1 June 2023

Minerals – and their shortages – can make and break supply chains. As nearshoring becomes the preferred strategy for securing essential inputs in times of geopolitical volatility, how does this impact trade flows? Trade economist Rebecca Harding explains

MINUTES min read

The pandemic, subsequent supply chain shortages, and the escalation of the Russia/Ukraine conflict have refocused attention on supply chain resilience. It is now commonplace to hear the phrase “just in case” in logistics and supply chain management.1 Arguably, the whole concept of supply chain management has morphed into a focus on “resiliency”, or “the capability to mitigate most supply chain disruptions and greatly limit the impact of those that occur”.2

Supply chain resilience

Critical supply chains, and particularly those involving rare earth metals, are broader in concept than inventory management, because they are about sourcing components in a supply chain from their very base in raw materials. The US3 and UK governments and the EU have all focused on defining ‘critical supply chains’ since the pandemic. These supply chains are vital to national security in that they ensure food and energy supplies. They also include transition metals and rare earth elements that are core to the digital and renewable future. As tensions with both Russia and China have become more pronounced, improving supply chain resilience and self-sufficiency is becoming a pre-requisite, because there are currently such significant dependencies on those two countries.

In other words, supply chain resilience has become a matter of national security in the US4, the EU5 and the UK6; and a focus for NATO and other allies as well for energy transition, energy security and procurement reasons.7 This shift is material for corporates and for the trade finance providers because, as the role of sanctions and export controls in constraining power has shown, managing supply chain resilience in practical terms means managing new trading routes and partners.

As requirements for sustainability reporting gather pace, these corporates will also be required to develop more alternative energy sources and transition to new ways of operating, if they are to achieve the sustainability and net zero targets set by the Paris Climate Accord and by the regulators who are monitoring the sustainability financial disclosures process. In other words, supply chain resilience is also about achieving supply chain sustainability.

Towards more self-reliance

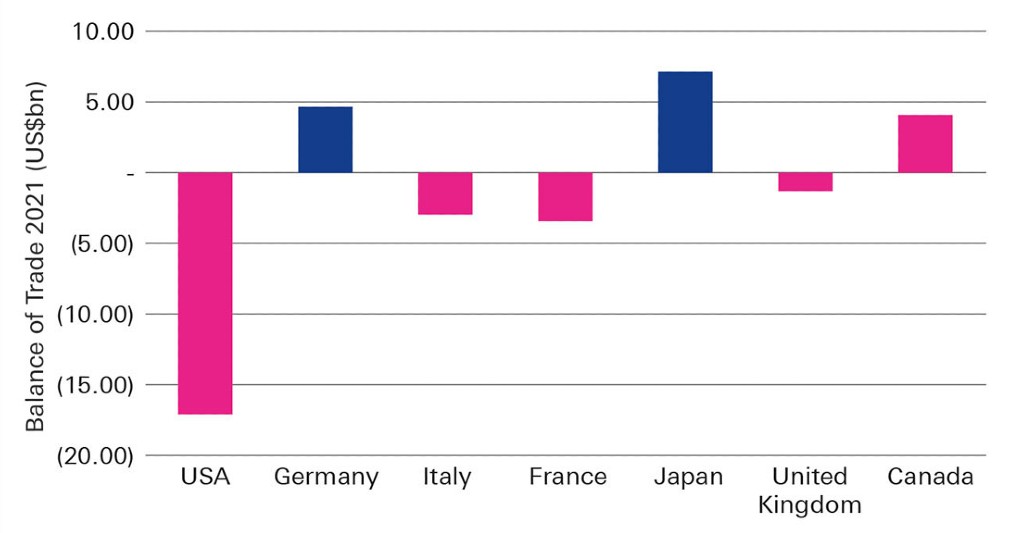

There are multiple reasons why a shift towards more self-reliance within the G7 and beyond is needed (see Figure 1), a point made in the flow white paper, How to ensure commodities in a volatile world (April 2022). In 2021, the G7 had a trade deficit in the critical transition base metals (nickel, copper, aluminium and zinc) of more than US$8bn. While Germany, Japan and Canada had surpluses, the US’s deficit was particularly severe, at US$17bn.

