26 March 2021

The just-published 14th Five-Year Plan is less concerned with growth targets than going it alone and making China self-reliant on goods such as computer chips, report flow’s Graham Buck and Janet Du Chenne

MINUTES min read

As March 2021 began, many countries were looking back ruefully on a full year of economic disruption and restrictions imposed by the Covid-19 pandemic. By contrast, the world’s second-largest economy was looking forward. China’s 14th Five-Year Plan (FYP) was published on 5 March and approved six days later.

According to the international weekly Nature1, scientific and technological self-reliance is at the centre of the latest FYP and reflects the tensions of recent years with the US – particularly over trade – and other Western nations, extending into the realm of science. It “sets out China’s vision for social and economic development over the next half decade, and … also aims to create closer ties between academia and industry, and to improve evaluation of the results of such collaborations”.

As The Economist explained in its 4 March article ‘What is China’s five-year plan?’, China’s FYPs were strictly implemented in the era (1949-1976) of Mao Zedong, when “the Communist Party set production quotas – for instance, for steel and grain – that work units had to meet. This central direction and, often, misdirection squandered resources, leaving much of the country impoverished.

“In the 1980s, as the party loosened its grip on the economy, it also became more relaxed about the FYPs. Rather than rigid agendas, they became more like manifestos for how the party wanted to steer the country. Yet these manifestos still pack a punch”.

The latest plan would be scrutinised, the paper added, for more on the “dual circulation strategy” first introduced by President Xi Jinping last year, which basically looks to lessen China’s dependence on global markets (international circulation) while developing its capacity to self-produce what it wants and needs (domestic circulation). China “has come a long way since the Maoist era, but the desire for self-reliance echoes through the decades”.

The “19 parts, 65 chapters, and 20 main quantitative targets” of the 14th FYP were analysed by Deutsche Bank Research’s Chief Economist for China, Yi Xiong and Research Associate Grant Feng in their 17 March white paper China Macro: The 14th Five Year Plan (1): 20 Targets for 2025. They describe the published document as an “overarching blueprint” that sets out China’s goals and priorities for the years 2021 to 2025 and will be followed by individual five-year plans from various ministries and regions.

“China has a good record in achieving most, if not all, of the Five-Year Plan targets.”

The 20 main quantitative targets contained in the new FYP will guide the policymaking process over coming months, they add and also help the government track its implementation over the next five years and adjust its policies as and when necessary. China has “a good record in achieving most, if not all, of the FYP targets” – although 20 is fewer than the 11th, 12th and 13th FYPs, which contained 23, 24 and 25 targets respectively.

A softer growth target

The 14th FYP was subsequently analysed by The Economist’s 13 March issue in the leader ‘A confident China seeks to insulate itself from the world’, which noted that although the document refrains from mentioning the US by name “every official knows that competition with America looms large in China’s strategies”.

So while the 13th FYP outlined how a peaceful multilateral world would benefit China, the new edition highlights the dangers of “hegemonism”. The paper commented that geopolitical uncertainties help explain what many regard as the most striking element of the 14th FYP, “its omission of one target that was a centrepiece of previous plans: average yearly growth. Instead, it states that growth targets will be set each year, depending on conditions. China is wary of committing itself when it does not know whether America will choke off its supply of high-end semiconductors, among other things”.

Xiong and Feng also spot the absence of any five-year GDP target at the start of their white paper, adding that the previous one – 6.5% per year for the period 2016-2020 – was missed as actual GDP growth for the period averaged 5.77%. While Covid-19 was the main culprit, had it not happened China would have met the target but “only by a very thin margin”. And in addition to omitting a growth target, a previously-discussed goal of doubling GDP and income by 2035 has been dropped from the 14th FYP. The authors also regard the 2035 goal of China as a middle high-income country to be “more of a vision rather than a precise, quantifiable growth target”.

