September 2020

On 11 March 2020 the World Health Organization declared Covid-19 a global pandemic. Six months on, different regions are at different stages of their response to the crisis. This article examines its developing impact on households, businesses and governments, drawing on in-depth research by Deutsche Bank

Deutsche Bank Research notes that global economic activity has picked up faster than was initially envisaged

Early hopes that the pandemic would be short-lived, to enable a V-shaped economic recovery, quickly gave way to a recognition that its impact could persist for much longer. Despite this, pessimistic forecasts issued in the spring have since been tempered to a degree. In its World Outlook: Interim Update and Longer-Term Projections of 5 August, Deutsche Bank Research noted that global economic activity has picked up faster than was initially envisaged. The Research team’s projection in May that 2020 global economic activity would decline by nearly 6% was revised to 4.5%.

For 2021, Deutsche Bank Research expects a bounce back to 5.5% growth, but thereafter the prognosis is for the rate to slow, as unemployment moves back to pre-pandemic norms by 2024–2025. Overall, the team expects “trend or potential growth rates to be somewhat below pre-virus rates” due to several factors that include:

- Ageing populations and slowing labour force growth as baby boomers continue to retire;

- Fiscal drags as taxes are raised to begin to pay for the fiscal support necessitated by the pandemic;

- The virus causing lasting disruptions to activity in some sectors; and

- Likely ongoing disruptions caused by tensions in US–China trade and investment relations, together with the reorientation of global supply chains.

As many reports have noted, the pandemic’s impact varies from country to country. China, where cases of Covid-19 were first reported, instigated an early lockdown and its policy was adopted by others such as South Korea and New Zealand, which subsequently eased restrictions while watching for local flare-ups. Elsewhere, particularly in the US and Brazil, governments either lifted lockdowns too quickly or never activated them nationally, and saw figures for new cases rise steeply.

Relative successes

To the possible chagrin of some, Asia “continues to offer the most positive examples of how to suppress the Covid-19 virus and, having done so, of how quickly economic activity can recover,” suggest Deutsche Bank Research’s chief economists. In their Asia Macro Insight note of 14 July they cite China, Hong Kong, South Korea and Vietnam as the region’s most successful, as measured by containment and subsequent strong recoveries in consumption. Others, whose lockdowns proved less effective, will see a commensurately weaker rebound. Assuming that the worst of the crisis is behind them, policymakers are expected to transition from providing emergency support to their economies to monitoring the recovery and gradually scaling back stimulus to avoid a ‘fiscal cliff’ drag on growth as emergency measures are removed.

For economies with stronger recoveries and acceleration in asset price inflation – principally China and South Korea – the question increasingly is when do they begin normalising rates? The Research team expects the process to begin in 2021, long before the Federal Reserve or the European Central Bank adopt such measures.

Meanwhile, the International Monetary Fund now forecasts that China will still achieve growth – albeit only by 1.2% – in 2020, and then exceeding 5% in the subsequent five years to comfortably exceed any other major economy.

Eurozone adjustments

In the eurozone, analysts have adjusted their projections for recovery after the economic contraction caused by lockdown proved less severe than was earlier predicted. In its 11 August forecast update, Euro Area Growth Better in 2020, a Little Worse in 2021, the Deutsche Bank Research team reports that while Q2 2020 saw a record rate of contraction, the GDP outcome “reflected a less deep lockdown trough and a more rapid post-lockdown bounce”, to be more fully reflected in Q3 data. The team predicts a slightly slower pace of normalisation in 2021 and now expects growth in the eurozone of 4.6% (against 5% previously) and 3.2% in 2022. Recovery will be helped by EU leaders’ agreement on 21 July1 of a €1.74trn seven year EU budget – the Multiannual Financial Framework – after protracted negotiations, plus a €750bn European recovery fund consisting of a mix of grants (€390bn) and loans (€360bn).

