24 August 2021

As the Philippines heads towards its national elections in May 2022 and grapples with Covid-19, flow highlights the country’s resilience and potential for those investing in and trading with ASEAN’s second largest market

MINUTES min read

On 6 August, the Philippines put its Manila capital region into a two-week lockdown as its health ministry reported 10,623 new coronavirus cases, which Reuters reported as “the largest single-day jump in infections for almost four months”.1

But thanks to its strong demographics and public finances, as well as highly robust infrastructure and financial ecosystems, this is a country well-placed to weather not only the interruption from further Covid-19 disruption but also to continue its economic growth trajectory – irrespective of the outcome of the May 2022 elections. This article draws on Deutsche Bank perspectives in both Manila and Singapore on why the future looks bright for the Philippines.

Rich human capital

“The Philippines is very much about importing and exporting skills and services at all qualifications levels”

If the success of a business rests upon its people, that truism applies to countries too. Deutsche Bank’s Burkhard Ziegenhorn, Head of Global Transaction Banking and Corporate Bank Coverage for ASEAN says that, “in addition to its agricultural, maritime, and mineral wealth, the Philippines’ key resource is its skilled labour force”. He adds, “The Philippines is very much about importing and exporting skills and services at all qualification levels, whether it is for medical practitioners, seafarers and domestic professionals or providers of banking or high-value shared service centres (SSCs).”

This labour force is a powerful economic resource and growth driver, lying behind various trends, such as the on-shore growth of business process outsourcing (BPO), and the offshore growth in the number and importance of Filipino seafarers, who are now the linchpins of the global merchant shipping sector and thus of world trade. BPO, for example, has seen global corporations – such as Japan Tobacco, Johnson & Johnson and Conti Tech − entrust key functions to SSCs in Manila and its environs on the island of Luzon. The Philippines’ most significant earnings are thus generated by its human capital: intangible exports by overseas businesses operating BPO service functions onshore; and remittances by its nationals operating in service sectors offshore, who comprise 10% of the country’s population and who contribute 10% to GDP.

Regarding the longer-term prospects of the country’s labour force and population generally, Michael Chua, Chief Country Officer for the Philippines at Deutsche Bank reflects that “the Philippines has a young, growing population where GDP per capita has also been steadily increasing”. Demographic fundamentals such as a large proportion of the population aged 25 years or younger led Chua to confirm that “the prospects for economic growth, for increased spending, and for a more technologically savvy population are clearly there”.

Many other countries have large, youthful populations, but Chua thinks the Philippines gains a long-term competitive edge from its “blended cultural influence...and very strong ties to the US and Europe while remaining Asian at heart”. Such “cultural and economic ties” are visible in the diaspora’s footprint, which through a virtuous circle “helps cement those cultural and historical roots”. With arguably one of the strongest western influences, derived from the Spanish and American colonial rule, it has become one of the go-to places for BPO, a sector currently employing 1.3 million people and which, in 2020 contributed US$26bn to GDP. With a young, skilled and English-speaking population that is very comfortable with technology, this trend can be expected to continue, furthered by the Government’s provision of incentives to BPO companies.

Deutsche Bank itself has made the most of the labour supply advantages here and has an SSC in Manila −‘Deutsche Knowledge Services’. This employs a large number of staff and undertakes global functions including business performance management, product control, financial reporting and consolidation, and human resources.

Growth prospects and Covid-19 responses

Juliana Lee, Deutsche Bank’s Singapore-based Chief Economist points out that the Philippines reported a surge in GDP growth, to 11.8% year-on year (yoy) in Q2, marking its strongest gain in over three decades, from -3.9% in Q1, supported by low base effects. On a seasonally adjusted quarter-on-quarter basis (QoQ sa), however, the economy contracted 1.3% in Q2, vs. 0.7% in Q1, due to the Covid-19 resurgence. She added that “while its Q3 growth outlook has been clouded by recurring Covid outbreaks and re-imposition of lockdown in the Manila capital region for two weeks, data do not point to a plunge in mobility,” suggesting relatively limited impact. See Figure 1 for changes in mobility and new Covid cases.

