20 March 2024

Trade economist Rebecca Harding reflects on the fracturing of free trade and globalisation and what the ‘new normal’ of future proofing supply chains from geopolitics means for multilateralism as we know it

MINUTES min read

The World Trade Organisation’s (WTO) recent 13th Ministerial Conference in Abu Dhabi demonstrated the paradoxes that currently plague world trade: the opportunities of globalisation and free trade were emphasised but sat uneasily against a backdrop of the “fragmentation” of global trade since 2020, caused by the pandemic, supply chain shocks and geopolitical conflict. In my previous article, What are 2024’s trade megatrends I wrote, “The backdrop to international trade will be one of conflict,” This article provides additional insights into why this is happening and how war is reshaping trade.

Has trade changed for ever?

Frankly, expectations ahead of the conference were low, as was acknowledged by the WTO itself.1 The event itself showed that, despite best endeavours, bringing countries together around free trade is now tougher than ever. A new Realpolitik of world trade, as it has evolved post-pandemic, focuses as much on national interests as it does on multilateralism. and The WTO’s dilemma is that it sees interdependence through trade as a force for “peace, prosperity, higher living standards and poverty reduction” on the one hand, while on the other it is keenly aware of the fact that trade is increasingly prone to geopolitical tensions and fragmentation in an era of “polycrisis”.2

So, what is going on in international trade? Has trade really changed and, if so, are there still opportunities around which we can all agree?

