10 May 2023

Angola was once top coffee producer and could feed its people but is now dependent on hydrocarbon exports to finance foodstuff imports. flow’s Clarissa Dann reports on how enlightened government reforms are attracting investment and lending to support long-term energy and food security

MINUTES min read

Bordering Botswana, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Namibia, and Zambia, Angola sits at the heart of southern Africa, and just across the Atlantic from its fellow Lusophone Brazil. With a central plateau, high plains, mountains and hills, and narrow coastal plains, the Congo River and a vast network of waterways pass through its varied landscape turns into a huge wetland, emptying out at various points along its lengthy coastline.

The river systems, most of which have their sources in the highlands of Bie-Huambo, of South Angola were of strategic importance to the former Portuguese colony not only in terms of risk management and flood prevention, but as opportunities to build dams for irrigation during dry seasons and harness hydro-electric power. By the late 1950s, the Portuguese government had become used to the steady revenues flowing from the diamond, coffee and petroleum exports and its river system management was just one example of pre-independence infrastructure that maximised the potential of its natural resources, water being one of its most important assets.

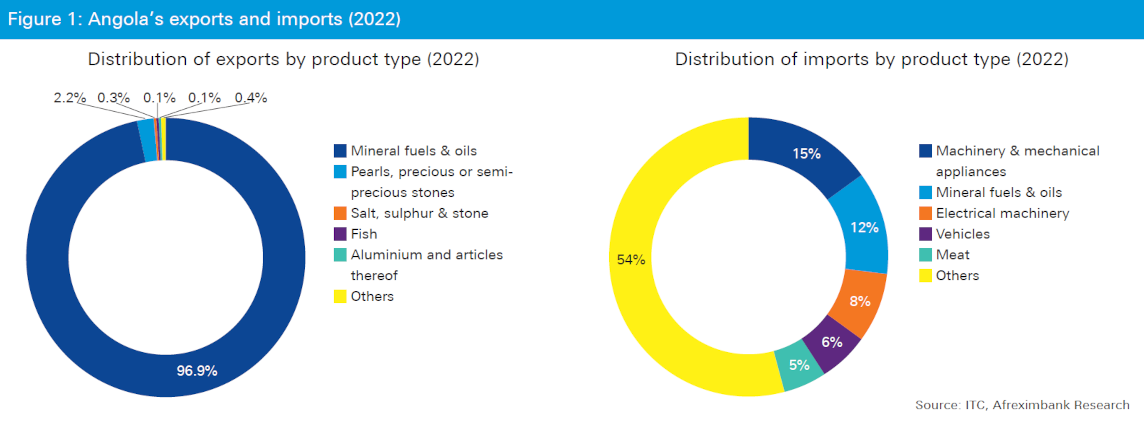

Thanks to its rich soils and reliable rainfalls Angola was once almost self-sufficient in terms of food security (apart from wheat) and a significant agricultural and minerals exporter. The discovery of the petroleum reserves off the coast of Cabinda in 1955 fuelled an economic boom, but the current state of oil dependency to the tune of 97% of exports (diamonds being another 2%) only came about once the Portuguese had left – the civil war that raged until 2002 had done its damage, plantations were destroyed, flour milling capacity extinguished, and agricultural experts such as coffee agronomists took their skills to Brazil, never to return.

By 1976, just after the end of the war for independence, 408 of the country’s 692 factories had closed, 2,500 businesses had ceased trading (75% of which were abandoned by their owners), more than 30,000 managers, technicians and skilled workers had fled, and 145,000 of the country’s 153,000 registered vehicles had been destroyed, along with countless bridges and roads.1 After the end of the civil war in 2002, a million had died and four million had been displaced, 30% of Angolan children died before the age of five, and 60% of Angolans lacked potable water.2

Since those dark times, Angola has rapidly become one of the fastest growing economies in the world and its young upwardly mobile population of around 34 million (the median age is 16) puts it in pole position to continue this growth acceleration. Its status as an oil exporter has supported an appreciation of the national currency ((kwanzas), helping to curb import inflationary pressure. However, annual inflation remains stubbornly high (more than 20%) with food prices the main contributing factor.3 In short – Angola is at an inflection point with food and energy security within its grasp.

