16 November 2023

What are the differences between stablecoins, tokenised deposits and deposit tokens? Which projects are the most relevant to follow and why? Deutsche Bank’s Manuel Klein shares his thoughts with Kate Pohl, consultant for the Euro Banking Association

MINUTES min read

Central banks as well as the private sector are expanding the portfolio of digital money in the monetary system. On 17 October 2023, Manuel Klein, Product Manager Blockchain Solutions and Digital Currencies, Deutsche Bank spoke about the latest developments in this field at the Open Forum on Digital Transformation hosted by the Euro Banking Association (EBA). Kate Pohl, consultant, moderator, and facilitator for EBA, shares his insights for flow in a two-part summary.

While Part 1, ‘CBDCs in Europe: retail and wholesale projects to follow’ set out the most recent developments on Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs) in Europe, Part 2 (this article) examines relevant projects around blockchain-based money from the private sector.

Stablecoins – relevant projects to follow

As a reminder, commercial bank money and electronic money, which is issued by e-money licensed institutions such as PayPal under the e-money directive1, are liabilities of private entities and already exist today. These funds can be held by retail or wholesale clients as bank deposits or balances in a digital e-money wallet. Tokenised deposits at banks or tokenised e-money (the regulated form of stablecoin in the EU) are new forms of digital ‘private money’ using blockchain technology.

