8 December 2022

Although COP27 at least kept the global climate change conversation going, agreement and common frameworks still seem some way off. flow shares insights from two Deutsche Bank reports setting out some practical next steps

MINUTES min read

The world is “on a highway to climate hell with our foot on the accelerator,” warned UN secretary general António Guterres ahead of the November 2022 COP27 climate summit in Egypt’s Sharm El-Sheikh.

This article shares findings from two Deutsche Bank publications – the first being Deutsche Bank Research’s report on COP27, and the second, an analysis by Deutsche Bank Private Bank’s Chief Investment Officer of the impact cities have on climate change and what can be done about this.

COP27 outcomes

Overall, as the Deutsche Bank Research team noted in their report, Top 8 notable takeaways from COP27, the event “took place against a difficult geopolitical backdrop, rising inflation and an energy security crisis that some nations interpret as support for energy diversification strategies that align with fossil fuel growth”. It was not a surprise therefore, given the worries about energy security, that coal remained the only energy source agreed to be phased down.

A loss and damage fund established, but “agreement was rushed, and development will take time”, says the report. It makes the point that “experts estimate US$100bn a year will be needed by 2030 to help communities repair and rebuild from climate-related disasters. The commitments, set out below, falls short of this estimate”.

However, while the report says that “progress on climate objectives could have resulted in more agreement on establishment of directives”, the team believe “the annual United Nations COP climate conference does help to hold governments and regulators accountable on a global stage (every year)”.

But nations can’t just talk. “A different geopolitical backdrop would also allow for more productive conversation. That said, while there were several notable updates from this year's event, next year's COP will be expected to make more progress on directives to achieve climate mitigation, adaptation and funding,” conclude the authors.

Cities and climate change

“Rising sea levels will force people living in the city to either adapt or leave”

One aspect of climate change that merits a specific focus is the world’s cities and their impact, says Markus Müller, Deutsche Bank’s Chief Investment Officer ESG and Global Head Chief Investment Office. “Rising sea levels will force people living in the city to either adapt or leave. The key question is whether many cities will still be habitable in future,” he warns.

In the Deutsche Bank Wealth Management report, Cities under threat, real estate investment and climate change, Müller sets out a framework for mitigating the economic and environmental threat that cities pose to the environment. This centres around the following three summary points:

- Building and construction accounts for a large share of global energy use and emissions.

- Cities will have to adapt to protect themselves and mitigate their climate change effects.

- New financing models will feature public/private partnerships, targeting and philanthropy.

The report opens with the observation that cities exacerbate climate change by accounting for 70% or more of global CO2 emissions. At the same time, they are exposed to the impact of climate change through floods, excess heat, other extreme weather events and changing patterns of disease.

Real estate is a key issue, with regulations in many cities aimed at reducing the emissions of individual buildings and address other sustainability issues. Müller expects the future scope of city responses to climate change to broaden and deepen, impacting on real estate investment and how it is assessed.