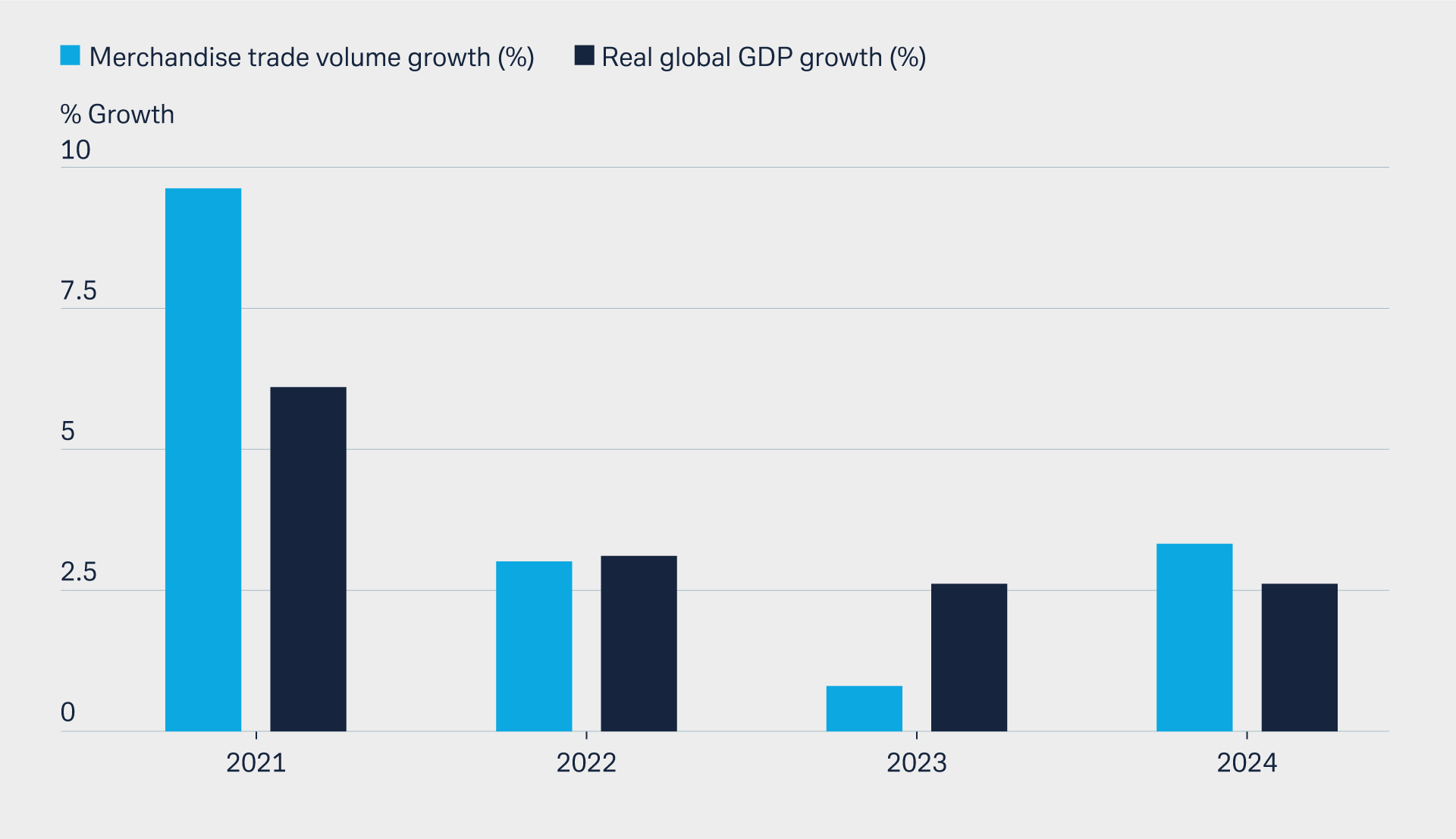

Let us start by understanding why global trade appears to be so much under pressure. The WTO’s most recent Trade Outlook issued last October had forecast slower global merchandise trade growth in 2023.3 The downward revision suggested that goods trade volumes grew by just 0.8% during the course of the year against the earlier forecast of 1.7% it issued in April (see Figure 1).

In the two decades post globalisation it was assumed that trade would grow at roughly twice the rate of global GDP growth.4 This justified the assumption of the WTO that trade would always be a driver of positive and inclusive growth, especially in emerging economies. But with trade expected to grow at just 3.3% in 2024 - a similar level to the IMF’s projected GDP growth of 3.1% this year – this assumption is now called into question.5 Perhaps trade is not playing the same role in the world economy that it once did.

Figure 1: Merchandise trade and GDP growth estimates (2021–2023)

Source: World Trade Organisation, Trade Outlook 2023

NOTE: 2023 and 2024 are projections

However, one must be careful with this type of interpretation. There are two specific reasons why. The first is a simple, statistical point. We are not historically comparing like with like and, taking this into account, may well be looking at a reduction in the levels of merchandise trade. These days, we measure service sector trade in international statistics to a far greater extent than was the case prior to the 2007–09 Global Financial Crisis.

