29 April 2024

With the damaging effects of climate change and a rapidly rising population putting pressure on Tashkent’s ageing infrastructure, flow’s Clarissa Dann explores how Uzbekistan is modernising its historic capital’s water and sanitation systems

MINUTES min read

Tashkent, the largest city in Central Asia, is tucked away in the north-eastern region of double-landlocked Uzbekistan. It dates back at least 2,000 years and, having been destroyed by Genghis Khan in the 13th century, was successfully rebuilt by the Timurid Dynasty and transformed into a major trading centre on the historic ‘Silk Road’ – the network of Eurasian trade routes spanning more than 6,400km that first emerged in the second century BC and operated until the mid-15th century.

Flash forward to the present day and the Uzbek capital represents the economic and cultural heart of Central Asia, experiencing rapid demographic growth. By 1950, there were around 750,000 inhabitants. This has now risen to three million – a figure that is expected to rise to more than four million by 2050.1 Naturally, this growth has presented significant challenges, particularly in upgrading the city’s ageing water infrastructure, which dates to the 1960s. The systems providing the city’s population with clean drinking water and sanitation services are increasingly stretched.

These demands are likely to be further amplified as the population continues to increase. Recognising this, as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) reported in July 2022, the Uzbek government has identified access to water and the need to modernise infrastructure as a key priority for promoting economic development.2 Deutsche Bank Structured Export Finance team saw an opportunity to support this with a structured export finance-based package of lending.

Water under the bridge

In 1865, Uzbekistan became part of the Russian Empire and began to experience significant growth. Under Soviet Union control in the 20th century, the country’s infrastructure bore the hallmarks of socialist urban planning – stark, functional and monumental. Architecturally, Uzbekistan’s urban centres embraced expansive concrete structures and standardised apartment blocks in alignment with the communist ideals of functionality and utility. But, as historian Paul Stronski puts it in his book, Tashkent: forging a Soviet city 1930–1966, repeated ideological shifts and ever-changing political priorities hindered long-term planning and were major obstacles to urban renewal.

As part of these developments, and coupled with its rapid population growth, the country’s water and wastewater systems underwent substantial development during the Soviet era. Modernisation projects were put in place to ensure reliable water supply and sanitation services to the growing Uzbeki urban population, along with the establishment of water treatment plants and the expansion of sewage systems to manage wastewater.

By the time independence came in 1991, many of the water and wastewater facilities built during the Soviet era had aged poorly – and leaks, corrosion and other inefficiencies were becoming a major issue. Added to the need for extensive rehabilitation, the decentralisation of water supply and sanitation to local governments in 1996 proved a failure, with the resulting fragmentation and limited capacity contributing to high levels of pollution and contamination of Uzbekistan’s Zaravshan river and surrounding basin.3

While the politics, along with the country’s water infrastructure, have shifted and evolved over the years, the geographical reality of Uzbekistan as a landlocked country surrounded by five other landlocked countries remains – making access to water a logistical challenge. Virtually all the water resources in Central Asia come from the year-round snow and glaciers in Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan – and Uzbekistan too relies heavily on cross-boundary water from its upstream neighbours.4

Today, Uzbekistan’s unique geography – in combination with the heightening impact of climate change – means that the country is among the 25 most water-stressed countries according to the Water Resources Institute (WRI).5 These countries use more than 80% of their renewable water supply for irrigation, livestock, industry and domestic needs. “Even a short-term drought puts these places in danger of running out of water and sometimes prompts governments to shut off the taps,” says the WRI.6 This combination of factors has made improving the country’s water system a key priority for the government since the turn of the century.

For example, as part of the country’s ongoing efforts to improve its infrastructure, the government launched the Bukhara and Samarkand Sewerage Project (BSSP) in 2010 – an 11-year initiative to address a major source of the large-scale environmental pollution in the Zaravshan river basin: the widespread lack of wastewater treatment in two of the country’s urban centres, Bukhara and Samarkand. The development project, concluded in 2021, benefitted more than half a million Uzbekistanis with improved water supply and sanitation services.7

Plugging the leak in Tashkent

Despite some progress, 41% of Uzbekistan’s population still does not have access to safely managed water services and most households do not have access to centralised sewerage systems – not least in the country’s capital.8

To meet the rising demand for potable water and the need to ensure uninterrupted service around the clock for the city’s expanding population, Tashkent’s local authority was invited to seek the support of foreign companies to aid with modernisation efforts through the transfer of technology and expertise.

“We are delighted to support the Uzbek authorities in improving access to water services”

The move represented a concerted effort to introduce more modern and efficient forms of water management and strengthen the financial viability of the city’s existing operations. This assisted the aim of making Tashkent a pilot project for the broader modernisation of Uzbekistan’s water sector, as well as a showcase for the entire Central Asia region.

As part of these developments, the Municipality of Tashkent sought the support of France’s SUEZ Group (SUEZ), a provider of water and waste services with more than 160 years of experience in maintaining essential services that protect and improve people’s quality of life. In 2022, SUEZ provided drinking water to 68 million people, as well as sanitation services to 37 million people, across the world. “We are delighted to support the Uzbek authorities in improving access to water services for their population and contribute to local economic development with resilient and innovative solutions,” said Sabrina Soussan, Chairman and CEO of SUEZ when the deal was announced.

In June 2020, SUEZ won a seven-year project worth €142m with the Municipality of Tashkent, the Ministry of Construction, Housing and Communal Services and the national water company and network owner Tashkent Shahar Suv Tamnoti (TSST),with the operator Uzsuvtaminot to jointly implement a tailor-made action plan: the Tashkent Water Transformation Plan (TWTP).9 On 22 November, 2022, SUEZ signed landmark agreements with its Uzbekistan partners,10 and the seven-year action plan finally commenced in August 2023,11 consisting of three phases:

- Baseline phase (15 months). During this time, equipment programmes will be launched and various indicators and targets (including water quality, water losses and collection rates) will be monitored.

