21 October 2022

Winter is coming and what will bridge the energy gap created by the recent shutdown of Russian gas supplies and challenging emissions reduction targets, asks Deutsche Bank Research. flow shares some key points of a new report on Europe’s energy crisis

MINUTES min read

At the beginning of the Russia/Ukraine crisis, the EU said it would cut its reliance on Russian gas by two- thirds by the end of this year, making up the shortfall with liquified natural gas (LNG) from suppliers such as the US and Qatar and with renewable energy.1 It now looks as though the bloc will get through the coming winter with enough supplies – but only just – buoyed up by the gas reserves it raced to accumulate over the summer.

In other words, Europe is grappling with two big challenges at the moment: urgently weaning itself off Russian energy, particularly gas, and moving to a cleaner energy economy. At times, however, those two goals seem to be in opposition to each other.

Drawing on insights from Deutsche Bank Research’s special report European Energy Crisis 101: Ten green bottlenecks (October), by Adrian Cox, Jim Reid and Galina Pozdnyakova, this article sets out the ten bottlenecks they see holding Europe back as it urgently seeks to secure its energy supplies for 2023 and beyond. They reflect on how it is trying to do this at the same time as the bloc moves from coal to gas – classified by the EU taxonomy as a “transition fuel” – and from there to cleaner but less consistent alternatives.

The team highlight limits on current capacity, due to the limitations of Europe’s existing infrastructure and fuel options, as well as challenges for the future, such as red tape, a shortage of finance, skills and materials, and public opposition.