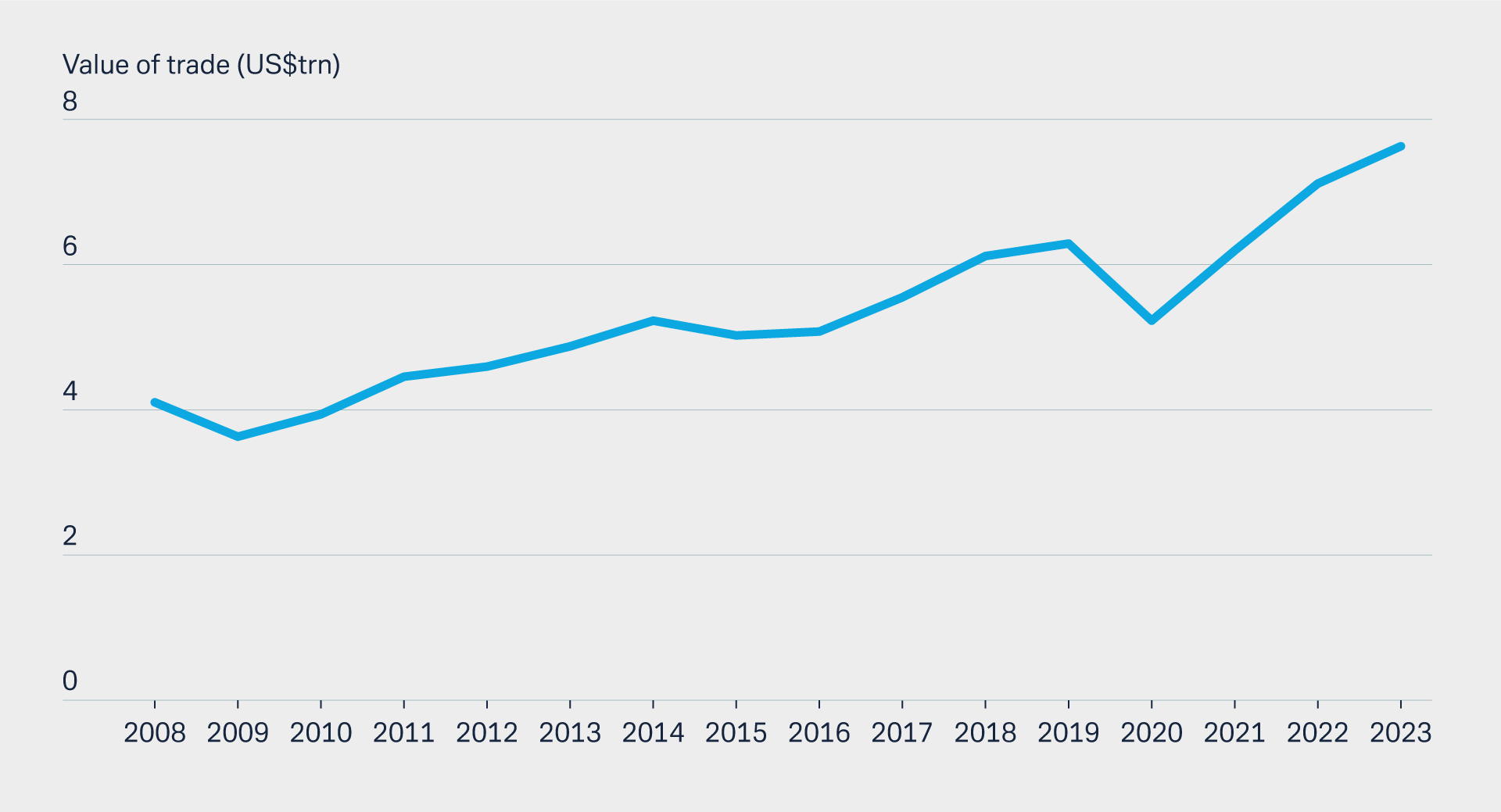

While merchandise trade fell in the first half of 2023 from H1 2022, commercial services trade grew by 9% year-on-year. Admittedly service trade grew globally by 15% in 2022 according to UNCTAD, but the point nevertheless is that not all trade is performing in the same way. The trade we should be including in our aggregate measurements now is materially different to that measured two decades ago because it includes services, which have doubled in value terms globally since 2008 (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Value of world services trade, 2008–2023 (US$trn)

Source: UNCTAD, 20236

NOTE: 2023 is a projection

The second reason for caution is that we have experienced a period of significant geopolitical, geoeconomic, technological and climate disruption in the past five years. Each of these factors has its own origins and its own individual impact on trade. Collectively, they impact the way in which we trade and the way in which we finance trade through supply chains. Throughout the era of globalisation, it was these supply chains that created the inter-dependencies intrinsic to international trade. It is how we operate and manage them that is both the core change and challenge that we now face.

“The increase in services trade is emblematic of the very nature of globalisation and inter-dependency”

World trade is itself materially different – service trade has doubled in value terms since 2008 and now constitutes 23% of total trade on average across the world. Arguably the increase in services trade is emblematic of the very nature of globalisation and inter-dependency: services are the cross-border movement of capital, people, ideas, intellectual property and technologies. Merchandise trade depends on finance, laws and regulations, business services, servicing, shipping, wholesale and retail – these are all services and integrally interwoven with supply chains.

Supply chains – globalisation’s Achilles Heel?

Now it is clear that supply chains are the vector through which disruptions to trade now operate, 2024 brings five key challenges:

- Sanctions and export control regimes;

- The current conflict in the Middle East and its escalation into the Red Sea;;

- Ongoing impact of geopolitics;

- 2024 is a year of elections in many key economies; and

- The China factor.