- Phase 1 (21 months). This phase will see the deployment of the entire TWTP. KPIs will be monitored throughout.

- Phase 2 (48 months). A portion of SUEZ’s remuneration (5% per annum) will be conditional on the achievement of operational objectives, measured through the contractual KPIs.

“This modernisation project is strategically important to the infrastructure in Tashkent”

The jointly-managed contract relies on the close monitoring of performance and technical excellence, as well as an action plan to improve the quality of drinking water, reduce non-revenue water (e.g. water that has been produced and is "lost" before it reaches the customer) by 12% and increase the collection rate in order to achieve financial stability.12 To achieve these goals, the action plan sets out several key objectives:

- Improve the day-to-day management of water demand and supply. This will be achieved through the implementation of an intelligent management tool connected to a real-time supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA) monitoring system, meaning that 100% of the network’s geographic information systems (GIS) are digitised and monitored in real-time.

- A reduction in water losses. The implementation of the SUEZ diagnostic tool will help maintain the highest international standards. The tool is dedicated to loss analysis and uses advanced leak detection technology and repair techniques to maintain operations. By identifying 30,000 leaks using innovative methods, it will reduce water abstraction by 33 million m3 per year by the end of the project, equivalent to the annual consumption of an Uzbek town of 330,000 inhabitants.

- Implement the latest digital solutions. A new Operations Centre will use smart decision-making tools to enable water and energy consumption reductions that will preserve resources and prioritise investments, while the installation of 650,000 smart meters will allow accurate billing. This will also contribute to reducing the city's overall water consumption, helping it to meet the challenges of water scarcity in the context of global warming.

- A focus on the future. By educating thousands of local water professionals, mostly made up of TSST staff, the SUEZ water academy in Tashkent will train the next generation of Uzbek managers and water specialists (4,000+ people trained, 15,000+ days of training, 1,500+ days of technical assistance). And through the introduction of both a performance plan and a 20-year master plan that identifies priority investments, the project aims to ensure the long-term sustainability and excellence of water infrastructure, while rapidly improving TSST’s financial situation.

Financing the transformation plan

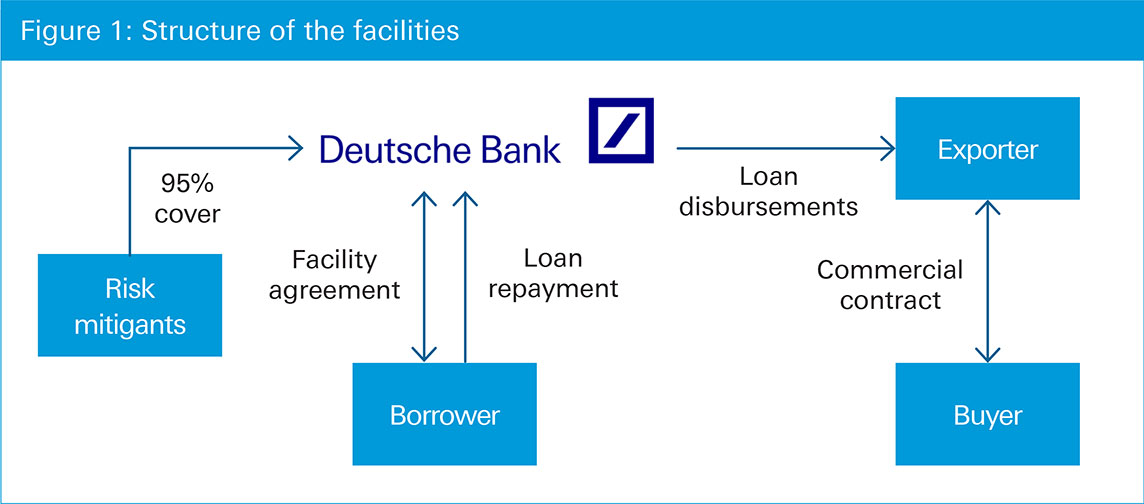

Figure 1: Structure of the facilities

The financing package consisted of a two-tranche Bpifrance Assurance Export (BPIAE)-covered buyer’s credit facility for €109.5m, with 13- and 17-year tenors, financing the eligible portions of the export contract value plus the BPIAE premium. There is also a five-year tied commercial facility totalling approximately €22.23m that will be used to finance the down payment due under the commercial contract, and approximately €1m worth of goods and services not eligible for BPIAE support. The financing package also includes a €30m direct loan from the French Treasury. Together, the three facilities finance 100% of the project costs.

By way of support, Deutsche Bank acted as mandated lead arranger, agent and lender, and signed BPIAE supported and commercial facilities for the financing of the TWTP (see Figure 1). The loan fits with United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 6 – Clean Water and Sanitation – and has contributed to the bank’s ambitious ESG target.

“This modernisation project is strategically important to the infrastructure in Tashkent, as well as its people. We are delighted to have leveraged our experience working on mixed financing structures to play a role in making this ambitious project a reality,” reflects Vincent Gabrie, Head of Structured Trade and Export Finance, France at Deutsche Bank.

Sources

1 See sites.ontariotechu.ca

2 See aiib.org

3 See worldbank.org

4 See aiib.org

5 See wri.org

6 See aiib.org

7 See worldbank.org

8 See aiib.org

9 See smartwatermagazine.com

10 See smartwatermagazine.com

11 See suez.com

12 See suez.com