India has pledged to cut its carbon emissions to net zero by 2070 – seemingly a less stringent target than those set by other major economies. However, for an emerging economy of 1.4 billion citizens where energy demand keeps rising, strong partnerships, innovation and finance are key to making this happen, reports Deutsche Bank’s Sreenath Vakkaleri

MINUTES min read

1.4 billion

28.7

1/6

At the Glasgow COP26 climate summit in November 2021, India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi committed his country to achieving net-zero emissions by 2070 – 20 years later than similar self-imposed targets set by North America and Europe and 10 years after China.1

“By 2030 India will take its non-fossil energy capacity to 500 GW; meet 50% of its energy requirements from renewable energy and reduce the total projected carbon emissions by one billion tonnes. By 2030, it will reduce the carbon intensity of its economy by more than 45%. and by the year 2070, India will achieve the target of net zero,” he said.2

Net zero roadmap

While climate change activists might wish for a swifter path to net zero, the pledge has huge implications for a country of nearly 1.4 billion people, or one-sixth of the total global population. Three decades have passed since India’s government set up the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE) to help transition the country to renewables such as wind power, small hydro, biogas and solar power but progress has been slow. An October 2021 study published by Asian non-profit research institute the Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW)3 concluded that to meet the 2070 target India must achieve five main de-carbonisation goals:

- Phase out coal in the industrial sector by 2065;

- Phase out all other use of coal by 2060;

- By 2050 reach 1,700 gigawatts (GW) of solar-based generation capacity;

- By 2050 reach 557 GW of wind-based generation capacity; and

- By 2050 expand to 68 GW of nuclear-powered generation capacity.

The CEEW study also reviewed India’s transportation sector and suggested market share targets for 2070, which would see:

- Electric cars account for 84% of all car sales;

- 79% of trucks electric with the remainder fuelled by hydrogen-power;

- Biofuels blends providing 84% of the petrol for cars, trucks and airlines.

Another study by Standard Chartered calculating the investment required to transition eight major emerging market economies to net zero puts the cost for India at US$12.4trn, a figure requiring local and overseas investors in addition to government funding.4 There are hopes that major technology developments in carbon capture and sequestration can shorten timelines and trim the formidable cost.

GDP growth

Deregulation in 1991 and economic reforms have galvanised the Indian economy which, until the pandemic, averaged annual growth of nearly 7%. The Covid-19-induced contraction was sharp but short-lived and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) expects India’s GDP to exceed 8% in 2022. For more information on the countries’ macro-economic development, see also the recent flow article India’s gateway to growth.

Modi’s government aspires to maintain this pace across all sub-sectors of the economy while moving many workers away from agriculture and subsistence agriculture to other sectors. As The Economist noted in its 14 May issue: “Even if India manages a growth rate of nearer 6% than 9%, that would be nothing to sneeze at. It would make India the world’s third-largest economy by the mid-2030s, at which point it would contribute more to global GDP each year than Britain, Germany and Japan combined.”5

Improving access to and availability of electricity is central to these goals, together with better information and access to resources and services; education and literacy; water/sanitation; and healthcare.

Access to safe drinking water

Until now, limited access to safe drinking water in rural and urban areas was a major burden on the economy and public health. Although home to one in six of its population, India has only about 4% of the world’s freshwater resources. However, the picture has rapidly improved since the government’s launch of its flagship Jal Jeevan Mission in August 2019. As summarised in Figure 1, over the initiative’s first 32 months 49.1% of functional households have been connected to safe drinking water6.

Figure 1: Functional Household Tap Connection (FHTC) as at 30.03.2022

Source: Jal Jeevan Samvad (April 2022)

