20 May 2020

As economies move along their pandemic exit trajectories, and the cost of economic stimulus raises the spectre of galloping inflation, flow's Clarissa Dann reviews Deutsche Bank Research analysis on whether this scenario is likely given the current central bank grip on markets

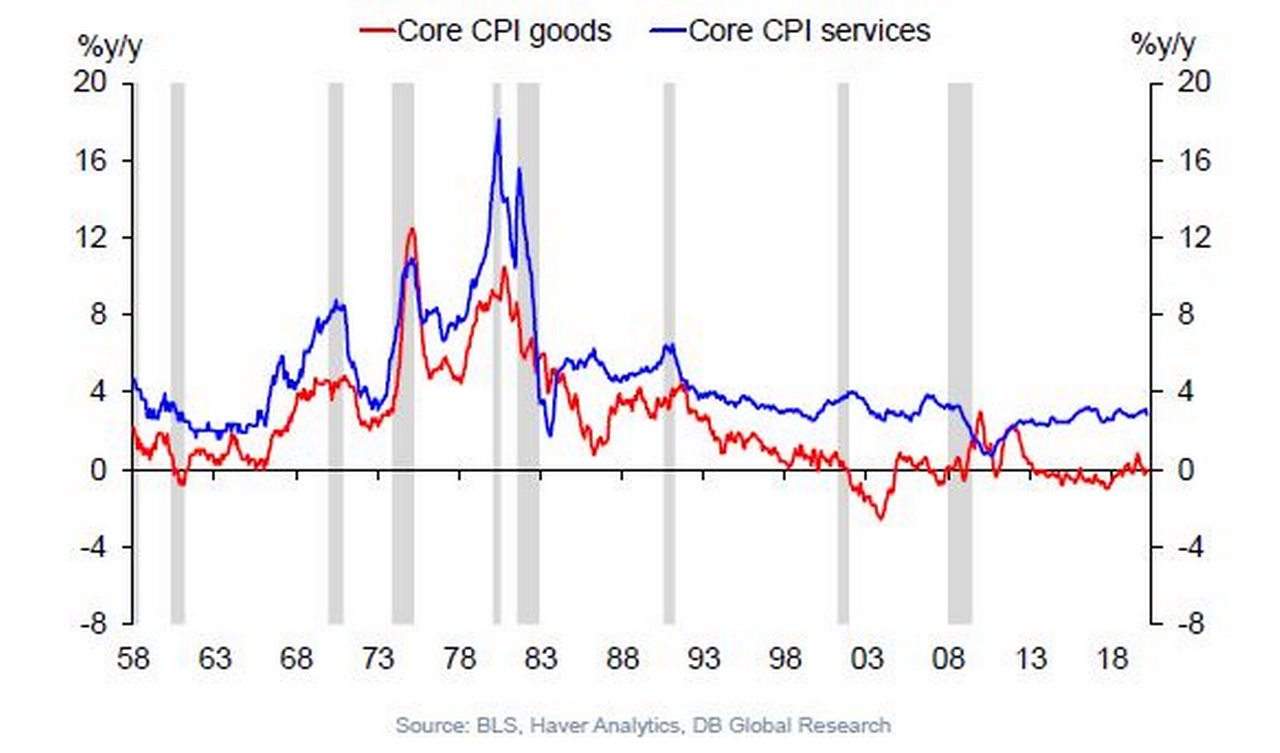

After 30 years of low inflation, this benign era could end abruptly once lockdowns are lifted and economic activity picks up after the Covid-19 shock (see Figure 1).

While the types of hyperinflation seen in Venezuela (2019), Zimbabwe (2007) and Germany in the 1920s (1923 million mark bills remain a collector’s item today along with photos of when wages were carried away in wheelbarrows) does not look set to reappear in G20 economies anytime soon, they remain warnings of what happens in extremis.

However, price rises of more than 10% a year that can destabilise economies and deter foreign investment remain a potential threat in a number of Covid-19-struck economies and are worrying analysts. Deflation, triggered when prices fall (as they have done with oil) creates another set of problems – a rise in the household debt burden where consumers have borrowed in the past and reduced their spending.

