05 July 2023

Despite political upheavals, Latin America is enjoying renewed growth, as firms shore up supply chains with nearshoring and mitigate currency volatility and inflation. LatAm correspondent Ivan Castano Freeman reports for flow

MINUTES min read

Latin American companies are rushing to fund expansion and slash risks from volatile currencies, as they move to profit from nearshoring opportunities amid sluggish economic growth.

The trend is boosting financing opportunities for global lenders, including Deutsche Bank, which is working to structure deals in its key markets of Mexico, Brazil, Colombia and Chile. The bank sees opportunities to provide foreign exchange and derivatives services for corporate treasurers, including fixed income, interest rate swaps, cross-currency swaps and FX forwards.

“There are several transactions we are working on with clients,” says Isander Santiago-Rivera, Head of Deutsche Bank’s Institutional Client Group-Fixed Income Ex-Brazil/Mex at the Investment Bank. For instance, a Peruvian firm is currently looking for ways to import raw materials from China while circumventing the transaction’s potential currency headwinds.

“They want to purchase products in Asia, but it can take up to three months for them to arrive in Peru,” explains Santiago-Rivera. “During that time, the dollar can appreciate, raising their purchasing costs as they earn in soles. If they sign a forward purchase agreement with us, we can guarantee a fixed currency rate for the transaction so they can focus on their business.”

Post-Covid bounce

Historic market volatility, coupled with rising interest rates in the US and Latin America, have boosted appetites for complex corporate financings, according to bankers.

“After Covid, companies started to import more from other countries,” says Santiago-Rivera. “But because of the high volatility in all asset classes, there is a greater need to purchase products in ways that limit this.”

“Any kind of hedging or risk mitigation solution will continue to be in high demand”

Strong prices for the region’s top commodities (such as crude oil, and metals including copper and, increasingly, lithium), mean trade finance could gain sharply this year. Given this backdrop, Ignacio Ramiro, Managing Director for Structured Trade & Export Finance at Deutsche Bank, expects demand for the bank’s bread-and-butter trade products, such as short-term guarantees, working capital and letters of credit, to remain strong in 2023.

Amid the stated currency risks, his Madrid-based team is busy structuring joint financings, such as those marrying trade finance loans with interest-rate and FX hedging. “We are living through a period of instability that affects both interest and exchange rates, so any kind of hedging or risk mitigation solution will continue to be in high demand,” he notes.

Global currency volatility has become so acute that Argentina and Brazil, South America’s largest economies, announced plans for a common currency to finance transactions in the troubled Mercosur free-trade bloc; the plan could eventually include two other members, Uruguay and Paraguay. In an interview with the TV channel GloboNews given in January 2023, former Brazilian Finance Executive Secretary Gabriel Galipolo stated that the proposal had “nothing to do with replacing national currencies”, but rather that “the current low convertibility of the Argentine peso motivates the teams to think today of another form of unit of account, looking to foster trade between the two countries.” He added, “Today, the risk for Brazilian exporters is convertability.” The talks are still at an early stage.

Nearshoring focus

Meanwhile, financial institutions are rushing to finance growth-hungry corporates in Mexico that are keen to move away from ‘just in time’ logistics to ‘just in case’. Nearshoring, which essentially means manufacturing close to markets, is taking off as the US/China trade conflict continues – impacting the ability to source products from China.

Because of this, local bank Banorte expects to bolster Mexican shipments by US$34bn annually, propelling Latin America’s second-largest economy into a new era of prosperity. Altogether, the shift, which is seen as benefiting the Aztec nation’s automotive, computer, transport, electric and telecoms export sectors more strongly, is expected to add US$168bn of shipments by 2028, the bank said in a research report. On 26 March 2023, Banorte’s Chairman and Regular Director, Carlos Hank González, told Reuters that the bank was adding 800 people to the workforce “just to be able to capitalise on the opportunities for nearshoring”.

