17 May 2023

In the latest Asia Corporate Newsletter, Deutsche Bank Research notes that the US banking crisis has lent strength to global economic headwinds, but Asia is well positioned to withstand the buffeting, with China’s reopened economy as a key driver. flow provides a summary of the report’s insights

MINUTES min read

Coronavirus lockdowns and a property market downturn combined to apply the brakes on China’s growth in 2022. The world’s second largest economy expanded by 3%, which by previous standards was anaemic and industrial production rose only 3.6% against 9.6% in 2021.

However, before the year was over the picture changed. Chinese authorities abruptly abandoned the country’s stringent zero-Covid policy in December. The resulting rebound in the early months of 2023 is set to boost not only China’s growth but that of its neighbours, reports Mallika Sachdeva, Head of Asia Macro Strategy at Deutsche Bank and Editor of the Asia Corporate Newsletter.

In the April edition, titled Q2 2023: holding its ground, she notes how the recent US banking crisis has intensified headwinds to the global economy by tightening credit conditions and increasing the risk of recession. Asia’s exports have not been exempted from the impact, but the region is well positioned to hold its ground better than others.

Much of this is due to China’s “economic acceleration”, helped by improving credit conditions and supportive government policy. This particularly benefits the 10 Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) member countries of Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam.

In addition, Asia has suffered a relative absence of the post-Covid headaches afflicting North America, Europe and elsewhere. “Asia’s financial system appears in better health,” comments Sachdeva. “Asian currencies are fairly valued, and corporates have hoarded USD deposits. We are thus not expecting sharp weakness in Asian FX as seen in 2007–08.”

And while the US Federal Reserve, European Central Bank (ECB) and Bank of England (BoE) have embarked on steep interest rate hike cycles since late 2021/early 2022 – each now apparently at or near its peak – Asian central banks’ policy tightening has been more modest and they will correspondingly not need to lower rates as much when the anticipated “significant cuts” get underway in 2024 “which will rotate the hedging environment in favour of Asian exporters.”

Reading the Fed

A trio of US regional bank failures in March and the more recent rescue of First Republic by J.P. Morgan have, says the report, led to tightening bank lending conditions and revised forecasts on the duration of the Fed’s policy cycle. Sachdeva and team correctly anticipated one further hike from the Fed, a 0.25% rise to 5–5.25%, would follow on 3 May and now expect US interest rates to remain stable before 225 basis points (bps) cuts follow in 2024, mostly in H1. Europe’s less vulnerable banking sector should mean that the ECB’s rate, now at 3.25%, still has further to rise, peaking at 3.5–4%, and with lesser easing to follow.

However, the balancing act required to tame stubborn inflation in the G10 economies (Japan’s apparently modest rate of 3.1% is still a 41-year high) while avoiding an economic “hard landing” make for tough policy choices. US recession remains a distinct possibility; a European recession less so “but the economy there too could stagnate for the next few quarters depending on how much/long bank funding costs rise”.

In this uncertain environment, money market funds (MMFs) accreted nearly US$340bn in the period just before and after the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) in March, the second-biggest increase ever. Whereas previous episodes saw MMFs gain at the expense of another asset class such as equities or emerging markets, this time it represents a shift away from bank deposits, with MMFs increasingly seen as a substitute vehicle to hold cash.

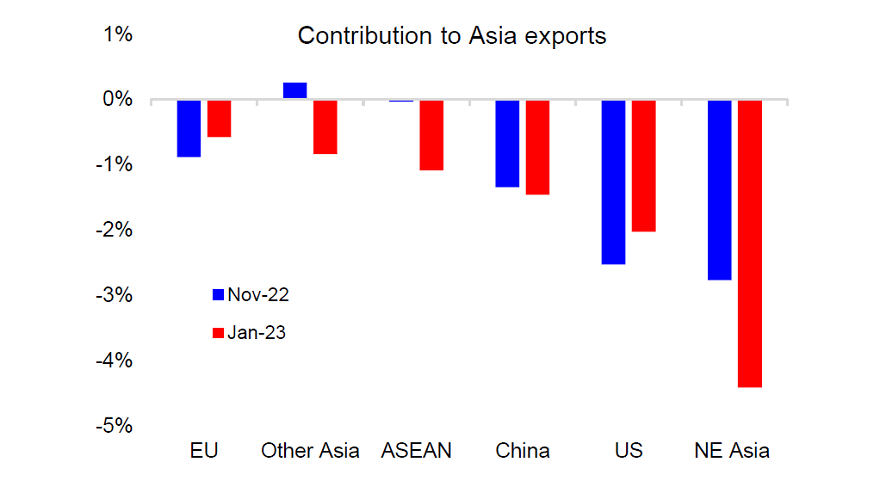

With the US economy showing signs of weakness, China’s reopening for business promises will hopefully provide some to support Asian exporters. The year began with Asian exports to all major regions decreasing and electronic goods particularly hard hit, with the US and North Asia leading the decline in terms of demand, while EU demand was less of a drag.