Global warming and urban threats

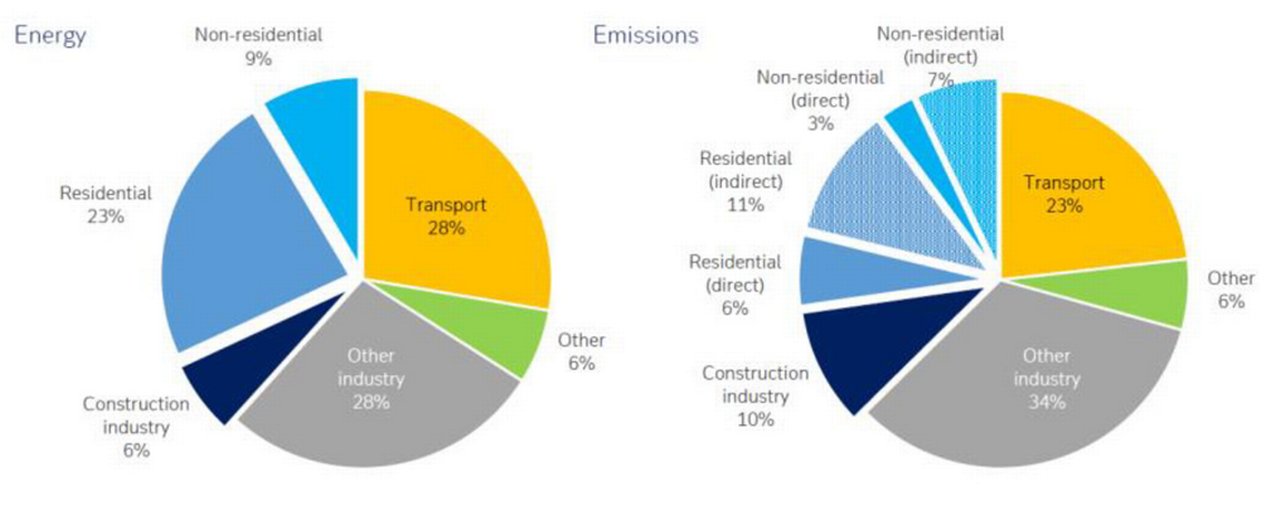

Figure 1: Sectoral contributions to energy-related CO2 emissions

Source: IEA and Global Alliance for Buildings and Construction, Deutsche Bank AG. Data as of October 2021.

Building and construction accounts for about 36% of global final energy use and 37% of energy-related CO2 emissions. Following a decade of increases, pandemic disruption saw building emissions fall 7% in 2020. But achieving the 2030 net zero target requires substantial further declines and will involve multiple choices such as deciding when to retrofit an old building rather than building a new one; choices complicated by the increasing urbanisation of many emerging market economies.

Cities attract workers and well-functioning cities are essential to prosperity, generating more than 80% of global GDP. Further urban growth seems inevitable, with the global city population forecast by the UN to rise by 2.5 billion by 2050.

The report notes that climate change is already increasing the difficulties of urban life, as higher levels of air pollution and the “heat island” effect are felt. A US study suggests the latter causes city temperatures averaging 0.6-3.9 °C higher than in outlying areas.

This heat island effect is set to increase further, in line with greater urban sprawl. The frequency of extreme weather events is already rising, with one study estimating the annual economic costs in the EU at around €12bn.

Cities both contribute to and are impacted by a deteriorating environment. The growing incidence of very hot days is creating water supply problems, transport system disruption and health hazards from direct heat and infectious disease risks. Poorer urban migrants in slums on city outskirts are particularly vulnerable.

Controls and adaptation

Imposing CO2 emission controls and other sustainability criteria at national and local level has been one positive response. While well-established initiatives such as Germany’s have noticeably reduced emissions, around two in three countries still lack mandatory energy building codes. High performance properties – such as net-zero energy buildings – still account for under 5% of construction in most markets, reports the International Energy Agency (IEA). Better data may result in some counter-intuitive solutions: retrofitting old buildings may be greener than building from scratch as the carbon effects of a new building can take 10-80 years to be neutralised.

Alongside regulation, adaptation strategies to mitigate climate change come in many forms. Engineered solutions may attempt to radically restructure cities to improve efficiency, Paris’s “15 minute” city urban model, for example, encourages self-contained neighbourhoods to reduce vehicle emissions. Cities can also gain resilience from walls to contain flooding or enhanced sewerage systems that accommodate overflows. These solutions are often substantial – such as Shanghai’s 520km of seawalls – and expensive: Tokyo’s flood control system cost US$2bn, but by 2019 had prevented estimated US$1bn in damage.

Nature-based solutions (NbS) offer an alternative form of adaptation. Preservation or development of natural coastal protection, such as mangroves, can make coastal cities more floodproof, while NbS and engineered solutions may be combined. China’s Sponge City Initiative, launched in 2015, reinforces the ability of cities to absorb excess rain when ground is increasingly covered by concrete or asphalt. Sponge city strategies focus on making roads and pavements more permeable and storage of the water collected easier. China has trialled green roofs, underground water storage chambers and rain gardens, and sinks.

The results are promising; adopting porous bricks and concrete could lower pavement surface temperature by 12 and 20°C respectively and the air temperature by up to 1°C, with resulting benefits for both long-term carbon emissions and immediate individual wellbeing.

The downside is cost: China’s 16 sponge cities developed in 2015-17 required investment of about US$3bn. Additionally, good data is needed to prioritise initiatives: the multi-institutional project “Cooling Singapore” will build a computer model – aka “digital urban climate twin” – to analyse the effectiveness of various heat mitigation strategies.

Cities will also review effective services provision, such as cooperatives to encourage the use of sustainable energy sources, while Vienna is considering development of a district cooling initiative to lessen dependence on individual air conditioning systems.