Figure 1: G7 critical transition minerals trade deficit, 2021 (US$bn)

Source: Comtrade

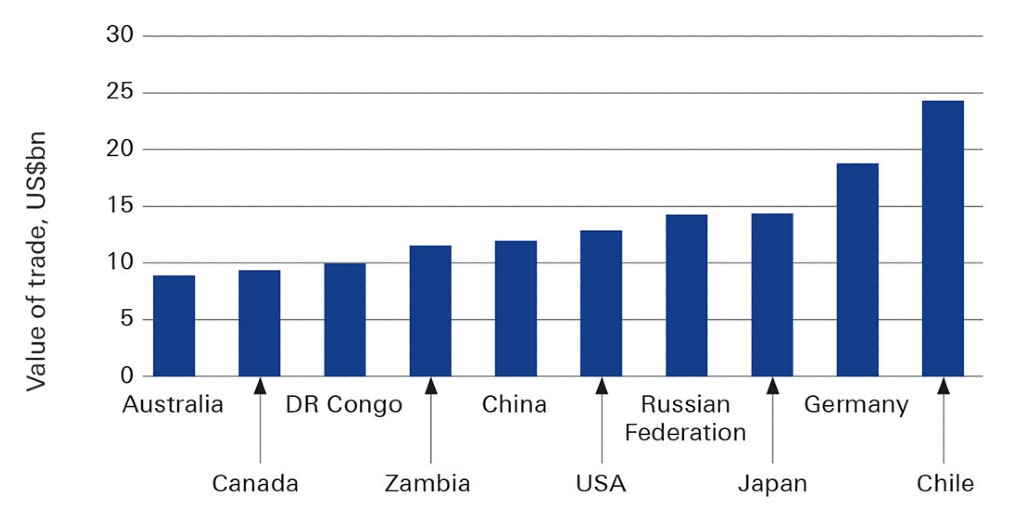

Exports of two transition metals, nickel and copper, are heavily concentrated in the G7 countries and Australia (see Figure 2). Chile is the largest exporter, which may explain why there has been a flurry of diplomatic activity to improve relations between the US and Chile.8

Figure 2: Top ten nickel and copper exporters, 2021, US$bn

Source: Comtrade

Concentration risk concerns

The essence of supply chain resilience is de-risking supply chains so that dependency is distributed and goods are sourced sustainably, in every sense of the word. This issue of distribution is where concerns start to emerge, because of the concentration of capacity in the hands of China, even if, geographically, the production is dispersed.

“Rare metals are used in everyday life and are essential in our transition to clean energy”

For example, China refines some 68% of the world’s nickel, 40% of its copper, 59% of its lithium, and 73% of its cobalt, according to The Economist.9 Similarly, rare metals are used in everyday life and are essential in how we transition to clean energy, adapt our economies to make them digital, and develop more efficient transport methods. But again, the facts speak for themselves: China accounts for around 25% of all rare earth exports and around 60% of all lithium production, while Russia accounts for nearly 20% of all palladium and 11% of all nickel exports.

China’s control over lithium, renewables and electronics is extended by the fact that it controls a large proportion of the world’s mining, processing and production of these commodities through the businesses it owns – estimated at 63% of mining, 85% of processing and 92% of rare earth magnet production.10

