25 July 2024

Carbon pricing is essential to combat climate change as it incentivises companies to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. flow’s Desirée Buchholz looks at how regulatory initiatives in the EU could impact global investment flows – and the role voluntary carbon markets play in reaching net-zero commitments

MINUTES min read

With more than 140 countries having set net-zero targets,1 including the biggest polluters – China, the US, India and the EU – hardly anybody doubts that fighting climate change is necessary. Yet, the most difficult question remains, how do we turn these commitments into action and substantially reduce global greenhouse gas emissions.

The best way to get someone to change their behaviour is by providing an incentive – and saving money has always been a strong driver for both people and businesses. In simple terms, that’s the idea behind carbon pricing: if burning fossil fuels becomes more expensive, you are incentivised to reduce emissions. Moreover, the revenue generated by carbon taxes or certificates can be used to finance the clean energy transition.

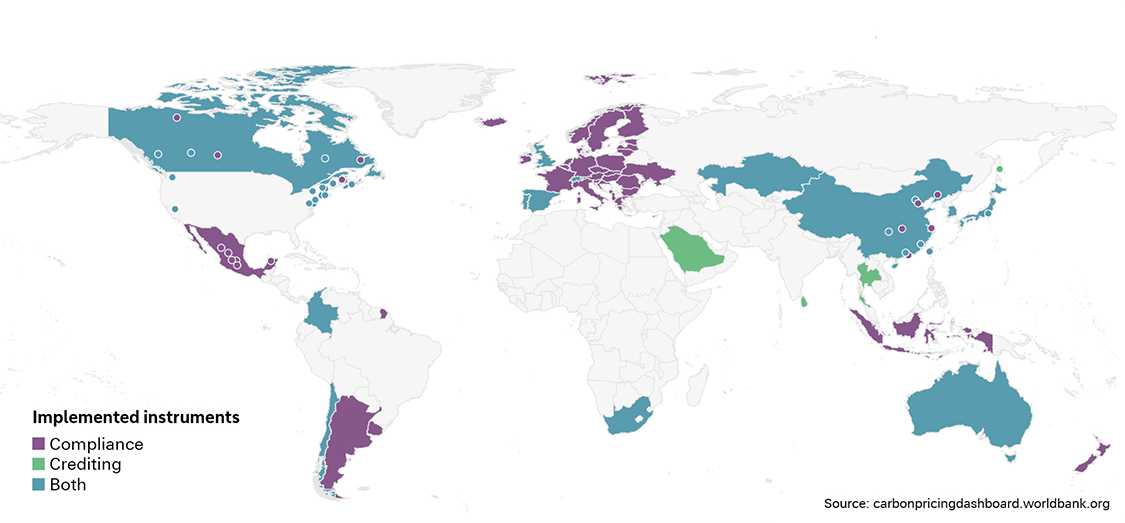

This is why more and more countries are relying on such mechanisms to reach their net-zero targets. As of May 2024, the World Bank Carbon Pricing Dashboard counted 110 carbon pricing regimes globally (see Figure 1).2 These instruments are of different quality and scope, but in general there are three distinctive approaches to carbon pricing (see Figure 2).

Figure 1: Carbon pricing instruments around the world

Source: carbonpricingdashboard.worldbank.org

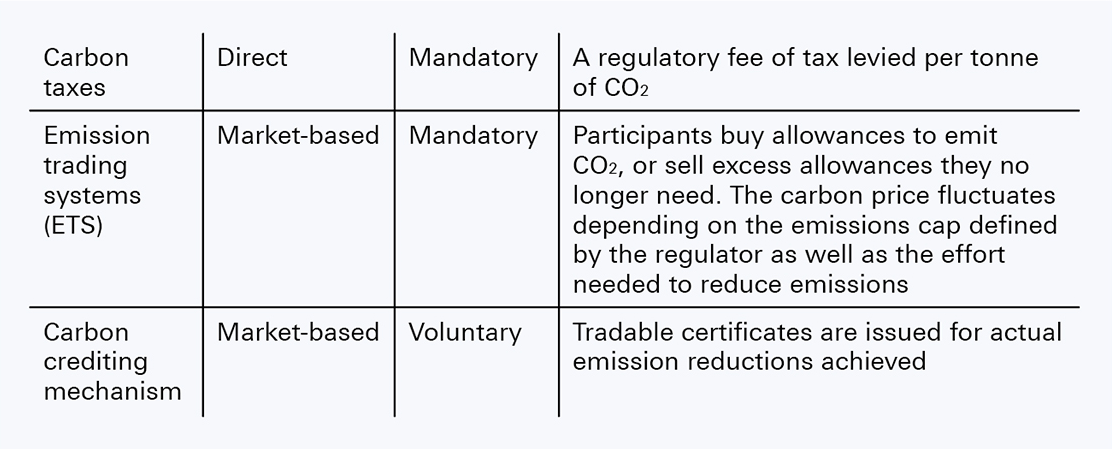

So, how do these instruments work in practice? Which industries or sectors are most impacted by carbon pricing and why is the black and white definition of voluntary versus compliance-based carbon markets no longer valid? This article addresses these questions, focusing on the revamp of the EU’s emission trading scheme (ETS) and the attempts of voluntary carbon markets to become a transparent and effective tool for fighting climate change.