Power demand – and supply

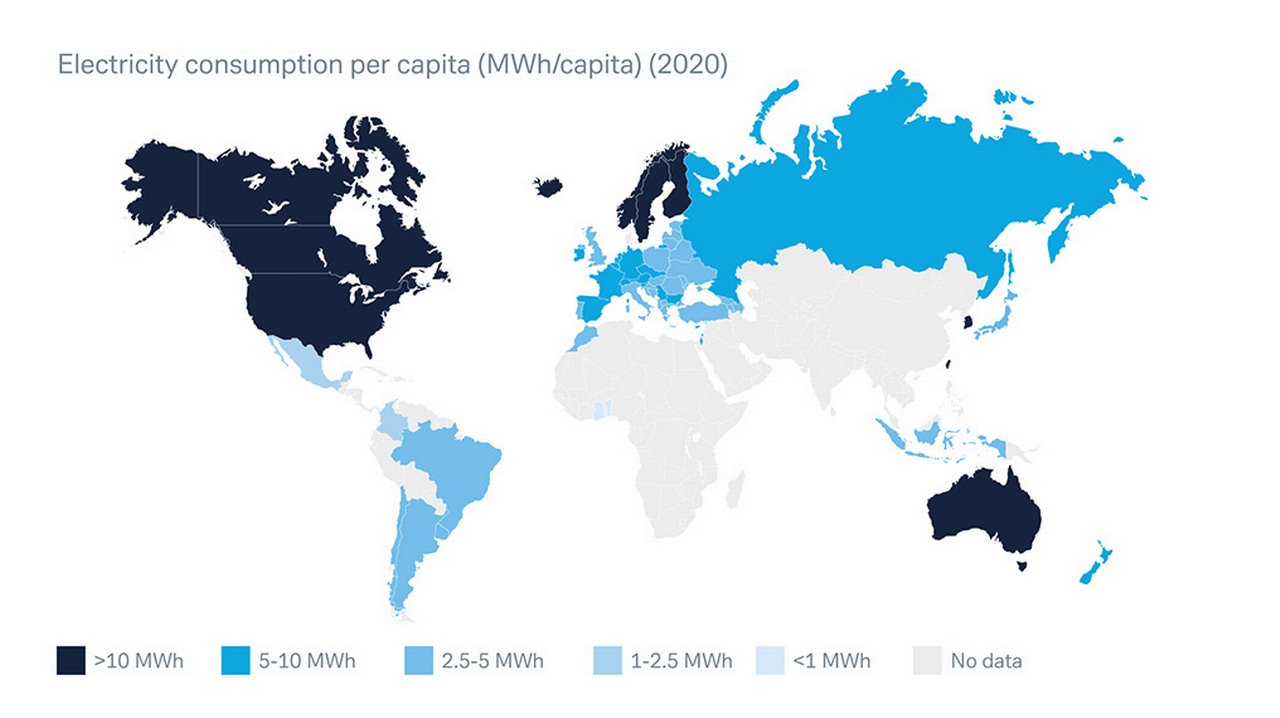

Figure 2: Total electricity consumption

Source: The International Energy Agency

According to the International Energy Agency’s (IEA) 2021 Atlas of Energy the world’s two biggest economies account for more than 45% of global electricity consumption (see Figure 2), with China (28.5%) and the US (16.8%) followed by India (5.7%).

However, measured by electricity consumption per capita the rankings differ significantly. In 2019 energy consumption in thousand kWh/capita was 12.74 for the US, 5.12 for China and just 0.99 in India. On a per capita basis, India’s power use is less than half the world average, despite doubling since 2000. Over the past decade, nearly 50 million new users have been connected to electricity annually and more than 900 million citizens since the millennium to achieve near‐universal household connectivity by 2019.

Power demand is expected to keep rising, with a growing population adopting more appliances. An International Energy Authority (IEA) forecast7 suggests India will account for 25% of the projected global increase in the period 2020–2040.

59.%

India is the world’s third largest producer of power and as of January 2022 had installed generation capacity of 395.1 GW8. Fossil fuels still account for three-fifths (59.7%) of this figure, with the balance comprising large hydro (11.8%), renewable energy sources (28.5%) and nuclear (1.7%). The CEEW study9 suggests that the country’s power capacity needs to maintain annual growth rate of 7% between now and 2050 for the sector to achieve the net-zero target.

Building non-fossil energy capacity

Modi’s targets commit India to raising its non-fossil energy capacity to 500 GW by 2030, implying a four-fold growth of operating assets over the 2020s. However, already the 2022 target of 175GW (100GW of solar power, 60GW of wind, 10GW of biomass and 500MW of small-scale hydropower) already appears likely to fall short by 25%–30% (excluding large hydro projects) due to a combination of Covid-19-led disruptions, delays in sourcing, price volatility for solar modules, logistics/shipping constrictions and developers’ financing challenges. Despite delays, an active pipeline of projects is under construction or at tendering stage.

