23 April 2020

Covid-19 has shaken up the world’s commodities sector despite price volatility being no stranger to its market participants. Reduced demand from an economic slowdown has meant falling prices, lack of investment, and logistics log jams. Clarissa Dann reviews Deutsche Bank research and highlights overall fundamentals

Commodity markets are volatile and commodity traders always like volatility and the contango where the spot price is lower than the forward price. Covid-19 has sent most commodity prices tumbling – but history teaches that a bounce-back will come – this time when Covid-19 stops suppressing economic activity.

When global production stops, the requirement for input to production declines and the market does exactly what it ought to, something we can see played out by the crude prices, low demand, insufficient storage and the price behaviour.

However, in a world where around a third of its inhabitants are in some sort of lockdown, an uptick in transport-related demand is not exactly round the corner. Energy and industrial metals have seen significant price contractions (while the gold price goes the other way as investors seek safe havens), while food security is threatened in economies where manpower displacement affect planting and harvest cycles.

What does this mean for commodities? Global GDP is underpinned by the access to and revenues from commodities asset conversion and trade, creating a labyrinth of interconnected supply chains. Crude oil is refined to power automobiles and aeroplanes – but lockdown keeps consumers off the roads and out of the skies. Vegetables are dumped as mass-market farmers find their commercial clients have no customers to service – but many supermarket shelves are bare. From farm to fork, from “rare earth” mineral to computer chip, everyone is touched. Covid-19 has changed the dynamics of supply and demand.

However, the world will always need commodities, and that in itself introduces a form of stability. Deutsche Bank’s Global Head of Structured Commodity Trade Finance (SCTF), Sandra Primiero reminds us, “Covid19 is a challenge for all - and being a lender in the commodity industry is insofar comforting in that our corporate clients are well established and familiar with the volatility of commodity prices, and they will also adapt to this new normal.” She continues, “They know that the only stable factor in their industry is that commodities have always been, and will always be needed. And that itself is a source of energy these days.”

However, new deals cannot be structured during a pandemic. “At Deutsche Bank we never structure and syndicate a facility without meeting management and conducting a thorough due diligence. This becomes impossible to do with the plants is shut down and your core external support teams (for example legal and audit) working from home. Videoconferencing just doesn’t cut it,” explains Tasneem Krueger-Vally, Director, SCTF at Deutsche Bank

This article takes a closer look at the trajectory of oil, mainstream industrial and base metals, and provides a snapshot of the logistics issues facing the soft commodities market, with a long-term perspective on what the new normal might look like.

Oil and energy

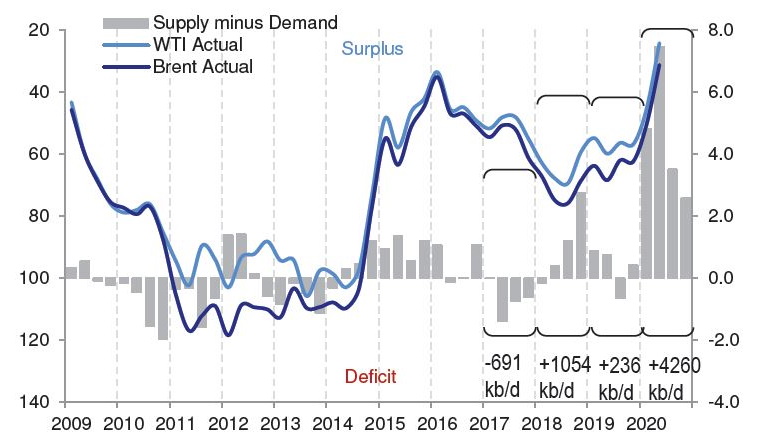

Figure 1: Overwhelming surplus after accounting for OPEC reductions (left axis US$/bbl, right axis mmb/d)

Source: JODI, IEA data from Monthly Oil Data Service OECD/IEA 2020, www.iea.org/statistics Licence: www.iea.org/t&c; as modified by Deutsche Bank

At one point on 20 April the May contract for West Texas Intermediate (WTI), the US oil benchmark, which had started the day at US$17.85/bbl traded at –US$39.55/bbl, remaining in negative territory for around six hours before recovering to US$1.43 the next morning. Oil is traded on its future price and given that futures contracts were due to expire on 21 April, traders took steps to avoid having to take delivery of the oil and incur storage costs when storage capacity is running out fast.

