19 April 2023

With fraud fast becoming one of the biggest risks for global trade, flow’s Clarissa Dann takes a closer look at the vulnerability of trade finance to criminals and protection measures being deployed

MINUTES min read

Professional fraudsters are increasingly taking advantage of the trade industry’s reliance on document-based processes, using techniques such as fake invoices, fake bills of lading, collateral fraud, and duplicate financing to get the better of banks and their clients. These practices are on the rise, with some of the industry’s largest ever fraud scandals having occurred over the past few years.

“Banks screen the applicant, beneficiary, the counterparty bank, the transport company, the vessel, the ports and port owners and the goods being transported to identify any sanctions issues. This information is not static and over the course of a transaction could change multiple times – creating due diligence and record keeping challenges,” reported PwC in their 2016 report Trade finance Understanding the financial crime risks.1 To add further complexity, it noted, the fair price of goods will often be subjective and difficult to determine, especially as prices can vary across different territories and may be driven by forward contracts.

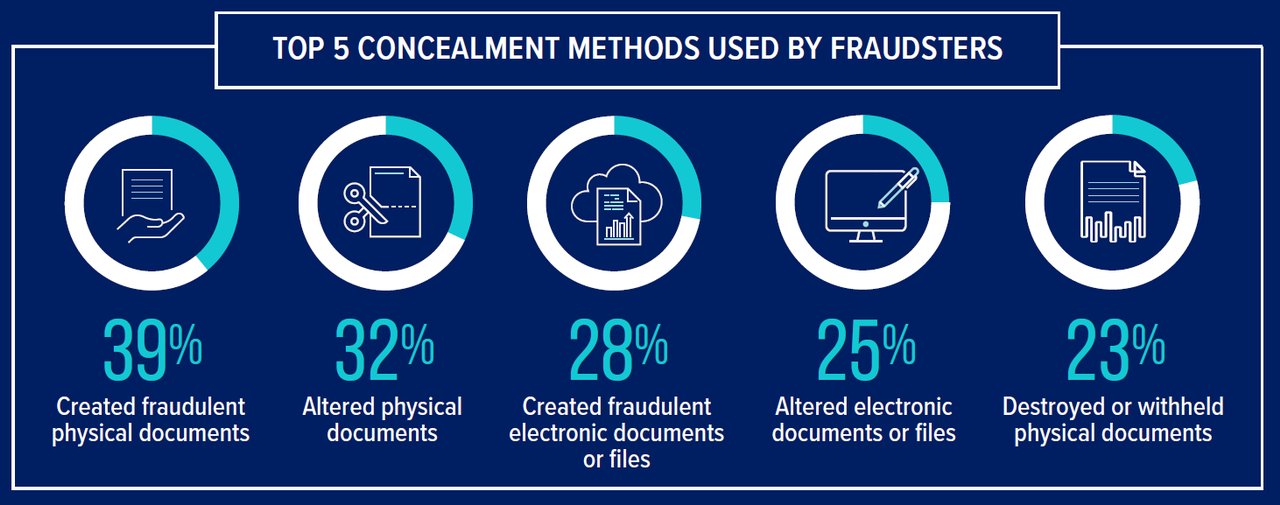

The Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE) highlights the vulnerability of documents in general to fraud in their Occupational Fraud 2022: A Report to the Nations.2 The report, published last April , looks at the costs, methods, perpetrators, and outcomes of occupational fraud schemes derived from more than 2.000 real cases of fraud affecting organisations in 133 countries and 23 industries. See Figure 1.

Figure 1: How fraud perpetrators conceal fraud

Source: Association of Certified Fraud Examiners, Occupational Fraud 2022: A Report to the Nations

For each high-profile fraud case, it is not just the company that loses out. The shockwaves are felt across the industry, impacting the many banks and third parties that are involved in trade financing transactions.