One and two million mark banknotes from the Weimar Republic, Germany in 1923, illustrating hyperinflation

Figure 1: US: Basically no goods inflation since the mid-1990s

Pandemics have, in the past, led to an increase in precautionary savings. As individuals worry about what might be around the corner, they don’t spend. And this situation, notes Deutsche Bank Wealth Management’s CIO insights: Through difficult waters, “can last for a long time”.1 The report points out how Japan is an example of how “high savings can coexist with high levels of government debt for many years, with default not the issue (due to low or negative real rates, and a private sector that is conditioned to buy government bonds), but with a damaging impact on growth”.

While inflation has been the convenient way out of these difficulties in the past, demand-pull inflation, adds the report, “seems unlikely in the current situation as increases in government spending (already high) are unlikely to fully offset the fall in overall demand.” It adds that “supply-driven inflation is possible in some areas – as changes to supply chains, repatriation of production and reassessment of globalisation in general pushes up costs – but seems unlikely to be able to offset the overall depressing effect on prices from contracting or significantly slower growth in demand in the medium term.”

So, will Covid-19 bring about inflation, deflation or a bit of both?

Bail-out blues

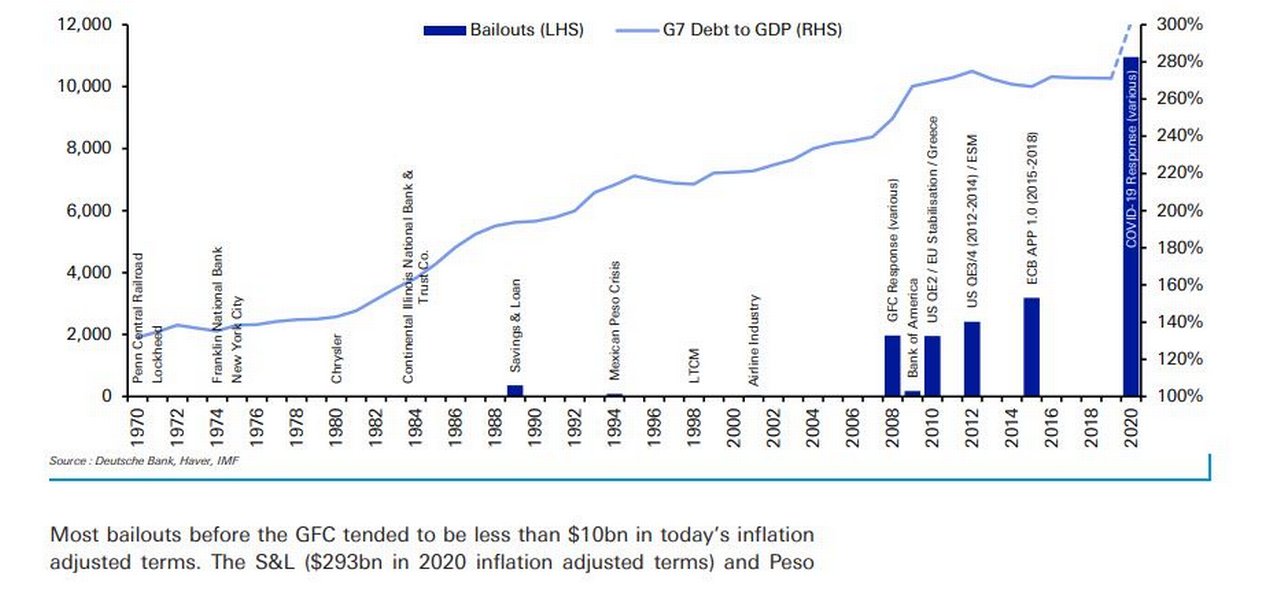

Figure 2: Biggest bailouts in history in 2020 USD (US$bn) vs. G7 debt to GDP

One of the compelling arguments for inevitable inflation is the sheer scale of the 2020 government bailout packages and their long-term economic impact. This was something we touched on in Towards a silver lining (3 April) with a graph of the global debt mountain and the comment that “the massive fiscal packages… will have to be paid for eventually one way or another”

In 2010 Deutsche Bank published a chart looking at the biggest bailouts up to the Global Financial Crisis and commented at the time at how the GFC was inflating the rescue currency relative to history. In the light of the size of the bailouts seen as a result of Covid-19, the Thematic Research team recently updated this in their 20 April report, The biggest bailouts in history.