Longstanding initiatives to reduce traffic have recently focused on electric vehicles, with the Biden administration pledging to finance the US electric car charging infrastructure. But technology has already contributed to improving traffic flow, with the non-car alternatives of public transport, walking and cycling key.

Climate change presents other broader social challenges to cities. In many emerging market cities, urban migrants settle in cramped slums on the outskirts, exposed to flooding and with inadequate infrastructure, water and food supplies and health care. There are spill-over effects on the city’s other residents. Prevention requires greater attention to the housing of residents – particularly in rapidly-developing cities – managing public transport and investment in human capital (education, health, nutrition, vaccinations, drinking water supply, improved maternal health). Real estate investment will be part of this process, working with local governments and non-governmental organisations (NGOs).

When city adaptation is not feasible the ultimate alternative is relocation, particularly for coastal cities. By 2029 Indonesia will have re-sited its capital, Jakarta, inland to Nusantara, at a cost of around US$30bn.

Investment implications

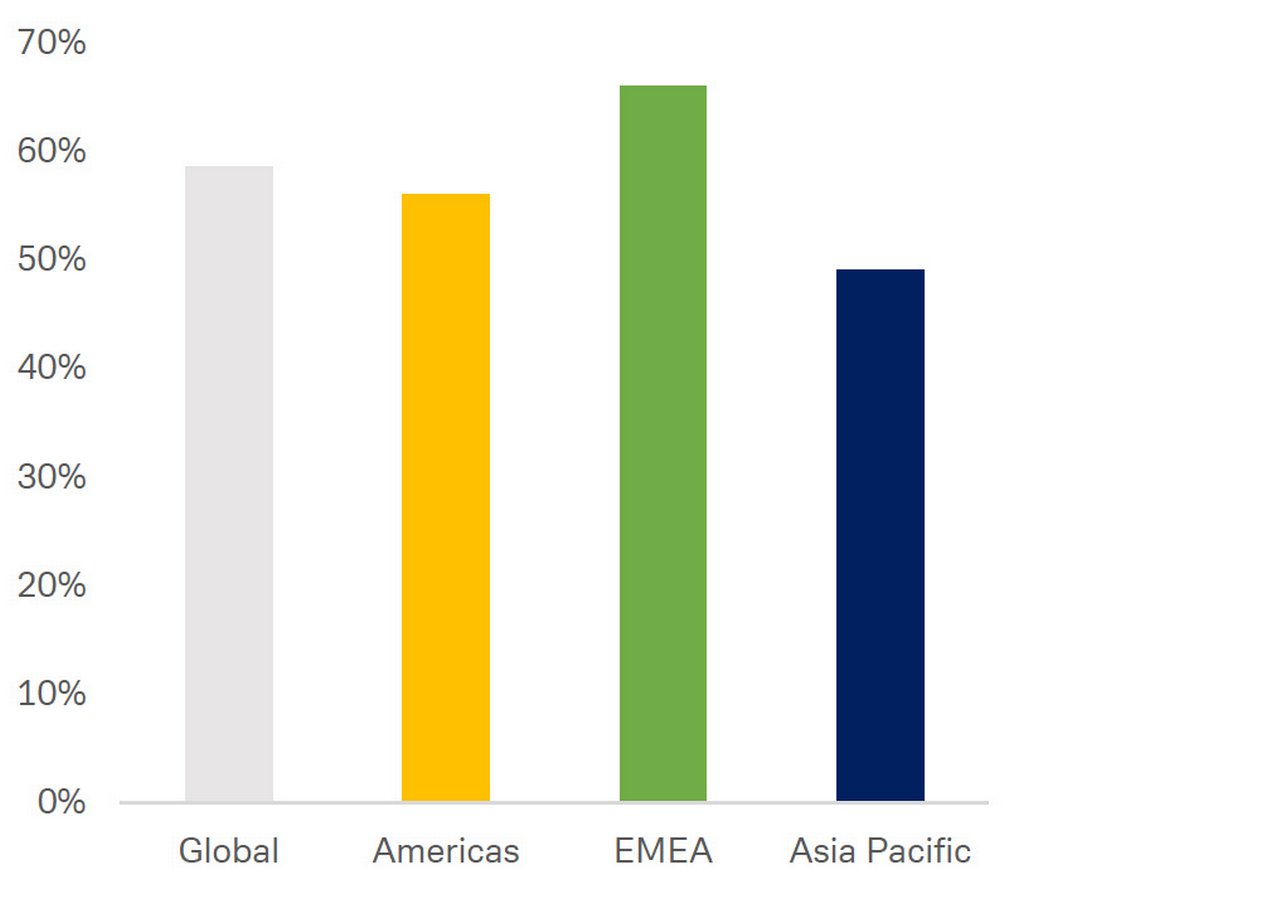

Figure 2: Real estate investors increasingly incorporating ESG factors

Source: CBRE Global Investment Intentions Survey 2021, Deutsche Bank AG. Data as of June 2021