Figure 2: Approaches to carbon pricing

Source: Deutsche Bank

Revamping the EU ETS

To begin, let’s look at the state of play of ETS: according to the International Carbon Action Partnership’s (ICAP) Status Report 2024, there are currently 36 such schemes in force globally, which collectively cover 18% of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. An additional 22 such schemes are under development or being considered.3

While China’s ETS, implemented in 2021, is the world’s largest in terms of covered emissions (around 5bn tons of CO₂, accounting for over 40% of the country’s CO₂ emissions)4, the EU’s ETS is the oldest and largest system in force in terms of trading volume and value.5

Yet, the EU ETS is undergoing a massive overhaul to meet the targets of the European Green Deal – under which the EU has committed to become carbon neutral by 2050 and reduce net emissions by at least 55% by 2030, compared to 1990 levels. To make this happen, the union is taking three measures:

- Creating a new emissions trading system called ETS2, which will cover CO₂ emissions from fuel combustion in buildings, road transport and small industry sectors. The system will become fully operational in 2027 and supplement the existing ETS where emitters (rather than fuel suppliers as per ETS2) are required to purchase allowances.6

- Expanding the scope of the existing ETS to maritime transport. By September 2025, shipping companies must use their first allowances for emissions reported in 2024. The share of emissions that must be covered by allowances then gradually increases until 2027.7

- Gradually phasing out free allowances for several industrial sectors.8

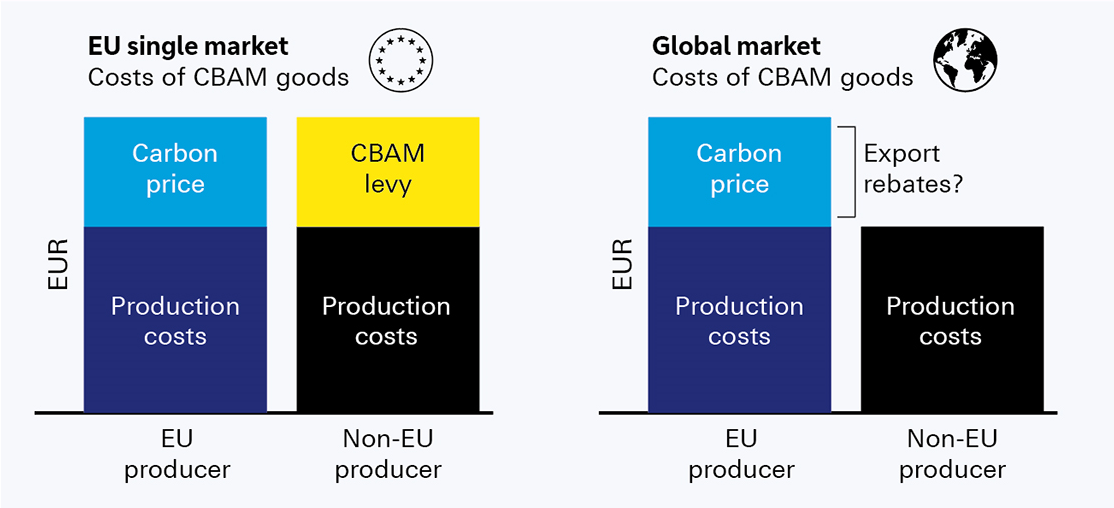

However, as the latter could incentivise firms to relocate parts of their production to countries with less stringent climate policies, the EU has also introduced a new policy tool to avoid this so-called carbon leakage: the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), which imposes a levy on imports from countries without equivalent carbon price mechanisms.

Figure 3: Schematic overview of the CBAM

Source: Institute der deutschen Wirtschaft, Deutsche Bank

Since October 2023, companies must report emissions of imported products that fall under the CBAM. These include iron and steel, aluminium, cement, some fertilisers, electricity and hydrogen and are responsible for 27% of total EU GHG emissions. The obligation to purchase CBAM certificates for the emissions embedded in those goods will start in January 2026.9

According to Marion Mühlberger and Ursula Walther, Senior Economists at Deutsche Bank Research, the new carbon border tax could lead to “trade diversion away from carbon intensive emerging market (EM) producers,” they write in their report Transitional phase of the carbon border tax has started – all you need to know, published on 30 January 2024. “Big emerging market economies most affected by the new EU import levies are Ukraine (iron & steel), India (iron & steel), Egypt (fertiliser), Russia (electricity), Venezuela (iron & steel), South Africa, Kazakhstan and Turkey.”