“There is high interest from companies in the Northern (US border) region to grow exports,” confirms a second Carlos González, Research Director at Mexican investment bank Monex, adding that industrial real estate firms, or so-called Fibras, which are leading gains in the Bolsa da Madrid (the Spanish stock exchange), are rushing to procure funding to enlarge industrial facilities. “Many of the industrial and manufacturing parks in the country are at 100% capacity,” González adds. “We need much more infrastructure lending and investment.”

In order to not miss the boat, Monex is ramping up its cash management, factoring and other investment banking activities, confirms Business Head Alejandra Pérez, adding that the firm is eyeing “many opportunities”.

Mexican strength

The Americas Deutsche Research team expects Mexico to benefit most from the global supply chain reshuffle. Proximity apart, the country is hugely integrated with the US and has a long-running free-trade agreement. This is the former North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) that became the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement on 1 July 2020. This has helped helped cross-border trade expand by 20% annually in recent years.

The team notes that more corporate activity and more investment projects will bring an increased need for banking services, including cash flow financings and FX hedges. These could also feature solutions for foreign units of large corporations that need to repatriate profits in diverse currencies.

If nearshoring fully materialises, Mexico – which posted a GDP of US$1.4trn in 2022 – could outpace growth in neighbours suffering from a marked slowdown. These countries include Colombia, which will see a huge growth drop to 1.0% this year from 7.5% in 2022, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF). It will be followed by Chile, whose economy is forecast to sink by 1.0% versus a 2.4% gain last year. Meanwhile, Mexico and Brazil will see gains of 1.8% and 0.9% respectively, compared with just over 3% last year, the IMF adds.

Deutsche Bank Research notes that Latin America’s flagship currencies, such as the Mexican peso and Brazilian real, will end the year higher than the dollar, as the greenback continues to weaken and central banks end a rate-hiking spree to curb inflation.

Exports, meanwhile, will trend higher as commodity prices remain high, benefiting metals exporters in Chile and Peru as well as oil producers in Mexico, Colombia and Venezuela.

Lithium boom

Lithium could become a star Latin American export as countries such as Bolivia, which has the world’s highest reserves of the new ‘white gold’ that is used to make electrical vehicle batteries, race to develop manufacturing and export capabilities. Indeed, Bolivia recently struck a US$1bn deal with China’s leading battery maker, CATL, to churn out 100,000 tons of lithium by 2028, a feat that could transform its impoverished economy.

The stakes in the lithium race are so high that Chile, the world’s second-largest producer after Australia, has announced that it will nationalise its industry, making lithium a more crucial growth prong than copper, the sales of which are declining.

But there will be obstacles, mainly technical and political. The challenge for Peru and Chile is to add value by eventually producing lithium batteries for export, not just raw materials.

After years of upheaval, analysts see Latin America’s political landscape stabilising. Lithium apart, Chilean political risks have diminished, while calls demanding the resignation of Peruvian President Boluarte have quietened down. Given that she only took over from Pedro Castillo in December 2022, following his removal after impeachment, this does suggest a period of comparative calm.

Despite protests against a string of reforms, Colombia doesn’t face the same calls for radical constitutional or structural overhauls that have hit Chile and Peru. In Brazil, there is no “existential threat” after President Lula won his third term, notes Deutsche Bank Research, while democracy and peace are prevailing in Mexico.

