10 August 2022

Periods of disruptive innovation have always transformed the inequality map. Digital technology has transformed and democratised finance, for example. In her new book, Deutsche Bank Research Senior Strategist Marion Laboure explains how fintech is tackling financial exclusion, and what more can be done

Published in 2022 by Harvard University Press, the book 'Democratizing Finance: The Radical Promise of Fintech' was completed during the Covid-19 pandemic, when my co-author Nicolas Deffrennes and I were confined to our respective homes and teaching online, instead of at Harvard's campus in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

The experience concentrated our minds on the profound changes to the ways people were handling payments. Physical cash was regarded a potential transmitter of the virus, and with the willingness to comply with social distancing, digital payments were rapidly becoming mainstream. We saw how the pandemic accelerated efforts by governments to deploy central bank digital currencies (CBDCs), and we reflected on the resilience of consumer trust in online payment security. Just as the 2008 global financial crisis catalysed change – allowing for innovative companies to emerge and thrive – the pandemic appears to have acted as another catalyst – or perhaps a ‘fertiliser’ – for these new payment technologies to become mainstream.

Financial inclusion

We also reflected on how the uneven distribution of resources such as labour, capital and technology can limit economic growth. But beyond its macroeconomic benefits, financial inclusion leads to significant social and personal benefits. Consider the basic benefits of having a bank account: it allows individuals to save, earn interest, balance household consumption and raise productive investment. Moreover, a bank account can empower women and give them more economic equality.