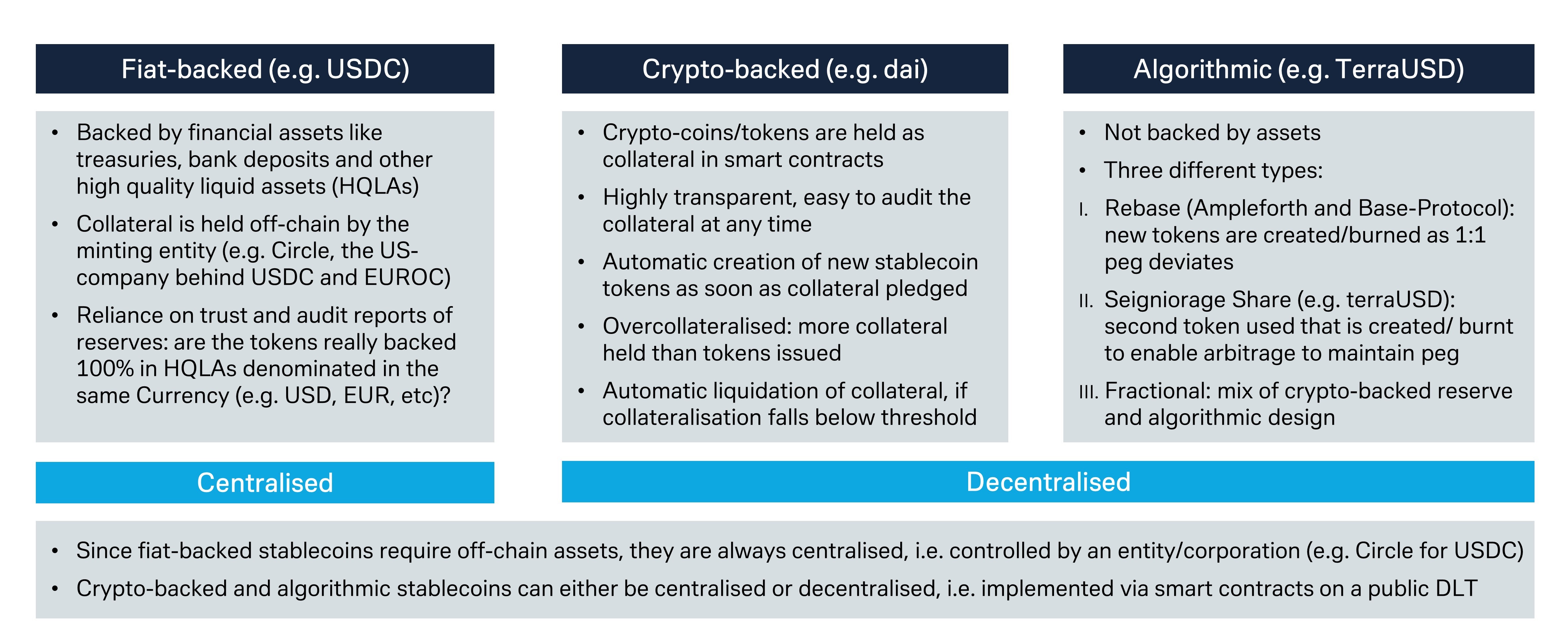

There are different types of stablecoins, including the popular fiat currency-backed stablecoins (see Figure 1). Examples of the latter are those issued by centralised institutions such as Circle (the USDC stablecoin) or Tether (the USDT stablecoin). These tokens are backed by eligible assets held at certified custodians. Collateral may take the form of bank deposits or securities e.g., short term government bonds. “In essence, a closed loop environment encompassing the issuers is created. This sits ‘on top of’ bank deposits and existing securities allowing for efficient settlement,” explained Klein.

Centralised, fiat-backed stablecoins, such as USDCs, are a private digital form of money regulated in Europe since June 2023 by the Markets in Crypto-Assets Regulation (MiCAR).2 The MiCAR builds on already established national electronic money directives of each European nation but now provides a European regulation for all crypto-services and issuers of stablecoins.

There are also stablecoins backed by other crypto coins and tokens which rely on an over-collateralisation to keep a stable value against e.g., the USD. Automatic liquidation is possible/allowed if the over-collateralisation of these tokens falls below a defined threshold. The stablecoin ‘Dai’ is an example of this type of stablecoin.

There are also algorithmic stablecoins, which do not have any assets backing them at all. The best-known example is ‘Terra’, which collapsed in May 2022.3 In the wake of Terra’s collapse, many other players, providing services in the crypto sector, went bankrupt over the last one and a half years. “Algorithmic stablecoins,” noted Klein, “are based on algorithms that are meant to stabilise the value based on a fluctuating supply and demand for the token. However, to date, all prominent algorithmic stablecoins have ultimately failed to hold their peg to the US dollar. The collapse of the Terra-ecosystem - around the TerraUSD stablecoin - has led to sector-wide bankruptcies in the 'centralised finance' crypto industry which is focused on lending and borrowing crypto currencies,” said Klein.