Figure 1: The Philippines: Rising infection vs mobility

Source: Google, Deutsche Bank Research

Solid public finances and economic programmes

Turning to GDP per capita in the Philippines, as Chua points out, this has roughly tripled since 2000, or put another way, the nation had produced 81 consecutive quarters of economic growth.2 Despite the recent troughs, in purchasing power parity terms growth has actually risen, given inflation has fallen steadily since 2015 (aside from a sharp rise in pork prices, which gives fans of the national dish adobo cause to complain). But no matter how rich the human capital was that produced such growth, this could not have been sustained without very solid management of the economy by successive administrations and by the Philippines’ central bank, Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP). Pre-pandemic, a solid fiscal position, GDP/debt ratio of below 40%, and an investment-grade credit rating were the fruits of this public finance management success.

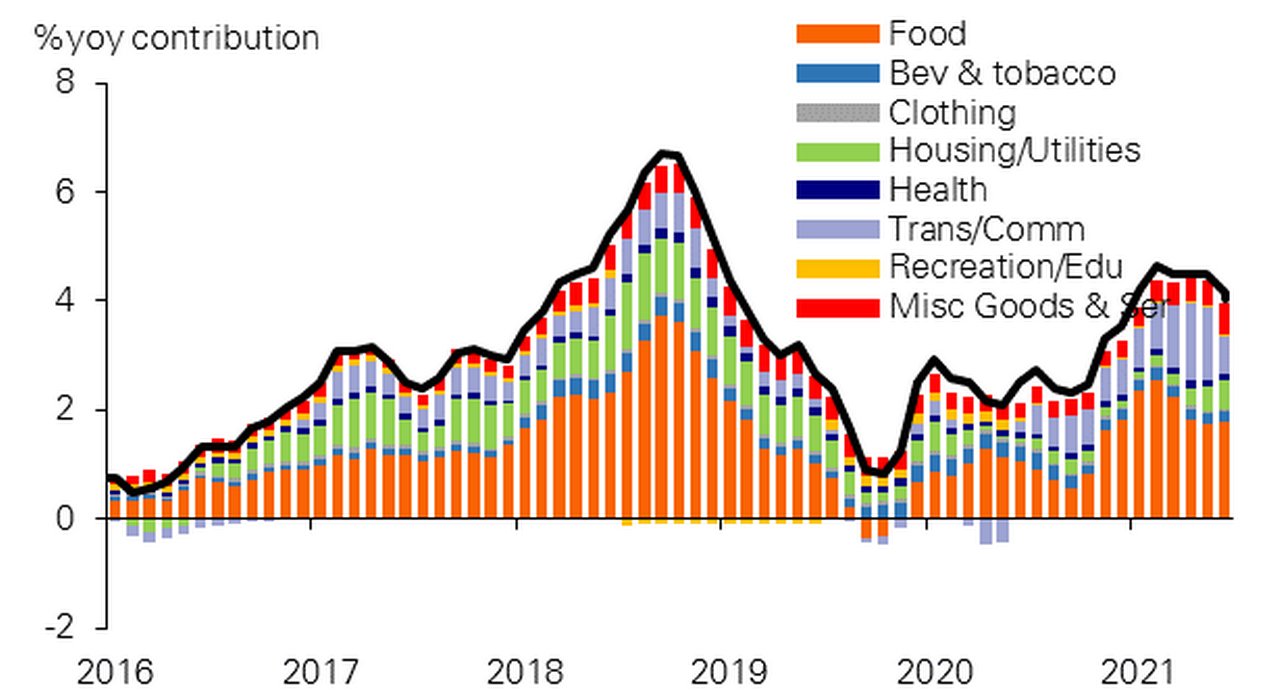

Inflation is “trending lower” according to Martin Tirol, Head of Global Transaction Banking for Deutsche Bank in the Philippines, as shown in Figure 2. Indeed, Chief Economist Lee sees the Philippines sustaining a downward trend in inflation until early Q1 2022, with the quarterly average falling to 3% from 4.4% in Q2 this year, and its rebound thereafter to remain within the limits of BSP’s inflation target. “Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas left the policy rates as we expected, marking its sixth consecutive month of steady policy decision, noting its continued support for economic recovery,” she explains. “Like Deutsche Bank, BSP also saw risks to growth in Q3, noting risks to the economic recovery and highlighting the importance of “targeted fiscal and health interventions, especially the acceleration of the government’s vaccination programme.”

Figure 2: Philippines: Drivers of CPI inflation

Source: Asia Macro Insights, 28 May 2021, Deutsche Bank Research

Tax reforms and FDI

Four tangible and game-changing improvements made by the current administration’s economic programmes cover tax reforms, infrastructure development, the ease of doing business, and foreign exchange liberalisation.

Several substantive and procedural changes have been made to boost government tax collection rates. This was needed, because as recently as a decade ago it was estimated that only one-fifth of VAT payable was actually collected. Measures which were started under previous administrations (such as the naming-and-shaming of tax evaders) have continued under the current administration, which has expanded the VAT base and lowered corporate and personal tax rates. Once among the highest corporate tax rates in ASEAN, the recent Corporate Recovery and Tax Incentives for Enterprises Act lowers taxes from 30% to 25% for large companies operating in the Philippines, and from 30% to 20% for smaller companies.3 Also, tax loopholes have been closed, especially regarding cigarettes and fuel.