A December 2021 study, Least Cost Pathway for India’s Power System Investments through 2030 by the US-based Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory noted that “achieving India’s goal of 500 GW of non-fossil capacity (predominantly renewable) is the least-cost and most economical pathway to meet India’s rising electricity demand, while safeguarding grid reliability, as long as renewable energy (RE) can be supplemented by flexible resources.” 10

The Ministry of New and Renewable Energy wants India to be a global renewable outperformer in the 2020s with non-hydro renewables capacity increasing by an average 10% annually between 2021 and 2030. This looks achievable, as The Economist noted on 14 May: “there is a renewable energy investment spree: India ranks third for solar installations and is pioneering green hydrogen”. On the downside: “despite surging private investment in renewable energy, the state-owned firms that distribute electricity are bankrupt and supply is unreliable.”

Energy savings via LEDs

India has also achieved energy savings in recent years from a policy push to deploying energy‐efficient appliances. In all but three states, light-emitting diodes (LEDs) are now used in over 80% of households. The government’s flagship Unnat Jyoti by Affordable LEDs for All (UJALA) scheme, launched in 2015, saw the deployment of 366m LEDs while the LED Street Lighting National Programme has led to the installation of more than 10 million LED smart streetlights by the Energy Efficiency Services Limited, a government‐owned energy services company. The government estimates that annual energy savings of about 54 terawatt‐hours (TWh) have been achieved through these measures.

Both the growth rate and level of investor interest in renewables have established India as a key player globally. The UN Environment Programme (UNEP) report Global Trends in Renewable Energy Investment 2020’ shows that pre-pandemic, India attracted investments worth INR4.7trn (US$64.2bn) in renewable energy products from 2014 to 2019. In March 2021, the US Agency for International Development (USAID) and the US International Development Finance Corporation (DFC) announced a US$41m loan guarantee programme to support Indian SMEs’ investment in renewable energy.11

The Production Linked Incentives (PLI) scheme

Production Linked Incentive (PLI) schemes were first introduced by India’s government in March 2020, focusing on three fast-growing sectors: mobile manufacturing and electric components; pharmaceuticals; and medical device manufacture.

PLI addresses solar modules and solar cells, which typically represent 80% of set-up costs for a solar plant. Under the scheme, the government has announced a mix of financial incentives to promote manufacturing of photovoltaic (PV) modules and solar cells in India and protectionism to discourage imports from China – it proposes levying 40% custom duty on solar modules and 25% on solar cells.

The PLI scheme allocation announced on 1 February in the Union Budget 202212 is expected to add further investment of INR35bn for solar PV cells and modules manufacturing in India, accelerating the reduced dependence on imports and making the 2030 renewable energy targets achievable. The new PLI funding will facilitate manufacturing capacity of 40 GW solar modules by RLI, Adani Group, Tata Group and others. Manufacturers will receive PLIs over five years post-commissioning of solar module plants. Nearly 55GW annual production of solar modules – or 275GW over the period – will be funded.

India’s multinational conglomerate Reliance Industries (RIL) announced in January 2022 that it will invest INR5trn (US$80bn) in the state of Gujarat over 10–15 years to set up a 100GW renewable energy power plant and green hydrogen ecosystem.13 RIL will add a further INR600bn for building manufacturing facilities for new and renewable energy equipment.

Other initiatives

One regular criticism of renewables like solar and wind is their intermittency. However, when ReNew Power, the country’s largest renewable energy company won India’s first e-Reverse Auction in May 2020 for a 400MW renewable energy project it pledged round-the-clock supply of green power. ReNew won the bid on a first-year tariff of INR 2.90 per kilowatt hour with a 3% annual escalation for the first 15 years of the 25-year term of the Power Purchase Agreement (PPA). Adani Green Energy has also won the bid for firm renewable power at INR 2.96 per unit, also well below the average cost of power supply.

In addition to committed funding of INR1.97trn (US$25.4bn) over the next five years to develop schemes that boost domestic solar manufacturing, the government also set up the Solar Energy Task Force, through the Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry (FICCI), to develop its domestic solar manufacturing industry but with the wider aim of helping Indian solar manufacturers compete globally.