Qingdao

One example of this ripple effect was the Qingdao warehouse fraud scandal. This saw the conviction in December 2018 of Chen Jihong, founder and chair of metal warehousing firm Dezheng Resources, who was found guilty on five counts of financial crimes spanning an 18-month period from November 2012 to May 2014. “According to the court statement, his firm accumulated 12.3bn renminbi (Rmb) (US$1.78bn) in funds using either fake warehouse receipts or fake certificates for aluminium ingots, alumina and refined copper at the eastern Chinese ports of Qingdao and Penglai and also raised Rmb3.6bn (US$520.8m) in loans, letters of credit and bank acceptance bills from 13 banks by repeatedly using the same cargoes as pledged collateral,” reported GTR on 10 December 2018.3

When these far-reaching effects are factored in, the true cost of fraud in trade finance becomes clearer. The International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) estimates that if even 1% of the US$5trn global trade financing market is susceptible to fraud – and assuming only 10% of those transactions will lead to losses – this still amounts to an annual cost of around US$5bn in total business disruption.4

Types of trade finance fraud

ICC Commercial Crime Services is often referred to as the anti-crime unit of the ICC and provides an authentication service for trade finance documentation. It also investigates and reports on several other topics, notably documentary credit fraud, charter party fraud, cargo theft, ship deviation and ship finance fraud. Michael Howlett, CEO and Director of its International Maritime Bureau (IMB) is well known on the trade finance conference circuit and, according to his biography, “has been instrumental in identifying systematic international fraudsters, invited to provide evidence and appear as a witness in trade related criminal cases and assisted in the investigation of the largest fraud in trade finance history”.5

“Ultimately it is a human that defrauds and not the system used”

Howlett explains that the trade finance frauds witnessed today are much more sophisticated than the traditional scams seen decades ago.

“The biggest problem remains collusion between related parties. Banks are often the targets of such frauds,” says Howlett. “Deals that appear to be arms-length transactions turn out not to be. Because the IMB sees suspect transactions from across the banking industry globally, patterns of major fraud schemes become more apparent than those restricted to a single bank’s transactions or from a single jurisdiction,”.

Furthermore, he points out, whether it is a paper or an electronic bill of lading, “ultimately it is a human that defrauds and not the system used” with the frauds seen today being in the documents. In other words, “where there is collusion and deliberate intention to defraud from the outset, it will be extremely difficult to prevent abuse, however robust the system”. He confirms that the IMB has seen “a worrying increase in cloned bills of lading”.

As shipping information – such as vessel movements and cargo details – become increasingly transparent, cloned bills of lading are used by fraudsters to extract monies from the banking system. Routine checks into vessel movements and cargo operations can deliver a positive response – even when the bill of lading presented to the bank is, in fact, incorrect.

“We see this in both containerised and bulk shipments,” Howlett reports. “Cloned bills of lading are used in dubious schemes such as “synthetic letters of credit”, money laundering, frauds in which the bank could be the ultimate victim of collusion between buyers and sellers.

“We feel this is perhaps where our efforts should be focused to ensure that the bills of lading presented are in fact the operative documents.” He is worried that, despite the improved efficiency and faster trade transactions that electronic bills of lading facilitate, “Eb/ls will not, however, change the nature of fraud and, in many ways, could accelerate it”.

The widening trade finance gap

One of the most visible impacts of rising fraud cases has been the reduction in the provision of trade financing from banks. In August 2020, GTR reported on Dutch bank ABN Amro’s decision to withdraw entirely from the trade and commodity finance markets and shed 800 jobs, having sustained several heavy losses that included a fraud case involving commodities trader Agritrade.6 Others, including Société Générale and BNP Paribas, have scaled back or consolidated commodity finance offerings, removing more than US$20bn of available liquidity from the market.7

As a result, small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are increasingly struggling to secure bank financing, with the Asian Development Bank (ADB) finding that this segment accounts for 40% of rejected trade finance requests.8

Speaking at a Bankers Association for Finance and Trade (BAFT) event, Michael Hogan, Managing Director of fraud prevention tech specialist MonetaGo summed up the situation: “when fraud scandals happen, the brakes go on, banks lose money, credit lines are reduced, and pricing goes up. But then that pain is not shared equally across the board. Generally, the SMEs take the biggest hit because they can't shop around and get the facilities elsewhere.”9