Bottleneck 1: Existing infrastructure

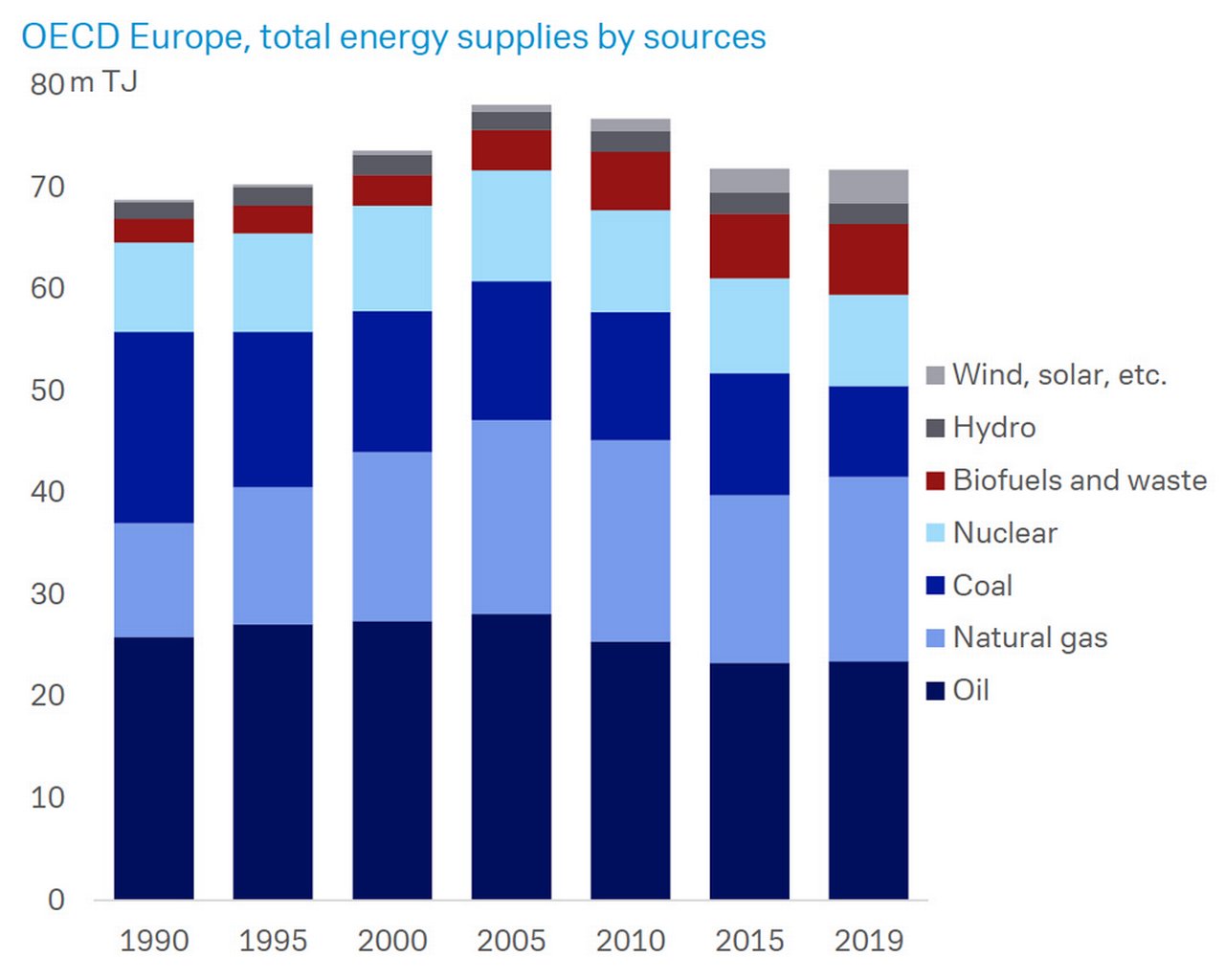

Natural gas accounts for almost a quarter of the EU’s total energy supply and fossil fuels overall still account for about three quarters of it.2 The biggest users cannot easily substitute gas for other sources – for example, gas is used by half of German homes for heating and by industry for process heating. Examples of these industries include chemicals and petrochemicals, metals, paper and food, and also as a raw material (feedstock) for chemicals and petrochemicals.

Figure 1: OECD Europe – total energy supplies by sources

Source: IEA World Energy Balances (2021), Deutsche Bank

Bottleneck 2: Limited liquefied natural gas capacity

Liquefied natural gas (LNG) is the closest substitute for piped natural gas. Europe’s LNG capacity has been running at close to flat-out since January. Germany and Eastern Europe largely lack the specialist infrastructure to import and re-gasify LNG. Most goes to the UK, Benelux, France, Italy and Spain.

Germany has arranged five floating LNG terminals, which should cover 20% of its current gas imports. The first three are due to start operating by early 2023.

The main exporters to Europe have been the US, Qatar and Russia, each providing around 20–25%; without Russia, alternative suppliers need time to ramp up liquefaction facilities. US LNG exports to Europe have more than doubled since last year, accounting for three-quarters of its LNG exports. However, there is competition for supplies and Europe must bid for supplies against the world’s biggest LNG importers – China and Japan.

Bottleneck 3: Bad year for other sources of energy

Gas use has actually increased in 2022 amid challenges for other sources.

France’s nuclear production is set to fall to the lowest in three decades due to maintenance on half of its ageing reactors. Normally Europe’s biggest power exporter, it has become a net importer. France has said state-owned provider EDF aims to end the closures in coming months.

Germany has delayed its longstanding plans to phase out its last three nuclear plants by year-end. Europe’s hottest ever summer caused demand for cooling to surge, it diminished hydro power and sent the Rhine falling to near record lows, disrupting water transport of materials such as coal.

Ten EU countries had phased out coal as of 2021 and most will do so by 2030. Germany has agreed a plan to phase out coal by 2038, ideally earlier, but this year has fired up mothballed coal plants to meet energy demand.3

“What is critical in the green transition of the power sector … is to ensure there is enough flexible capacity to balance intermittency”

Bottleneck 4: Intermittent renewables supply

Wind and solar supply are inconsistent. In Germany they supply between less than 10% and up to 100% of hourly power demand, depending on the weather.