“Angola is the only country in Sub-Sahara Africa that did really well in trying remove restrictions and implementing major reforms”

Enlightened reforms

Jose Eduardo dos Santos had served as President from 1979 until 2017; while the transition to his fellow MPLA4 successor João Lourenço went smoothly, it coincided with the slump crude prices that persisted throughout much of Lourenço’s first term of office. The fiscal pain was exacerbated the increased spending and reduced receipts as during the Covid-19 pandemic. A lengthy recession followed together with a quintupling of the country’s debt service costs, a debt restructuring with Chinese lenders, and an IMF bail-out loan. This was an unwelcome distraction to the government committed to find efficiencies in public spending and to diversify its economy.

But Angola bounced back from this: crude prices and FDI are on the up, and João Lourenço was re-elected in August 2022 with a small majority. The most rapid progress has been made in the past few years, reflects Andreas Voss, Deutsche Bank’s Chief Country Officer for Nigeria and Head of Trade Finance for Financial Institutions across Sub-Saharan Africa. He points out that the bank had exited the country in 2015, removing USD clearance when it was hit by sanctions and a dollar shortage resulting in restrictions in dollar access. “If you wanted to make a trade, you had to put dollars with the Central Bank,” he recalls.

Transforming the state-led and oil-funded economic model into a sustainable, inclusive, private-sector-led growth model requires high-level political commitment, strong coordination and communication capacity, and solid institutions, explains the World Bank. “While much remains to be done to achieve this transformation, the Angolan government has taken important steps to safeguard macroeconomic stability and delivered on several key reforms. This includes a more flexible exchange rate regime, active debt management, the Law on Preventing and Combating Money Laundering, the Fiscal Responsibility Law, and the Privatization Law,” it stated in 2022.5

“I think the Angola is the only country in Sub-Sahara Africa that did really well in trying remove restrictions and implementing major reforms,” continues Voss. This is attracting investment and lending – for example the EU and Angola agreed their first sustainable investment facility in November 2022.6 Another important reform was a softening of local content and partnership requirements for foreign investors.7

Angola’s successful implementation of the IMF programme in January 2022 earned congratulations from the IMF Executive Board, which commented on 6 March 2023, “Directors encouraged the authorities to maintain the reform momentum and diversify the economy to safeguard the hard-won macroeconomic stability and to ensure an inclusive and sustainable growth.”8

“Putting in the infrastructure will motivate the banks to give loans to the private sector”

Vera Daves de Souza, Minister of Finance (and one of only a handful of female finance ministers in Africa), is committed to making the private sector the main driver of economic growth, have already announced plans to sell shares in Sonangol and 194 other state-owned enterprises. She wants the country to be less dependent on oil revenue– and in a better position to be part of the solution to the climate change problem. “We need to put our effort into the real economy”, she told The Banker in an interview in October 2022.9 “Putting in the infrastructure will motivate the banks to give loans to the private sector,” she added. The National Development Plan 2023–2027 addresses how the country plans to reduce oil revenue dependency to no more than 20%.10

“The government has made some hard decisions but that the reforms will in the long-term have a very positive impact and it has done a fantastic job. Banks are encouraged by the government’s support for investment and improved value chains,” says Deutsche Bank’s Voss, who confirms Deutsche Bank has clean lines to Angolan banks to support investment in agriculture, food processing among other transactions.

However, the balance between driving through unpopular fiscal measures and managing civil unrest is a difficult one. “There is an elevated threat of widespread political and socio-economic unrest in the coming year, particularly in light of an imminent gradual phasing out of fuel price subsidies,” noted Pangea Risk on 31 March.11

Figure 1: Angola’s exports and imports (2022)

Source: ITC, Afreximbank Research12

Hydrocarbons and minerals

Energy

Although oil was discovered in Angola in the 1700s, oil was first drilled in 1915, and first commercially produced (at the Benfica oil field) in 1955–56.13 The sector continued to function through both the war for independence and the civil war. By 2021, mineral fuels and oils comprised around 94% of Angola’s export earnings, with precious/semi-precious stones accounting for an additional 4.6% (see Figure 1).