“The US may now be considered the epicenter of both the pandemic and crude-oil oversupply, with the WTI May contract trading to US$-37/bbl today. Similar stresses could occur in other regions but may not be as evident, owing to less transparent market data and pricing,” observed Deutsche Bank Analyst Michael Hsueh in his report Hseuh on Oil: Perfect storm has landed the day it happened. Macro Strategist Jim Reid added in his Early Morning Reid (21 April) that this was, “one of the more remarkable moments in financial history and that is a deeply negative oil price - that is paying someone to take delivery”.

Brent, the benchmark used by the rest of the world, was trading at US$26/bbl as at 20 April, despite the 12 April deal between the world’s energy superpowers in the form of OPEC and its allies, including Russia to broker a new deal to put in place reductions running until April 2022. As the politics of oil plays out, another interesting phenomenon is the widening differential between the two benchmarks of WTI and Brent.

Global storage is filling up with Reuters predicting on 20 April that US tank space will become a problem if the global oil market remains heavily oversupplied in June 2020 and beyond.1 Storage capacity in the refined fuels system is lower with tougher logistics constraints, and when full, says the report, “refineries will have no choice but to cut back crude processing, which will cause crude stocks to back up even more rapidly.

"We have long since entered the zone where previously unthinkable policies have become possible"

“We have long since entered the zone where previously unthinkable policies have become possible, such as any of the following disruptive risks: A breakdown of the US-Saudi strategic relationship, US oil tariffs on imports from GCC or OPEC+ countries, or US government subsidies paid to oil companies not to produce,” reflects Hsueh.

“Further OPEC action may not be forthcoming because the decision to reduce output in May is already stretching the limits of both what is operationally possible, fiscally acceptable, and plausible to market participants. With OPEC possibly having reached its limits, and a recovery global demand yet to arrive, a more-painful adjustment in non-OPEC supply may be the next most logical event.”

In addition, Deutsche Bank analysts in their Commodities Quarterly: Navigating the Virus Trough question whether the production cut will last. “We have doubts over Russian compliance which has previously struggled with much smaller cuts. In addition, signs of disunity from unidentified OPEC members declaring that they were 'blindsided' by the deal does not bode well for the deal's compliance and longevity,” they reflect, adding that they see a further slide of Brent to US$25/bbl “if not further” over the coming quarter.

Although the imbalance between oil and gas demand and supply is restructuring energy markets, the need for a reliable electricity supply is more acute than ever as millions work from home, e-commerce sites become the new shop front and streaming services take over from cinemas and theatres. As Fatih Birol, Executive Director of the International Energy Agency puts it, “The huge disruption caused by the coronavirus crisis has highlighted how much modern societies rely on electricity."2

He goes on to point out that government stimulus plans drawn up to counter the economic damage from the coronavirus “offer an excellent opportunity to ensure that the essential task of building a secure and sustainable energy future does not get lost amid the flurry of immediate priorities.”

This point is developed by the International Renewable Energy Agency (IREA): “Transforming the energy system could boost cumulative global GDP gains above business-as-usual by US$98trn between now and 2050. It would nearly quadruple renewable energy jobs to 42 million, expand employment in energy efficiency to 21 million and add 15 million in system flexibility,” said Francesco La Camera, IRWE Director General upon the publication of it first Global Renewables Outlook on 20 April.3

In The oil industry, a view of the future (18 April)4 The Economist further develops this theme of systemic change. It suggests that the Covid-19 crisis could dampen long-term demand for oil and the sustained period of homeworking with fewer flights and urban pollution “could help change public opinion about the desirability of a faster shift from an economy built on fossil fuels”. In other words, oil producers need to get used to the idea of low demand as governments move to limit climate change. “Oil producers should see Covid-19’s turmoil for what it is: not an aberration, but a sign of what is to come.”