Such tax reforms seek to work in tandem with efforts to boost foreign direct investment (FDI). With 13 different government agencies promoting FDI, the current administration has sought to coordinate their efforts.4 But such efforts to boost FDI and cut red tape are also necessarily intertwined with the Philippines’ efforts to improve its infrastructure and the ease of doing business. Such efforts are simultaneously both modest and grand in scope, and both highly local and global in nature. Cutting taxes and red tape and signing international trade accords to attract FDI will not have the desired effect if roads stay gridlocked or impassable, or if infrastructure improvements remain focused on the already highly developed island of Luzon, which hosts Manilla and half of the country’s population.

Infrastructure development

President Duterte’s flagship initiative is his ‘Build, Build, Build’ programme5, which has seen infrastructure spending rise to an average of 5% of GDP, more than double the investments of the past four administrations. Around 100 projects are included in the programme, one-third of which feature public-private co-investment, the terms of which the government has been careful to ensure are attractive for foreign investors. Regarding equity, the infrastructure improvements seek to improve linkages between the 7,000 plus islands comprising the Philippines, to help economic growth occur more evenly.

On 23 July the Philippines news agency announced the country is “inching closer to reaping the gains of economic development through the ‘Build, Build, Build’ programme of the Duterte administration, which resulted in the construction of several infrastructure projects nationwide”. It reported that the Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH) has completed a total of 29,264km of roads, including those that have been widened and rehabilitated. In addition the DPWH said that 5,950 bridges were completed, including those that have been widened (1,366), retrofitted (1,805), rehabilitated (1,389) and replaced (297), while some 738 local bridges have been constructed”6

Mactan-Cebu International Airport, the second busiest international airport in the Philippines. It is located in Lapu-Lapu City on Mactan Island, a part of Metro Cebu.

Several other major projects have already either completed, such as the recently opened Bohol-Panglao International Airport, or are well underway, such as the passenger ferry port on Mindanao and the nearly completed New Clark City, a mixed residential and office development, which should accommodate 1.3 million people. But some projects are also local and relatively modest in scope: streamlining of licensing and planning laws is intended to allow, for example, more telecommunications masts to be built, to allow the Philippines to be further inter-connected for development and to take advantage of trends arising as part of the fourth industrial revolution.