Figure 1: Different types of stablecoins

Source: Deutsche Bank

Tokenised deposits and deposit tokens

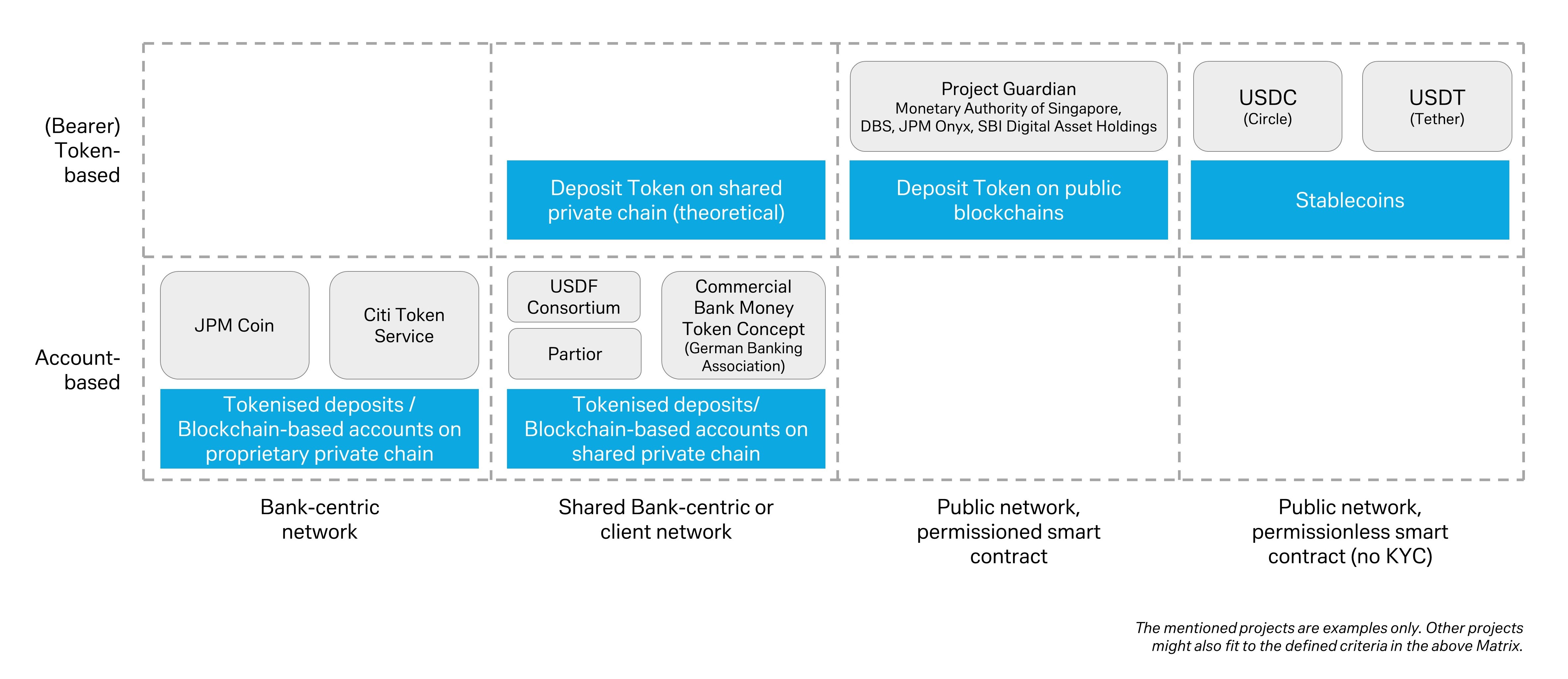

Various banks such as J. P. Morgan4 and most recently Citi5, have also started to issue a blockchain-based version of money which a client can hold in their bank account. These deposits can also be moved on the bank’s blockchain between clients. What is missing for scale, however, is settlement between different tokenised deposit solutions of multiple banks. Today financial institutions settle in central bank money via so called ‘real-time gross settlement systems’ (RTGSs). The blockchains of banks would need to be connected to these platforms or to a blockchain-based version of central bank money, a so-called ‘wholesale CBDC’ issued as a token on a blockchain.

The ‘trigger solutions’ from the Bundesbank or the Bank of Italy, or the wholesale CBDC token of the Banque de France – as described in Part 1: ‘CBDCs in Europe: retail and wholesale projects to follow’ – could be used to enable settlement between different tokenised deposit solutions of multiple banks. If such systems weren’t available, bilateral nostro accounts could be maintained by the different participants. This would allow the clearing of transactions to take place between the clients of the banks involved. “On a comprehensive scale, however, maintaining a large network of bilateral nostro accounts would neither be efficient nor cost effective. Hence, connection to a settlement system is needed,” said Klein.

“What still remains unanswered is the question, as to whether or not the issuer of such a deposit token would need to keep records of ownership of bearer deposit tokens in their internal systems”

To overcome these hurdles, some banks have started to investigate the issuance of bearer-like tokens that anyone can hold. This would include citizens or corporations that are not clients of the issuing bank. ‘Deposit tokens’ could support settlement – based on the liabilities of an issuing bank – without the need to settle in central bank money. “What still remains unanswered is the question, as to whether or not the issuer of such a bearer deposit token would need to keep ownership records in their internal systems,” Klein noted. “It is likely to be the case that an issuing bank will need to know who is holding their tokens and only identified, onboarded and KYCed individuals or entities will be able to hold such instruments.”

Differences between stablecoins, tokenised deposits and deposit tokens

Issuers of stablecoins, that can be found on public blockchains, may ‘blacklist’ certain addresses. This restricts the corresponding wallets from holding or using the relevant instrument. Circle, for example, is not concerned with the question of who holds their tokens,6 except for blacklisted addresses.