Metals and mining

China’s appetite for industrial commodities has grown exponentially ever since its economic reforms in 1978 as it grew to become the world’s second-largest economy. The country has evolved along its economic growth pattern from a rural and agricultural economy, to urban, industrial and service. The needs of its 1.4 billion population has driven a manufacturing and construction boom, making it the world’s largest consumer of industrial metals, namely aluminium, nickel, copper, lead, iron ore (smelted to make steel) and zinc. In addition, China is a significant producer – and has been investing in its own metals production, improving technology to reduce the negative impact of the coal-fired smelters on the environment, something illustrated in the flow article Blue-sky thinking – a corporate profile of Qiya, a Chinese aluminium producer.

Covid-19 has impacted the appetite for metals and mining products (as mentioned above, excepting gold due to its safe haven investment status) all over the world, but with China consuming and producing so much of it, both the drop and expected future uptick of Chinese demand affects the whole industry. As the People’s State comes out of Covid-19, observers are seeing Chinese manufacturing, metals and mining companies getting back into operation, helped by lower energy costs as a result of the slumping oil price.

Nicholas Snowdon, Metals Research Analyst, Deutsche Bank explains Chinese metals demand on Trade Finance TV

In his interview with Trade Finance TV (recorded 10 February 2020), Deutsche Bank’s Metals Analyst Nick Snowdon explains how the past two years had been tough for metals demand overall because of the slowdown in manufacturing worldwide, aggravated by US/China tensions. However, “towards the end of 2019 we saw two positive trends”, says Snowdon. These were: a broad uplift in manufacturing trends in China, the US and Europe and, “a step forward in US/China trade relations”. He also points out that the lack of confidence in global manufacturing had resulted in firms destocking and acting on a hand-to-mouth basis. Before the full force of Covid-19 hit, broader growth trends were predicted during December 2019 for the year ahead. “Beijing was channelling support for a pick-up in infrastructure investment – such as the transit network and port development” reflects Snowdon.

Copper

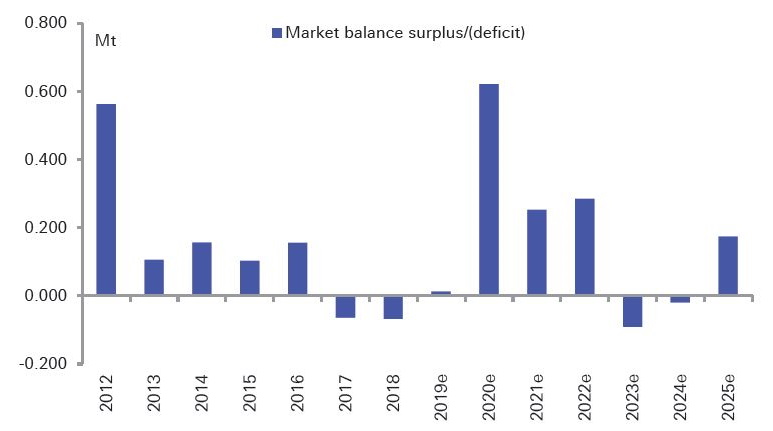

Figure 2: Global refined copper market expected to be in a multi-year high surplus in 2020

Source: Deutsche Bank, Wood Mackenzie

Copper, agreed Snowdon, is something of a bellwether of other industrial metals. “On the demand side, it’s all about China and represents 50% of global demand, but on an annual basis drives 90% of demand growth. It’s all about what is going on in the Chinese economy.” When the interview was recorded, he was already seeing market dislocations arising from Covid-19 but it was not clear at what point stabilisation would occur and China would get back to business as usual. As for supply of copper, he explains, the past three years has seen no growth in supply because of the lack of investment from mining companies in new projects. So if demand growth eventually happens and supply remains static, there are, he predicts “the ingredients for tight fundamentals and price support”.

However, just over a month after this interview was recorded, the full impact of Covid-19 was becoming clearer. In Redrawing the base metals and bulks outlooks for the Covid-19 shock (19 March 2020) Snowdon and his team state, “Our projected base metal 2020 market balances have softened substantially, with sizeable metal surpluses now expected for copper, aluminium, nickel and zinc versus deficits or balanced markets projected pre-virus”. And the supply issues remain: “At the current juncture, China is already providing a sequential positive demand influence, while supply adjustments are not simply a function of low prices but also virus- related disruptions which will be substantial”. In other words manpower dislocation has not just affected food production, but metal production as well.