Despite hiccoughs in keeping the rate of new transmissions subdued, Germany has been the region’s star performer in its effective response to Covid-19. In his 10 August note, Focus Germany: How Strong a Q3 Rebound?, Deutsche Bank Research’s Chief German Economist Stefan Schneider forecasts a -6.4% contraction in German GDP this year (against -9% predicted in May), followed by 4% growth in 2021, but he does not expect the pre-Covid output level to be reached earlier than mid-2022. He adds the further caveat that “the pandemic is far from over”, and notes that “chances are high that for seasonal reasons and due to less vigilant behaviour in parts of society, infection rates will remain elevated in H2”.

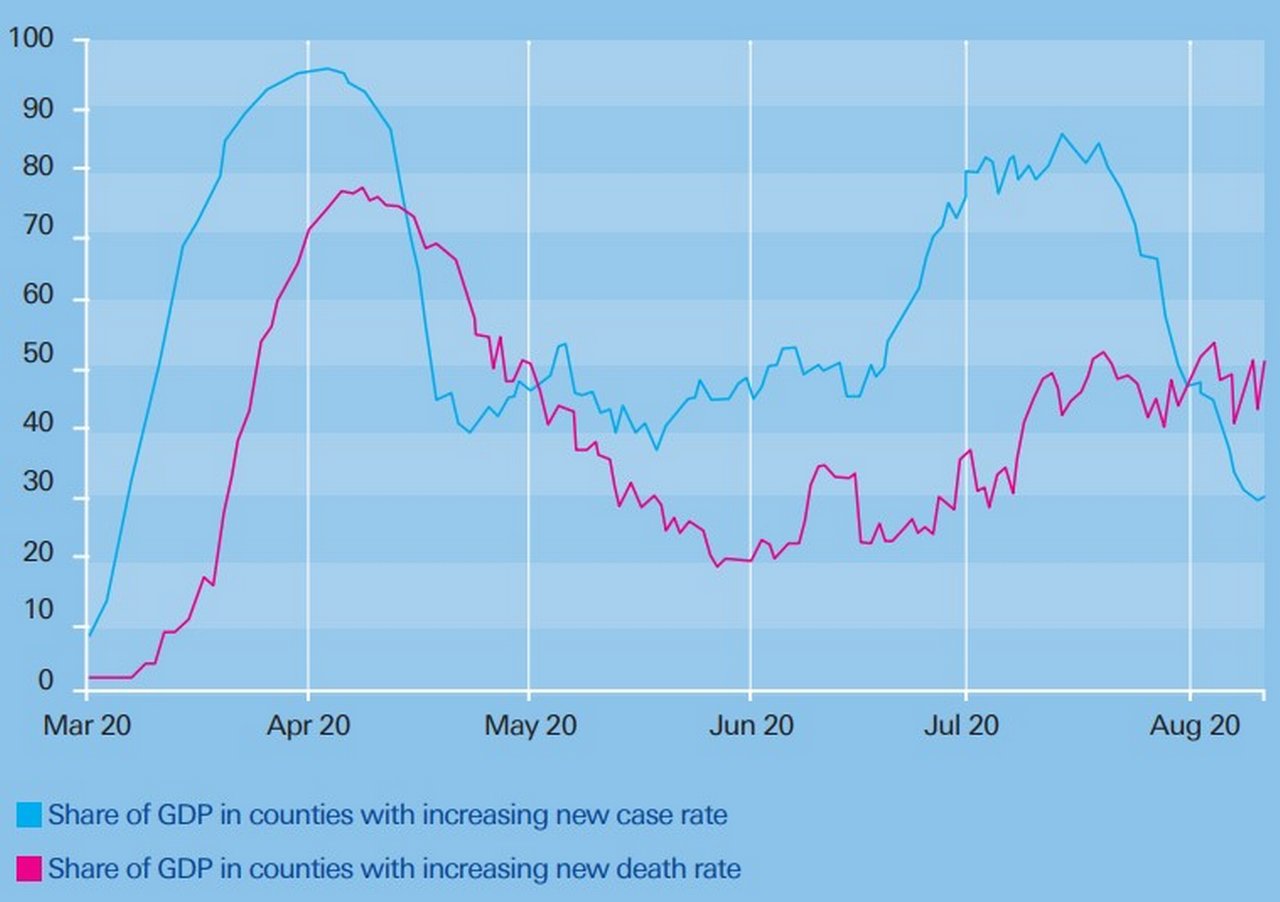

Figure 1: Percentage of US GDP from counties with increasing numbers of new cases and from counties with increasing numbers of new deaths

Source: BEA, USAFacts, Haver Analytics, Deutsche Bank

A US$1trn+ package

Perhaps the most unanticipated feature of the pandemic has been what World Outlook: Interim Update and Longer-term Projections (5 August) calls the “surprisingly persistent spread of the virus in the US”. Although setbacks to economic activity “have not been quite as severe as feared”, the ability to continue limiting the damage depends on “the ultimate size of the next fiscal package”.

The Research team predicts the estimated figure of US$1trn in May is more likely to be US$1.5trn–US$2trn, given the US’s poor statistics for new cases of Covid-19 and deaths. The team also believes that the possible availability of a vaccine by mid-2021 will help normalise economic activity and bring it forward to pre-virus levels by mid-2022, compared to a previous forecast of H1 2023. Nonetheless, the shock of the pandemic “will have scarring effects on the US economy, ranging from households preferring to save rather than spend for some time, structurally higher unemployment, and inefficiencies resulting from the closure of a significant number of small businesses”.

A rocky road

Behind various rescue packages and financial stimulus measures lies an unpalatable truth, as summarised by Deutsche Bank Research’s Chief Strategist Jim Reid: “The road ahead is paved with debt across the globe. The solutions are not yet obvious.” While the 2008 global financial crisis first saw talk move from billions to trillions as essential in preventing collapse, the Covid-19 crisis “has moved us towards $10trn plus being the bailout currency globally”.