Moreover, they believe that CBAM will benefit countries that can use renewable energy more efficiently due to better geographic location, e.g. hydropower in Sweden. This is likely to affect “new investment decisions rather than leading to relocation of existing facilities,” they specify.

How CBAM impacts corporates

On the downside, the new reporting requirements “raise the administrative burden for importers of CBAM goods,” Mühlberger and Walther write. A September 2023 study by The Conference Board finds that, depending on company size, a cost in the range of one to several full-time employees could be required to manage the additional administrative burden.10 One of the key challenges for corporates is to determine the emissions of imported goods: according to a survey by the Chamber of Commerce (IHK) Stuttgart, only 3% of the companies surveyed expect to get the necessary data from their suppliers in the future.11

“CBAM is likely to affect new investment decisions”

Starting in 2026, importers will be obliged to purchase CBAM certificates for the emissions embedded in those goods. The sale and purchase of these certificates will take place over a common central platform – and these certificates are as of now expected to be unique and not tradable, explains Dragana Prodanovic, Carbon Emissions Trader at Deutsche Bank.

CBAM impacts global trade flows and companies’ administrative and finance processes, but how will it help to tackle climate change? “CBAM is expected to have a limited effect on global emission reduction,” says Mühlberger, as it only covers certain products and goods exported to the EU. Global cooperation on carbon prices would be better to accelerate the green transition globally, she adds. Yet, she acknowledges that coordinated policy action by the US, EU and China seems challenging in the current environment. “Any progress with respect to a global CO₂ price will only be part of a wider set of trade policy negotiations among the world’s major trading blocs,” she explains.

Voluntary carbon markets

Given that a global CO₂ price is nowhere near becoming a reality in the short-term and action on climate change is needed now, voluntary carbon markets will also have a role to play. As a reminder, these markets allow companies to offset their emissions by purchasing carbon credits from projects that remove or reduce greenhouse gas from the atmosphere. Morgan Stanley Research expects the carbon-offset market to grow from US$2bn in 2020 to around US$250bn by 2050.12

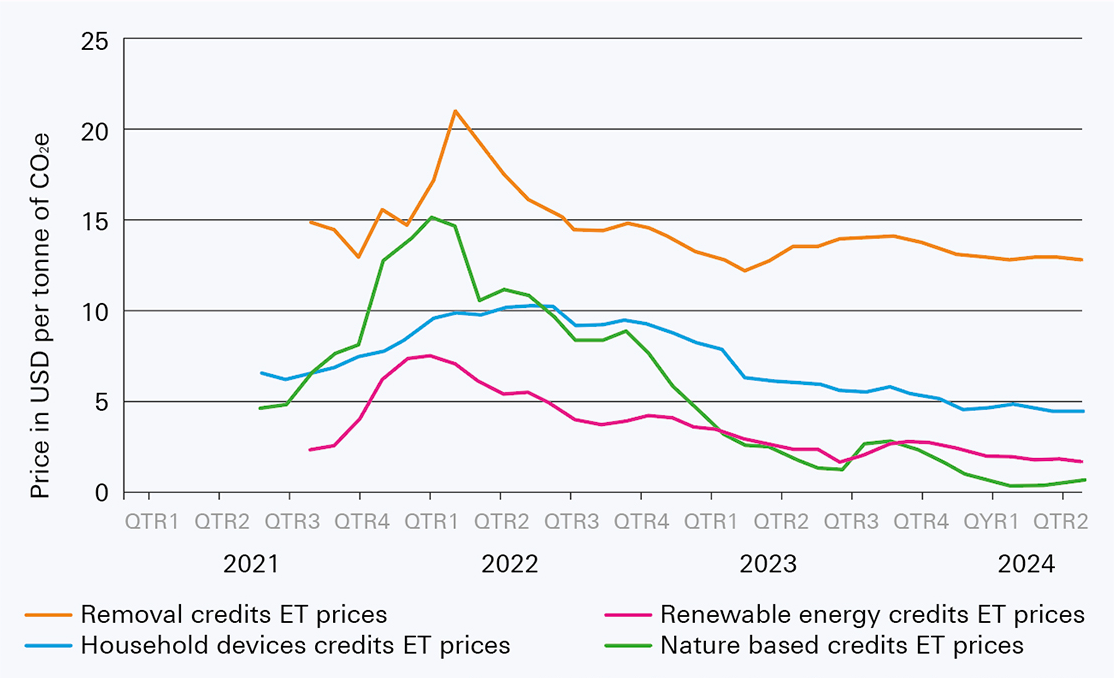

Yet, the market has come under severe pressure over the course of 2023 and 2024 as several large companies such as Shell, Nestlé and EasyJet have retreated from carbon offset schemes and prices for carbon credits collapsed. Their withdrawal stems partly from growing scepticism about the effectiveness of these projects, as well as a shift in strategy towards more direct measures to reduce emissions.13 As these markets are managed by private organisations without regulatory oversight, there are concerns around the actual climate benefits of projects qualified for offsetting.

