31 July 2020

As cases of Covid-19 surge past 17 million, the global debt mountains that the pandemic expanded seem perpetually unscaleable. flow’s Clarissa Dann and Graham Buck take a closer look at how the ruies of macroeconomics are being rewritten

The adage ‘the operation was successful but the patient died’ comes to mind as governments around the world spend billions on Covid-19 financial rescue packages. These temporary lifelines have, for now, warded off the spectre of mass unemployment and social unrest.

However, the basic economic consequences of printing money to finance the stimulus and adding to an already vast debt mountain look set to be around for decades. With output for many economies having gone backwards, and state intervention replacing what would normally be wages derived from those outputs, we are seeing , as The Economist put it in its 25 July leader entitled Free money, “a profound shift taking place in economics, the sort that happens only once in a generation”.

On 16 July, the Institute of International Finance (IIF) Global Debt Monitor reported how global debt soared to a record 331% of GDP (US$258trn) in Q1 2020. Worryingly, it adds, “The available data on issuance suggests that the pace of debt build-up has accelerated since March, largely reflecting the massive global fiscal and monetary response to the pandemic.” (see Figure 1). The IIF noted that gross debt issuance hit an eye-popping record of US$12.5trn in Q2 − versus a quarterly average of US$5.5trn in 2019. Governments accounted for over 60% of gross issuance in Q2.”

Figure 1: Global debt topped US$258trn in Q1 2020

Source: IIF, BIS, IMF, National sources

"The road ahead is paved with debt across the globe. The solutions are not yet obvious!"

In Covid-19 and inflation (20 May), we reflected on how, as Jim Reid, Chief Strategist, Deutsche Bank Research observed, “The GFC moved us from ten billion being a big number to a trillion being the new bail-out currency. This Covid-19 crisis has moved us towards ten trillion plus being the bailout currency globally.”

This article circles back to the basic issue of whether or not a debt burden of this size can be managed (or at least lived with) while interest rates remain low, and the prospect of inflation reducing its impact looks remote for the foreseeable future. It also revisits the role of central banks and their governments.

After Suez

More than 60 years ago, a few months after Britain’s Prime Minister Harold Macmillan had declared “most of our people have never had it so good”, UK Chancellor of the Exchequer Peter Thorneycroft wrote a note on 14 October 1957 about the “Economic Situation”, the contents of which are now available from the UK’s National Archives papers. We have included it as it is a shining example of a chancellor spelling out the consequences of spending more than resources allowed.

“We have been near to the edge of economic disaster. We are still near the edge. Over the past two months we have lost £185m from our gold and dollar reserves,” Thorneycroft warned. “The reserves at the end of September were down to £660m, only two-thirds of what they were at the end of 1954, despite the £200m which we drew from the International Monetary fund (IMF) last year and the £37m which we gained by not paying last year’s interest on the American loan.

“A continued run on the reserves at the rate which have recently experienced would exhaust them in six months. In practice, the crack would come much sooner. Within weeks it would become clear that the rate could not be held. Increased leads and lags and the run which would be started by the central core of holder of sterling in the sterling areas and elsewhere could and would start the reserves pouring out many time faster. In the collapse which would follow the cost of our imports of essential foods and raw materials would rise sharply, adding very much to the dangers of an inflationary spiral at home…"

The economic shock in question was the Suez crisis the previous year, and in his resignation letter to Macmillan on 6 January 1958 because of irreconcilable differences over austerity measures, Thorneycroft said, “I regard the limitation of Government expenditure as a prerequisite to the stability of the pound, the stabilisation of prices and the prestige and standing of our country in the world.”

Fast-forward to 2020 and the UK is hardly the only government to kick the can down the road with borrowing, but Covid-19 has triggered such huge proportions of can-kicking, that a rethink of the laws of economics is inevitable.

“Who could have imagined six months ago, that tens of millions of workers across Europe would have their wages paid for by government-funded furlough schemes, or that seven in ten American job-losers in the recession would earn more from unemployment-insurance payments than they had done on the job?” asked The Economist in its briefing “A new era of economics” (25 July 2020).

EU recovery

Empty restaurants in St Mark’s Square, Venice

This escalating debt load will have weighed on the minds of leaders from the 27 European Union member states at their Council meeting held 17 to 21 July; the first such gathering since before the coronavirus pandemic disrupted normal life. After five days, a joint response to the “unprecedented economic challenges” posed by the Covid-19 was agreed.