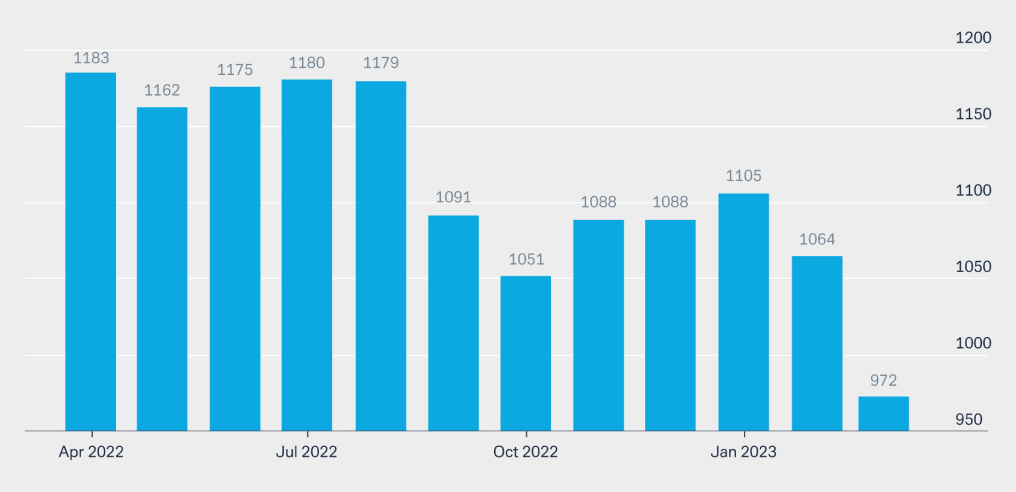

Angola’s offshore oil was first discovered in 1968,14 and much of the country’s known oil reserves are located far offshore and deep (or even ‘ultra-deep’), which results in relatively high production costs. When the oil price falls to around US$50/bbl, Angola’s oil sector becomes comparatively less attractive than other hotspots. Now that oil prices are higher FDI has flowed back in. Angola is Africa’s second biggest oil producer, and it holds Africa’s second greatest reserves of oil too. These are estimated at almost nine billion barrels of proven crude oil reserves and 1.6 trillion cubic feet of proven natural gas reserves.15 However, production has declined in recent years because of the rapid depletion of mature reservoirs and a reduction in investment. However, the rise in oil prices has, notes Pangea risk, “accelerated the pace of new investments in Angola’s oil and gas sector over the past few months” (see Figure 2).16

Figure 2: Angola’s crude oil production (000 barrels a day)

Source: Trading Economics (4 May 2023)

“A lot of investment is pouring in from the oil majors” observes Danai Koutra, Head of Natural Resources Finance UK at Deutsche Bank. But the investment – and the bank lending – is doing more than merely getting hydrocarbons out of the ocean floor. It supports the Angolan government in its ESG objectives as well as its energy security. One example of this is the Azule Energy seven-year US$2.5bn pre-export financing signed in August 2022.

The company was formed as a 50/50 joint venture (JV) between the Angolan operations of oil industry leaders BP and ENI, making it Angola’s largest independent equity producer of oil and gas, holding two billion barrels equivalent of net resources and growing to about 250,000 barrels equivalent a day (boe/d) of equity oil and gas production over the next five years. It holds stakes in 16 licences (of which 6 are exploration blocks) and a participation in Angola LNG JV. Azule Energy also took over Eni’s share in Solenova, a solar company jointly held with Sonangol, and the collaboration in the Luanda Refinery.17

Koutra explains, “the oil and gas industry has the appropriate skillset to help us all move towards net-zero…with opportunities for investment and further employment”.18 Angola already draws more than half its energy from hydroelectric power thanks to its vast waterway network, and is well placed to harness its on and offshore wind resources. “Angola is looking towards other continents such as Europe, which is home to a plethora of companies with extensive expertise in successfully executing wind energy projects and can serve as ideal partners,” noted Energy, Capital and Power in 2022.19