Figure 1: Asian export growth has been negative to all major regions, US demand in particular is worse than in China and the EU

Sources: Deutsche Bank, Bloomberg Finance LP, CEIC

China's post-Covid recovery momentum has already exceeded market expectations, with services activity quickly returning to pre-Covid levels and even the moribund property sector reviving.

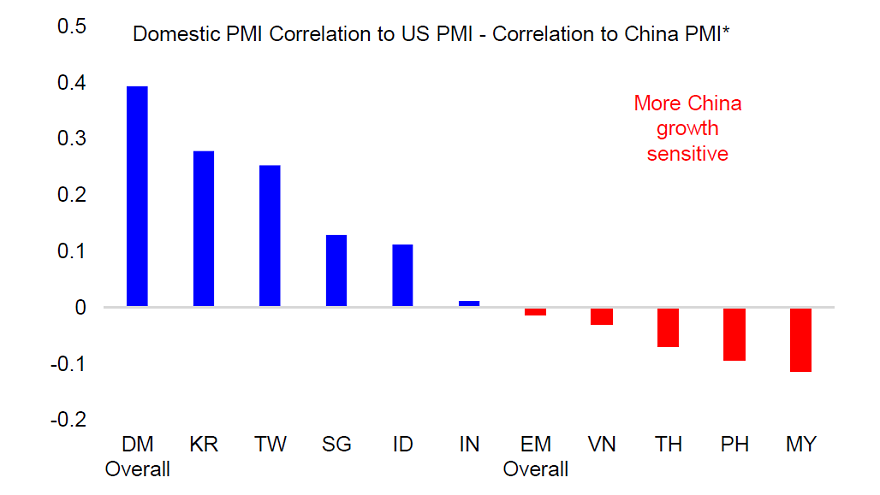

The country’s contribution to Asian exports is only now stirring back to life, but Deutsche Bank economists expect a strong recovery, with GDP growth at 6.0% in 2023 and 6.3% in 2024 to most benefit those economies that are more leveraged to China than US growth. Several ASEAN economies, including Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam have become more correlated to China “while North Asian economies like Korea and Taiwan could face a bigger drag from US than lift from China”.

Figure 2: As China’s recovery plays out, ASEAN economies are set to benefit more from China’s lift than suffer from the US drag

Sources: Deutsche Bank, Bloomberg Finance LP, CEIC

A robust banking system

The string of US bank failures has fed concerns that Asia might have the same to fear. The newsletter cites several reasons why these worries are exaggerated:

- Asian banks have built ample capital reserves over minimum regulatory requirements.

- Asian banks have stickier deposit bases.

- Refinancing needs are lower. The number of Asian countries borrowing from foreign banks has been declining, and those that are borrowing have strong external asset positions and FX reserves.

Additionally, Asia’s Financial Stress Index (FSI) remains low, both compared with the US and historical levels. So potential spill-overs from the US banking crisis directly impacting Asian banks appears to be a lesser risk than the US tightening bank lending standards and causing weaker American business conditions.

Asian currencies are also judged to better placed than they were at the time of the 2007–08 crisis due to several factors: foreign investor positioning is significantly lighter, with considerable outflows from Asian equities in recent years in contrast to inflows from 2002-07; and Asian corporates have several years of accumulating USD deposits (unlike the heavy short USD forward positions in 2007), so USD funding stress is less apparent.

“We see China-ASEAN trade volumes are set to continue to boom”

Other positives are the fillip from China’s post-Covid recovery, particularly for services exporters and those ASEAN countries more sensitive to China than US growth; also the fact that Asian currencies were mostly overvalued at the time of the crisis but are now more realistically valued or even cheap.

Drivers of growth

“Asia has hiked less than the Fed, and will cut back less too,” states Sachdeva and her team. On average the region’s central banks have instigated 40% of the hikes applied by their US counterpart since early 2022. Countries that tightened more – such as the Philippines, Korea, India and Indonesia – will also cut back further, while others that tightened less like Malaysia, Thailand and Taiwan have more limited room for reductions.

The region’s two heavyweight economies of China and Japan are also likely to be normalising policy in the next two years: across liquidity in the former, and in the latter yield curve control and negative rates. Here too, China’s recovery and Asia’s more robust banking system will further help to bolster the region’s growth.

This suggests a fair outlook for corporate bonds and also equity capital financing, now set to resume thanks to policy support. Since the start of 2023, China’s improving credit status has largely been reflected by activity in the renminbi (RMB) loan market, while corporate capital market financing or credit bond issuance contributed less to the overall growth in aggregate social financing.

In contrast to developed markets where merger and acquisitions (M&A) and credit cycles are set to decelerate, China is supporting targeted sectors such as technology, semiconductors and green development, as credit conditions improve. Add to this progress on debt restructuring deals for defaulted property developers, a friendlier regulatory environment for the private sector, the launch of registration-based initial public offerings (IPOs) and expansion of the Stock Connect Scheme (launched November 2014) to more eligible stocks.