Since 2011, it has been mandatory for all power procurement to be made through the tariff-based competitive bidding (TBCB) mechanism, which ensures the power procurer gets the best possible tariff, with no distinction between public or private power suppliers. Generally, the TBCB process is routed through government entities such as the Solar Energy Corporation of India (SECI) and NTPC (formerly National Thermal Power Corp) to eliminate price risk and volume risk for the power suppliers. This is preferable to the Feed-in Tariff (FiT) mechanism where price is negotiated between procurer and supplier.

As part of the auction mechanism, the government aims to waive transmission charges for renewables projects to encourage interstate power trading. This will be critical to the ongoing expansion of India’s wind sector, so states that are building up large installed wind capacity bases can find an outlet for the excess power generated by trading with states with a power deficit.

Case studies

In 2021, Deutsche Bank’s Trade Financing and Lending (TF&L) India and the Corporate Bank began stepping up support for both multinational (MNC) and limited liability company (LLC) clients on their funded-based and non-funded-based requests. These include:

- Letters of credit (LCs) to support import of equipment and local sourcing of equipment through construction;

- Factoring and structured AR solutions to manage developer and equipment vendor demand for financing/liquidity with/without recourse including trades supported by ECA;

Clients have sought longer-term financing, such as including project finance on a non-recourse basis through the initial construction phase and Deutsche Bank has helped several companies by refinancing solar PV operational projects on a non-recourse and on-balance sheet basis and supporting financial institution-backed fund-based and non-fund-based facilities for projects during their construction phase.