Ease of doing business

In addition to streamlining the paperwork required to do business, successive governments have boosted transparency and digitalisation. For example, the late Benigno Aquino III, President from 2010-16, pushed for government accounts and decisions to become available online, a trend which has continued. But aside from the domestic, a further strand of the government’s efforts to boost the ease of doing business is highly international in nature: it has recently reaffirmed its interest in joining the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), the proposed pan-regional trading agreement.7 Joining any such TPP that comes into being would require some prerequisite domestic reforms, which the current administration is working hard to achieve.

Foreign exchange liberalisation by BSP

Foreign exchange liberalisation is vital in giving overseas investors confidence that they will be able to take out any money put in and made in the Philippines. In addition, an economy that receives 10% of its GDP via remittances absolutely needs an efficient FX and payments infrastructure. Accordingly, over nearly two decades the BSP, in conjunction with successive governments, has effected changes to liberalise the FX market, such as an expanding list of underlying transactions to allow FX purchase, reducing or removing capital controls and easing documentary requirements. This policy strategy is widely expected to continue. As recently as 11 August, the BSP announced further rule changes designed to ease payments to e-commerce businesses and settlement of trade transactions with non-residents, among others.8

Potential hiccoughs?

Such favourable long-term growth factors can of course be undermined by security flare-ups, further resurgences of the pandemic, or other setbacks. However, even here there is also cause for optimism.

First, the Duterte administration remains focused on the growth and development of his home region of Mindanao, the country’s second most populous island and which for decades has faced unrest due to insurgents.

Second, as an archipelago with more than 7,000 islands, any nationwide vaccination rollout will always be a challenge. But this also serves as a natural break against the spread of the virus as it creates self-contained bubbles, thereby granting the Philippines’ public health system more space to be battle-ready to deal with the current − and any future − pandemic. Strict enforcement of lockdown measures and an increasingly digital financial sector have also contributed towards the country’s economic resilience.

Financial ecosystem

Martin Tirol identifies three factors that have helped further boost this resilience of the Philippine banking sector (despite Covid):

- Adequate capitalisation of banks;

- Low exposure to bad debts; and

- The ability to support the economy during the pandemic through the availability of credit and other services.

Such financial resilience is in part also a by-product of the calibrated liberalisation policy of the BSP, the main regulator of the banking sector. The BSP has maintained this investor-friendly approach for more than 25 years.

For more than half a century the Philippines only had four foreign bank branches operating with a commercial banking license. Today, more than half of the 45 universal and commercial banks in the country are foreign-owned, a fact which Chua ascribes to the “huge overseas interest in the Philippines in general and in the banking sector in particular”. Deutsche Bank itself has maintained a presence in the Philippines for nearly half a century, starting as an offshore banking unit in 1975 before upgrading its franchise to a commercial banking license in 1995. The bank finally attained full universal bank status in 2011.

The period of expanding foreign investment and robust growth started well, with the Philippines under Fidel Ramos (President from 1992 to 1998) weathering the Asian financial crises better than others. Early on, the government realised the importance of not overly depending on any one source of capital. Meg Angeles-Dayrit, Head of Coverage & Origination at Deutsche Bank in the Philippines, notes that it is not just state actors such as the government and BSP which learnt from the crises: the Philippines’ home-grown business conglomerates also used the experience to learn and build greater resilience by being “very disciplined in their foreign currency borrowing and very prudent in ensuring they have multiple funding mechanisms”. With domestic Philippine banks adopting a wait-and-see approach to lending in the early stages of the pandemic, businesses that had foreign banking relations were able to continue to invest and to seize M&A opportunities through record levels of capital market issuance.