Figure 2 shows large bailouts/interventions, covering both government and central bank moves, seen each year since 1970 in US inflation adjusted terms. At the end they have shown the graph on a log scale so as to better identify the earlier bailouts and get a handle on their magnitude. For 2020 the team aggregated the fiscal and monetary support programmes announced from the US and the largest economies in Europe. “Obviously we won't know how much will be used until much further down the road but these are the main commitments undertaken so far as we see them,” they explain. “We’ve also added G7 overall debt (private and public) to GDP to the charts to show that as debt gets higher so does the level of bailouts/intervention needed to protect the system. We have made a rough approximation for G7 debt/GDP for 2020.”

“Most bailouts before the GFC tended to be less than US$10bn in today’s inflation adjusted terms. The [1986-95] savings and loan (S&L) crisis (US$293bn in 2020 inflation adjusted terms) and [1994] Peso (US$93bn) crises saw higher numbers but still relatively small for more recent times. The GFC moved us from ten billion being a big number to a trillion being the new bail-out currency. This Covid-19 crisis has moved us towards ten trillion plus being the bailout currency globally.”

Return of inflation

Deutsche Bank Macro Strategist Oliver Harvey predicts that the combination of unprecedented government stimulus packages, retreating globalisation, the increase in bargaining power of certain sectors of the labour market as well as the need to reduce large debt burdens will bring about the return of inflation.

In his Konzept article, The case for inflation (page 18) he makes the point that while European government attempts to keep household incomes stable with job retention schemes , although they “have the best of intentions”, will simply result in “more money chasing after significantly fewer goods and services”. To put it bluntly, he adds, “The government is handing out US$100 bills when there is nowhere open to spend them”.

The Economist (18 April) concurs: “Worries about soaring prices start with the observation that virus-fighting measures choke off production. Crudely put, inflation is the result of too much money chasing too few goods. At present the amount of goods and services available for purchase is tumbling. Many service industries are shut down. The virus is playing havoc with the supply of some products.”2

The other problem is that a number of industries will be less profitable once some form of ongoing social distancing regulation limits the capacity at which they are allowed to operate. Examples are restaurants and airlines – which given the low-margin nature of their business models – means they rely respectively on high volumes of table bookings and flight turnarounds to be profitable – therefore the prices charged by such entities still in business would most probably rise. “If you assume 80% of restaurants cannot supply at, say, 60% capacity, do you think the price of a restaurant meal will go up or down?” asked Harvey on a recent Podzept podcast.3

As for all those precautionary savings, households’ spending and saving behaviour is – as every economist knows, says Harvey – “about expectations”. He predicts “as soon as households perceive the price of everyday goods and services starting to rise, their rainy day funds will quickly be raided to buy them.”

Another indicator that inflation is on its way back is, he adds, deglobalisation. The effects of globalisation on suppressing inflation were:

- Cross-border immigration and the offshoring of production increased the global labour supply, putting downward pressure on workers’ wages, particularly among the lower-skilled

- Enhanced competition in the manufacturing sector led to a decline in the cost of many consumer products.

The perception that high inflation is just around the corner is out there – a Deutsche Bank Data Innovation group (dbDIG) survey found that a majority of the Bank’s clients expect the pandemic to be ultimately inflationary. However, the drop in aggregate demand, says Torsten Sløk, Chief Economist, Deutsche Bank Securities, suggests that “we will not see inflation anytime soon”.

While this might be a comfort for some investors, what is the prospect of deflation, Japan-style?

"The government is handing out US$100 bills when there is nowhere open to spend them"

Case for deflation

The short answer is that it depends on one’s perspective.

In its Economic Letter (May 2020), the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco examines the risk of “a significant drop in inflation from its current level” and assesses the odds using yield curve models of nominal and real government bond yields from: Canada, France, Japan, and the United States.

Its analysts conclude: “Analysis of the forward-looking information in nominal and real government bond yields shows that the perceived risk of an outright decline in the price level, or deflation, over the next 12 months has barely changed in the four countries we examine.