By 15 April, the sustained lack of demand is more pronounced. In Commodities Quarterly: Navigating the virus trough, the Deutsche Bank Commodities analysts reflect, “Short term supply disruptions have provided a material counter tightening effect for both copper and zinc, but as these constraints lift and the demand revival likely lags, greater surplus evidence is likely to emerge.”

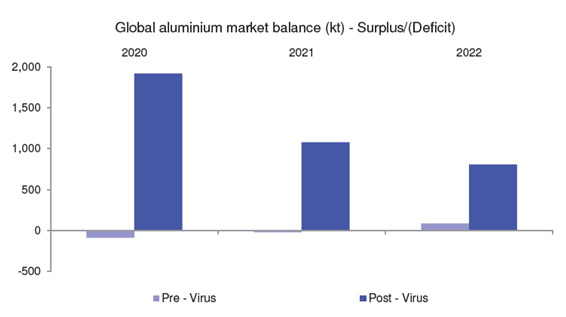

Figure 3: Aluminium market balance expectations have swung sharply into surplus for the next three years

Source: Deutsche Bank, Wood Mackenzie

The picture is worse for aluminium – as a result of what analysts call “supply ill-discipline”. The analysts explain, “The aluminium market had already faced a relatively weak demand environment for the past two years, primarily tied to the auto sector, and conversely was facing a trend of expected strong production on a phase of new smelting capacity additions in 2020-21. With the additional negative adjustment to ex-China demand conditions alongside the deflationary cost effects form weaker energy and alumina prices there is little doubt that aluminium prices are likely to remain compressed for a sustained period of time.”

Iron ore

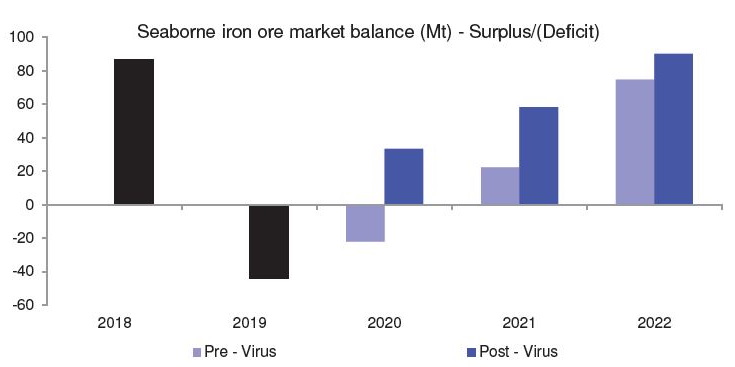

Figure 4: Modest iron ore surplus now projected for 2020, weighted towards H2

Source: Deutsche Bank, Wood Mackenzie

As for iron ore, the Deutsche Bank Research team project a 31 million tonne full year surplus for 2020, but this, they say, is “a small surplus relative to market size” and thus for the near term “the market will remain tight”. While ex-China steel demand has been downgraded for Q2, Chinese steel demand will represent “a material offset” given its current trends and the “stimulus leverage”. They point out that 20 million tonnes was cut from global supplies of the commodity in Q1 “from a combination of disruptions in Australia, Brazil and China (mine/scrap)”. However, they conclude, “virus-related disruptions will be substantial for iron ore”.

"Commodities have always been, and will always be needed"

Soft commodities

In developed economies, empty supermarket shelves bring home to consumers how fragile global food supply chains are, and in developing ones lack of food security hold those countries back from achieving their potential and reducing poverty.