As Deutsche Bank Research economists Kevin Koerner, Barbara Boettcher and Mark Wall noted in their paper of 21 July Focus Europe - EUR750bn EU Recovery Fund: Deal!, reaching consensus appeared impossible at times, but a financial package totalling €1.82trn resulted from the protracted negotiations. It comprises a €1.074trn seven-year EU budget – the Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) – plus a €750bn European recovery fund consisting of a nearly half-and-half mix of grants (€390bn) and loans (€360bn).

To reach consensus, European Council President Charles Michel “repeatedly adjusted (downsized) his original proposal to meet the demands of frugal members”,– the so-called ‘frugal four’ being the Netherlands, Austria, Denmark and Sweden. “The €390bn grants facility agreed is a significant cut compared to the €500bn called for by France and Germany, but the share of grants in the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) was slightly increased to €312.5bn.”

The agreed package is seen as having two key positives from the financial markets’ viewpoint:

- Precedent: “The Recovery Fund is the EU’s first common counter-cyclical instrument; there is no austerity requirement; the Recovery Fund is an opportunity to support a large-scale climate change package,” note Deutsche Bank’s economists.

- Optimal design. “From a macroeconomic perspective, the optimal Recovery Fund would be (i) large enough for the scale of the COVID crisis, (ii) targeted at the most growth-enhancing investment opportunities (in the hardest hit countries and sectors), and (iii) complemented by structural reforms. The agreement is a reasonable attempt to satisfy all three.”

But the Deutsche Bank team points out that the Recovery Fund is a “temporary instrument” to address the Covid-19 crisis and suggests that “at some point, euro members will have to face the question of whether a permanent, euro area-specific instrument will be created – including the implied loss of fiscal sovereignty of the members that this would necessarily bring”.

Their analysis also hones in on weaknesses in the MFF. “Final agreement on the MFF has shown that once again protection of the status quo (in particular cohesion and agriculture) has prevailed over the need to focus on the future (in particular innovation and digital),” they commented.

“This makes the deal more short-termist, less focussed on the long term and suboptimal when it comes to the union’s long-term competitiveness. It also still needs to be shown how the commitment of 30% of funds for climate action can be implemented and enforced in practice.”

The ECB’s cliff edge

Negotiations for the Recovery Fund began a day after the European Central Bank’s (ECB) press conference on 16 July, at which its President, Christine Lagarde, spoke on the monetary policy outlook for Europe.