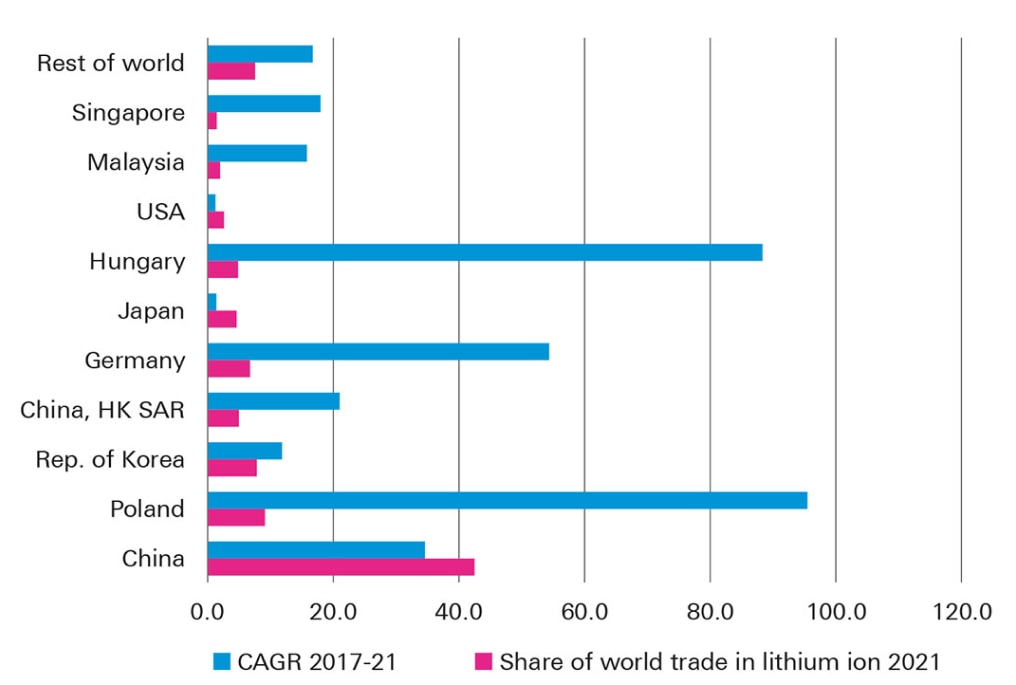

Just in terms of lithium ion, essential for battery production, China and Hong Kong between them account for nearly 50% of world trade (see Figure 3)

Figure 3: Top 10 lithium exporters – share of trade 2021 and growth rates (2017–21)%

Source: Comtrade and author calculations

There is rapid annualised growth in Germany, Hungary and Poland, suggesting that the EU is increasing its own self-sufficiency. Singapore and Malaysia also grew rapidly between 2017 and 2021. However, these rates of growth are from a much lower base than China, so there is little sign that Chinese dominance of global trade in the electric battery market faces imminent decline.

Vietnam’s emergence as a key REE exporter

There is a further challenge with rare earth elements (REE) that the US, the EU, the UK and the QUAD countries need to consider.11 Rare earth elements are not ‘rare’ as such, but are complex and environmentally hazardous to process. While REEs accelerate efficiency in fuel consumption, make vehicles lighter and more efficient, and improve the transformation of wind, light or water into electricity, they also require vast amounts of water and sulphuric acid to mine and process.12 REEs traded until recently at lower values in US dollar terms, and much of the resulting US$13m trade deficit in 2021 that the G7 had with the rest of the world could arguably be attributed to the more stringent environmental regulations that surround their mining and production processes.13

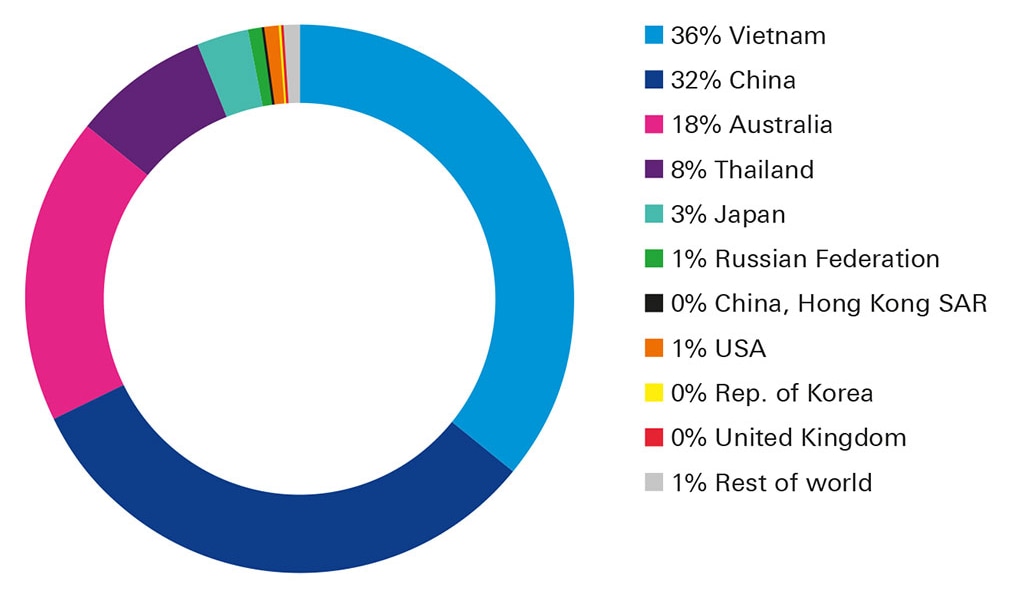

Along with China, Vietnam dominates the REE export market, and this is interesting from a supply chain resilience perspective (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: Share of world REE exports 2021

Source: Comtrade and author calculations

Vietnam is the world’s largest exporter of REEs in the form of ores – specifically monazite, xenotime and bastnaesite. These are used variously in renewables and construction: monazite is used in wind turbines, xenotime contains yttrium, which strengthens alloys and is used in radars and laser applications, while basnaesite contains cerium, which is used in magnets and high-tech communications. All three ores have multiple applications across the energy transition, net zero and supply chain resilience areas of national security.