Figure 4: Prices for carbon credits

Source: World Bank Report: State and Trends of Carbon Pricing 2024

This is all the more worrying as the purchase of carbon credits is no longer entirely voluntary. Airlines, for example, will soon be subject to carbon offsetting obligations. From 2027 on, all international flights will need to be offset as per the Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA).14 In the EU, this requirement will go beyond the airlines’ CO₂ allowances under the EU ETS.

"Voluntary carbon markets are still a nascent field that requires scale, but scale will require integrity”

To address the erosion in confidence in offsetting regimes, the Integrity Council on Voluntary Carbon Markets (ICVCM) – an independent governance body – launched 10 “Core Carbon Principles” (CCPs) in March 2023, defining high-quality credits with a focus on governance, emissions impact and sustainable development.15 "Voluntary carbon markets are still a nascent field that requires scale, but scale will require integrity,” says Lavinia Bauerochse, Global Head of ESG, Deutsche Bank Corporate Bank.

In May 2024, the world’s largest carbon-crediting program, Verified Carbon Standard (VCS, operated by Verra), met the CCP criteria. The ICVCM has also approved the Architecture for REDD+ Transactions (ART). Both schemes have made significant changes to the way they operate to comply with CCP, the ICVCM added. Now, five programmes, which have a 98% share of the voluntary carbon market, meet the principles.16

Despite these efforts to make the market more transparent, comparable and credible, carbon offsetting remains controversial. This is illustrated by the criticism following the decision of the Science-Based Targets initiative (SBTi) to allow the use of carbon credits toward companies’ scope 3 reduction targets, which cover up- and downstream emissions. While the organisation’s board of trustees considers “this step a way to accelerate the decarbonisation of value chains,”17 its own staff warn that the “use of offsetting mechanisms for scope 3 targets could completely nullify the already insufficient climate commitments of most companies”.18 Given that more than 5,000 businesses across regions and industries have set emissions reduction targets based on SBTi guidance, the organisation’s judgement is highly relevant for corporate net-zero journeys.

Internal carbon pricing

In addition to compliance regimes and voluntary carbon markets, there is a third dimension to creating a price for CO₂. “We see corporates introducing internal carbon pricing as a tool to achieve climate targets,” Bauerochse says. “It’s still in its early stages, but we expect this approach to gain importance. When a business sets an internal carbon price, a cost is typically assigned to each tonne of carbon emitted so this can be factored into business and investment decisions, incentivising efficiency and enabling low-carbon innovation,” she adds.

A pioneer in that space is Microsoft. Starting in 2012, the US tech firm implemented an initial carbon fee focused on scope 1, scope 2, and business air travel. “The proceeds from the fee provided funding for our carbon-neutral commitment at the time,” writes Elizabeth Willmott, Carbon Program Director at Microsoft. In 2020, the company began charging internal business groups for all scope 3 emissions and, in 2022, the carbon fee was redesigned to match the underlying costs of carbon abatement. “For example, the scope 3 business travel fee will increase to US$100 per metric ton of carbon dioxide equivalent in our next fiscal year to better support the purchase of sustainable aviation fuel,” Willmott adds.

In 2023, the company won the UN Global Climate Action Awards for this voluntary carbon tax model, which has helped to offset more than 1 million tons of carbon dioxide equivalent since 2012.19 It has also built a software solution to help track and report on GHG emissions and implement their own internal carbon pricing model.20

Compliance, voluntary, or internal: in the end, all carbon pricing approaches follow the same idea – making CO₂ emissions more expensive, to get people and businesses to act on climate change.

Sources

1 See un.org

2 See carbonpricingdashboard.worldbank.org

3 See icapcarbonaction.com

4 See icapcarbonaction.com

5 See icapcarbonaction.com

6 See climate.ec.europa.eu

7 See climate.ec.europa.eu

8 See climate.ec.europa.eu

9 See taxation-customs.ec.europa.eu

10 See conference-board.org

11 See ihk.de

12 See morganstanley.com

13 See carboncredits.com

14 See iata.org

15 See icvcm.org

16 See businessgreen.com

17 See sciencebasedtargets.org

18 See newclimate.org

19 See unfccc.int

20 See microsoft.com