04 June 2021

Indonesia’s Omnibus Law seeks to boost foreign investment, jobs, and trade. flow examines its background and the opportunities this could bring as the country recovers from Covid-19 economic shock

MINUTES min read

President Charles de Gaulle of France once despaired that it was difficult to govern a country that had 246 different types of cheese. Indonesia’s President Joko Widodo – more familiarly known as Jokowi – may on occasion feel taxed by governing a country which has 1,300 different ethnic groups among its 270 million citizens, themselves scattered across 13,600 islands.

Navigating such complexities has long thwarted efforts to reform. However, Widodo is attempting a multi-pronged injection of change through new legislation. Despite its bland name, ‘Law Number 11 of 2020 on Job Creation’ − thankfully shortened to the ‘Omnibus Law’ − is anything but. This law aims at economic and job growth, by reducing red tape and easing the entry of foreign capital and expertise into Indonesia.

"[The Omnibus Law] it will add value to the government’s efforts in handling the pandemic and support economic recoveries"

“Significant support from the business community in [the law’s] implementation is essential, as it will add value to the government’s efforts in handling the pandemic and support economic recovery in a balanced and synergetic manner,” said Widodo in his remarks promoting the Omnibus Law to global leaders at the World Economic Forum in November 2020.1

This article examines the scale of the challenge faced, the potential upside, and how the Omnibus Law will operate to achieve its intended outcomes with insights from the Jakarta-based team at Deutsche Bank, which is Indonesia’s longest standing foreign bank.

Challenges

The governance challenge is indeed considerable. Indonesia is the world’s largest island country and with upwards of 270 million people its population is exceeded only by China, India and the US. Sitting atop vast reserves of hydrocarbons and mineral deposits, Indonesia also suffers from the so-called resource curse, or paradox of plenty.

Its location in some of the world’s busiest sea lanes with abundant fish stocks makes the country prone to overfishing by crews drawn from its many neighbouring states. Widodo claims that upwards of 90% of trawlers in Indonesian waters are illegal and their presence constitutes violations of sovereignty.2

Indonesia is an ecotourist’s dream, but its terrain can be unforgiving: it has the most active volcanoes and suffered the most fatalities from the 2004 Boxing Day tsunami off Northern Sumatra that killed nearly 230,000 people. Holding the world’s third largest stock of pristine rainforest, Indonesia has also overtaken Brazil in its rate of illegal deforestation, which silts up its rivers - affecting the fishermen, tourism and shipping businesses, and communities that depend on them. Jakarta – many of whose residents rely on ride-hailing apps and Twitter3 −has an average income equivalent to that of Poland’s citizens. By contrast, on some outlying islands like Maluku, where much of the population struggles to access electricity and basic sanitation, the average income is equivalent to that in the Congo, or one-tenth that of Jakarta.

Indonesia’s governance challenge is both a by-product of its varied geography, and its history. Aspects of the country still lie in the shadows cast by Presidents Sukarno and Suharto, the two military-backed strongmen who successively controlled Indonesia for more than 50 years (and its struggle for independence following three centuries of Dutch rule) until 1998 (and its struggle for solvency following the 1997 Asian financial crisis). For example, several political parties, the police, and other key state institutions still feature important personnel (and their relatives) and political styles that were fostered under the Sukarno and Suharto regimes.

But Suharto’s ousting in 1998 also marked a watershed moment in bringing to fruition Indonesia’s founding principles of state philosophy, also known as pancasila - including greater stability, freedom of the press and religion, and its now-entrenched democracy. The following year also marked the start of pemekaran − or the transfer of power − from Jakarta to villages and districts (bypassing provinces), which has transformed Indonesia into one of the most decentralised countries in the world. As a way of keeping the various ethnic, religious, and secessionist influences from boiling over while citizens were accorded their democratic voice, decentralisation has worked. Unfortunately, greater autonomy and more layers of governance mean decentralisation has also made reformasi more challenging for Jakarta. However, reform is indeed required to boost growth.

Potential

Figure 1: Indonesia’s steady GDP

Source: Deutsche Bank Research

Deutsche Bank Research anticipates Indonesia’s growth to rebound to 4.5% this year from a contraction of 2.1% in 2020, then accelerate further to 5% in 2022 led by surging exports (see Figure 1). Indonesia’s GDP, the Asia team point out, “has been remarkably stable – hovering around 5% before the pandemic”.

“Thereafter, its growth is likely to accelerate further to 5%, on the back of a stronger rebound in domestic demand. This assumes a meaningful progress in vaccination; the share of Indonesia’s population who received at least one dose of Covid vaccine stands at 6%. The peak of its Covid-19 infections appears to have passed in Q1, amid mobility restrictions, which have eased in Q2, allowing for a rebound in growth in Q2.” they explain in their 28 May Asia Macro Insight report (see Figure 2).