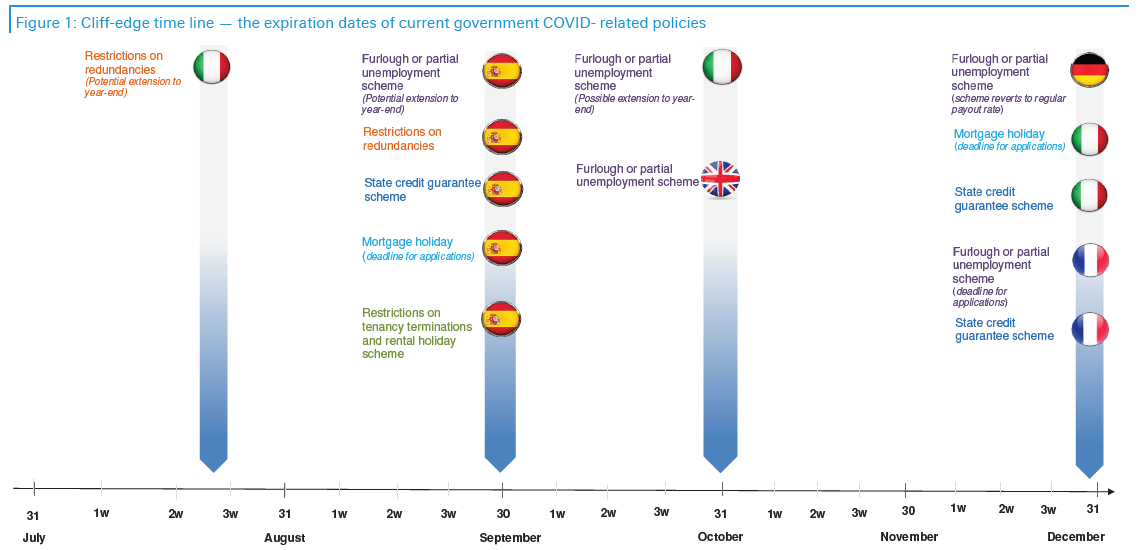

This was analysed by Mark Wall and colleagues in the 24 July Deutsche Bank Research paper Focus Europe – Warning: Step back from the cliff edge, with the team taking two main messages from the presentation. “First, the ECB is committed to its easy policy stance and to spending the entire Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP) envelope unless there is an unlikely significant upside surprise.” The PEPP, a €750bn asset purchase programme, was first unveiled by the ECB in March and subsequently increased to €1.35trn in early June.

“Second, the ECB warned European fiscal authorities that the economic recovery will not be sustained if temporary policies like the state credit guarantees and furlough schemes are allowed to roll off as planned in several large members states in the second half of 2020.”

The team notes that the ECB’s monetary policy since the pandemic reached Europe is a combination of PEPP and the third of the Targeted Longer-term Refinancing Operations aka TLTR03 and also introduced in March 2020 (TLTR01 dates from June 2014; TLTR02 from March 2016). Lagarde has described TLTR03 as “vastly successful” although “it is only partly influenced by the ECB… and also relies on the state guarantees”. So she sent out a clear message “that an abrupt withdrawal of the guarantees — and other temporary policies — in the second half of 2020 would be a mistake”.

The bottom line, the paper’s authors conclude, is that “the economic recovery is not self-sustaining yet” as the recent signs of recovery may prove temporary and “a continuation of monetary and fiscal policy cooperation is necessary”, which includes costly temporary facilities, such as the furlough schemes (see Figure 2 below).

At the same time, governments are urged to “think about the optimal use of their balance sheets. If an extension of furlough schemes equates to sustaining unsustainable businesses, it might be a better use of fiscal space to support new businesses and new growth, for example, by financing new skills training for the unemployed”.

Figure 2: Current expiration date of Covid-19 related relief programmes

Source: Deutsche Bank

* The 30 July edition of Deutsche Bank Research chief strategist Jim Reid’s morning Macro Strategy Note reports: “The Spanish government has extended the deadline for corporates to apply for loan guarantee schemes from the end of September to 1 December”.

Crunch time for the Fed

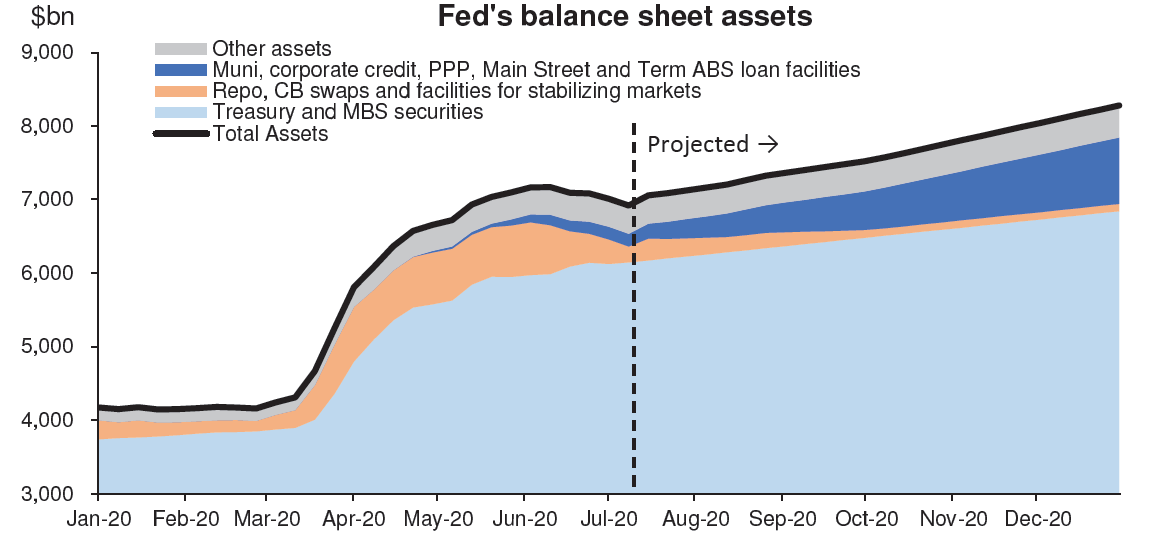

Meanwhile, in the US the Federal Reserve “is nearing a critical juncture in its response to the Covid-19 crisis”, reports Deutsche Bank Research’s chief US economist. Matthew Luzzetti and colleagues in their 22 July note US Economic Perspectives – Minding the Fed’s policy gap. Deutsche Bank’s Jim Reid noted that the Fed’s balance sheet stood at US$7trn in early July, which was -3.5% below its peak at the start of June, but “this reflects emergency pandemic liquidity measures rolling off rather than anything more structural”.