1) Sanctions and export control regimes

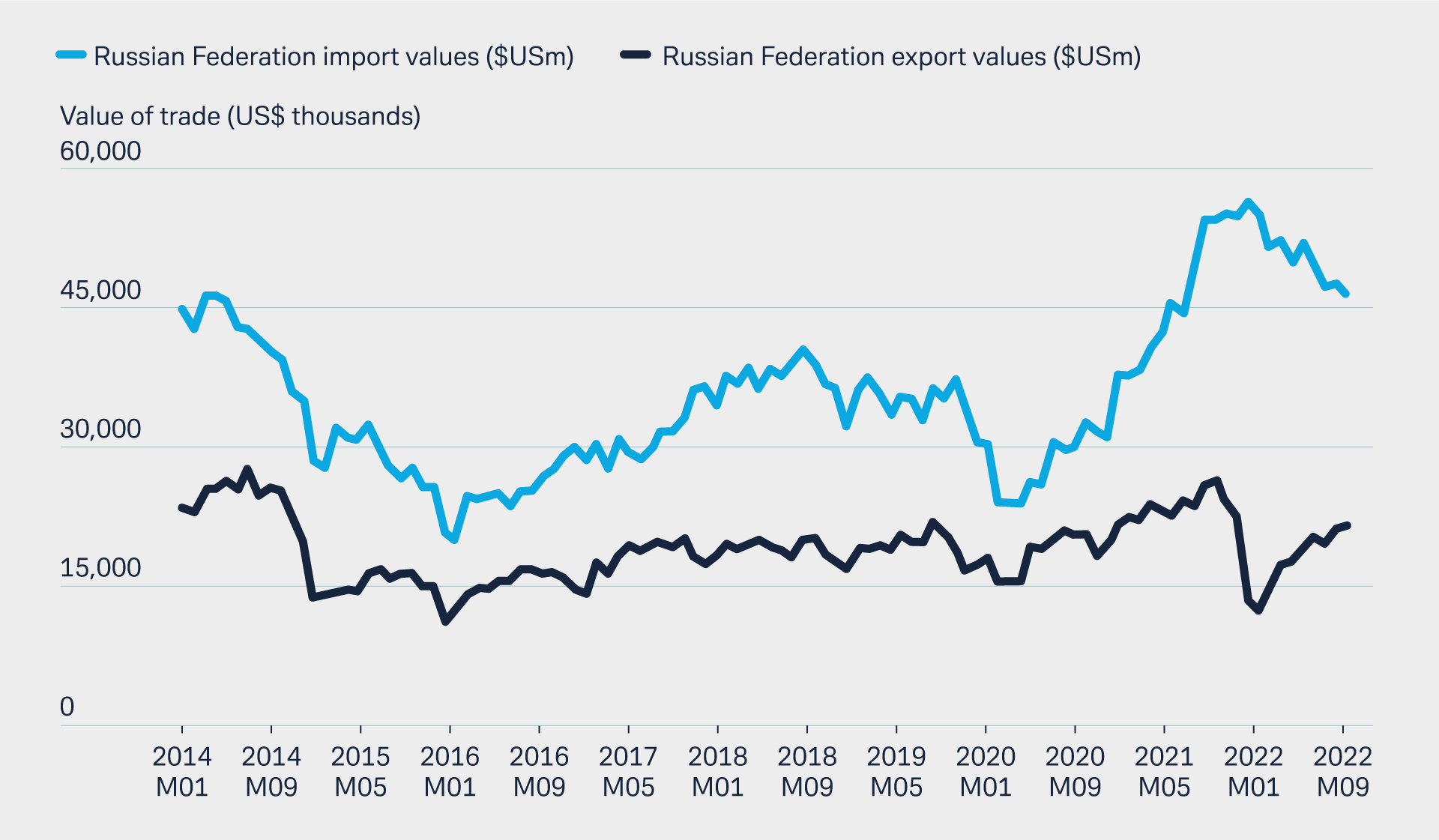

The sanctions and export control regimes put in place since the start of the Russia-Ukraine crisis in February 2022 will continue to disrupt energy supply chains and business supply chains more generally. For example, these sanctions have reduced Europe’s dependency on Russian energy supplies but have not actually had an enduring impact on Russia’s trade volumes (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Russia’s exports and imports, January 2024–December 2022 (US$m)

Source: IMF Direction of Trade Statistics, November 2023

Note house style is US$m

There is an evident uptick in Russian exports from May 2022 that has continued through third countries, such as India, China, and Turkey. What this tells us, quite apart from any geopolitical story, is that energy supply chains have been diverted. For example, millions of barrels of oil that originated in Russia come into the UK via India in a way that is not illegal but which highlights “rules of origin” loopholes.7

This is an illustrative point but serves to highlight the complexities in supply chains and supply chain finance that are now the reality of daily trade operations. The scope of financial crime now includes complex lists of sanctioned individuals and entities alongside products in supply chains themselves that may be categorised as “dual use” or may contain technologies that are directly prohibited as they are military grade.