However, the World Bank estimates that growth could have been higher.4 The country’s full potential was fettered by legacy structural challenges, like market-distorting fuel subsidies, cumbersome import/export processes at ports, and underinvestment in infrastructure, healthcare, and education. Even legacy systems in land records have hampered domestic and foreign investors: one study found differing maps used by various layers of government meant that concessions allocated to investors comprised 130% of all land in one province, storing up potential disputes that could derail developments.5

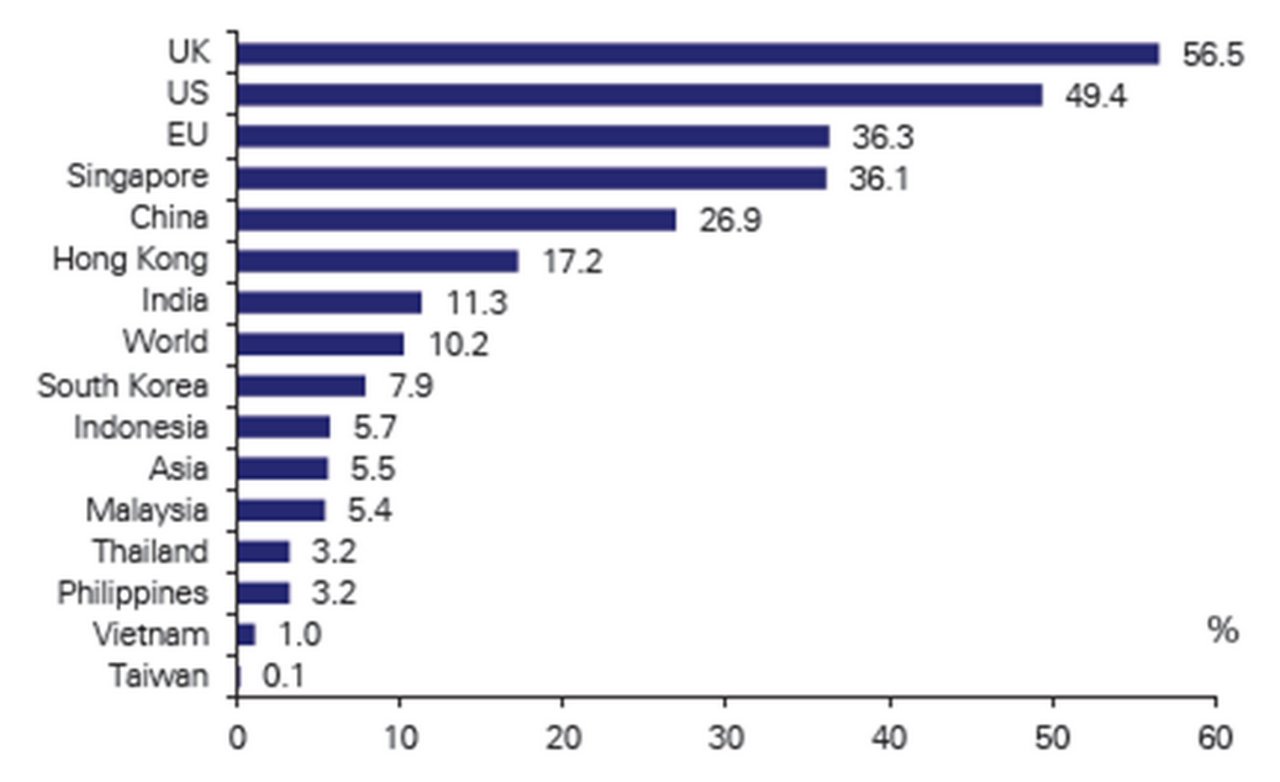

Figure 2: Asia vaccination rate remains low (% of people who received at least 1 dose)

Source: CEIC, Deutsche Bank Research

Note: China vaccination rate estimated by assuming people get their second dose one month after their first one

Already the 16th largest economy in the world, The World Bank expects Indonesia to be the seventh largest by 2030.6 “Indonesia is a country with significant potential”, says Burkhard Ziegenhorn, Head of Global Transaction Banking and Corporate Bank Coverage for ASEAN at Deutsche Bank. He notes that many of the building blocks for growth are already in place, including demography, capital markets, and banking infrastructure.