Along this path towards resilience and access to capital, Deutsche Bank has been successfully partnering with its clients, who range from state-owned enterprises and financial market participants like asset managers and insurers through to domestic and foreign businesses. The Bank supported the Republic of the Philippines in completing its recent US$3bn sovereign bond issuance, the Republic’s largest in over 10 years and surpassing the prior issuance of US$2.75bn executed in December 2020.9

Deutsche Bank’s Tirol notes that the bank’s services also range from trade and supply chain finance, and foreign exchange to credit and rates trading, and from vanilla structured finance to complex capital markets transactions. Such services have garnered customer recognition and industry awards, such as The Asset ranking Deutsche Bank ‘Best Domestic Custodian’ in the Philippines from 2012 to 2021 and ‘Best Sub-Custodian’ in 2018 and 2020, and Euromoney ranking it ‘Best Trade Finance Provider’ in the Philippines in 2019.

The Bank is also well poised to help its clients move into the next frontier of banking: digitisation. Chua notes that the share of digital payments by volume only grew from 1% of total in 2013 to 8-11% by 2018. Yet in the 12-month period from March 2020 to March 2021, transactions via local payments systems InstaPay and PesoNet already surged nearly four-fold. Cash and cheques are still favoured by consumers, but Tirol considers the pandemic accelerated “a conscious shift to digital payments”, adding that “one can expect digital payments to increase in volume and value in the coming years”. This ties in with the BSP’s ‘Digital Payments Transformation Roadmap 2020-2023’, which aims to see 50% of retail sales move from being paper-based to digital, and aims to see financial inclusion increase to 70% of adults.10

“The banking system remains healthy despite the pandemic, and key corporates also have strong balance sheets”

Solid platform for growth

Tirol reiterates that “our key export is people and skills”, and adds that the BPO sector’s headcount is set to grow 5% in both 2021 and 2022. Chua thinks the “long-term outlook for the Philippines is promising”, noting that the “banking system remains healthy despite the pandemic, and key corporates also have strong balance sheets”. And regardless of the results of next year’s elections, the Philippines will be able to rely on its favorable demographics and solid fundamentals to generate further growth.

In Filipino folklore, there is a story called “Pliant like the Bamboo”, by local author Ismael V. Mallari. It describes the bamboo as bending with the wind but not breaking, remaining standing and rooted to the ground after the wind has passed. Such are the attributes of the Philippines and its people – qualities like resilience, patience, humility and the ability to withstand difficult challenges such as Covid-19 and economic stress, before emerging stronger and more resilient and still standing proud.

Thick stems of bamboo in the countryside of Luzon island, Philippines

Sources

1 See https://reut.rs/3D9am8C at reuters.com

2 See https://bit.ly/3zdjPcu at adb.org

3 See https://go.ey.com/3B5CcRq at ey.com

4 See https://cnb.cx/3mrIUgb at cnbc.com

5 See https://bit.ly/3sFSj4T at gov.ph

6 See https://bit.ly/388GJG1 at gov.ph

7 See https://s.nikkei.com/3mr9WVk at nikkei.com

8 See https://bit.ly/3kjgxyk at gov.ph

9 See https://bit.ly/3kkJppK at gov.ph

10 See https://bit.ly/3B4egO3 at gov.ph

Go to Corporate Bank EXPLORE MORE

Find out more about products and services

Go to Corporate Bank Go to Corporate BankStay up-to-date with

Sign-up flow newsbites

Choose your preferred banking topics and we will send you updated emails based on your selection

Sign-up Sign-upYou might be interested in

Dossier ASEAN

Doing business with ASEAN Doing business with ASEAN

The ten countries that comprise the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) make up a cohesive, cooperative trading bloc first established in Bangkok, Thailand on 8 August 1967. This microsite provides a guide in the form of a series of in-depth flow articles and multimedia interviews on the opportunities for doing business within and from the region

Dossier ASEAN

Indonesia’s place in the sun? Indonesia’s place in the sun?

Indonesia’s Omnibus Law seeks to boost foreign investment, jobs, and trade. flow examines its background and the opportunities this could bring as the country recovers from Covid-19 economic shock