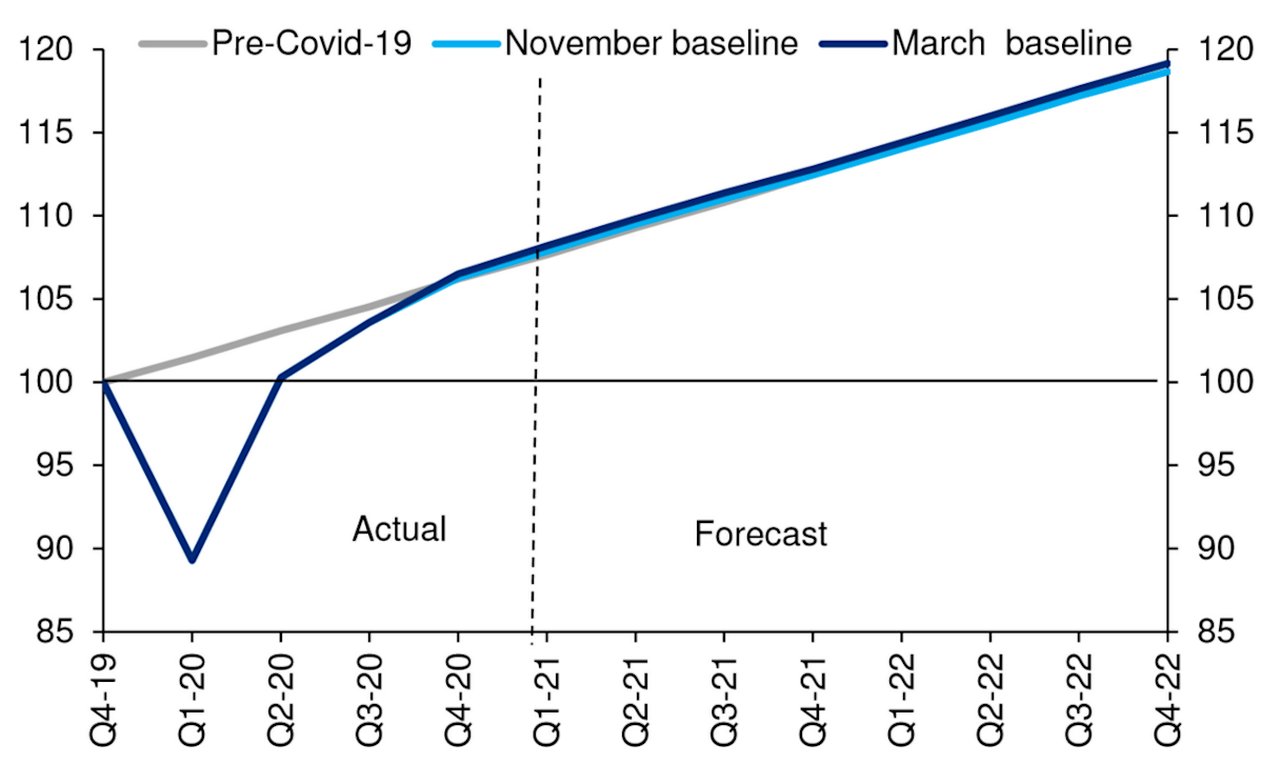

Figure 1: China GDP level projections

Source: Deutsche Bank

The missing growth targets contrast markedly with the shorter-term projections offered by Deutsche Bank Research’s team of Asia analysts in the 16 March publication World Outlook: Goldilocks with Inflation Risk. As per Figure 1 above, they write than China’s economy has already returned to its pre-Covid trajectory and “is likely to overshoot it this year with GDP growth of 10% and an unemployment rate falling back to 2018 levels below 5%”.

China’s consumption has lagged during the recovery, they add as “the government’s stimulus measures were mainly supply-side policies with little support given directly to households”. So the household savings rate rose from 30% at the end of 2019 to 35% in H1 2020, before falling back to 33% in H2. A further decline is expected to see it back at 30% in H2 2021, while household spending is forecast to rise 18% in 2021, with about one-third of that growth coming from the decline in the savings rate.