"Indonesia has an expanding consumer market, which provides an enormous opportunity"

“As the world’s fourth most populous nation Indonesia has an expanding consumer market, which provides an enormous opportunity”, adds Ziegenhorn. The last 15 years have seen Indonesia’s middle class rise from 7% to 20% − or 52 million − of its population,7 a trend to be bolstered by increased domestic consumption. Half of Indonesia’s population is under 28 year old, and the World Bank estimates that 28 million people will enter its workforce between 2015 and 2030.8

It is not just Indonesia’s democratic institutions that have developed a reputation for stability: so too have its governments for their fiscal management, and its central bank regarding monetary policy. Such prudence helped Indonesia - and the rupiah - largely weather and recover from the capital outflows triggered by the ‘taper tantrum’ of 2013, when the country was one of the so-called ‘fragile five’ group of emerging markets impacted by the surge in US Treasury yields. Today, “government incentives on dividends have triggered vibrant capital markets activity” says Samir Dhamankar, Head of Global Transaction Banking and Securities Services for Indonesia at Deutsche Bank, “which is often a sign that interest in the market is coming back and that cross-border inflows will follow in due course”. Having established itself in Indonesia in 1969, Deutsche Bank is now also the country’s largest custodian of foreign assets, working with the Ministry of Finance, state-owned enterprises (SOEs), domestic retail clients, and also Japanese and Korean clients.

As the world’s most populous Muslim democracy, Indonesia is also the world’s largest issuer of sharia’h-compliant sukuk sovereign bonds. The trend that may well continue given rising religiosity is being acknowledged by the government through its efforts to expand Islamic banking and certification of halal consumer products.

With an already highly developed financial infrastructure and inter-bank payments ecosystem, and with increased internet penetration and adoption of smartphones by its youthful population, Indonesia is poised to ride the next wave of banking, financial, and fintech innovation. “Although people and small businesses have preferred the comfort of cash payments during the pandemic, digitalisation is inevitable, and banks will see a lot more growth in digital payments”, says Vonty Hermawati, Head of Corporate Cash Management for Indonesia at Deutsche Bank. “E-commerce offers opportunities, including for capital markets”, adds Hermawati, noting that Indonesia’s largest e-commerce platform Tokopedia has been considering an IPO.9 Covid-19 is accelerating some of these trends, spurring a flurry of recent telecoms merger and fintech funding rounds,10 such as that for e-wallet company LinkAja.11

A decades-long underinvestment in infrastructure has also been reversed. As a noted aficionado of heavy metal music, President Widodo also likes another kind of heavy metal - and has encouraged building projects that include metro systems, power plants, ports, nearly 1,000 km of new roads, and rail links such as the China-funded high-speed line between Jakarta and Bandung. Initiatives like encouraging e-procurement, using funds saved by cutting fuel subsidies, and deploying SOEs for such projects have helped the President and his core team of highly able technocrat ministers to get these projects financed and started earlier. Enabling higher employment and income levels at home, whether from more value-added manufacturing or increased tourism in Batavia and beyond, could also assist Indonesia’s ambitions abroad. As befits its size and importance within ASEAN, Indonesia is already the association’s de facto leader, taking bold positions recently on issues such as climate change and unrest in Myanmar. A stronger economic underpinning at home could enable Indonesia to assume the greater regional and global leadership role in foreign policy that it desires.

Bali, Sunrise over Jatiluwih Rice Terraces

Omnibus Law

Logging in the upper reaches of Indonesian rivers inadvertently impinges upon the efforts of other industries and communities further downstream. Similarly, a more joined-up strategy produced through greater alignment between the policies of the different but interdependent ministries could be more efficient and boost several areas domestically, providing Indonesia with a stronger economic foundation. And this is exactly what the Omnibus Law seeks to achieve.

"Previously, 350 sectors were closed to foreign investment: now only 46 strategic sectors remain blocked"

A doorstopper at 1,187 pages long, the Omnibus Law amends nearly 80 existing laws.12 Key planks of the reform concern the liberalisation of foreign investment, the simplification of licensing, the reduction of relevant tax rates, and the reformation of labour law. “Previously, 350 sectors were closed to foreign investment: now only 46 strategic sectors remain blocked − largely in areas of defence and national security,” notes Siantoro Goeyardi, Chief Country Officer for Indonesia at Deutsche Bank. Once the new investment is in, both foreign investors and domestic businesses will find a simplified licensing regime: the myriad strictures and approvals previously required are giving way to a streamlined risk-based approach. Also to be cut are the turnaround times for paperwork at ports. Once operating and making money in Indonesia, businesses will also find lower corporation tax, reduced from 22% to 20% for private companies, and from 19% to 17% for Indonesia-listed companies. While also tackling some of the aforementioned land procurement problems by amending spatial zoning laws, a key domestic plank of the reform focuses on human capital, which businesses will now find easier to redeploy.

