10 June 2024

While important progress is being made worldwide on financial inclusion, de-risking may act as a brake on that progress. Joy Macknight explores what can be done to address banks terminating or restricting activities with clients

MINUTES min read

Financial inclusion is a key enabler to reduce extreme poverty and boost shared prosperity, and contributes to seven of the 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).1 Having access to useful, reliable and affordable products and services is vital for all types of customers, from micro, small and medium-sized enterprises through to large corporates and financial institutions.

For the latter, correspondent banking services, such as cross-border payments and trade finance, allow them to participate in the global economy. In addition, individuals, small businesses and charities also require access to cross-border cash services to send remittances to their home country, pay bills and salaries, and purchase goods.

“Whether it is supporting large infrastructure projects or facilitating aid flows to distressed areas, providing financial services dramatically impacts people’s livelihoods and their ability to survive, as well as driving economic growth and a country’s ability to attract investment,” says Patricia Sullivan, Deutsche Bank’s Global Head of Institutional Cash Management.

The threat of de-risking

Significant progress has been made in access to and usage of financial services over the past decade. For example, 76% of adults today have access to a bank account globally, a 50% increase compared to 2011, according to the Global Findex 2021 report.2 As Marion Laboure, Deutsche Bank Research Senior Strategist, points out in her book, Democratizing Finance: The Radical Promise of Fintech, digital technology has improved financial inclusion.3

“Consider the basic benefits of having a bank account: it allows individuals to save, earn interest, balance household consumption and raise productive investment. Moreover, a bank account can empower women and give them more economic equality,” Laboure explained. Thus, she recommends developing countries to launch programmes to digitise IDs, invest in telecoms and payment infrastructure for rural areas and make use of fintech ecosystems.

However, de-risking – which is defined as financial institutions’ terminating or restricting activities with clients or categories of clients to avoid risk – is a countervailing trend that threatens to increase financial exclusion. De-risking can happen at the individual or business level, but also at the financial institution or country level, where correspondent banks have pulled out of countries deemed too risky – or too costly – from a financial crime or compliance perspective.

The growth in financial crime, such as money laundering, terrorist financing, corruption and bribery, and the regulatory response of increased supervision and significant fines, has led to an intensification in de-risking over the past two decades. Geopolitical conflicts, such as the Russia-Ukraine war, have also contributed as banks are faced with implementing a growing number of sanctions across multiple jurisdictions and are also liable for secondary sanctions.4

“The financial sector has become even more conservative in its risk appetite in light of the potential for severe penalties in a rules-based regulatory environment,” says Sullivan. “Therefore, it becomes easier to cut some of the clients or countries with high-risk indicia than to potentially withstand that scrutiny.”

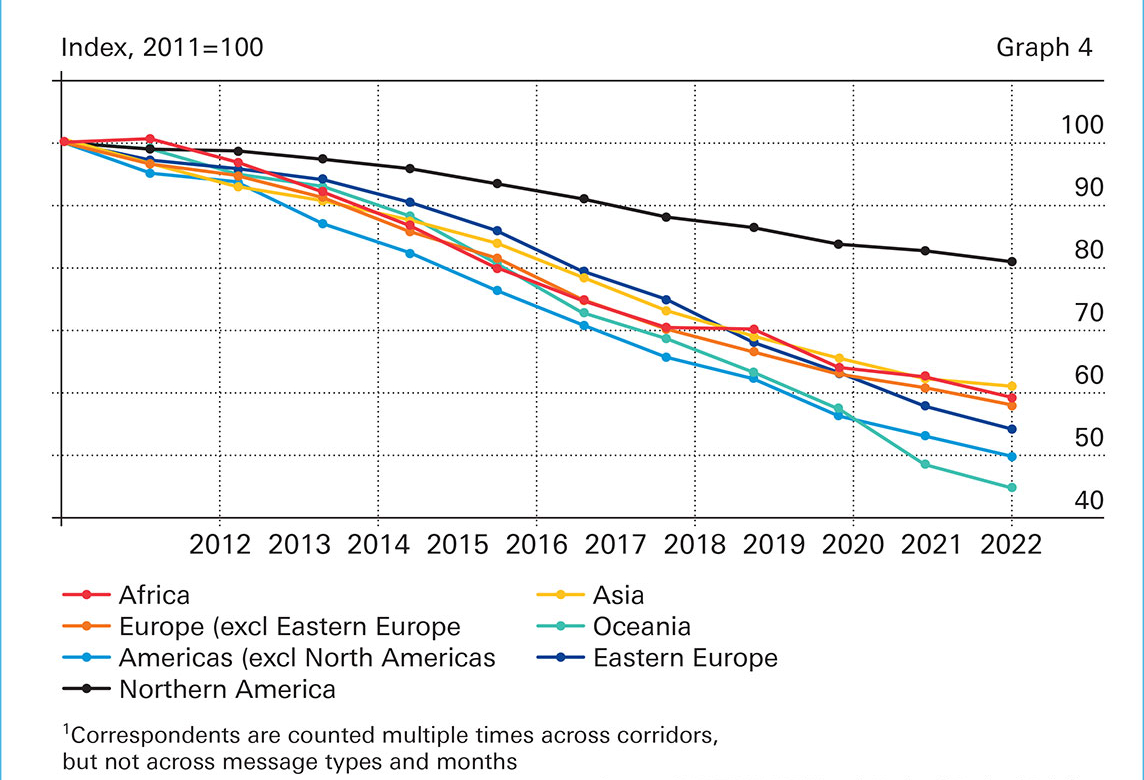

Some regions have been hit harder than others, with many correspondent banks withdrawing from high-risk jurisdictions. For example, according to Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures (CPMI) data, Melanesia, Polynesia and the Caribbean have seen the biggest drops in the number of correspondent banking relationships between 2011 and 2022: 62.6%, 54.0% and 52.1%, respectively. Likewise, the number of banks providing US dollar clearing services has declined from 100 providers in 2006 to around 60 in 2022.5