He added that colleague Steve Zeng believed the figure was about to start climbing again, driven higher by renewed quantitative easing (QE) and various other loan facilities to around US$8.3trn by year-end, double where it was at the start of 2020, as per Figure 3.

Figure 3: Projection of the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet growth

Source : New York Fed, Deutsche Bank

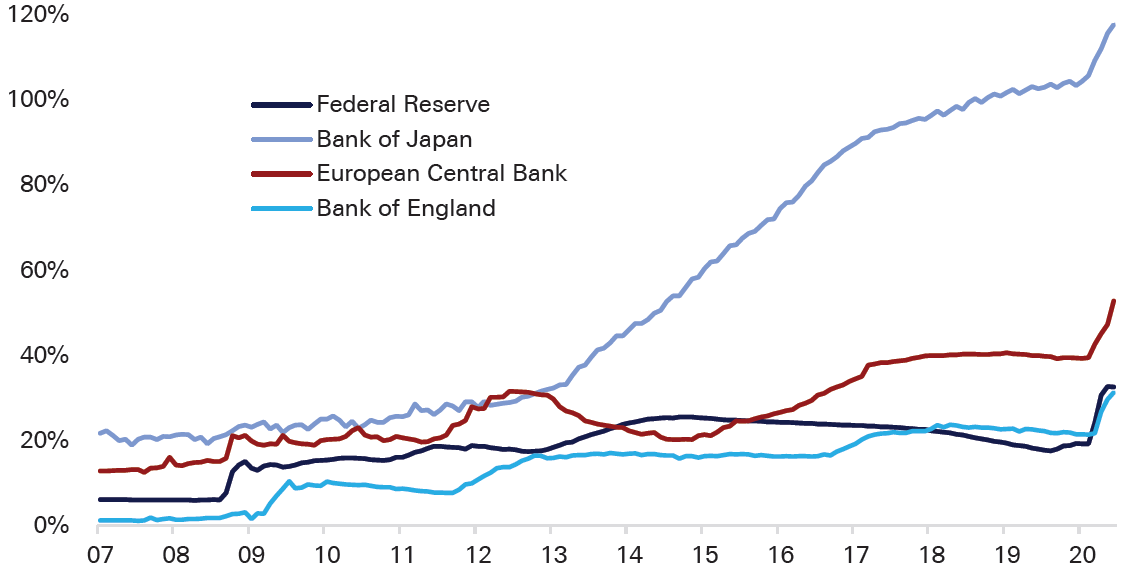

However, as Reid acknowledged, while many already regard this is a huge amount “the Fed’s balance sheet as a % of GDP is notably lower than the ECB and Bank of Japan’s (BoJ). If they were aligned, the Fed balance sheet would now be around US$11trn and US$25trn, respectively”, (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: Balance sheet as a % of GDP

Source: Bloomberg Finance LP, Deutsche Bank

In their 22 July paper, Luzzetti and colleagues comment that the initial stages of the Fed’s reaction to the pandemic can best be described as “firefighting”. “The Fed was focused on ensuring market functioning and preventing against the emergence of downside risks that can emanate from financial crises, [but] recent Fed communications have made clear that, having largely put out the metaphorical fires, the Committee will soon pivot their goal away from stabilisation and towards accommodation.”

The Federal Open Market Committee met this week on 28-29 July and at its previous meeting (9-10 June) FOMC officials were pessimistic about the ability of the US to rebound, Luzzetti and his team note. “The forecasts from nearly all officials at the June meeting anticipate the economy will not even approach full employment and 2% inflation – not to mention overshooting the 2% target, which many officials have discussed – by end-2022. Indeed, recent comments from some officials indicate that they are in the process of further marking down their outlook.”

