15 December 2022

In April 2022, Deutsche Bank Research made headlines by reporting that central banks’ battle to rein back inflation at the expense of global growth would precipitate recession in 2023. As 2022 draws to a close, the team reconfirm the economic storm clouds while highlighting their silver linings. flow’s Clarissa Dann reports

MINUTES min read

In early April 2022, just weeks after Russia had launched its so-called “special military operation” in Ukraine, Deutsche Bank made headlines by becoming the first major bank to forecast that the US post-pandemic economic recovery would be a spent force by the end of 2023.

“We no longer see the Fed achieving a soft landing. Instead, we anticipate that a more aggressive tightening of monetary policy will push the economy into a recession,” Deutsche Bank’s team of economists led by Chief US Economist Matthew Luzzetti observed in their report, US Economic Perspectives: US outlook: This time is not different for Fed tightening fallout, published on 5 April.

In their report published the same day, World Outlook 2022–24: Over the Brink, the Bank’s Group Chief Economist, David Folkerts-Landau and Peter Hooper, Global Head of Economic Research, accurately predicted that the Federal Reserve would accelerate its policy of interest rate hikes in an attempt to slow the resurgence in inflation.

Highlighting the spike in energy and commodity prices triggered by the conflict in Ukraine, the report added “it is now clear that price stability…is likely to only be achieved through a restrictive monetary policy stance that meaningfully dents demand”.

As CNN put it at the time, “The good news is Deutsche Bank is not forecasting a deep and painful recession like the past two downturns.”1 Instead, the dip was expected to be relatively mild and confined to Q4 2023 and Q1 2024.

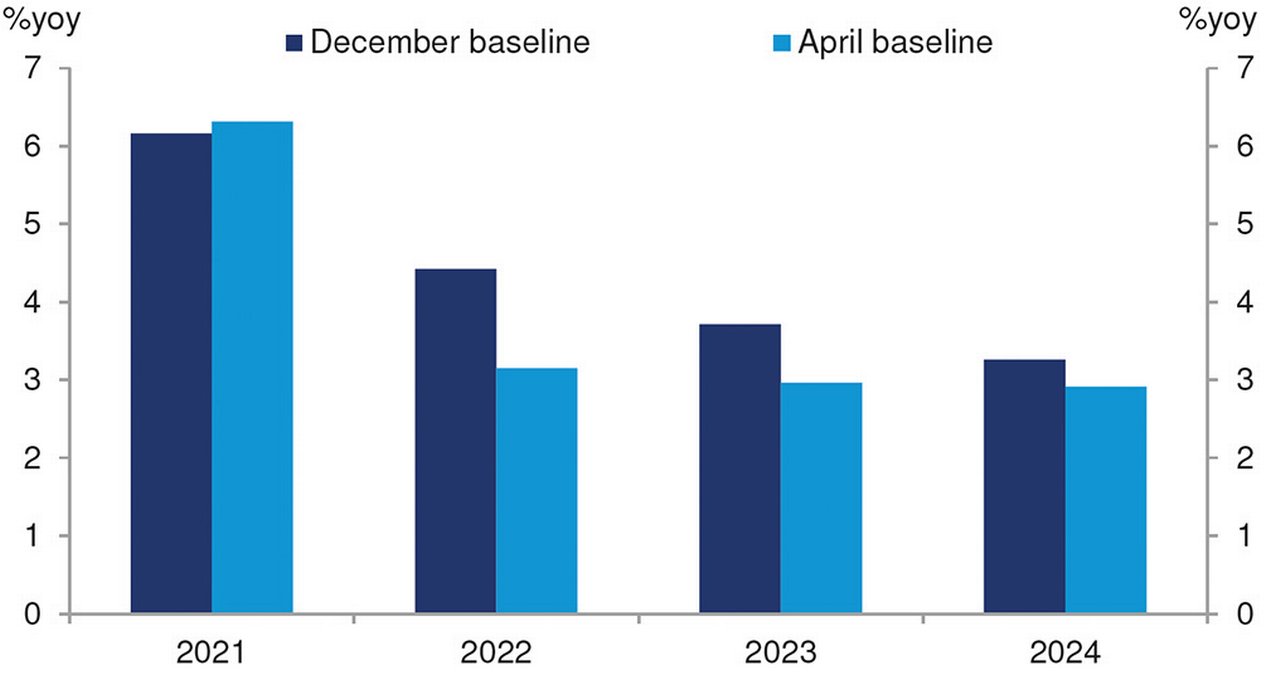

Figure 1: World real GDP growth

Source: Deutsche Bank

Yet before April was out, the bank’s analysts had already revisited – and updated – their initial predictions in a report with the self-explanatory title Why the coming recession will be worse than expected (26 April). It noted how US consumer inflation had spiked to 8.5% the previous month – the fastest rate in 40 years – and getting it back to the Federal Reserve’s target of 2% would be a lengthy process that required interest rate hikes to be accelerated at the expense of growth.