As banks step back and SMEs find it increasingly difficult to access financing, there are growing concerns about the widening trade finance gap, which already reached a record US$1.7trn in 2022.10

Improving onboarding

Efforts have long been underway to develop standards to meet specific industry pain points, such as those related to customer onboarding. It is, for example, a regulatory requirement for banks to perform know-your customer (KYC) checks on their correspondent banks, as well as their corporate customers – and these play a significant role in reducing the risk of onboarding customers involved with illegal activities, such as money laundering, fraud or terrorist financing. The challenge, however, is that in trade finance much of the work involved in confirming counterparties' identities has historically been manual, time-consuming, and prone to human errors.

So, what is being done to improve these checks? One example is the supra-national not-for-profit Global Legal Entity Identifier Foundation (GLEIF) project, which since 2014 has worked to significantly reduce the workload around existing KYC and anti-money laundering (AML) onboarding procedures. The project assigns each legal entity in the world a unique identifier – known as the Legal Entity Identifier (LEI).11 This helps to automate identity verification and can be used by banks, for example, to trace outstanding invoices and identify suspicious activity, such as multiple invoices for the same shipment (see more on this topic in the flow article Who is your counterparty?). The standard is now well established, and the focus for the industry going forward is on growing the quantity of LEIs within the global trade ecosystem.

In recent years, customer confidentiality policies, which prevent banks from sharing crucial information, have also reduced the effectiveness of KYC checks – and led to a rise of duplicate financing cases. Without a central register, fraudsters can take documents from one bank, shop them around to multiple banks and, in return, get multiple financings.

In response, some countries are now developing blockchain-based data registries. Singapore, for example, launched their pioneering Trade Finance Registry (TFR) in 2020, which allows each bank participant to validate whether another financial institution has already submitted a particular title instrument for financing purposes. Underpinned by blockchain technology, banks can share this data so that it does not violate client confidentiality and compliance rules, while still reducing the risk. The Registry is being built by MonetaGo.12

Swift has also established its own data registry – the KYC Registry – which since its December 2019 launch has become the accepted standard for correspondent banking due diligence, with almost 6,000 financial institutions using it to date.13 The registry aggregates KYC information in a globally recognised, standardised format and provides corporates and banks with access to a standardised Correspondent Banking Due Diligence Questionnaire (CBDDQ) produced by the Wolfsberg Group, an association of global banks aimed at promoting the development of effective anti- money laundering (AML), KYC and counter-terrorist-financing standards. This enables banks to implement a reasonable standard for cross-border due diligence and reduces additional data requirements.

“What the LEI and Swift’s KYC Registry demonstrate is that the industry as a whole has successfully started and is continuing to jointly work on solutions that mitigate the risk of fraud,” says Christian Ressel, Non-Financial Risk Center of Expertise (NFR CoE), Trade Finance, Deutsche Bank. “By broadening the perspective of each party participating in a certain transaction, collaboration will be the key to further combatting financial crime,” he adds. In view of this, the next step for the KYC Registry – as with LEIs – is to further drive adoption to improve the accuracy and reliability of the tool.

Is enough being done?

It is not just onboarding processes that are being reviewed. New technology solutions – provided by fintechs – are helping to make the entire trade financing chain more transparent and less manual, which, in turn, is helping compliance teams to seamlessly access the information they need to manage fraud risks.

Yet for these new solutions to have a real impact on trade finance, greater collaboration – not just with banks, but also among technology providers – will be needed to ensure that the solutions can be integrated into the existing ecosystem. Trade finance industry associations, such as BAFT, the ICC and the International Trade and Forfaiting Association (ITFA) have a key role to play in fostering such collaboration.

According to André Casterman, Chair of ITFA’s Fintech Committee, industry associations have a duty to find a way for the various existing and emerging technologies to interlink. “The best new innovations are the ones that can combine the strengths of the existing technologies and bring a very specialised and very focused value proposition to address a specific pain point, such as indeed, fraud prevention,” he observes.