The team concludes that only “massive” quantitative easing (QE) can close the policy gap. This means the Fed undertaking further total balance sheet expansion – on top of the increase of nearly US$3trn since the start of the Covid-19 crisis – by an additional US$5trn to US$12trn. “At the current pace of US$120bn of purchases per month (US$80bn of Treasuries and US$40bn of mortgage-backed securities (MBS)), the more optimistic scenario would take nearly four years to achieve, while the more pessimistic view would take more than eight years, assuming that all other assets remain unchanged, which will certainly not be the case as asset holdings in the Fed’s emergency credit and liquidity facilities roll off.”

Central banks

In our article, Central banks – on-side or outside (17 April) we summarised research demonstrating why temporary measures to tackle an economic emergency need to stay temporary and not become compounded into some sort of habit or “new normal”. The Economist takes this point further and remarks on “the state’s growing role of capital allocator-in-chief”, pointing to how “the Fed and Treasury are now backstopping 11% of America’s entire stock of business debt. Across the rich world, governments and central banks are following suit” (‘Free money’, 25 July). In other words, central bank independence seems a luxury from a past era.

The other point it brings out is how in the US, the UK the Eurozone and Japan central banks “have created new reserves of money worth US$3.7trn in 2020”. Much of this has been used to buy government debt, “meaning that central banks are tacitly financing the stimulus”. The result, says the newspaper, is that “long-term interest rates stay low even while public-debt issuance soars”.

UK: something’s got to give

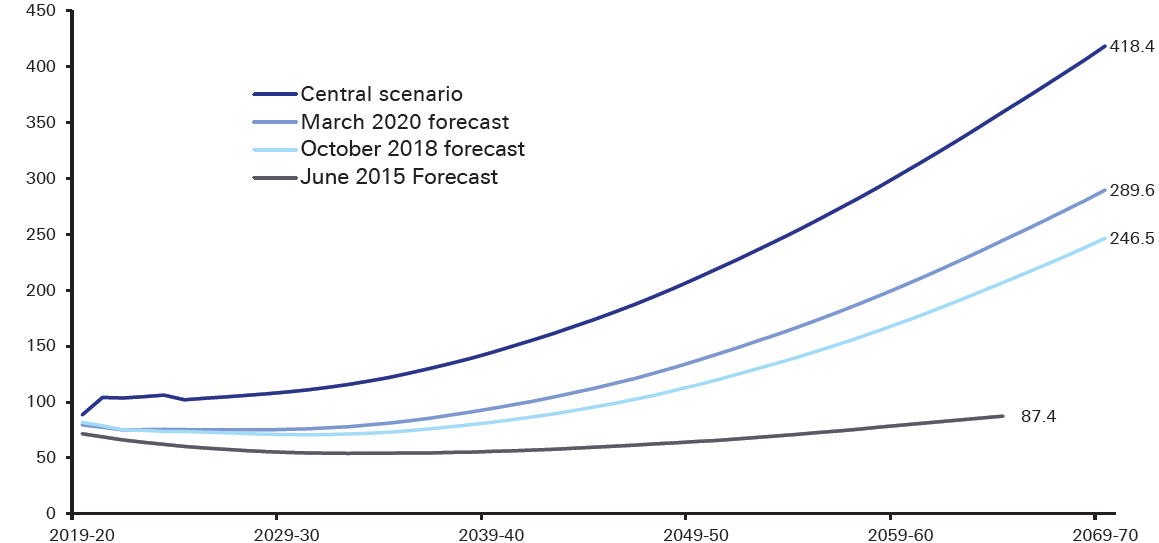

As Jim Reid and colleague Henry Allen noted in their 15 July research note Govt debt/GDP at over 400%?, this month UK fiscal watchdog the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) updated its assessment on the future path of UK public debt.

“Since Covid-19, their central scenario has shifted up considerably, now culminating in 2070 debt/GDP of 418%. By contrast, at peak austerity in 2015, debt/GDP was forecast at just 87% 50 years later,” they commented. “It shows how changes in assumptions can make major differences.” Figure 5 shows the respective forecasts:

Figure 5: OBR’s forecasts for UK long-term public sector net debt (% of GDP)

Source: OBR, Deutsche Bank

As Reid and Allen regard it as “almost inconceivable” the UK will ever reach that point “something will likely have to give” and as an ageing population is a major cause of its rising debt path this could well be “through an overhaul of spending on age-related areas (e.g. pension and healthcare costs). Alternatively, we could have to get used to higher taxes, inflation, more financial repression or the most unlikely scenario of all − default. Economic growth could bail us out but this will be tough given demographics”.