The intermittency point is developed further by Deutsche Bank Research utilities analyst James Brand in the Podzept podcast featured at the end of this article.

“If you have a wind farm it only runs when the wind is blowing and if you have a solar power, only when the sun is shining. Over the winter when not very sunny or when there are two or three days of low wind, there is a shortage. What is critical in the green transition of the power sector so that it does not go wrong is to ensure there is enough flexible capacity to balance that intermittency. Slightly ironically, the answer to that is generally perceived to be gas...this is what needs to happen – particularly in Germany as it looks to phase out coal and nuclear.”

Electricity can’t yet be stored at scale and at low cost, so renewables cannot be the prime source to meet baseload demand for now.

Europe continues to invest in gas, the easiest fuel to fire up and down. Gas CO2 emissions are also half as much as hard coal. Germany depends on coal/lignite for 34% of electricity generation, by far the most reliant major economy. It will need to ramp up gas, now 10%, to bridge the gap.

Distribution of renewable power is constrained by the existing infrastructure. This needs to be upgraded to be able to back up intermittent supply, strengthen transmission and distribution networks and onboard decentralised sources.

Bottleneck 5: Europe’s sticky energy consumption

Europe’s overall energy use has changed little over recent decades as improved efficiency has been offset by greater consumption in areas such as excess heating and cooling.

How does the response compare with past crises? Policies in the 1970s included rationing for households and industry; this time the policy focus is on cushioning monetary losses rather than cutting demand.

Industry cut consumption over the summer, for example it declined 20% in Germany, amid falling demand. Households have made only moderate weather-adjusted cuts in consumption this year and scope for winter cuts is limited.

Germany is the best insulated country in the world, leaving little low-hanging fruit, while the cost of insulating leakier homes in Southern and Eastern Europe may be prohibitively expensive.