More open to debate is whether the pandemic will bring down the curtain on 30 years of low inflation or, conversely, trigger a bout of deflation. Deutsche Bank Macro Strategist Oliver Harvey predicts the former, and believes this will be caused by the combination of massive government stimulus packages, retreating globalisation, increased bargaining power within certain sectors of the labour market, and the need to reduce large debt burdens. In a Konzept article, he posited that European government attempts to keep household incomes stable with job retention schemes are well intended but will result in “more money chasing after significantly fewer goods and services”.

The last word goes to The Economist, which expects the economic consequences of printing money to finance the stimulus to persist for decades. With output for many economies in reverse, and state intervention replacing what would normally be wages derived from those outputs, the magazine declared in its 25 July leader, entitled Free Money: When Government Spending Knows No Limits, that we are witnessing “a profound shift taking place in economics, the sort that happens only once in a generation”.

You might be interested in

CASH MANAGEMENT, MACRO AND MARKETS {icon-book}

Leaving Libor Leaving Libor

By the end of 2021, Libor will have all but disappeared. Helen Sanders looks at what treasurers should consider amid the phasing out of this widely used benchmark interest rate

CASH MANAGEMENT, MACRO AND MARKETS

When will digital currencies become mainstream? When will digital currencies become mainstream?

The Bahamas launched the sand dollar, a nationwide central bank digital currency (CBDC) last October. flow’s Graham Buck reports on why its move will be followed by others around the world over the coming months as CBDCs take on cryptocurrencies

CASH MANAGEMENT, REGULATION, MACRO AND MARKETS

Asian banks keep up to speed on ISO 20022 migration Asian banks keep up to speed on ISO 20022 migration

The new global language for financial communications is very much a work in progress. In this article written for The Asian Banker, Nancy So assesses how banks across the region measure up