“Furthermore, the premium investors attach to deflationary outcomes has seen at most only a modest uptick, except for in Japan, where this premium was already elevated thanks to its near-zero inflation. Overall, these results suggest that the perceived risks of a substantial decline in inflation are limited in the near term despite the economic standstill caused by the coronavirus.”4

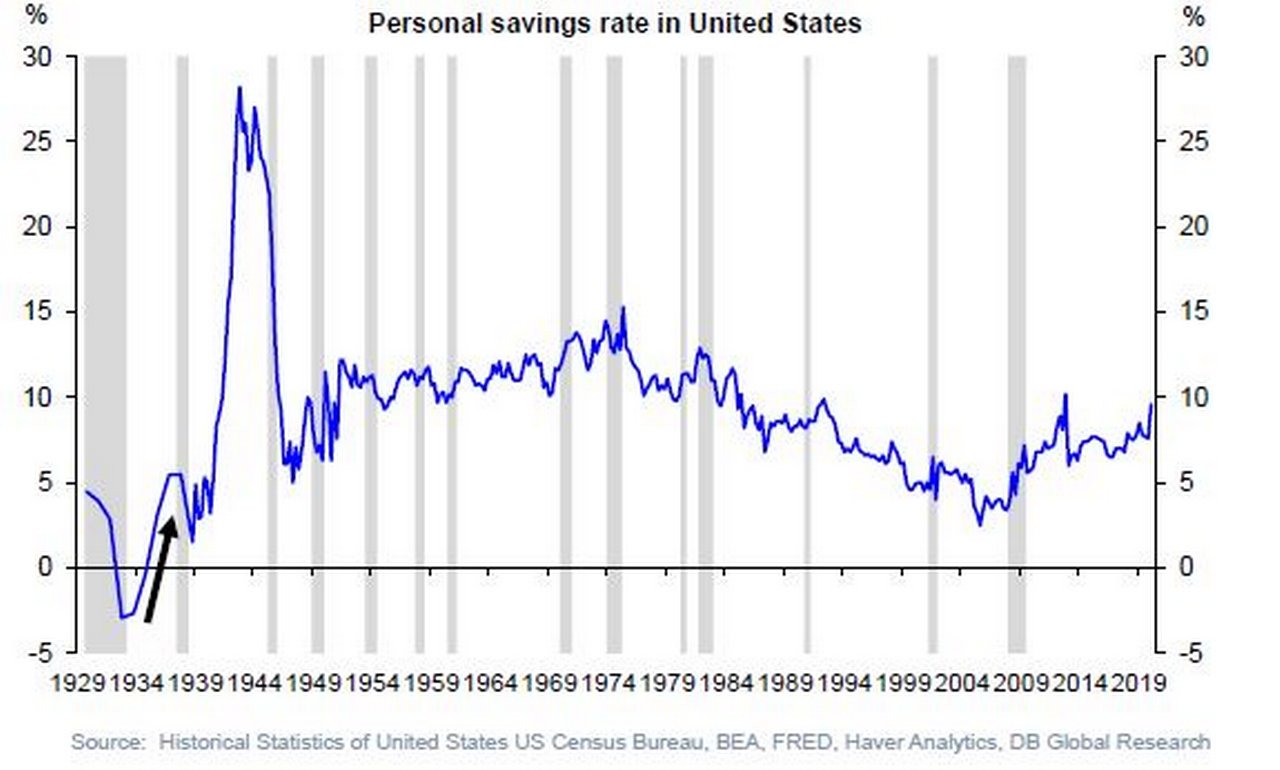

During his discussion with Oliver Harvey on the Podzept podcast, Deutsche Bank FX Strategist Robin Winkler says that “it all boils down to how quickly demand bounces back once we come out of this crisis and I am not optimistic.” He explains that what academics have learned from pandemics over the past 800 years is that people put a premium on having a “rainy day fund” after the event – something that is being underlined by current consumer surveys.5 See Figure 3.

Figure 3: Personal savings rate in the United States

It is not just that right now consumers don’t have anywhere to spend their money – households are making conscious choices to save more. “This is not surprising” says Winkler and points to the Covid-19-related record high unemployment level, business bankruptcies and overall sense of uncertainty. “All of this will make households more precautionary for years to come and we will end up with a chronic demand deficiency that will take a long time to be washed out,” he reflects.

But what about the ten trillion in bailouts from government stimulus packages? In their Konzept article, The case for deflation, Robin Winkler and fellow FX Strategist George Saravelos point out that that “a big chunk of the fiscal measures announced are loan guarantees rather than fresh new money”.