Bottleneck 6: Financing

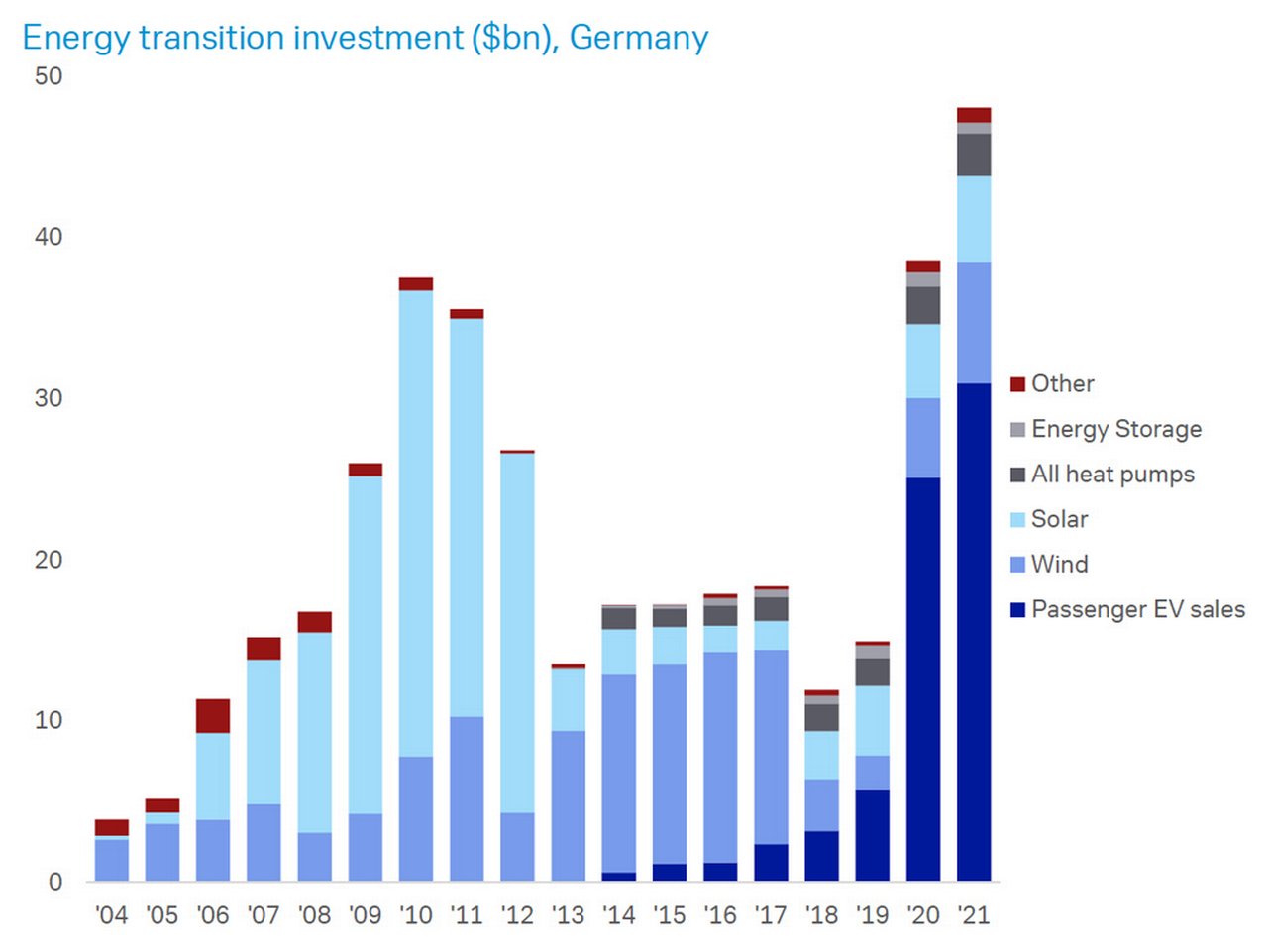

Figure 2: Energy transition investment (US$bn), Germany

Source: BloombergNEF, Deutsche Bank

LNG terminals, regasification facilities and distribution grid projects are expensive and interest-rate sensitive, like bonds. Yields are rising, economic activity is slowing down, and countries are squeezing electricity suppliers, which may limit cash flows for necessary investments.

Bottlenecks are widespread. They are evident at:

- The state level, with limited budgets and difficult trade-offs;

- The corporate level – for example the transformation of production processes in energy-intensive industries; and at

- The household level – for example the costs of electric heat pumps and insulation.

Switching to clean energy by 2050 would cost US$5.3trn, according to a report publishing in April 2022 by BloombergNEF.4 This capital expenditure will be front-loaded as renewables have high initial fixed costs and lower operating costs later on. In Germany, almost 200GW of new renewables are targeted by 2030. This means that 25–30GW of gas capacity would be needed to deal with intermittency (see Bottleneck 4 above).

“The main challenge to overcome is scalability”

“A massive expansion of renewable power is needed. While financing structures in this area are established and the risks well understood, the main challenge to overcome is scalability,” adds Lavinia Bauerochse, Global Head of ESG at Deutsche Bank Corporate Bank. She also makes the point that investment is needed in “storage, hydrogen and the electrification of processes, which currently rely on fossil fuels”.

