25 July 2024

A different approach to funding is needed to restore biodiversity and keep it intact. Markus Müller, Chief Investment Officer ESG at Deutsche Bank Private Bank, looks at how nature is impacting investor behaviour

MINUTES min read

Climate change, pollution and biodiversity loss are the components of a triple planetary crisis. While the former two have been on policymaker, investor, and corporate agendas for decades now, biodiversity loss has only started to receive more public attention in recent years.

That is important because an interlinked perspective is needed: depletion of nature (for economic or climate change reasons) leads to biodiversity loss and, in turn, biodiversity loss amplifies this depletion. These ecological relationships are reflected in recent global approaches to the problem, for example the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework – an international agreement featuring 23 targets to be met by 2030 and four global goals to preserve biodiversity, formally adopted at the 2022 United Nations Biodiversity Conference.1

Biodiversity is deeply enmeshed not just with nature but also with our economic system. We both take resources from biodiversity and threaten it. One estimate indicates that ecosystem services (for example, provision of oxygen, pollination, and clean water) generate benefits worth US$125-140tn per year, or more than officially reported annual global GDP (gross domestic product).2

As a result, half of global GDP is moderately or highly dependent on natural resources and 40% of global trade is directly dependent on them.3 By 2100, global GDP could be 37% lower than it would be without the impacts of global warming.4

Action

Given its economic importance, and given that it is relatively easy to identify the drivers of biodiversity loss, why are we not taking more action against it? Counterintuitively, focusing on the perceived biodiversity “financing gap”, though important, may make us approach the problem in the wrong way. This financing gap (the extra funding needed to reverse biodiversity loss) has been put at close to US$1tn a year.5

We should instead think of biodiversity funding as intrinsic to our overall economic model, not just as “add on” spending to counteract the side-effects of current degradation.

“Biodiversity is deeply enmeshed not just with nature but also with our economic system”

What this means is that solutions must be drawn from various areas of society. Some of these will be financial instruments for leveraging private investment, while others will be policy-related changes as governments need to incorporate biodiversity into their policy, legal and fiscal decision-making. This will involve both new initiatives and identifying and eliminating policy and regulatory barriers to enhance efficiency, encourage innovation and promote economic growth.

There has been some encouraging progress. For example, the European Union has enacted a Nature Restoration Law which includes binding restoration targets for specific habitats and species,6 and a Soil Monitoring Law is proposed.7 Other biodiversity legislation exists around the world, from the US’s America the Beautiful initiative to China’s National Biodiversity Conservation Strategy and Action Plan.

Localisation

We must always remember, however, that economies are ultimately built by the actions of individuals at a local level. Ecosystems and their related biodiversity also need to be considered as inherently location specific. Reconciling the general and the local is particularly important for biodiversity funding. As philosopher Elinor Ostrom has demonstrated,8 nature and biodiversity degradation are a “tragedy of the commons” – individual operators overusing a shared resource due to a lack of coordination.

Existing national or regional policy initiatives, therefore, must be complemented by more localised initiatives.

The same is true for funding methods, e.g. the Global Environment Facility (GEF), a family of funds dedicated to helping developing countries finance country-driven environmental protection projects, which has an increasingly specific interest in biodiversity. In the latest round of financing, pledges to its biodiversity focus reached a total of almost US$2bn.9

Cooperation

At the same time, financial institutions can play a valuable role in generating new revenues and exploring ways to change how existing public and private financial resources are invested. Cooperation is important here. Deutsche Bank, for example, is establishing a range of partnerships across different areas of biodiversity – including ORRAA (the Ocean Risk and Resilience Action Alliance) and the #BackBlue Ocean Finance Commitment.10

Better information provision and use will be part of this, again through collaboration – for example via the Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD), with a total of 320 companies, financial institutions and market service providers having already signalled their intent to adopt its recommendations.11 The International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) has also announced a new project to consider biodiversity. As the ISSB has said, investors are increasingly asking for more information on how to incorporate biodiversity into corporate planning, for risk prevention and, ultimately, competitive advantage.12

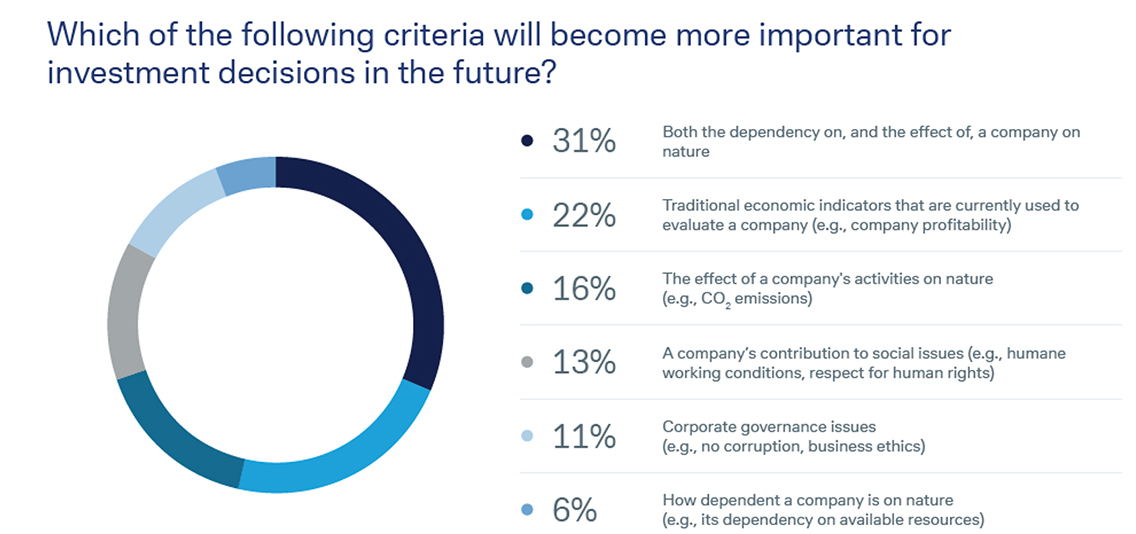

I expect more information around biodiversity at a corporate level to boost investor awareness further: almost one-third of respondents to our latest ESG survey said that we needed to consider both the dependency of a company on, and its impact on, nature (see Figure 1) – 80% of respondents also wanted stronger international regulation to protect biodiversity and the marine environment.13

Cooperation will allow us to bring action against biodiversity loss into our overall economic system, and this is how we will achieve the “sustainable transformation”.

Figure 1: Nature and investment decision-making - investor survey

Source: Deutsche Bank AG. As of November 2023

Sources

1 See unep.org

2 See sciencedirect.com

3 See weforum.org

4 See ucl.ac.uk

5 See paulsoninstitute.org

6 See environment.ec.europa.eu

7 See ec.europa.eu

8 See csgs.kcl.ac.uk

9 See thegef.org

10 See oceanriskalliance.org

11 See tnfd.global

12 See ifrs.org

13 See deutschewealth.com