With the outlook so favourable for growth and unemployment, the team see pandemic-related fiscal and monetary stimulus being gradually withdrawn by the authorities. “We expect the augmented fiscal deficit – on- and off-budget deficits of the central and local governments – to fall from 13.5% of GDP last year (from 8.2% in 2019) to 11% this year and 10% in 2022,” they predict. The Peoples Bank of China (PBOC) is forecast to raise its policy rate (the one-year medium-term lending facility (MLF) rate by 20 basis points (bps) in H2 2020 and “to guide credit growth down gradually – a process that actually began late last year”, while the strong bounce back in growth gives “plenty of scope to tighten policy beyond these relatively modest forecasts”.

Just how strongly 2021 began for China is noted by Yi Xiong in the latest Asia Macro Insight published on 19 March, with China’s trade with the US particularly healthy. “Jan-Feb exports to the US were 87% higher than in 2020 and 36% higher than in 2019,” he reports. “Exports to the EU were also strong at 63% higher than in 2020 and 14% higher than in 2019. Exports to East and Southeast Asian countries were slightly weaker at 51% higher than in 2020 and 12% higher than in 2019”.

Moving away from fossil fuels

It is not just growth targets that have been ditched. Xiong and Feng also comment on the absence of environmental targets, with only five in the 14th FYP against 10 in the 13th. “Only the most crucial targets for achieving China’s climate goals, such as reducing carbon intensity and increasing forest cover ratio, have been kept,” they write. “More detailed targets, such as reducing water consumption and controlling emission of various pollutants, have been dropped”.

The government’s target for reducing carbon emissions over the next five years is by a further 18%, the same as in the 13th FYP, while the energy consumption per GDP unit target is lowered to 13.5% over the next five years against 15% previously, which “likely takes into account the fact that energy intensity was only reduced by 13.7% in 2015-2020”.