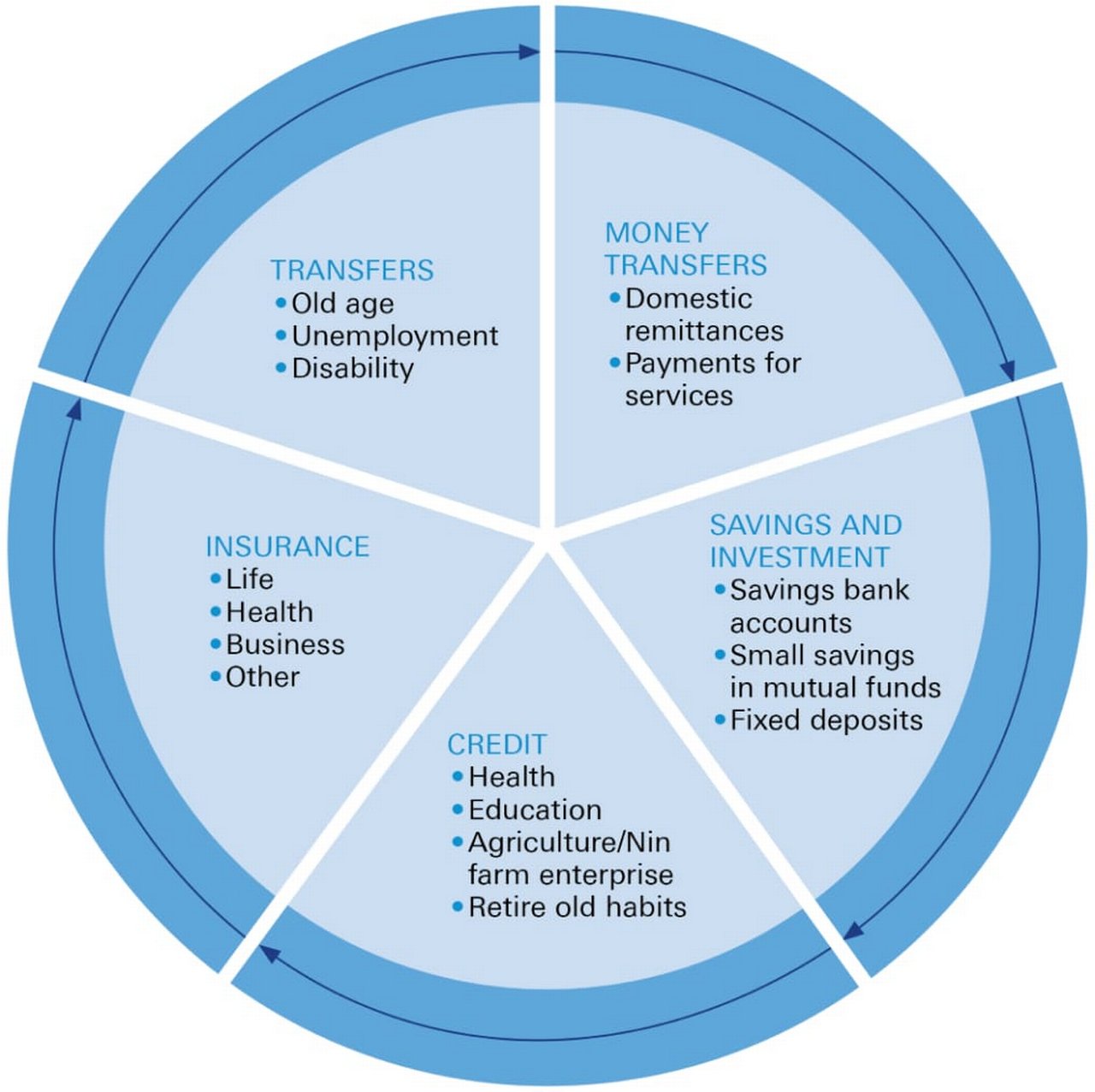

Figure 1: Essential lifecycle of financial needs of a low-income people

Source: Democratizing Finance: The Radical Promise of Fintech

Although more people have gained access to bank accounts, there is still considerable work to be done. By 2017, 1.7 billion adults were still unbanked, according to the World Bank Global Findex. If we look deeper into that database, we find that nearly half the world’s unbanked people lived in seven countries: Bangladesh, China, India, Indonesia, Mexico, Nigeria and Pakistan. But people need more than a bank account, and the financial needs of individuals and families evolve along a lifecycle, as summarised in Figure 1.

When households have access to financial products such as money transfers, savings and investment, credit, insurance and pensions, they tend to enter an upward cycle towards increased wealth and wellbeing. By contrast, the absence of these basic financial services can derail low-income households and push them into debilitating debt cycles and spiralling poverty traps.

Furthermore, in developing countries, a large share of GDP comes from small and medium enterprises (SMEs), including subsistence farmers, traders and shopkeepers. Although formal financing exists in all countries, many traditional banks refuse to lend to SMEs because the amount borrowed is typically too low to cover transactional costs related to the bankers’ time and evaluation services. Many owners of land, homes, farms or shops have no official proof of ownership, rendering their properties ineligible as collateral. Weak regulations and laws are an added complication. With seasonal agricultural loans, agents do provide credit to farmers, but only if the agent can sell the crops or take a percentage of profits.

How fintech can help

A large proportion of people in developing countries work in traditional sectors such as agriculture. Because innovation and productivity growth tend to take place within the nonfarming sectors of the economy, rural citizens are often excluded from the formal economy. This presents a strong need for technology that can enable higher productivity by improving the speed, reliability, transparency and cost of information delivery.

Mobile phone ownership is widespread among the unbanked. Globally, in 2017 about 1.1 billion unbanked adults – representing about two-thirds of the 1.7 billion unbanked adults in the world – had a mobile phone. The rising rate of global cell phone use has the potential to advance financial inclusion. Technology has ensured that even basic devices can enable transactions, thus reducing the need for branch banking. In sub-Saharan Africa, relatively simple text-based mobile phones have powered the spread of mobile phone accounts via services such as M-Pesa in Kenya.

Further details of emerging market penetration levels are set out in the book, and the success of fintech in emerging markets is not just because of its ability to tap into a large, tech-literate population, but also by reaching those who had previously been financially excluded. South Africa, Mexico and Singapore are on track to become significant fintech players, with borrowing and financial planning as the fastest growing fintech services. All of this indicates growing opportunities for the expansion of mobile banking.