As Figure 4 shows, Vietnam controlled approximately 36% of world REE exports in 2021. However, because the exports are as ore rather than refined products, this makes the country dependent on others for the processing of ore into rare earths that can be used in production. While it accounts for such a sizable proportion of exports, its production was barely 400 metric tonnes in 2021.14

At present, Australia is making significant investments in Vietnam for rare earth processing. Vietnam’s attractiveness has increased as the country and its allies have shifted to a “China Plus One” strategy. As a result of the China-Japan dispute over the Senkaku Islands, China suspended the supply of REE elements to Japan in 2010, causing prices to rise significantly.15 Japan also has a strong partnership with Vietnam for investment in REE production, but this has yet to yield high levels of processing. However, because Australia has strong expertise in mining and production already, there are synergies between the two countries that it is well-placed to develop.

A fresh perspective

The issue of supply chain resilience is one that will dominate trade policy for some time to come, especially as the issue has now become one of national security. “Resilience” means ensuring that supply chains are robust and continue to deliver energy, food and consumer products around the world. Increasingly, “resilience” also means the capacity to withstand climate shocks such as floods or tornados. Most importantly of all in the context of critical metals and REEs, it means delivering the capability to achieve net-zero goals by providing a bridge between a fossil-fuel based world and one based on renewable energies.

However, to do this, there are a few imponderables for the trade sector:

Trade fragmentation.

First, is there a way of reducing dependency on fossil fuels generally, and on Russia in particular, without increasing dependency on China? This is the essence of so-called ‘trade fragmentation’, which, according to the WTO and the IMF, is “now at the heart of the economic policy debate”.16 As the ICC articulates, it represents a “risk for business” because it alters the way in which supply chains are organised and business decisions are made.17 But what is it, why does it matter, and how can we bring the economics and politics of trade back together again in a way that supports supply chain resilience without, as the IMF’s Chief Economist Kristalina Georgieva says, “creating a world war”?18

Global infrastructures

Second, assuming that we can distribute supply chains, how are we going to build the infrastructure to make the transition effective? The global infrastructure is not built, and there is no clear agreement on who will pay for that development given current uncertainties around energy security and grid stability, geopolitics, and appropriate technologies, as batteries and hydrogen compete for dominance of the renewable future.

Cost of transition

Finally, perhaps the biggest imponderable of all centres around the price we are willing to pay to transition. It is here that there is a real paradox. We have already seen the impact of global inflation caused by energy shortages; prices will remain high while long-term strategies and investment are put in place to manage the transition. As a result, it seems that inflation will remain stubborn, as it is driven by transition infrastructure failures that are well outside of the domain of monetary policy. Similarly, the costs of transition include uncomfortable questions about mining and processing rare earth metals, given the environmental cost.

For the WTO, “trade continues to be a force for resilience in the global economy.”19 If this is genuinely to mean supply chain resilience as well, then there is a profound need to ponder the consequences of over-reliance on one country for the way we structure trade in the future, to address the funding of infrastructures that enable sustainable trade, and to accept that this will not be a cheap or easy process. These questions go to the very core of sustainable trade, and REEs and critical minerals are, as the name suggests, critical to this process.

Dr Rebecca Harding is an independent trade economist and a regular contributor to flow

Sources

1 See ft.com

2 See sap.com

3 See whitehouse.gov

4 See naturalresources.house.gov

5 See single-market-economy.ec.europa.eu

6 See gov.uk

7 See enseccoe.org

8 See state.gov

9 See economist.com

10 See brinknews.com

11 The Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, is a group of four countries: the US, Australia, India, and Japan

12 Guillaume Pitron (2020): “The Rare Metals War: The Dark Side of Clean Energy and Digital Technologies” Scribe London.

13 Guillaume Pitron (2020): “The Rare Metals War: The Dark Side of Clean Energy and Digital Technologies” Scribe London.

14 See thediplomat.com

15 See nytimes.com

16 See imf.org

17 See iccwbo.org

18 See theguardian.com

19 See wto.org