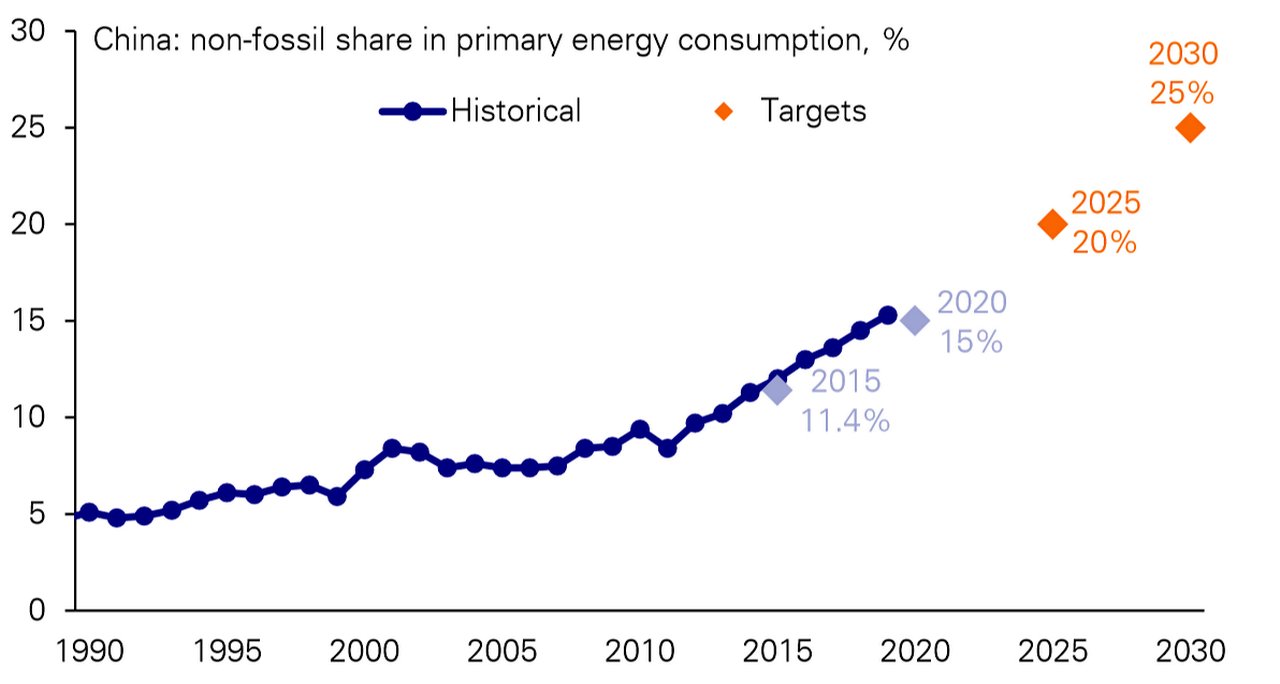

More ambitious is the target for increasing the non-fossil share of China’s energy consumption, which in the 13th FYP was set at 15% for 2020 against 12% in 2015. The government, which recently committed in a climate energy forum to increasing the percentage to 25% by 2030, has also set an interim target for 2025 of 20% as per Figure 2.

Figure 2: China’s non-fossil fuel energy share will increase to 20% by 2025

Source : Deutsche Bank Research, NBS, www.gov.cn

Of the current 15% figure for non-fossil energy consumption, more than two-thirds comes from hydro and nuclear power and while they will remain important, the new target is likely to require a doubling of the contribution from solar and wind power by 2025.

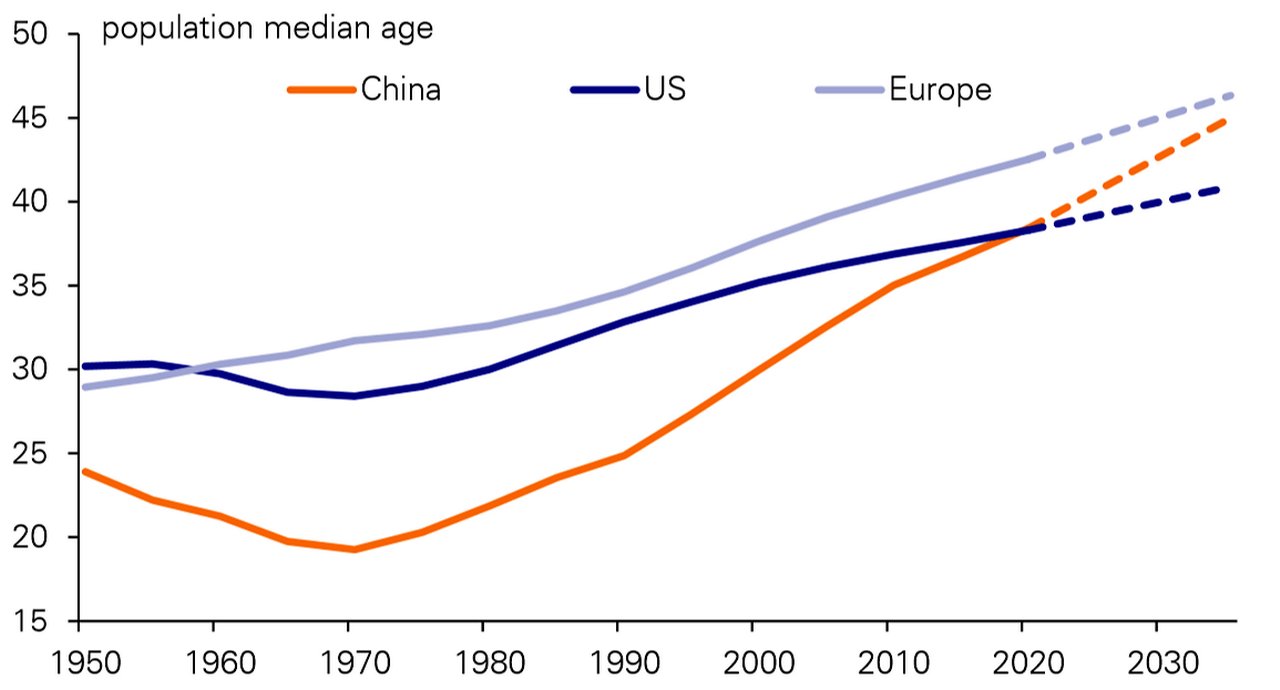

Other areas addressed in the latest FYP is the challenge of China’s demographics and a shrinking labour force. The median age of the population, which stood at 30.8 years in 2000 had increased to 38.4 years by 2020 and is projected to reach 40 by 2025 and 45 by 2035, surpassing the US figure and steadily nearing that of Europe. China’s work age population peaked in 2013 and is decreasing by four to five million each year.