Real estate investors already heed environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors: 60% of respondents to CBRE Group’s 2021 Global Investor Intentions Survey confirmed they already incorporated ESG criteria into their investment strategies, with the Americas, EMEA and Asia-Pacific all recording a stronger focus on ESG issues than in previous years.

Müller now expects analysis by real estate and other investors to become detailed and broader in scope. As the scale of potential climate change impacts is evidenced, realisation will grow that this extends beyond assessing the carbon footprint of individual buildings. To keep cities functioning while reducing their overall environmental impact requires three interconnected developments:

- Better understanding of the overall impact of investment

- Improved methodologies for classifying ESG investment

- New financial approaches to channel relevant investment

Better understanding of the overall environmental impact of different investment decisions, on a case-by-case basis, depends initially on improved scientific data and modelling such as the impact of city development on CO2 emissions. Moving beyond this to prioritising investment decisions requires an additional framework that builds on specific scientific predictions to develop an overall accounting framework for environmental and economic impact. This has begun to emerge through natural capital accounting systems. Individual real estate and/or other projects are no longer assessed in purely economic terms, but also on issues such as carbon emission levels and impact on the natural environment. But viewing nature as a capital stock which needs to be carefully maintained to deliver essential ecosystem services forces a rather different approach, taking assessment of external impacts to a whole new level and a more holistic way of choosing between different options.

Natural capital accounting has advanced via initiatives such as the UN’s System of Environmental Economic Accounting (SEEA) launched in 1993 but may take time to become fully accepted. In the interim, the emphasis is likely to fall on ESG methodologies to provide an investment roadmap for real estate and climate change.

Better data will assist new financial approaches, but the surrounding institutional framework will also be important, such as international financial incentives to encourage countries to move to more sustainable level from the World Bank and the UN. These are complemented by new internationally agreed financing mechanisms, often targeting the natural world, such as the Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation (REDD+) scheme. Finance for city development may not sit easily in such schemes, due in part to the range of parties involved. Making sustainable cities involves some consensus on “who does what” before debate begins on the underlying issue of who pays for what.