Bottleneck 7: Red tape

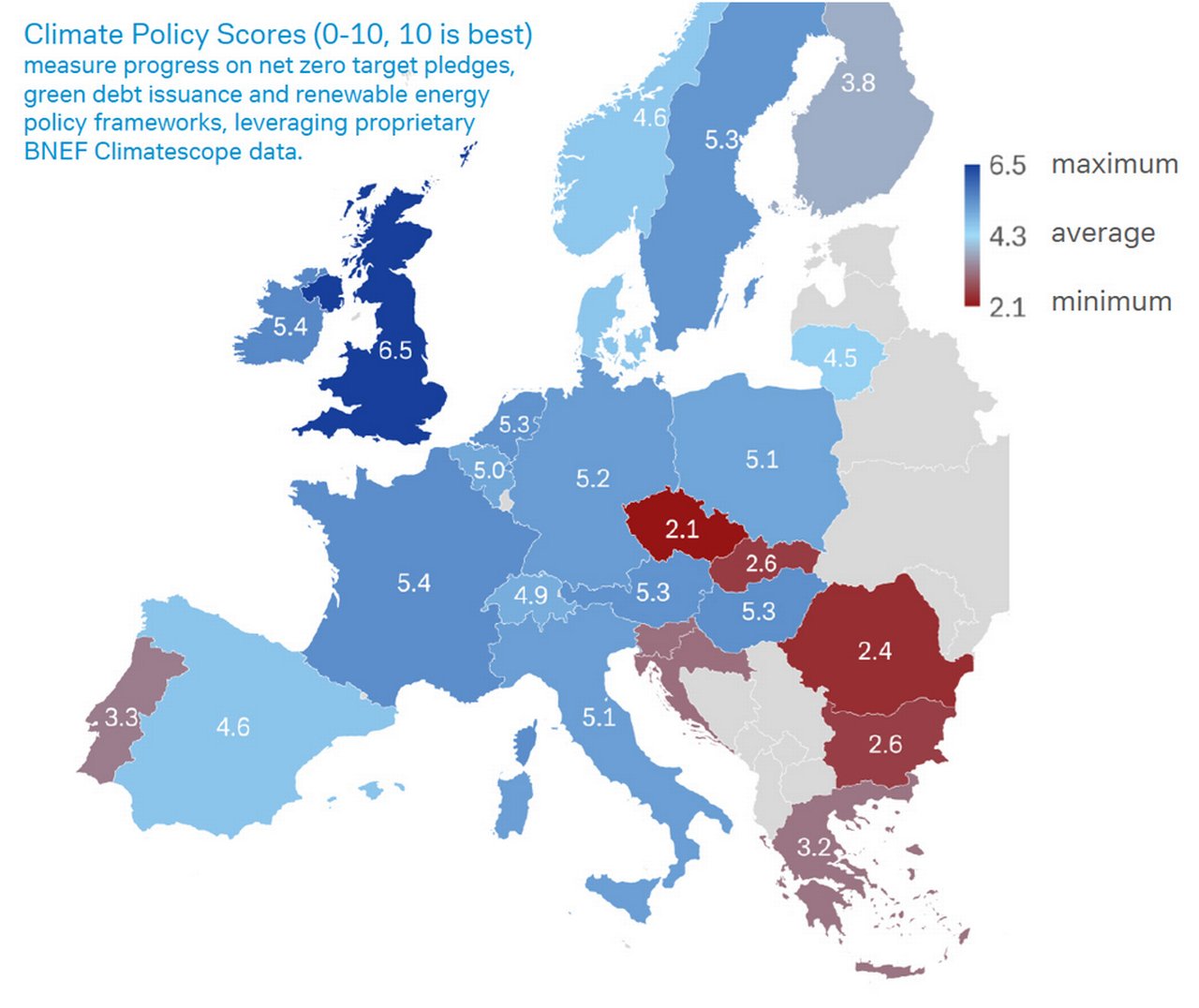

Figure 3: Climate policy scores

Source: Bloomberg Finance LP, Deutsche Bank

Long, complex and opaque administrative processes, such as bottlenecks in building authorities, hold up rollouts of energy projects. Renewables are also often not integrated into spatial and environmental planning. There are also political, market structure and grid access issues, along with customs delays for imports of materials such as solar panels.

“There are a lots of long-term fixed price contracts that are on offer from governments to utility companies wanting to build renewables…but there are constraints around planning, particularly in Germany, and around supply chains,” explains Deutsche Bank Research’s Brand.