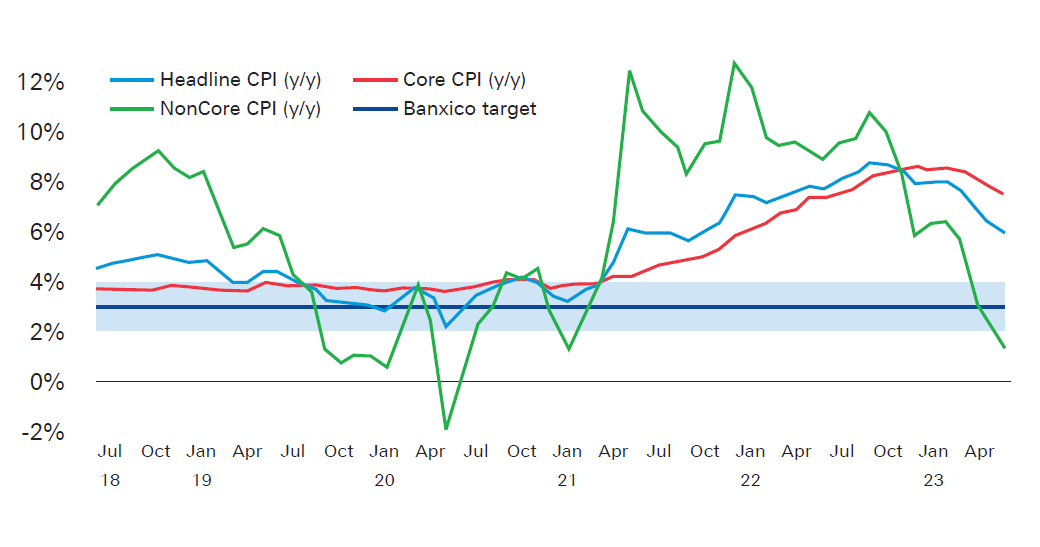

Figure 1: Mexico – inflation slowly easing

Source: Deutsche Bank Research

Moving on up

Deutsche Bank’s confidence in the region is illustrated by the expansion of its workforce and movement of capital into Latin America, according to Ricardo Cunha, Head of Emerging Markets for Brazil. He told Bloomberg in December 2022 that the bank “began strengthening its operations in the region recently, with the addition of new staff in Brazil to look after hedge funds, onshore fixed-income and commodities, in addition to currencies and derivatives local trading activities”.

Six months on, the bank’s growth in Brazil has continued. According to Cunha, it spans across: structured credit transactions; FX, inflation/FX/rates/commodity hedging; debt capital markets; and macro coverage of institutional clients. Financing solutions (often related to capex or acquisitions) have been arranged across the digital infrastructure, chemicals, water and sanitation, energy, shipping, oil and gas, packaging and renewables sectors – sometimes with a development finance or multilateral finance partner, Cunha adds.

In addition, the bank has revamped the representative office in Mexico, (see boxout) where the economy continues to grow quicker than expected, while inflation slowly inches towards Banxico’s target (see Figure 1).

Deutsche Bank in Mexico

From left to right: Francisco Martínez, Coverage; Facundo Piña, CFO; Alejandro Gutiérrez, Trader; Xavier Avila, Head of Derivatives Latam; Adolfo Hegewisch, Legal & Compliance; Jorge Mier, COO; Marliz Mejía, CEO; Christiana Riley, former CEO Americas; Jorge Sánchez-Lara, co-head ICG Latam; Cyntia Soto, PA to Marliz Mejía; Carlos Rodríguez, Coverage

After 60 years in the region, as Global Hausbank, Deutsche Bank has refocused its strategy for Mexico, re-entering the Mexican market through a broker-dealer to be able to offer FX and interest rate derivatives locally.

As Mexico’s peso continues to fluctuate against the US dollar amid a recent rate-hiking campaign to fight inflation, “we are helping clients hedge FX and interest rate risks,” notes Marliz Mejia, Chief Executive of the bank’s Mexico office, housed in Mexico City’s Torre Virreyes skyscraper. As an example, “a Mexican corporate can issue a US dollar bond to tap the international markets. Their liability and coupons are in USD but their revenues are in Mexican pesos. In this case we can issue a cross-currency swap to help them hedge the risk of the dollar/MXN rate,” Mejia explains.

Nearshoring opportunities

Nearshoring is gaining traction as the US cuts its reliance on Chinese goods. The trend is expected to bolster Mexican shipments north of the border by US$34bn annually, according to Banorte.

“With companies coming here to install factories, you will have manufacturing services that will require broad infrastructure including energy, data centres, roads, etc.,” Mejia reflects, adding that Deutsche Bank will help fund this new manufacturing ecosystem as it develops.

The enlarged Mexican office will also work to provide corporate treasurers with tailored solutions to help them expand their operations. These firms will include both German clients working with the bank globally, and new Mexican and foreign customers.

Ivan Castano Freeman is a freelance financial journalist based in Bogotá