These complications are compounded by something called “parallel trade”: where a component is supplied without a copyright holder’s permission. In other words, when a product, such as a washing machine, contains a military grade semi-conductor, it goes over the border as a washing machine and not as military grade technology. Unwittingly, a country or a supplier may be exporting a prohibited item legally but with the effect of allowing a sanctions regime to be circumvented.8

This does not affect trade with Russia. The US and EU putative “Chip Acts” incentivise EU or US manufactured semiconductors9 and place investment and tax differentials between the two blocs in the middle of supply chain competitiveness. Similarly, US restrictions on the use of its technology in Chinese military applications serves to complicate supply chains further.10

The net effect is, arguably, to “weaponise” the interdependencies that are intrinsic to supply chains, indeed to globalisation itself. It means that corporates, and their trade finance providers, must engage on a more detailed and sophisticated basis throughout their supply chains to identify where they might fall foul of sanctions or export control regimes, or indeed be able to take advantage of investment incentives. This represents a long-term shift in the way in which trade finance professionals will have to work with each other in 2024 and beyond.

2) Conflict in the Middle East and Red Sea

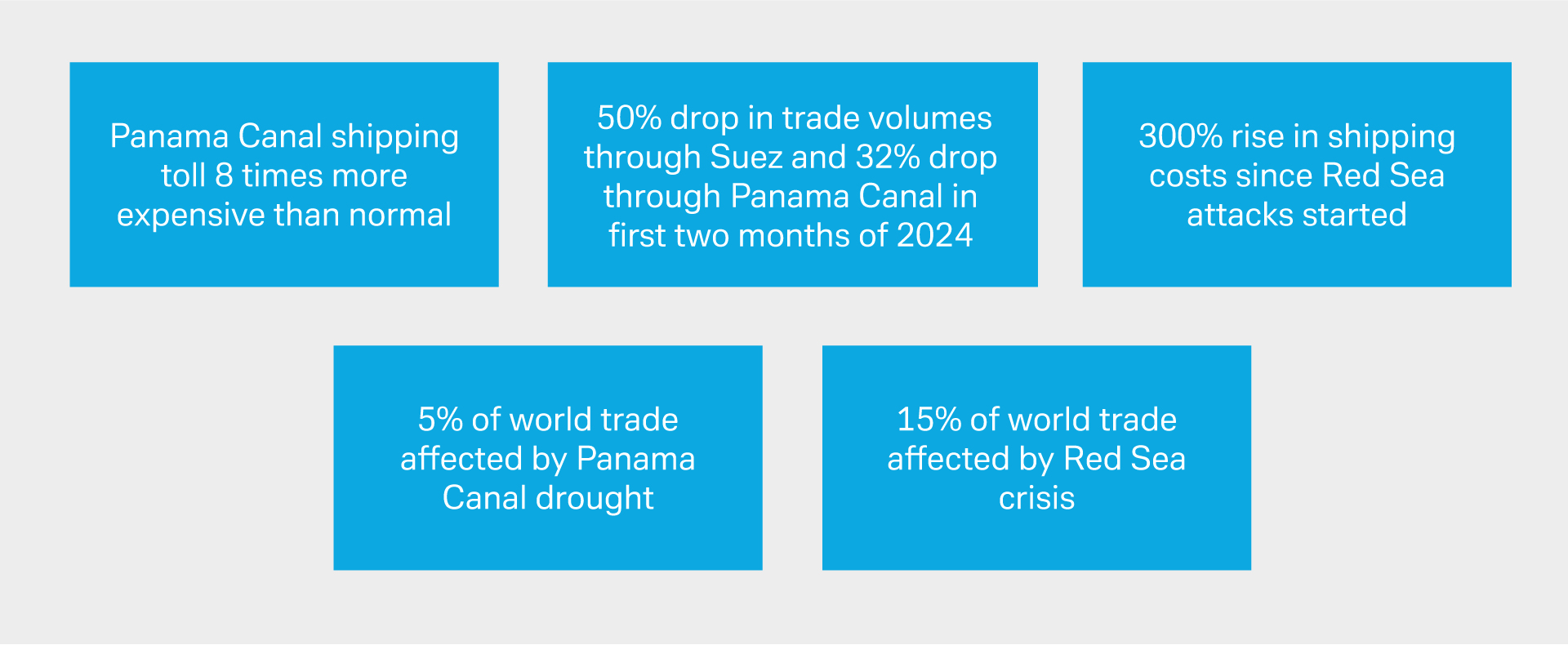

There is a direct impact on supply chains caused by the current conflict in the Middle East and its escalation into the Red Sea. Alongside the drought in the Panama Canal, the disruption to trade, and therefore supply chains, potentially affects some 20% of world trade by increasing costs and journey times (Figure 4); a point made at the BAFT European Bank to Bank Forum in Frankfurt by a panel reviewing the main trade pinchpoints (January 2024).

These underline the vulnerability of global trade to supply chain disruptions that could push up prices relatively quickly. The Red Sea situation is deteriorating, and warnings are being issued by shipping analysts that this is already a bigger supply chain disruption than that experienced during the pandemic.11

Figure 4: Direct supply chain crises at the beginning of 2024

Sources: Sky News,12 Wall Street Journal,13 IMF14

3) Ongoing impact of geopolitics

There is no reason to suppose that geopolitics will reduce in impact during 2024. The Russia-Ukraine crisis is now in its third year, and while the initial inflationary consequences of reducing European dependency on Russian oil, gas and grain may have abated somewhat, the UK’s energy prices remain nearly 60% above their 2021 levels.15 Geopolitics has the potential to affect oil prices, which have risen this year already as a result of the Houthi attacks and the conflict between Israel and Hamas. Although they remain below the levels seen after Russia invaded Ukraine,16 this underlines the inflationary pressures in the global economy.

4) 2024 – a year of elections