Sachdeva and team expect both the RMB credit market and A-H equity market (where A shares trading is limited to mainland Chinese citizens and H-shares are open to all investors) to become key sources of financing for China’s corporates.

They also believe Chinese policy is supportive of the credit acceleration process, reflected in two 25bps cuts by the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) in November 2022 and March respectively to the reserve requirement ratio (RRR), the amount of cash banks must keep in reserve at the central bank to support lending and strengthen economic recovery. The cuts reflect several policy aims:

- To manage the risk of tighter domestic liquidity due to the credit recovery;

- To manage spillover risks from recent global financial turmoil; and

- Alleviating government debt supply risk to commercial banks.

Chip wars

A less welcome recent development has been the decoupling in semiconductor trade, also known as the “chip wars”, between the world’s two biggest economies as the US weans itself off dependency on China as its main supplier.

US-China relations began deteriorating with Donald Trump’s accession to the White House after years of close economic and signs of trade and technology decoupling are now evident. “Given the various roadblocks enacted by the US, as well as the high degree of dependence China currently has on foreign inputs for technology, China will need to focus on a '3 Bs' strategy: Build (develop new technology in-house), Borrow (attract FDI), and Buy (buy technology),” the team suggests.

“Separately, China could also use the opportunity to leverage its current position in the production of more mature technologies, raising the cost of decoupling for other countries.”

Biggest potential beneficiary of the chip wars is probably ASEAN, which is building a stronger presence in the semiconductor supply chain, Singapore in manufacturing and Malaysia in integrated circuit (IC) packaging and testing. Korea could also gain market share from Chinese peers as the US blacklists more Chinese firms. However, Taiwan’s increasing geopolitical tensions with its neighbour means it is likely to benefit least, particularly if customers look to relocate their semiconductor supply chain elsewhere and India does not yet appear ready to become an immediate rising star.

A China-ASEAN trade bonanza

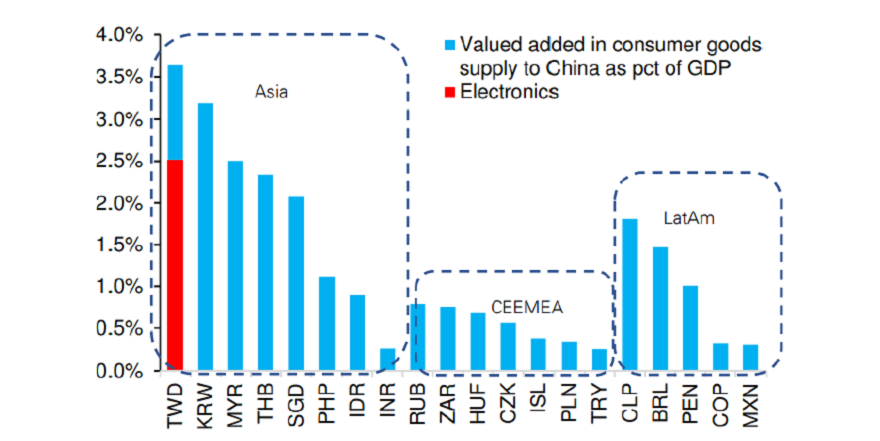

China-ASEAN trade is set to continue booming, the report concludes, with consumption set to be the biggest driver for China this year and countries such as Thailand and Malaysia benefiting from China’s revival in tourism and consumer goods demand.

Figure 3: A consumption recovery in China would be very positive for select Asian economies’ trade with Asia

Sources: Deutsche Bank, Bloomberg Finance LP, CEIC

And while increasing tensions with the US, tech export controls, near-shoring/friend shoring and diversification of supply chains all threaten to be a drag on China’s long-term growth, they will create unique opportunities for the rest of Asia, especially ASEAN, who will acquire some of its manufacturing and export capacity.

“With parts of the supply chain relocating to ASEAN particularly for assembly, but many intermediate parts still manufactured in China, we see China-ASEAN trade volumes are set to continue to boom,” the team concludes.

One last unknown that “could affect the stability and continuity of current policies” is ASEAN politics. Thailand’s election on 14 May delivered a strong result for the country’s opposition parties which appear to have won a decisive victory over the military-backed government that has ruled for nearly a decade. The next few weeks could be uncertain as alliances shape up, and the Senate votes in a combined vote to select the Prime Minister. Malaysia is due to hold a few state elections in July, which will be seen as a referendum on premier Anwar Ibrahim’s Pakatan Harapan (PH) coalition. Further ahead is Indonesia, which does not go to the polls before next February but where “a potentially competitive and unpredictable three-wary race” is already shaping up.

Deutsche Bank Research reports referenced

Asia Corporate Newsletter – Q2 2023: Holding its ground by Mallika Sachdeva, Sameer Goel, Linan Liu, Perry Kojodjojo, Bryant Xu, Tim Baker and Joey Chung (April 2023)