"Economic growth could bail us out but this will be tough given demographics"

What can probably be ruled out is a return to the long-term primary surpluses that the UK enjoyed over the century preceding the outbreak of the First World War in 1914. “Here the UK de-levered from circa.194% to 28% and ran primary surpluses in all but three years (1900-1902) around the Boer War,” they add, with an accompanying graph (Figure 6) dating back to 1689, when William III and Mary II ascended the throne as joint monarchs and five years before the establishment of the Bank of England.

Figure 6: UK central government primary surplus (% of GDP)

Source: Bank of England: Millenium of Macroeconomic Data, Deutsche Bank

Note: Using English GDP before 1700

“Democracies had yet to take shape at that point. In today’s world, politicians would struggle to get re-elected with such fiscal stringency,” says Reid (something Harold Macmillan was acutely aware of). “The road ahead is paved with debt across the globe. The solutions are not yet obvious!”

New era or tomorrow’s problem?

The sheer scale of the debt mountain and depth of the recession heralds something a re-set – the message The Economist leaves us with in its 25 July Briefing, having first walked the reader through the various stages of macroeconomic and policy-making evolution.

It’s likely that the state will play a much greater role in the economy from hereon, which will be welcomed by many economists, but it’s a policy not without risk. State interference in the natural economic order of things can have a tendency to prolong the problem – a point we made in Central Banks on-side or outside. As The Economist warns: “Governments which already carry heavy debts could decide that worrying about deficits is for wimps and that central-bank independence does not matter. That could at last unleash high inflation and provide a painful reminder of the benefits of the old regime.”

On the plus side, opportunities include aligning public investment with incentivising behaviour to reduce climate change impact (something that is gathering traction in the commercial lending sector).

However, as the IMF points out in Population 2020,1 “Population aging continues to displace population growth as the focal point of interest among global demographic phenomena.” For tomorrow’s taxpayers, the accumulation this particular debt mountain problem for future generations to sort out could not have come at a worse time.

Summary of Deutsche Bank Research reports referenced

Cross-Discipline Thematic Research – Fed Balance Sheet: One-way traffic again (13 July 2020) by Jim Reid and Henry Allen

Cross-Discipline Thematic Research – Govt debt/GDP at over 400%? (15 July 2020) by Jim Reid and Henry Allen

Focus Europe – EUR750bn EU Recovery Fund: Deal! (21 July 2020) by Kevin Koerner, Barbara Boettcher and Mark Wall

Focus Europe – Warning: Step back from the cliff edge (24 July 2020) by Mark Wall, Clemente Delucia, Michael Kirker, Marc de-Muizon and Sanjay Raja

US Economic Perspectives – Minding the Fed’s policy gap (22 July 2020) by Matthew Luzzetti, Brett Ryan and Justin Weidner

Go to Corporate Bank EXPLORE MORE

Find out more about products and services

Go to Corporate Bank Go to Corporate BankStay up-to-date with

Sign-up flow newsbites

Choose your preferred banking topics and we will send you updated emails based on your selection

Sign-up Sign-upSubscribe Subscribe to our magazine

flow magazine is published annually and can be read online and delivered to your door in print

You might be interested in

Macro and markets, Cash management, Trade finance and lending

Towards a silver lining Towards a silver lining

While the Covid-19 pandemic extends its grip, analysts are already assessing the impact and cost of what could be around US$5trn in fiscal support, and economies taking lessons from the global financial crisis

Cash management, Trade finance and lending, Macro and markets

GCC: four trends corporate treasurers should be aware of GCC: four trends corporate treasurers should be aware of

Digital transformation and infrastructure investment are top priorities in the Middle East as the region diversifies away from oil and gas. How does this impact the corporate treasury teams of companies operating in the region? flow’s Desirée Buchholz reports and shares two client examples from the Asia-Middle East corridor

Macro and markets, Trade finance and lending

No trade, no gain? No trade, no gain?

flow reflects on the seismic changes in the economic world order over the past 12 months, drawing on insights from the Deutsche Bank Research latest Outlook. The focus around inflation and rate cutting remains, centred on the scale of potential US tariffs following the decisive Republican victory on 5 November