Diamonds and other minerals

Quite apart from their value as gemstones, diamonds are a key component in industrial cutting tools and will be found in electronic appliances and medical instruments. The sub-soil riches of Angola can also be seen in its world-class diamond sector. As the world’s fourth largest producer of rough diamonds, Angola has a 12% share of the global market.20 Endiama had been both the sector regulator and the state-run diamond company, holding exclusive concessionary mining rights regarding diamonds. Although there had already been much private sector FDI in this area, FDI prospects were enhanced when, in 2020, a mining national concessionaire entity (Agência Nacional de Recursos Minerais or ANRM) was created, reducing the role of Endiama in the sector.21 In 2022, Endiama produced 8.75 million carats.22 Under its current growth plans, Angola should be the world’s second largest producer of rough diamonds by 2030. The country is well on its way – thanks to new discoveries of diamond deposits, Angola can claim to be the only country in the world where diamond production has actually increased in recent years.23

In addition, Angola has sizeable reserves of critical minerals such as copper, gold, iron ore and platinum and holds commercially significant reserves of marble, ornamental stones, and quartz, and of phosphates.

Agriculture and food production

Just before independence from Portugal in 1974, Angola was one of the largest coffee producers in the world, and an important producer of palm oil, bananas, sisal and sugar cane. Its agri-businesses were key export earners, were diversified so there was a balance of cash crops and domestic foodstuffs. As rainfall increases from south to north, the produce would vary. Cattle were reared in the drier south, maize was cultivated in the central highlands, and the climate of the north favoured not only coffee, but also cassava and cotton.24 While war for independence and civil war took out the entire infrastructure from farm to fork (Angola now imports half of its food) its natural resources endure and revitalisation of this former land of plenty is a key government priority.

Angola has a potential 35 million hectares of arable land, but at present only around 10% of this is cultivated. And of this 10%, only around 10% is commercially farmed – the bulk of farms being small and largely devoted to subsistence or communal farming.25 With agriculture comprising only around 10% of Angola’s GDP (although employing – formally and informally – 46% of the population),26 the scope for further investment and lending to add value here is significant.

Banco de Desenvolvimento de Angola (BDA) is a public financial institution created with the aim of supporting Angola’s sustained economic growth. Deutsche Bank acted as sole arranger, agent and lender on the €56.9m export agency- covered financing (SACE) to support a private sector project in Angola.27 The transaction, which closed in April 2023, falls under the Framework Export Credit Agreement (ECA) with the BDA and Angola’s Ministry of Finance signed in May 2019 between Deutsche Bank, BDA and the Angola’s Ministry of Finance to fund private investment projects in the country.

The funds are financing a new turnkey food processing plant promoted by Angola-based food production company, Carrinho Empreendimentos LDA. The supply and construction of the new plant will be provided by Andreotti Impianti S.p.A. (Italy) – an Italian engineering company that is active in the design, manufacture, erection and start-up of plants for the production of edible oils and fats.

Located in Lobito, the plant will be the largest of its kind in Africa, with throughput capacity of up to 4,000 tons of soybeans or 2,400 tons of sunflower seeds per day. Construction of the soybean and sunflower crushing plant is expected to take around two years and create approximately 300 direct jobs and thousands of indirect jobs related to soybean and sunflower planting.

“This production facility supports the local economic transition from reliance on commodities production, to creating higher value-add food processing, thereby reducing food imports and enabling local economic activity to rise up the value-chain,” says Werner Schmidt, Deutsche Bank’s Head of Structured Trade Export Finance.

Patrícia D’Almeida, BDA chief executive, adds the plant will be “a valuable contribution to Angola’s ongoing process of economic diversification”.

Outlook

In short, this resilient and rebounding country presents huge opportunities for investment and lending. The government has had to make tough decisions impacting its popularity, but these are shaping up into a long-term positive trajectory for Angola’s economy.

Sources

1 See tile.loc.gov

2 See france24.com

3 See fao.org

4 See Movimento Popular de Libertação de Angola

5 See worldbank.org

6 See ec.europa.eu

7 See iclg.com

8 See imf.org

9 See thebanker.com

10 See africa-press.net

11 See pangea-risk.com (available to subscribers only)

12 See media.afreximbank.com

13 See searchanddiscovery.com

14 See searchanddiscovery.com

15 See documents1.worldbank.org

16 See tradingeconomics.com

17 See azule-energy.com

18 See txfnews.com

19 See furtherafrica.com

20 See documents1.worldbank.org

21 See ibanet.org

22 See reuters.com

23 See ibanet.org

24 See ibanet.org

25 See trade.gov

26 See trade.gov

27 See country.db.com