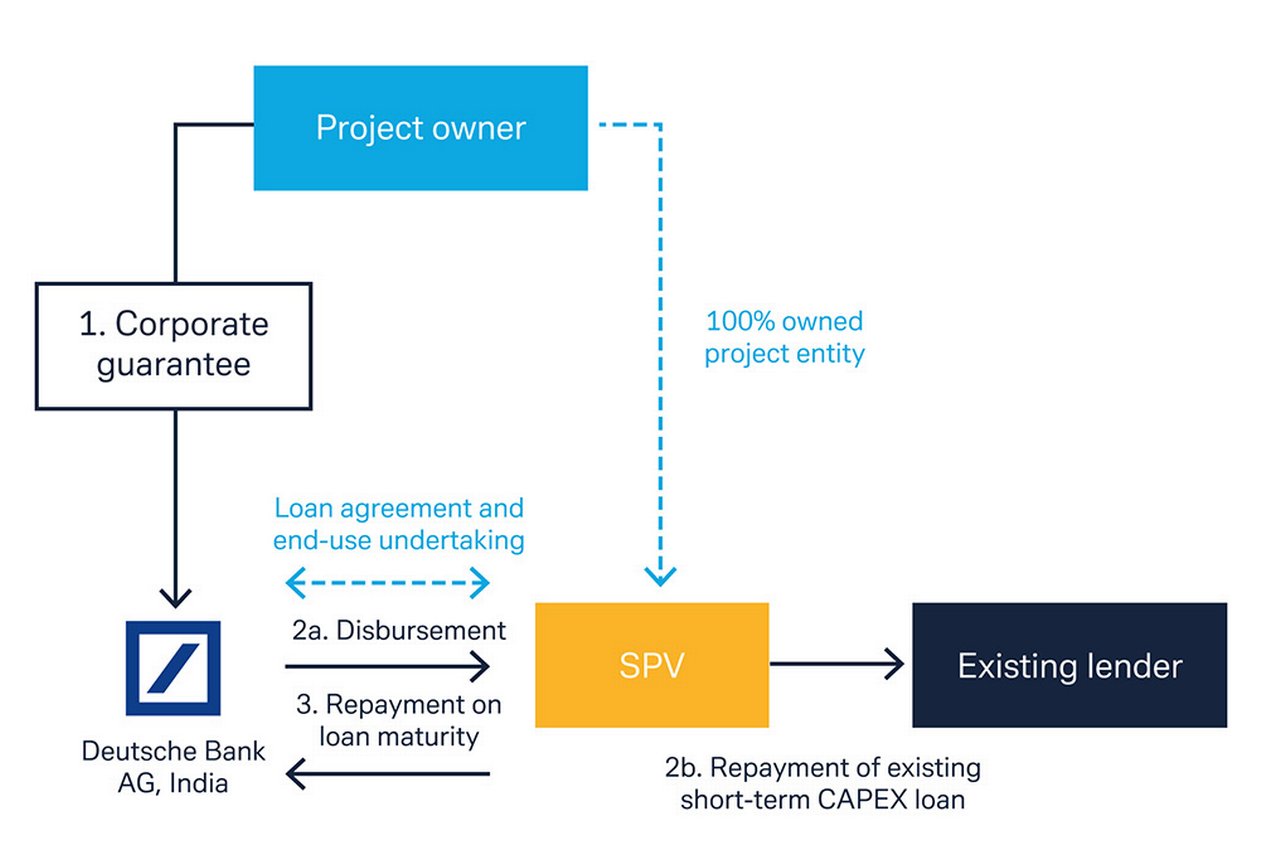

Medium term capex loan for solar power project

Figure 3: Summary of capex loan for solar power project

Deutsche Bank extended capex financing for a 50MW solar power project in India with tenor up to five years. This is further backed by a corporate guarantee and security over the project company. See Figure 4.