Figure 1: Number of active USD correspondents by region (count of counterparties abroad)1

Source: SWIFTBI WATCH and National Bank of Belgium

Intense scrutiny

Regulators are actively working to stem de-risking to promote financial inclusion and systemic stability. For example, the European Banking Authority (EBA) released its report on tackling unwarranted de-risking in January 20226; and in April 2023, the US Department of the Treasury launched its de-risking strategy.7

According to the EBA, while de-risking can be a legitimate risk management tool, “it can also be a sign of ineffective money laundering and terrorist financing risk management, with at times severe consequences.” It has committed to following-up with competent authorities on the actions they are taking to tackle unwarranted de-risking.

Sullivan believes that the first step in addressing de-risking is for regulators to implement risk-based supervision, rather than taking a rules-based approach. “For example, introducing a rule that all charities must be rated high risk can lead to de-risking because a bank must deploy more resources to manage that relationship. However, the charity may not provide sufficient revenue for the bank to justify that increased cost,” she explains. “And, in fairness, not all charities are high risk.”

The Financial Action Task Force (FATF) recommendations8 for combatting money laundering and terrorist financing calls for risk-based supervision, but Sullivan believes there’s still some way to go, including in so-called ‘developed’ countries. Significantly, both the EBA and US Treasury have highlighted the importance of taking a risk-based approach in their recent guidelines.

“A black-and-white approach to risk management is not helpful”

Sullivan stresses that taking a risk-based approach is not inconsistent with developing a strong financial crime risk management framework, but allows banks to have flexibility when assessing and managing risk.

“This also applies at a country level. It is possible to have strong financial institutions that are present in a country with high inherent risk for money laundering, bribery, sanctions, etc,” she says. “Banks need to perform assessments, understand the risk and control it adequately, taking more of a black-and-white approach is not helpful.”

The true cost

Many banks have gone down the de-risking route because of the increased cost associated with providing services in a heightened risk environment. However, if banks are pulling back because they cannot effectively manage risk, then they are effectively shifting the problem from one bank to another. Such a move can also compel individuals and businesses to use channels that are not as safe or secure, as well as much more expensive.

“What isn’t included in the individual bank’s financial equation is the socio-economic impact that de-risking has, the risk inherent in moving to another provider and the stability and protection of the financial system, which is the regulators’ ultimate aim,” says Matthew Probershteyn, Head of ICM Non-Financial Risk and Controls, Deutsche Bank.

Probershteyn highlights the inverse correlation between de-risking and transparency in risk management, particularly in jurisdictions lacking the infrastructure or resources to support transparency in financial services. He argues that pulling out of those geographies will amplify the problem, instead of solving it.

“When a correspondent bank is providing products and services to a country, it is also promoting best practice in risk management and the regulatory landscape,” he explains. “The unintended consequence of de-risking is that it will impact a country’s ability to enable law enforcement, and for example to develop the anti-bribery or anti-corruption environment that would have been there if the bank was present and fighting that fight. This will impact generations to come, yet it remains unseen and unmeasured.”

Creating a new framework for risk management

Therefore, partnering with a customer or country to ensure high standards is an important part of financial inclusion. Commercial banks such as Deutsche Bank have a critical role to play, according to Probershteyn. “We can provide our experience as to what good looks like and how to put in place the right guiderails to improve,” he explains.

For example, at a macro level, Deutsche Bank can support clients with on-the-ground guidance in countries where work is required to address FATF recommendations and where support is needed to attain SDGs.

Sullivan uses the example of a country where a bank is the last foreign bank providing access to US dollar clearing services. “It isn’t just about enabling cross-border access for this country. The bank will also very likely work closely with the government to provide thought leadership on other issues such as sustainability,” says Sullivan.

Deutsche Bank has been investing in its partnership programmes, creating a framework to support financial institution clients in challenging markets. “If they have issues with their risk management programme, we can provide recommendations to help collectively manage down that risk and improve the programme,” says Probershteyn.

The framework includes:

- Educating clients in know-your-customer (KYC) and transaction-monitoring strategies to identify shell companies

- Advising clients on sanctions evasion risks presented by commodity traders /brokers

- Sharing best practices on transaction monitoring, adverse media screening and filtering new technologies

- Sharing latest geopolitical trends and hotspots where enhanced due diligence may be required

- Informing on new client risk rating methodology and risk assessment approaches Deutsche Bank is deploying

The bank now regularly hosts seminars relating to sanctions evasion risk for financial institution clients, most recently in Spain and Italy. “Via our de-risking through partnering and education approach, we work with clients to address these issues, including conducting onsite visits to bring residual risk within the parameters of our risk appetite,” adds Sullivan.

Probershteyn emphasises the collective role all constituents in the ecosystem has to play to curb the de-risking trend and enhance the fight against financial crime from central and commercial banks to law enforcement, regulators and clients. “For example, central banks need to act if there is an indication that commercial banks are pulling out due to changes in the risk environment. That includes investment at the central bank level to ensure that their controls and regulations are there to promote open and transparent banking,” he says.

Joy Macknight is a freelance financial journalist and former editor at The Banker, part of the Financial Times group

Sources

1 See sdgs.un.org

2 See worldbank.org

3 See Democratising finance

4 See spglobal.com

5 See bis.org

6 See eba.europa.eu

7 See home.treasury.gov

8 See fatf-gafi.org