Covid-19 has presented a huge disruption to many supply chains of food inputs. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations explains, “A protracted pandemic crisis could quickly put a strain on the food supply chains, which is a complex web of interactions involving farmers, agricultural inputs, processing plants, shipping, retailers and more. The shipping industry is already reporting slowdowns because of port closures, and logistics hurdles could disrupt the supply chains in the coming weeks.”5

Multinational food production corporations are making it their business to step up to the challenge to keep their end customers supplied. “We have a duty to ensure that much-needed food, pet food and beverage products are available around the world. To achieve this, we are working closely with our supply chain, distribution and retail partners,” said a Nestle spokesperson on 8 April.6

A similar stance emerges from the US Department of Agriculture amid headlines of large scale food wastage as educational and hospitality industries stop taking bulk deliveries. “Dairy Farmers of America, the country's biggest dairy co-operative, is estimating that farmers are having to dump 3.7 million gallons (14 million litres) of milk every single day because of disrupted supply routes. This issue is not only being seen in the US, with dairy farmers in the UK asking for government help because of their own surplus problems,” noted BBC News on 13 April.7

The World Bank estimates the 2018 total of malnourished people at 820 million – up from 784 million in 2015. It estimates that demand for food will increase by 70% by 2050 and at least US$80bn in annual investment will be needed to meet the demand, “most of which needs to from the private sector”.8 “New shocks related to climate change, conflict, pests (such as locusts and Fall Army Worm) and infectious diseases (such as Covid-19 and African Swine Fever) are hurting food production, disrupting supply chains and stressing people’s ability to access nutritious and affordable food, raising fresh concerns for food security in 2020,” it reports.9

Banks, sometimes in partnership with development finance institutions such as the World Bank provide credit facilities and financing (deploying trade finance, payables finance and commodity finance techniques) for farm operators, trading companies and food processors. They also facilitate investment opportunities covering the entire value chain in agriculture, including in innovations and technology.

However, agricultural commodities are some of the most difficult commodities to finance because of storage and logistics issues, compounded by potential country risk issues in some economies. As a result, financial institutions in developing economies lend a disproportionately lower share of their loan portfolios to agriculture, compared with agriculture’s share of GDP.

As the industry moves towards digital solutions for performing Know Your Customer checks and getting trade finance through to the smaller provider, these obstacles could finally be addressed.

Summary of Deutsche Bank Research reports referenced

- Hsueh on Oil: Perfect storm (20 April) by Michael Hsueh

- Early Morning Reid: Macro Strategy on 21 April 2020 by Jim Reid

Commodities Quarterly: Navigating the Virus Trough (15 April) by Nick Snowdon, Liam Fitzpatrick, Chris Terry, Bastian Synagowitz, Sathish Kasinathan, and Corinne Blanchard

Deutsche Bank clients can access the full research reports here

If you would like access do contact a Deutsche Bank sales representative

Sources

1 See https://reut.rs/3i2qIEn at reuters.com

2 See https://bit.ly/342jN8W at iea.org

3 See https://bit.ly/2EwwlNc at irena.org

4 See https://econ.st/3i8SUFG at economist.com

5 See https://bit.ly/36a4az1 at fao.org

6 See https://bit.ly/3i62CbE at foodnavigator.com

7 See https://bbc.in/2GbTXaA at bbc.com

8 See https://bit.ly/3mQKrKD at worldbank.org

9 See https://bit.ly/32YDoaR at worldbank.org

Go to Corporate Bank EXPLORE MORE

Find out more about products and services

Go to Corporate Bank Go to Corporate BankStay up-to-date with

Sign-up flow newsbites

Choose your preferred banking topics and we will send you updated emails based on your selection

Sign-up Sign-upSubscribe Subscribe to our magazine

flow magazine is published annually and can be read online and delivered to your door in print

You might be interested in

MACRO AND MARKETS

Central banks: on-side or outside? Central banks: on-side or outside?

How much “support” should central banks give Covid-19 stricken economies? With the focus on fiscal responses, what tools remain in the monetary policy armoury? flow´s Clarissa Dann reviews Deutsche Bank Research insights

Trade finance and lending {icon-book}

Saving trade Saving trade

As the Covid-19 pandemic wreaks havoc on economies and communities – and ultimately global trade, what is the impact on trade finance and supply chains? Geoffrey Wynne explains

Trade finance and lending {icon-book}

Sunset to sunrise Sunset to sunrise

Just because the oil majors are withdrawing from the North Sea, that doesn’t mean there is no extraction. Clarissa Dann looks at how reserve-based lending is supporting the smaller independent oil producers that are thriving in the region