Industry bodies are also able to make a unique case to policymakers for what advantages new technologies or laws can bring to the table. Policymakers can, in turn, then work to mandate certain actions – such as regulatory reporting and data sharing – that can play a key role in supporting fraud prevention. This is especially important in instances where existing policies present an obstacle to digitalisation efforts.

Take for instance, the UK government’s planned Electronic Trade Documents Bill. Until the bill is passed, trade finance documents, such as bills of lading and bills of exchange, must be paper-based due to longstanding laws.14 Without removing the legal obstacle to electronic versions of trade documents, these valuable tools cannot be adopted – no matter how useful the technology might be.

“There is a need for clearer fraud prevention policies not just at a local level, but at a regional or global level”

There is also a question as to whether there needs to be more of a united front when it comes to legislation that can assist firms in the fight against fraud. “We might see an issue in one of our trades, but there isn’t always an obvious way for us to address it,” explains Fred Dons, Senior Sales, Commodity Finance Flow in Deutsche Bank’s Natural Resources Finance team. “Picture this scene: a banker with operations in Amsterdam is financing an exporter based in Hong Kong who is shipping goods to Hamburg. If something happens during the transaction that raises alarm bells, such as a bill of lading not being paid on time, who can the bank turn to for help? If I go to the Amsterdam police, they will say it’s out of their jurisdiction and if I go to the Hamburg police, they will say they cannot help because the vessel is not yet in Germany, and so on. There is, therefore, a need for clearer fraud prevention policies not just at a local level, but at a regional or global level as well.”

The human touch

Digitalisation and legislation, while important, are not necessarily the silver bullet for trade finance – and the human element remains critical. “Being able to identify potential fraud is just one of the steps: knowing what your client is doing and being able to recognise odd patterns is the second and being close to the actual trade is the third,” adds Dons.

While Deutsche Bank has innumerable automated checks and balances in place, experience still wins out when it comes to discovering and acting on unusual client patterns. “Trade Finance practitioners with decades of experience cannot currently be completely substituted with any single technology solution on the market,” says Ressel. “And even for the most sophisticated system, there is always a human at the beginning of the process that is interpreting the outcomes.

“As we have seen in recent years, even corporates that at one time were above suspicion have been unwillingly caught up in fraud, for example when a rogue trader has blown up the balance sheet,” says Dons. In February 2023, Trafigura – a commodity trading company – issued a statement detailing the “systematic fraud” that it estimates will cost the business around US$577m.15 “The fraud concerns containerised nickel in transit during 2022 and involved misrepresentation and presentation of a variety of false documentation. The fraud is isolated to one specific line of business. We have seen no evidence to suggest that anyone at Trafigura was involved or complicit in this illegal activity,” said the trading company in a statement (9 February 2023).

This recent case yet again underlines the importance of physical checks. Deutsche Bank, like its peers, aims to get as close as possible to the actual transactions it is financing when red flags are raised. This includes vessel tracking, whereby the bank checks where the cargo being financed is currently located, where it is coming from, and where it is going. Within the commodity space, Deutsche Bank – or a reputable third-party surveyor – also visit warehouses to confirm that the cargo is stored there.

“Ultimately, you cannot check every vessel or warehouse for every transaction,” says Ressel. “That is why our strategy fights fraud on multiple fronts: our robust systems and automated processes help to detect fraud, and our experienced trade finance practitioners can help to manage the investigation.”

Sources

1 See pwc.co.uk

2 See acfepublic.s3.us-west-2.amazonaws.com

3 See gtreview.com

4 See iccwbo.uk

5 See ics-shipping.org

6 See gtreview.com

7 Shutting fraudsters out of trade, by the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) UK, the Centre for Digital Trade and Innovation, and MonetaGo

8 See adb.org

9 BAFT Connect webinar entitled “Shining the Spotlight on Fraud in Trade”

10 See weforum.org

11 See "Who is your counterparty?" at flow.db.com

12 See gtreview.com

13 See swift.com

14 See gov.uk

15 See trafigura.com

Trade finance solutions Explore more

Find out more about our Trade finance solutions

solutions

Stay up-to-date with

Sign-up flow newsbites

Choose your preferred banking topics and we will send you updated emails based on your selection

Sign-up Sign-up