Figure 3: China’s median age had equalled that of the US by 2020

Source : Deutsche Bank Research, UN

Seven ‘livelihood targets’ aim to address the resulting needs and include employment, healthcare, pensions, childcare and education. To increase labour supply, the current retirement ages of 60 for men and 50-55 for women, unchanged for more than four decades, are likely to be raised.

One new target reflects the government’s ambitions of growing China’s digital economy, whose share of the overall economy is set to increase to 10% by 2025 from 7.8% currently. “This implies annual growth of the digital economy sector will be about 5 percentage points higher than the overall economy,” state Xiong and Feng. Total R&D spending, which was previously set as a percentage of GDP terms, is targeted to increase by a minimum of 7% annually and will rise regardless of how fast the economy is growing, The number of high-value patents is also targeted to almost double over the next five years to 12 per 10,000 persons by 2025 from 6.3 currently.

Hong Kong’s future

As The Economist notes in its edition of 20 March China also has plans for the future of Hong Kong, which the paper examines in its briefing titled ‘The way it’s going to be’. Xi Jinping and colleagues still see benefits in preserving Hong Kong as an international financial centre, it suggests. “Operating outside the mainland’s strict capital controls, Hong Kong issues its own currency, the Hong Kong dollar, that is freely convertible against the American dollar, and offers Chinese firms access to some of the deepest pools of capital on Earth”. But its access to Western know-how, as opposed to money “holds less interest for party chiefs”.

The briefing also notes that Chinese officials, state-backed scholars and also pro-government politicians in Hong Kong all contend that neutralising opposition is “a necessary step towards a greater goal: repairing flaws that render Hong Kong’s political and economic systems structurally unsound through a wholesale remodelling of its institutions and society.

“What is more, they are sure that Hong Kong’s role as an international financial centre will generate such profits that Western financial institutions will rush to invest, rendering the grumblings of foreign governments irrelevant”.

A delicate balancing act

As China pivots towards self-reliance with its latest FYP, it remains mindful of global demand and its potential as a hub for direct and indirect investment. It is therefore pushing ahead with ambitious market liberalisation reforms, as the country looks to internationalise the RMB by turning it into the reserve currency of choice for central banks. Greater international usage of the RMB, and providing foreign investors with more confidence in the currency, needs to be balanced with the necessity to maintain or even restrict currency inflows and outflows. As Xiong tells flow: “The regulator needs to preserve a balancing act where international investors are assured that if they have money in China, they can get it out without restrictions. From what I see the PBOC is trying to manage this while gradually increasing exchange rate flexibility.”

Meanwhile, reforms to stock exchange access schemes such Stock Connect, Bond Connect, China Interbank Bond Market (CIBM) Direct have resulted in increased international inflows into Chinese equity and fixed income markets. Offshore investors increased their holdings of Chinese interbank market bonds by nearly 50% in 2020 to top US$500bn for the first time, official Reuters data showed on 7 January 2021.

These market reforms have been instrumental in convincing a number of global benchmark providers such as FTSE Russell and the Bloomberg Barclays Global Aggregate Index to add Chinese debt to their indices. Despite these reforms foreign investor participation in the onshore market continues to be somewhat restrained. Again, this is stifling Chinese efforts to internationalise the RMB. According to International Capital Market Association (ICMA), China’s onshore bond market totals US$15 trillion, making it the second largest in the world after the US, but foreign investors hold just 3% of it.

Opening up capital markets

“Before the QFII and RQFII reforms, it could take from six to nine months for international investors to set up an account. Now the application approval turnaround time has dramatically shortened”

Rules for international investors in China have also been simplified to attract further inflows. In 2020, the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) confirmed that the Renminbi Qualified Foreign Institutional Investor (RQFII) and Qualified Foreign Institutional Investor (QFII) programmes would be merged into one. This announcement came several months after the State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE) abolished the QFII and RQFII investment quotas altogether. Tony Chao, Head of Securities Services, China, Deutsche Bank says the rule changes meant the application process for foreign investors was now more straightforward. “Before the QFII and RQFII reforms, it could take from six to nine months for international investors to set up an account. This was a major hindrance for investors. Now the application approval turnaround time has dramatically shortened, with expanded group of eligible investors able to participate in the scheme”.