This is very different to the way in which banks manage client deposits. The holder of an account is always ‘onboarded’ and ‘known’ to the bank. Rather than rejecting certain parties through blacklisting, banks may use a whitelist approach for their deposit tokens, instead. This would mean only allowing addresses that have gone through a KYC process to hold tokens, instead of making them available to anyone and only later restricting ownership of a few addresses.

In addition to issuing account-based or bearer-based money on individual, bank-centric blockchains, some financial institutions are also working in groups towards a shared ledger approach. The idea is to issue and move money on a ledger that is used by multiple banks, either as a shared private blockchain or even a public blockchain.

The BIS, the Bank for international Settlements (the central bank of the central banks), is doing lots of research on digital money from both commercial and central banks. “They are looking at distributed and programmable infrastructure, with the goal of issuing tokenised deposits from different banks and central bank money on a ‘unified programmable ledger.’ These tokenised deposits would settle in central bank money e.g., a token-based wholesale CBDC.7 This bank-permissioned infrastructure, which is still in concept-mode, would be very similar to the concept of the regulated liability network that was already tested in two proof of concepts in the UK and the USA,” explained Klein.

Klein also noted that “other consortia are building solutions without including central bank money in their network for settlement. These projects include a variety of possibilities for example, bilateral bank nostro accounts or using ‘trigger solutions’ into existing (central bank) payment systems (e.g., Partior, USDF or the concept of commercial bank money tokens from German banks and industry partners) or prefunded tokens that represent central bank money held in an omnibus account at central banks (Fnality).”

There are also banking groups working on proof of concepts (PoCs) and pilots for deposit tokens issued on a public network using a ‘permissioned’ smart contract. The best-known example is project Guardian, sponsored by the Singaporean central bank, that tested the issuance of a bearer-like token that represented deposits of the issuers.8 Permissioned means that only those who go through a KYC process and are whitelisted – and therefore eligible – can hold the token. In this project, digital identities were issued as tokens for the wallets of verified users i.e., ‘verifiable credentials’. The KYC process was shared between the participating financial institutions acting as ‘trust anchors.’ Having agreed on processes and standards, mutual trust was established among the banks. This allowed the settlement of tokens across the boundaries of the respective bank balance sheets between all participants that might not be clients of the issuers of the token.

Stablecoins also fit into this matrix as they are issued as bearer-like tokens on public blockchains by using ‘permissionless’ smart contracts. Here, any wallet or smart contract may engage, and the issuer does not need to do a KYC check on the token’s holder. Anyone with an appropriate, compatible wallet that supports the token standard e.g., an ERC-20 standard on Ethereum, can hold the liability of the issuer and hence the tokenized form of money.

Figure 2: Difference between tokenised deposits, deposit tokens and stablecoins

Source: Deutsche Bank

Looking ahead

The complexity surrounding digital money is significant. This is coupled with a great deal of uncertainty regarding the timing, regulation and adoption of new technologies relating to different forms of money. While the ECB has agreed to continue the digital Euro project in a next ‘preparation phase’, it has not yet decided whether or not to actually issue the digital Euro and therefore a retail CBDC. Decisions will only be made after the two-year preparation phase i.e., not until the end of 2025.

Many unanswered questions remain with regard to the new and different forms of both public and private digital money. Will stablecoins, under the new MiCA regulation, become a major form of digital money? Will banks need to rely on settlement of their tokenised deposits through central bank money or will bearer-like forms of deposits from each bank emerge? And will the market convince the Eurosystem that blockchain technology provides real added value for wholesale CBDC?

The above points are just some of the issues to consider as stablecoins evolve. There is significant innovation going on in the market and for this reason, a good understanding of both the enormous potential as well as the consequences of different end positions is important for all participants in this brave new world of digital money.

Sources

1 See ecb.europa.eu

2 See esma.europa.eu

3 See forbes.com

4 See ledgerinsights.com

5 See citigroup.com

6 See theblock.co

7 See bis.org

8 See mas.gov.sg