“We regard it…as highly likely that the Fed will have to step on the brakes even more firmly, and a deep recession will be needed to bring inflation to heel,” the Deutsche Bank team concluded.

“2023 will be the third-worst year for global growth so far in the 21st century”

Justified pessimism

In their latest report, World Outlook 2023: The Looming Recession (28 November), Folkerts-Landau and Hooper comment on the “darkening outlook” that supported their pessimistic stance seven months earlier.

“Inflation is running at multi-decade highs, central banks are pursuing their most aggressive tightening cycle in a generation, and a recession is now increasingly expected in the US and Europe,” they observed. “In the meantime, economies and markets continue to be buffeted by a range of other developments, including Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, China’s zero-Covid strategy, and the growing superpower rivalry between the US and China.”

Against this unpromising backdrop, the team believe 2023 is shaping up to be the 21st century’s third-worst year for global growth, exceeded only by 2009 when the fallout from the global financial crisis still prevailed and the pandemic year of 2020 when lockdowns upended economic activity. They now see a US recession beginning by the middle of next year and the Eurozone hampered by stagflation, as member countries “grapple with an energy supply-induced recession and inflation averaging at 7.5%”.

The past year has seen wage and price inflation in both the US and Europe running at rates last experienced four decades ago, fuelled by a combination of robust aggregate demand, very tight labour markets and supply side shocks and constraints.

While the Fed and its central bank counterparts elsewhere in the world have responded with swifter and steeper interest rate hikes than seemed likely at the start of this year, Folkerts-Landau et al point to the historical record for several major industrial countries since the 1960s. This shows that “any time the trend in inflation has declined by two percentage points or more, that decline has been accompanied/induced by a rise in unemployment of at least two percentage points (i.e., at least a moderate recession)”, – and current inflation trends on both sides of the Atlantic are running three to four percentage points above the levels desired by policymakers.

With both the Fed and the European Central Bank “absolutely committed” to taming inflation over the next few years, the price will be “at least moderate economic downturns in the US and Europe, and significant increases in unemployment” even if the severity may be less than in the past. Offering figures, the team predicts a decrease of 1% in the eurozone’s output in 2023 and 1–1.25% in the US, while world growth slows to 2% next year, a rate “that has historically been labelled recessionary.”

The pain is also seen as extending to major stock markets, with a forecast plunge of 25% “from levels somewhat above today's when the US recession hits, but then recovering fully by year-end 2023, assuming the recession lasts only several quarters”.

Better now than later

There is, potentially, a silver lining among these various dark clouds. The team expect the Fed and the ECB’s mission to rein in inflation to ultimately succeed, although they will need to “stick to their guns” to do so in the face of “withering public opposition” as unemployment levels mount. But the cost is seen as relatively moderate compared against the price of failing to act now and creating “a more severely ingrained inflation problem down the road”.