Furthering direct investment

In addition, the EU-China agreement on (direct) investment (CAI) signed in December 2020 is another important development suggested that the country is not averse to partnerships. However, reports in the Financial Times2 and other media on 24 March suggested that an escalating sanctions dispute between China and the European Union could see senior politicians in the European Parliament vote down the agreement.

The cumulative EU foreign direct investment (FDI) flows from the EU to China over the last 20 years have reached more than €140bn.3 Xiong describes the agreement as a “breakthrough” in showing that China is moving again (following a period of rebalancing since the Trade Wars) and opening up its market to foreign investors in the form of direct investment. “It’s growing so fast not only as a production and manufacturing hub for countries in the EU but also a financial market. In the last two years authorities have made it easier for foreigners to do business in China and the EU China investment agreement is a milestone in that regard.”

The CAI will ensure EU investors achieve better access to a fast growing 1.4 billion consumer market, and that they compete on a better level playing field in China. The agreement makes conditions for market access cover areas such as manufacturing, the automotive sector and financial services. Joint venture requirements and foreign equity caps have been removed for banking, trading in securities and insurance (including reinsurance), as well as asset management. In relation to improving the level playing, the agreement includes provisions stipulating that Chinese state-owned enterprises should not discriminate in their purchases and sales of goods or services.

Previously market access was restricted to 50% of ownership in some sectors, and this cap has now been lifted. “Many of the service sectors were restricted to foreign investors and we’re seeing the investment deal opening up a lot of these sectors,” observes Xiong.

On the role of state owned enterprises, Xiong notes this is the first time the issue of competition and the subsidies that local companies have received from the government is explicitly addressed by the agreement. “Of course we haven't seen the full article and even if we see it the important question is how they will actually be implemented,” he says. “But knowing that this investment deal will cover many of these issues that we have long heard about from foreign investors as pain points that have been unaddressed, is also very encouraging from that perspective.”

Deutsche Bank Research reports referenced:

Asia Macro Insight: Balancing risks to rates by Juliana Lee, Michael Spencer, Kaushik Das, Yi Xiong and Edwin Kwok (19 March)

China Macro: The 14th Five Year Plan (1): 20 Targets for 2025 by Yi Xiong and Grant Feng (17 March)

World Outlook: Goldilocks with Inflation Risk by David Folkerts-Landau and Peter Hooper (16 March)

Sources

1 See https://go.nature.com/39erQTw at nature.com

2 See https://on.ft.com/3rmMo2u at ft.com

3 See https://bit.ly/3siwKX7 at ec.europa.eu

Go to Corporate Bank EXPLORE MORE

Find out more about products and services

Go to Corporate Bank Go to Corporate BankStay up-to-date with

Sign-up flow newsbites

Choose your preferred banking topics and we will send you updated emails based on your selection

Sign-up Sign-upSubscribe Subscribe to our magazine

flow magazine is published annually and can be read online and delivered to your door in print

You might be interested in

Macro and markets, Regulation, Trade finance and lending

China and the EU: enduring partners China and the EU: enduring partners

As China recovers from 2020 and enters the Year of the Ox, what does 2021 have in store for EU corporates in the country? Upcoming agreements and regulations look set to forge a path for greater investment opportunities

Macro and markets, Cash management, flow case studies

The rise of Global Capability Centres in APAC The rise of Global Capability Centres in APAC

Formerly, it was mainly back-end functions that were outsourced to Asia-Pacific. Today, these hubs drive technological innovation and enhance organisational efficiency on a global scale. What does this mean, both for the treasury function and for corporate banking services?

MACRO AND MARKETS, TECHNOLOGY

China focuses on post-Covid goals China focuses on post-Covid goals

Having warded off the pandemic’s full impact, the world’s second-largest economy can focus on achieving technological self-sufficiency and developing its central bank digital currency, reports flow’s Graham Buck