What is being done to speed things up? Many of the EU plans address cutting red tape and creating a pan-EU market. Germany’s Onshore Wind Energy Act, passed in July 20225, focuses on speeding up planning and approval processes. It aims to create binding land-use targets and to increase the area of land available to 2%.

“Reducing the complexity of approval procedures at a country and EU level would be a key enabler to achieving the energy transition and renewables build-out,” reflects Bauerochse.

Bottleneck 8: Scarce commodities

Source: IMF, European Commission (2020), Ifo Institute, Deutsche Bank

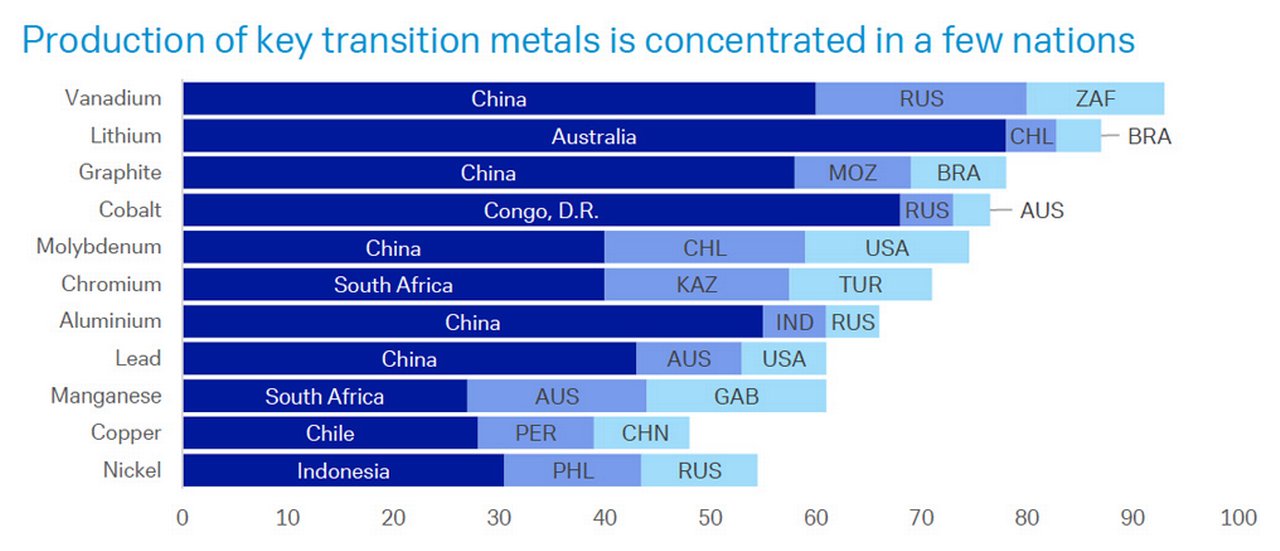

Low-carbon technologies are more metals-intensive than traditional technologies.

Europe’s dependence will shift from fossil fuels to metals and Rare Earth Elements (REE) that are concentrated in just a few nations.6 For example, China accounts for more than half of the global market in vanadium, graphite and aluminium; Australia is dominant in lithium; and the Democratic Republic of Congo in cobalt.7

Copper, dominated by Chile, is particularly important for wind and solar energy, while an electric car contains twice as much copper as a conventional one. Current mines are close to exhaustion – and global demand for copper is almost two times the supply. For nickel it is three times and for vanadium, cobalt and graphite it is around five times.

“Given the expected shortage of supply, the question arises how long-term access to these and other critical commodities can be ensured. Germany will be particularly challenged as these commodities are not available locally and must be sourced from countries such as Congo, China, and Chile,” commented the Deutsche Bank white paper, How to ensure commodities security in a volatile world (April 2022).