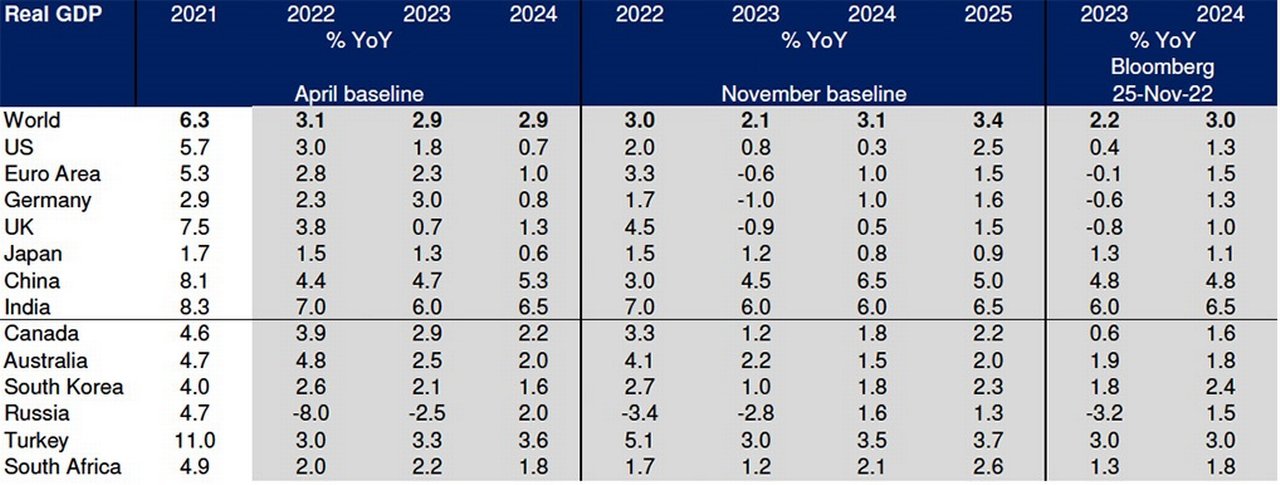

Figure 2: Deutsche Bank growth projection weaker than both its April 2022 forecast and current Bloomberg Consensus

Source: Bloomberg Finance LP, Deutsche Bank

The main prize will be a more sustainable economic and financial recovery that gets underway in 2024, although Folkerts-Landau and team downplay expectations and predict a more moderate rally than the “strong bounces” seen after past recessions. Factors likely to continue to weigh on global growth in the near term include “uncertainties relating to both the Russia-Ukraine conflict—including a lingering energy-induced competitiveness shock in Europe—and the growing US-China strategic competition.”

There are also the near-term implications of how China's zero-Covid policy is likely to play out, although recent days has provided regular evidence that this is being abandoned faster and more widely than had previously seemed likely.

Lest the report be regarded as all doom and gloom, the Deutsche Bank team offer several reasons to suggest that while unemployment is set to rise again, the other costs of taming inflation may be less this time around than previously. They include the following:

- Central banks have learned from historical experience: The Fed and the ECB were slow to recognise the severity of the inflation problem, but when eventually they did, both moved aggressively to deal with it, raising rates faster than at any time since the Volcker era of the 1970s/early 1980s. This has helped cap longer-term inflation expectations and will contribute to inflation moving lower as aggregate demand softens.

- Structural changes in labour markets: These have improved prospects for disinflation. Elevated inflation is less ingrained in the economy than throughout the 1970s because wage-price dynamics have eased. Labour unions are now much less prevalent or potent than several decades ago and their reduced bargaining power means that the near automatic indexation of wages to increases in prices is much reduced.

- The relative brevity of the current inflation episode: This has meant that memories of the prolonged era of low inflation are still fresh, while high inflation has had less opportunity to work its way into the system as sustainably as it did throughout the 1970s.

Yet offsetting these are some caveats. The return of inflation is recent but has broadened significantly. “Inflation is now much more than a supply-driven goods sector problem. It has spread deep into service sectors and now excessively tight labour markets,” the report notes. Add to this the fact that the Phillips curve – the economic theory that inflation and unemployment have a stable and inverse relationship – has flattened since the 1970s, requiring central banks to work harder and raise unemployment more to reduce inflation.

Ultimately there are “good reasons to expect the costs of dealing with the current inflation will be lower than in the past, but also good reasons to expect they will still be significant,” the authors conclude.

Deutsche Bank Research reports referenced:

US Economic Perspectives: US outlook: This time is not different for Fed tightening fallout, by Matt Luzzetti, Brett Ryan, Justin Weidner and Amy Yang (5 April)

World Outlook 2022–24: Over the Brink, by David Folkerts-Landau and Peter Hooper (5 April)

Why the coming recession will be worse than expected, by David Folkerts-Landau, Peter Hooper and Jim Reid (26 April)

World Outlook 2023: The Looming Recession by David Folkerts-Landau and Peter Hooper (28 November)

Corporate Bank solutions Explore more

Find out more about our Corporate Bank solutions

solutions

Stay up-to-date with

Sign-up flow newsbites

Choose your preferred banking topics and we will send you updated emails based on your selection

Sign-up Sign-upYou might be interested in

CASH MANAGEMENT

Investing strategies in inflationary times Investing strategies in inflationary times

In an Economist Impact webinar supported by Deutsche Bank, two corporate treasurers shared how inflationary pressures are affecting their investment strategies – and why the Covid-19 pandemic is still shaping cash policies. flow summarises the three key learning points

TRADE FINANCE, MACRO AND MARKETS

Trade and inflation: the five basic issues Trade and inflation: the five basic issues

As the world grapples with cost of living and energy security crises, inflation continues its relentless rise. Dr Rebecca Harding considers five questions around the links between inflation and trade, finding the answers in trade flow data

MACRO AND MARKETS

US economy: timing is all US economy: timing is all

Federal Reserve chair Jerome Powell plans to start tapering off its asset purchase policy as the US economy recovers. But to what extent is the Delta variant of Covid-19 undermining this strategy? flow’s Graham Buck reports