Furthermore, they maintain, “There is nothing stimulative [sic] about adding more debt to corporate balance sheets. But even the direct stimulus is designed to be temporary and self-calibrating. Consider the employment protection schemes in Europe, whose size is purely a function of the unemployment rate and will disappear once employment goes back to normal. The bulk of the US fiscal stimulus is also temporary – households have received a one-off pay cheque, more likely to be saved rather than spent, like in 2008. As things stand, the fiscal stance is set to be massively contractionary next year, not expansionary.”

In flow’s 17 April article, Central banks: onside or outside? Saravelos reflects on the demise of free markets and central bank clout. When it comes to managing inflation post-Covid-19, the controls are all in place. “On the monetary side, central banks have not given up on their commitment to inflation targets and their independence does not seem jeopardised… There is little reason to think that central banks could not turn around policy stance on a dime if inflation reared its head,” note Winkler and Saravelos in their Konzept article.

Nor, they add, would governments and central banks be any more tolerant of overshot inflation now than they have been during the past 40 years. “The world has lived with disinflation for centuries. We should worry about turning into Japan, not Zimbabwe,” they conclude.

"We will end up with a chronic demand deficiency that will take a long time to be washed out"

Creative destruction

Although this article has concentrated on inflation and deflation scenarios, other drivers – also discussed in Konzept – will shape the world’s climb out of Covid-19. These include what happens to global value chains now, as The Economist puts it on 14 May (Has Covid-19 killed globalisation?) “Governments and central banks are asking taxpayers to underwrite huge national firms through their stimulus packages” and “the push to bring supply chains back home in the name of resilience is accelerating”.

Covid-19 has launched an economic shock the like of which the world has never seen before – but the world is also better equipped to deal with it, note analysts. In his introduction to Konzept, Deutsche Bank’s Global Head of Fundamental Credit, Strategy and Thematic Research Jim Reid asks whether the monetary and fiscal intervention to make debt sustainable “creates a medium-term dilemma about whether it stifles creative destruction”.

The analysts comment that although “this is a trend that will continue”, there are forces at work that will still allow creative destruction to happen “without resorting to the economic malaise that sometimes accompanies it”.

In other words, the new normal will be somewhere between the extremes of Zimbabwe (galloping inflation) or Japan (deflation). It just depends on which balm economies apply to the pandemic scar tissue as to where on the spectrum between the two extremes that might be.

Summary of Deutsche Bank reports referenced

- The biggest bailouts in history, 20 April 2020, by Jim Reid, Nick Burns and Craig Nicol

- Konzept # 18: Life after covid-19 (pages 18 to 23, 14 May 2020) Deutsche Bank Thematic Research

- Global Macro Outlook: Slow recovery ahead (19 May 2020) by Torsten Sløk,

- Podzept: Is Covid-19 Inflationary or deflationary (13 May 2020) with Jim Reid (Moderator), Oliver Harvey and Robin Winkler

Sources

1 See https://bit.ly/2Zne5hs at deutschewealth.com

2 See https://econ.st/2LLR0Nb at economist.com

3 See https://bit.ly/3cNLgyD at dbresearch.com

4 See https://bit.ly/36dXw92 at frbsf.org

5See https://bit.ly/3bNRT2n at frbsf.org

Go to Corporate Bank EXPLORE MORE

Find out more about products and services

Go to Corporate Bank Go to Corporate BankStay up-to-date with

Sign-up flow newsbites

Choose your preferred banking topics and we will send you updated emails based on your selection

Sign-up Sign-upYou might be interested in

MACRO AND MARKETS

Central banks: on-side or outside? Central banks: on-side or outside?

How much “support” should central banks give Covid-19 stricken economies? With the focus on fiscal responses, what tools remain in the monetary policy armoury? flow´s Clarissa Dann reviews Deutsche Bank Research insights

MACRO AND MARKETS

Jobs and Covid-19 Jobs and Covid-19

As lockdown continues into Q2, unemployment escalates in all regions. What does this mean for economic recovery? Clarissa Dann reports on the balance between profit and GDP tomorrow versus survival today

Technology, Macro and markets

AI deep research – is this a gamechanger? AI deep research – is this a gamechanger?

The flurry of AI deep research launched at the beginning of 2025 has significant consequences for knowledge workers – and the global economy. flow shares insights from Deutsche Bank Research’s paper that identifies winners and losers – and AI’s capacity for longer-term self-improvement