Bottleneck 9: Skills shortage

Renewable expertise is concentrated in a few companies and installation, such as attaching solar panels onto roofs, is labour intensive.

BloombergNEF estimates that Europe had imported a third more solar panels from China by July than it will be able to install all year, due to insufficient labour. The bloc will have to manage an employment transition for many of its 7.5 million workers in energy, or 2.4% of employment, including 700,000 supplying coal, oil and gas and 1.4 million working in power generation.

Separate figures show 1.3 million people were employed in renewables in the EU in 2020. Furthermore, to build its nuclear capacity and diversify away from Russia, Europe may need to turn to overseas producers including China as one of the leading players in nuclear technologies.

Bottleneck 10: Public opinion

More than 85% of EU citizens say they support ambitious targets for renewables and would support new wind and solar projects near where they live.

But when it comes to installations near their backyards, public opposition to unsightly wind turbines and sprawling solar farms is one of the main obstacles to expansion in a continent with limited available land. These concerns have dramatically slowed installations in Germany, for example.

Europe is estimated to have larger shale gas reserves than the US, mostly in Poland and France. But it has no commercial production, due to higher population density, regulations and public opposition to fracking – the same process the US uses to extract the gas it sells to Europe.

And as for storable “green hydrogen” – this is some way off. Without enough renewable capacity to generate the amount needed and doubts about how easily pipelines can be retrofitted to carry it, it does not look like it will be coming on stream anytime soon.

Podzept podcast: Europe’s energy crisis

To hear more discussion of Europe’s energy crisis, listen to Deutsche Bank’s Adrian Cox, Marion Mühlberger, and James Brand in their podcast where they discuss:

- What is the European response? There has been a patchwork of national support measures and three milestone packages.

- Will there be enough gas over winter? Probably yes, but it will be a balancing act. Household consumption will need to be closely monitored as the weather gets colder.

- What about the phasing out of Russian gas completely – is that possible?

- What are the challenges of the broader energy transformation? There is a lack of financing and constraints at the corporate and the household level.

- What are the challenges with transitioning to renewables? Is hydrogen the solution?

Tune in and listen to the podcast here

Deutsche Bank reports referenced

European Energy Crisis 101: Ten green bottlenecks (October), by Adrian Cox, Jim Reid and Galina Pozdnyakova

Sources

1 See reuters.com

2 See "Towards 2050: the case for gas" at flow.db.com

3 See reuters.com

4 See about.bnef.com

5 See cleanenergywire.org

6 See "Why its time for a new look at rare earths" at flow.db.com

7 See "How to ensure commodities security in a volatile world" at corporates.db.com

Sustainable finance solutions Explore more

Find out more about our Sustainable finance solutions

Stay up-to-date with

Sign-up flow newsbites

Choose your preferred banking topics and we will send you updated emails based on your selection

Sign-up Sign-upYou might be interested in

Sustainable finance, Trade finance and lending

How to manage transition to net-zero How to manage transition to net-zero

As economies around the world pledge their commitment to net-zero emissions by 2050, companies need to step up their decarbonisation plans. Deutsche Bank’s Lavinia Bauerochse reflects on how this is changing the role of banks and why transition is becoming a core element in client conversations

Sustainable finance, Trade finance and lending

Towards 2050: the case for gas Towards 2050: the case for gas

The COP26 summit saw governments commit to achieving Net Zero by 2050, but this will prove “incredibly difficult to achieve”, a recent Deutsche Bank Research report concludes. flow’s Clarissa Dann examines why its analysts believe that although the world’s appetite for coal and oil must be cut, gas plays a vital role in keeping the lights on

Corporate Bank solutions

How to ensure commodities security in a volatile world How to ensure commodities security in a volatile world

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has put a spotlight on Europe’s uncomfortable dependencies. Securing access to important commodities is key to economic resilience, as well as digital and sustainable transformation – and this requires rethinking sourcing strategies as our new flow special white paper outlines