Fourth, the impact of so many elections in 2024 cannot be understated. More than half the world’s population will vote during the course of this year. The hidden impact of this electoral activity is the inevitable policy inertia for all practical purposes as political parties vie to gain or retain power. In the UK, there is talk of tax cuts that might come as a result of this process, but any tax reductions could well be push up inflation over a longer period of time for the simple reason that there is more money in the economy chasing goods in short supply. Structural economic challenges, like infrastructure investment, trade policy or measures to deal with climate change, will be left until after the general, or in the case of the US, Presidential election.

5) The China factor

Finally, there is China, whose economy is growing more quickly than any of the G7 economies but is sluggish compared to its pre-pandemic levels, creating a dampening effect on global economic growth. Its geoeconomic role affects access to semiconductors and rare earth metals that are critical to our transition to lower carbon business models. China dominates two-thirds of electric vehicle production17 so it has a large amount of power to push up prices, putting more inflationary pressures on both consumers and businesses as they attempt to move towards net zero targets. This dominant role in critical supply chains is unlikely to diminish in the near term, and while tensions appear to have dialled down a little recently, there is broad bipartisan support in the US for a tough approach to China.

Multilateralism and the “New Normal”

Geopolitics, geoeconomics and the fragility of the world as it undergoes a period of disruption present opportunities as well as risks. Uncertainty and change are endemic, however. Trade finance providers and their corporate clients are working together to understand deep-tier supply chains, not just in terms of their risks, but also in terms of improving sustainability and of making them function more efficiently through digital trade. These are opportunities that will develop during the course of this year.

It is always sensible to be wary of the politics behind all of this, however. The tensions ahead of the WTO’s Ministerial Conference are arguably a product of the greater influence that the BRICS countries of Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa have on global trade and their role in defining the “new normal” of trade as we move towards greater digitisation, supply chain de-risking and a stronger focus on sustainable trade during the coming year. One should remember that these are multilateral challenges, and ones on which the maintenance of the international rules-based order that the WTO represents depends.

Corporates and banks know the importance of change and uncertainty management. Perhaps, in 2024 this offers the most scope for businesses, corporates and finance to work together so that trade infrastructures can adapt to the challenges that the “new normal” will create.

Sources

1 See wto.org

2 See wto.org

3 See wto.org

4 See imf.org

5 See imf.org

6 See hbs.unctad.org

7 See bbc.com

8 See thediplomat.com

9 See brookings.edu

10 See foreignpolicy.com

11 See cnbc.com

12 See news.sky.com

13 See wsj.com

14 See imf.org

15 See commonslibrary.parliament.uk

16 See bbc.com

17 See axios.com