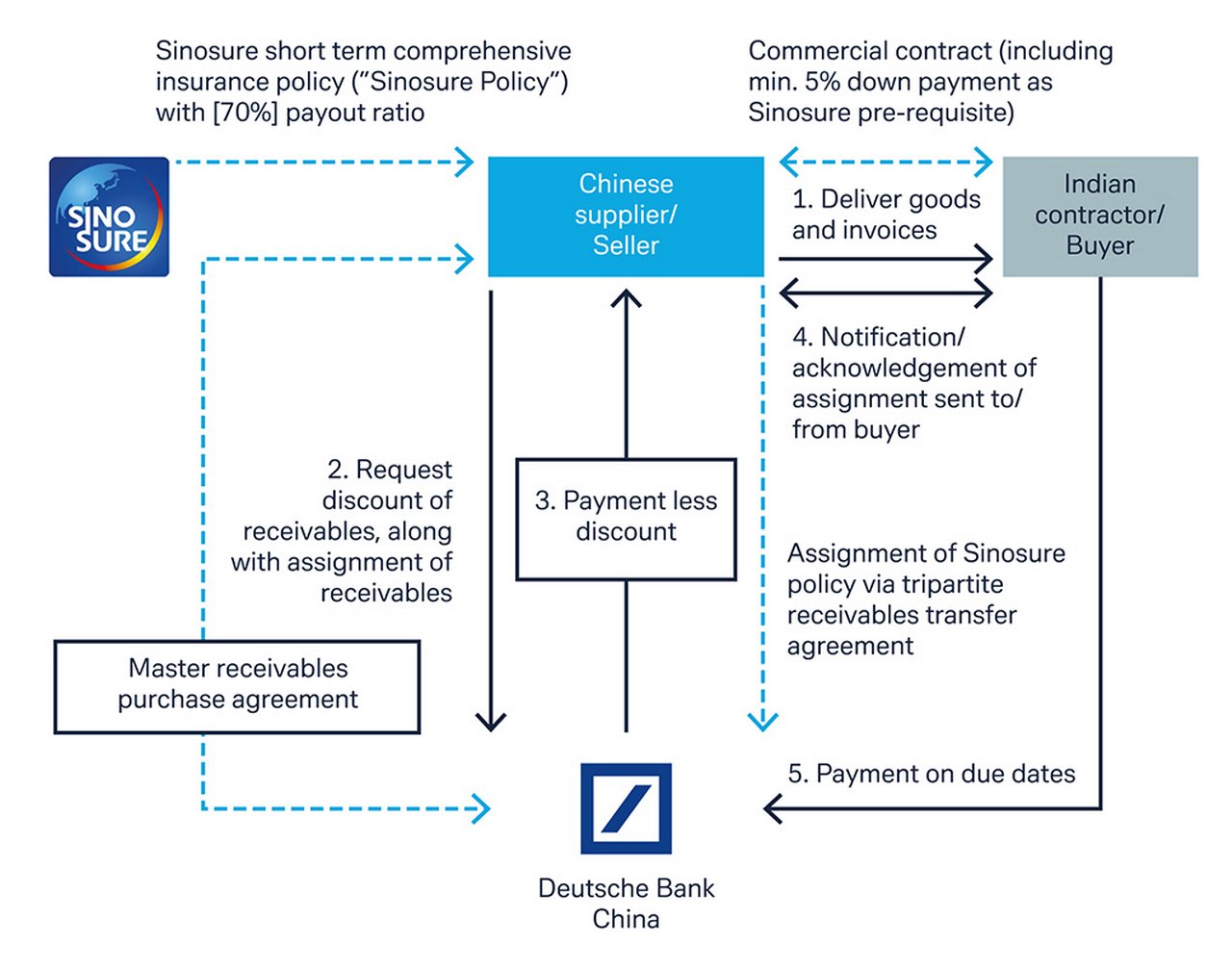

Figure 4: Sinosure short-term (ECA) backed AR purchase programme

Deutsche Bank provided a revolving account receivables (AR) facility to a Chinese solar panel manufacturer to support their supply of solar PV modules to India-based engineering, procurement and construction (EPC) contractors located. Guaranteed by the Chinese export credit agency Sinosure, this supports working capital requirements arising from short-tenor trade flows with China and improves the seller’s competitive position by providing their buyers with extended payment terms.

Delivering net zero

An emerging economy such as India, with a per capita income of US$1,92814 (or US$8,100 in purchasing power parity (PPP) terms), is classified as a “lower middle income” country at about 15% of the global average and the country still has much to do towards lifting its people out of poverty. Its population – 1.4 billion and forecast to peak at 1.5-1.6 billion in the 2040s – presents GDP growth opportunities (the average age is 28), it nevertheless presents colossal challenges to the net zero target. But it must get there – the world cannot afford for it not to.

Sreenath Vakkaleri is Head of Structuring, Trade Finance and Lending India, Deutsche Bank

Sources

1 See https://bbc.in/3t6n7NV at bbc.com

2 See https://bit.ly/3wWhNgZ at economictimes.indiatimes.com

3 See Implications of a Net-Zero Target for India’s Sectoral Energy Transitions and Climate Policy, Working Paper | October 2021 Vaibhav Chaturvedi and Ankur Malyan

4 See https://bit.ly/3lZ8d85 at sc.com

5 See https://econ.st/3N64tO4 at economist.com

6 See https://bit.ly/3N3y2zN at jalshakti-ddws.gov.in

7 See India Energy Outlook 2021, The International Energy Agency

8 See https://bit.ly/3M1Q6ck at powermin.gov.in

9 See https://bit.ly/3t5y7uE at ceew.in

10 See https://bit.ly/3PPG2pL at eta-publications.lbl.gov

11 See https://bit.ly/3M3IWUI at financialexpress.com

12 See https://bit.ly/3xcp9i1 at economictimes.indiatimes.com

13 See https://reut.rs/3NOjVhx at reuters.com

14 See Current USD (as of Feb 2022); Source: World Bank

Sreenath Vakkaleri

Head of Structuring, Trade Finance and Lending India, Deutsche Bank

Sustainable finance solutions Explore more

Find out more about our Sustainable finance solutions

Stay up-to-date with

Sign-up flow newsbites

Choose your preferred banking topics and we will send you updated emails based on your selection

Sign-up Sign-upYou might be interested in

Sustainable finance, Trade finance and lending

Towards 2050: the case for gas Towards 2050: the case for gas

The COP26 summit saw governments commit to achieving Net Zero by 2050, but this will prove “incredibly difficult to achieve”, a recent Deutsche Bank Research report concludes. flow’s Clarissa Dann examines why its analysts believe that although the world’s appetite for coal and oil must be cut, gas plays a vital role in keeping the lights on

SUSTAINABLE FINANCE, TRUST AND AGENCY SERVICES

Paving the road to net-zero Paving the road to net-zero

Finance for critical ESG-aligned infrastructure is underway but the journey has only just begun. In an interview, Deutsche Bank’s Claire Coustar, Emily Kreps and Thalia Delahayes share insights on how carbon pricing, the focus on natural capital and regulation are shaping project finance

Paving the road to net-zero MoreCash management, flow case studies

Boosting treasury in India Boosting treasury in India

German vibrant science and technology company Merck has turned its treasury business in India inside out. Jörg Bermüller tells flow’s Desirée Buchholz how his team reduced FX risks, optimised liquidity and streamlined processes in an award-winning project with Deutsche Bank