem) backed by the dollar, with other currencies to be added at a later date.

Amazon, having launched its first UK contactless grocery store in London in March 2021, is also working on a digital currency.15 The group’s Digital and Emerging Payments division has revealed it is developing a system for enabling customers in emerging markets to “convert their cash into digital currency”.

So what will the future bring? “Capital markets are very excited about tokenised assets and CBDCs beyond just cryptocurrencies,” says Samar Sen, Global Head of Digital Products at Deutsche Bank Securities Services. “But these types of digital assets are still nascent and the ecosystem requires more maturity.”

Over the next five years, Sen expects some cryptocurrencies to become standard allocations in investor portfolios, while many others are as likely to fail. CBDCs “will start to gain traction, along with some approved stablecoins for use in settlements, payments and remittances,” he predicts.

And will bitcoin endure? While it could still establish a long-term role for itself, some of the more ambitious claims for its future seem exaggerated, to say the least.

Sources

1 See https://reut.rs/3r3ikc2 at reuters.com

2 See https://bit.ly/3qZViD5 at atlanticcouncil.org

3 See https://bit.ly/38TGaR8 at ledgerinsights.com

4 See https://bit.ly/33Cv2W3 at labnews.com

5 See https://bit.ly/3qZVwKr at ecb.europa.eu

6 See https://bit.ly/38UhqIK at forbes.com

7 See https://bit.ly/33EHzbA at bankofengland.co.uk

8 See https://bit.ly/3txh9TV at ledgerinsights.com

9 See https://bit.ly/2OKy9r2 at euromoney.com

10 See Digital currencies, differing motives at flow.db.com

11 See https://reut.rs/3s0srQg at reuters.com

12 See https://on.ft.com/2P0hHTj at ft.com

13 See https://mstr.cd/3vCfPRu at mastercard.com

14 See https://bit.ly/3cDvYxe at forbes.com

15 See https://bit.ly/3ePBzDy at techradar.com

Go to Corporate Bank EXPLORE MORE

Find out more about products and services

Go to Corporate Bank Go to Corporate BankStay up-to-date with

Sign-up flow newsbites

Choose your preferred banking topics and we will send you updated emails based on your selection

Sign-up Sign-upSubscribe Subscribe to our magazine

flow magazine is published annually and can be read online and delivered to your door in print

You might be interested in

CASH MANAGEMENT, MACRO AND MARKETS

When will digital currencies become mainstream? When will digital currencies become mainstream?

The Bahamas launched the sand dollar, a nationwide central bank digital currency (CBDC) last October. flow’s Graham Buck reports on why its move will be followed by others around the world over the coming months as CBDCs take on cryptocurrencies

MACRO AND MARKETS, TECHNOLOGY

China focuses on post-Covid goals China focuses on post-Covid goals

Having warded off the pandemic’s full impact, the world’s second-largest economy can focus on achieving technological self-sufficiency and developing its central bank digital currency, reports flow’s Graham Buck

TECHNOLOGY, MACRO AND MARKETS {icon-book}

AI in motion: Tracking the smart money’s journey AI in motion: Tracking the smart money’s journey

Deutsche Bank Senior Strategist Marion Laboure takes a closer look at the explosion in artificial intelligence (AI) commercial applications by examining patent growth areas