However, for financial services to move out of the bank branch, providers require:

- Physical infrastructure, such as electricity, mobile and internet networks

- Technology solutions, such as mobile phone applications and sufficient security

- Financial institutions, such as banks and insurance companies, that are willing to customise products and services for the underserved

- Government regulation in the telecoms, banking and insurance sectors

Fintech and government

While fintech can provide significant assistance to low-income populations in emerging economies, it requires the commitment of social actors with power and influence to direct technological designs towards the goal of improving financial inclusion in emerging economies. The Chinese and Indian governments, for example, have made financial inclusion and equality central aspects of their economic policies.

Fintech can facilitate direct links between governments and individuals. Government to Person (G2P) applications include wage and pension payments, health subsidies, unemployment allowances and disability benefits. Digitising these types of social transfers can help enrol large numbers of underserved persons in social programmes while reducing costs – which could incentivise governments to promote G2P applications. Digitising government payments could increase bank account ownership among the adults worldwide without a bank account – around 80 million of them opened their first account to collect public sector wages. Governments can enable even greater financial inclusion by digitally transferring funds, subsidies and pensions.

However, for digital government transfers to work, the technology ecosystem must be ready to use. All citizens should be able to open and access their accounts without difficulty – and without intermediaries exploiting the financial illiteracy of underserved people.

Recommendations for developing countries

First, developing countries should launch programmes to digitise IDs and create a positive ecosystem for e-commerce and financial services. The Indian government has led the way with its Aadhaar ID system, which has helped more people get bank accounts and access other financial services.

Second, the public sector should develop partnerships with start-ups to invest in telecom and payment infrastructure for rural areas. In emerging economies, the combination of mobile, e-commerce and digital payment options helps growth, better development and higher living standards. Governments should continue working with the private sector to develop public-private partnerships offering access to broadband, e-commerce and payment solutions in the most remote areas.

Finally, newly created fintech ecosystems are a great stepping stone for government services and wealth redistribution. One of the biggest barriers to creating social security or other redistribution services is the lack of official identities among the most remote citizens. Without IDs and residential addresses, citizens cannot access government services, and they become vulnerable to theft, loss and corruption. Fintech solutions can help to gather valuable data and create digital wallets or other means for people to receive benefits.

Marion Laboure is a Senior Strategist at Deutsche Bank Research and a Lecturer at Harvard University. 'Democratizing Finance' was co-written with Nicolas Deffrennes and published by Harvard University Press.

“Fintech is profoundly changing our economy and our lives. This important book is necessary reading for anyone who cares about the future of our economy or our society”

Lawrence H. Summers, Former United States Secretary of the Treasury, Charles W. Eliot Professor and President Emeritus, Harvard University

“Laboure and Defrennes highlight the growing importance of financial inclusion and technology. With a wealth of data and case studies, this book demystifies fintech and explains its role democratising finance”

Christian Sewing, CEO of Deutsche Bank

You might be interested in

Community

Charging back to work Charging back to work

How could people from low-income backgrounds get higher-paying jobs after the pandemic hit? flow reports on how Deutsche Bank Americas Foundation’s New Initiatives Fund supported the work of ETF@JFFLabs, a US employment technology fund that is helping make this happen

MACRO AND MARKETS, CASH MANAGEMENT

Is the crypto party over? Is the crypto party over?

The presumption that Bitcoin and its peers offer a hedge against inflation has been debunked by recent sharp falls. The plunge extended to stablecoins, which are supposedly far less volatile. flow summarises Deutsche Bank Research analysis on crypto perception and reality

Trade finance, Technology {icon-book}

Data as a building block for digital trade finance Data as a building block for digital trade finance

How can the trade finance industry create a digital ecosystem? Pamela Mar, Managing Director, Digital Standards Initiative, International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) explores how bridging trade and financial flows could be the key