Working together

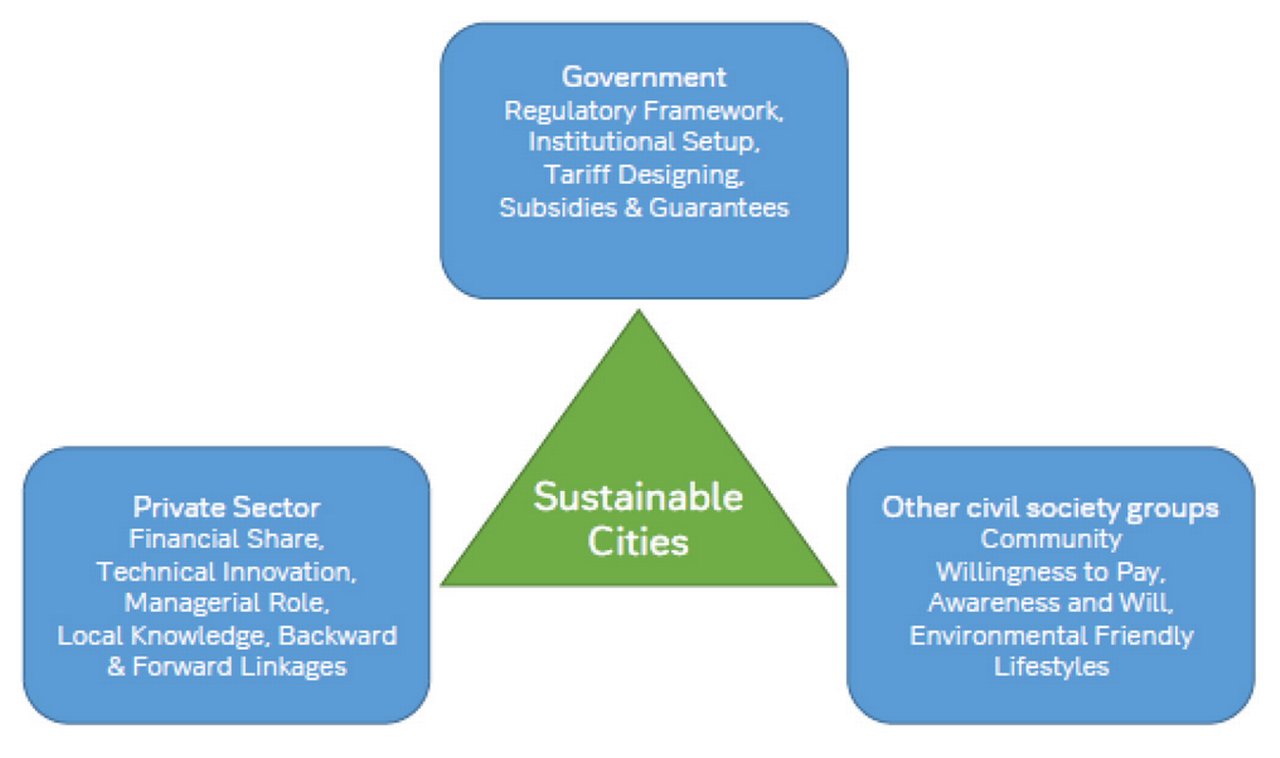

Figure 3: Contributors to sustainable cities

Source: United Nations Environment Programme, Deutsche Bank AG. Data as of October 31, 2021

As summarised in Figure 3, the approach of the UN and others resembles a triangle of responsibilities between government, private sector and other civil society groups. In reality, “government” will itself have several components and trigger financial battles between national and local governments over the financing of city transport and other infrastructure.

This suggests a need for public-private finance partnerships to improve investment levels and make cities work better. Innovative financing models should also allow better targeting of private finance on infrastructure.

The importance of social issues would also suggest increased scope for financing with a philanthropy component, designed to generate commercial returns and echoing the role played by philanthropists towards improving housing on a commercial basis in the rapidly growing cities of the 19th century

There is no perfect solution as cities have varying problems and will employ different mixes of policy responses. But Müller concludes that the overall economic and environmental threat posed by large conurbations and the scale of the problem, means that real estate and infrastructure investment in cities may be entering a period of significant change.

Deutsche Bank reports referenced

Top 8 notable takeaways from COP27 by Debbie Jones, Luke Templeman and Tejasvini Viraj, Deutsche Bank Research, 23 November 2022. The summary sheet is available here and the full report available to Deutsche Bank Research subscribers can be downloaded here

Deutsche Bank Private Bank

CIO Special Report: Cities under threat: real estate investment and climate change by Markus Müller Chief Investment Officer ESG & Global Head Chief Investment Office, Deutsche Bank (I November 2022). This can be downloaded here

Sustainable finance solutions Explore more

Find out more about our Sustainable finance solutions

Stay up-to-date with

Sign-up flow newsbites

Choose your preferred banking topics and we will send you updated emails based on your selection

Sign-up Sign-upYou might be interested in

SUSTAINABLE FINANCE, TRADE FINANCE, MACRO AND MARKETS

Europe’s energy crisis: Ten green bottlenecks Europe’s energy crisis: Ten green bottlenecks

Winter is coming and what will bridge the energy gap created by the recent shutdown of Russian gas supplies and challenging emissions reduction targets, asks Deutsche Bank Research. flow shares some key points of a new report on Europe’s energy crisis

Sustainable finance, Trade finance and lending

How to manage transition to net-zero How to manage transition to net-zero

As economies around the world pledge their commitment to net-zero emissions by 2050, companies need to step up their decarbonisation plans. Deutsche Bank’s Lavinia Bauerochse reflects on how this is changing the role of banks and why transition is becoming a core element in client conversations

Sustainable finance, Trade finance and lending

Towards 2050: the case for gas Towards 2050: the case for gas

The COP26 summit saw governments commit to achieving Net Zero by 2050, but this will prove “incredibly difficult to achieve”, a recent Deutsche Bank Research report concludes. flow’s Clarissa Dann examines why its analysts believe that although the world’s appetite for coal and oil must be cut, gas plays a vital role in keeping the lights on