Misunderstood by protesters as ushering in weaker workers’ rights, this item of the Omnibus Law seeks the opposite outcome. While rigid labour laws and lavish mandatory benefits were pro-employee, employers often could not afford to employ workers formally. Instead, by allowing companies to restructure and also dismiss ineffective workers, the new law − aside from creating new jobs through foreign investment - should actually shift workers from the informal sector to formal employment. This change will mean employment rights become available to more, while boosting government tax receipts. The inclusion of those previously unbanked and social welfare provisions like healthcare, pensions, and unemployment benefits. “This bolstering of the banking, healthcare, tax, and welfare regimes should further lay the foundations for Indonesia’s long-term economic growth”, adds Goeyardi.

Next steps for those investing and operating in Indonesia

Having secured a second and final presidential term in 2019, Widodo has three years left of his mandate with nothing to lose in terms of reelection and everything to gain in terms of legacy. A chunk of his second term has been waylaid by the pandemic, although Indonesia has suffered fewer Covid-19 fatalities than many countries with smaller populations.

Against this Indonesia is also among several ASEAN countries making slow progress on rolling out vaccinations, potentially delaying its recovery (see Figure 2).

The President has nonetheless been able to launch one of the most complex, contentious, and ambitious legislative efforts in Indonesia’s history in the midst of a global pandemic and debt-based market jitters regarding emerging markets generally. Widodo and his predecessors have been accused by opposition politicians of neglecting deep-rooted structural issues like the efficacy of the civil service and the role of the army. These critics also accuse Indonesia’s leaders of being Java-centric and of failing to maximise the opportunities to boost growth when conditions were more favourable during the long-lasting commodities boom. However, his impressive feat with the Omnibus Law evidences that even if the President did not make hay while the sun was shining, he at least did not let a crisis go to waste.

Deutsche Bank Research report referenced

Asia Macro Insight: Difficult policy choices (28 May 2021) by Michael Spencer, Juliana Lee, and Edwin Kwok

Sources

1 See https://bit.ly/3yVBsxH at weforum.org

2 See Wall Street Journal, ‘President Jokowi Orders ‘Shock Therapy’ For Illegal Fishing Boats, 9 December 2014 https://on.wsj.com/3cc0iQo at wsj.com

3 See https://ab.co/3x54gCv at abc.net.au

4 See https://bit.ly/3phgVQ2 at worldbank.org; and World Bank Report,“Global economic risks and implications for Indonesia,” September 2019.

5 See The Guardian, ‘Greenpeace reveals Indonesia's forests at risk as multiple companies claim rights to same land’, 2 April 2016, https://bit.ly/3pcgW7A at theguardian.com

6 See World Bank Report,“Global economic risks and implications for Indonesia,” September 2019.

7 See World Bank, 2019, ‘Aspiring Indonesia: Expanding the Middle Class’, https://bit.ly/3wSWVWs at openknowledge.worldbank.org

8 See ibid., p.181.

9 See The Jakarta Post, ‘Softbank-backed Tokopedia undecided on SPAC merger, may opt for IPO’, 17 December 2020, https://bit.ly/3g1PS6R at thejakartapost.com

10 See The Jakarta Post ‘Tech, cross-border activities set to drive Asia M&A in 2021’, 4 January 2021, https://bit.ly/3fFWI38 at thejakartapost.com

11 See The Jakarta Post, ‘Grab leads $100m funding round for LinkAja, builds R&D center in Indonesia’, 11 November 2020, https://bit.ly/3pdWCTj at thejakartapost.com

12 See https://bit.ly/34Ex8F8 at https://jdih.setneg.go.id/

Go to Corporate Bank EXPLORE MORE

Find out more about products and services

Go to Corporate Bank Go to Corporate BankStay up-to-date with

Sign-up flow newsbites

Choose your preferred banking topics and we will send you updated emails based on your selection

Sign-up Sign-upYou might be interested in

Macro and markets, Trade finance and lending {icon-book}

Heirs of Lac Long Quan Heirs of Lac Long Quan

MACRO AND MARKETS {icon-book}

On the bright side On the bright side

Caught in the slipstream, or powering ahead? Dr Rebecca Harding examines ASEAN’s trade momentum in the context of wider geopolitical disruption

Dossier ASEAN

Power of 10 Power of 10

As Thailand takes its turn to chair of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) for 2019 nine years on from its previous incumbency − and more than five decades after its original founding in Bangkok − Deputy Secretary General Aladdin Rillo talks to flow about how ASEAN is making the fourth industrial revolution part of its roadmap to economic integration