9 October 2024

Following flow coverage of collateralised loan obligations (CLOs) and trade finance assets from an origination and investor perspective, the flow team reviews private credit, an asset class which has grown significantly since the financial crisis. This ‘explainer’ includes an overview of the sector’s asset managers, borrowers, financing structures, geographies, investor capital, and product offerings

MINUTES min read

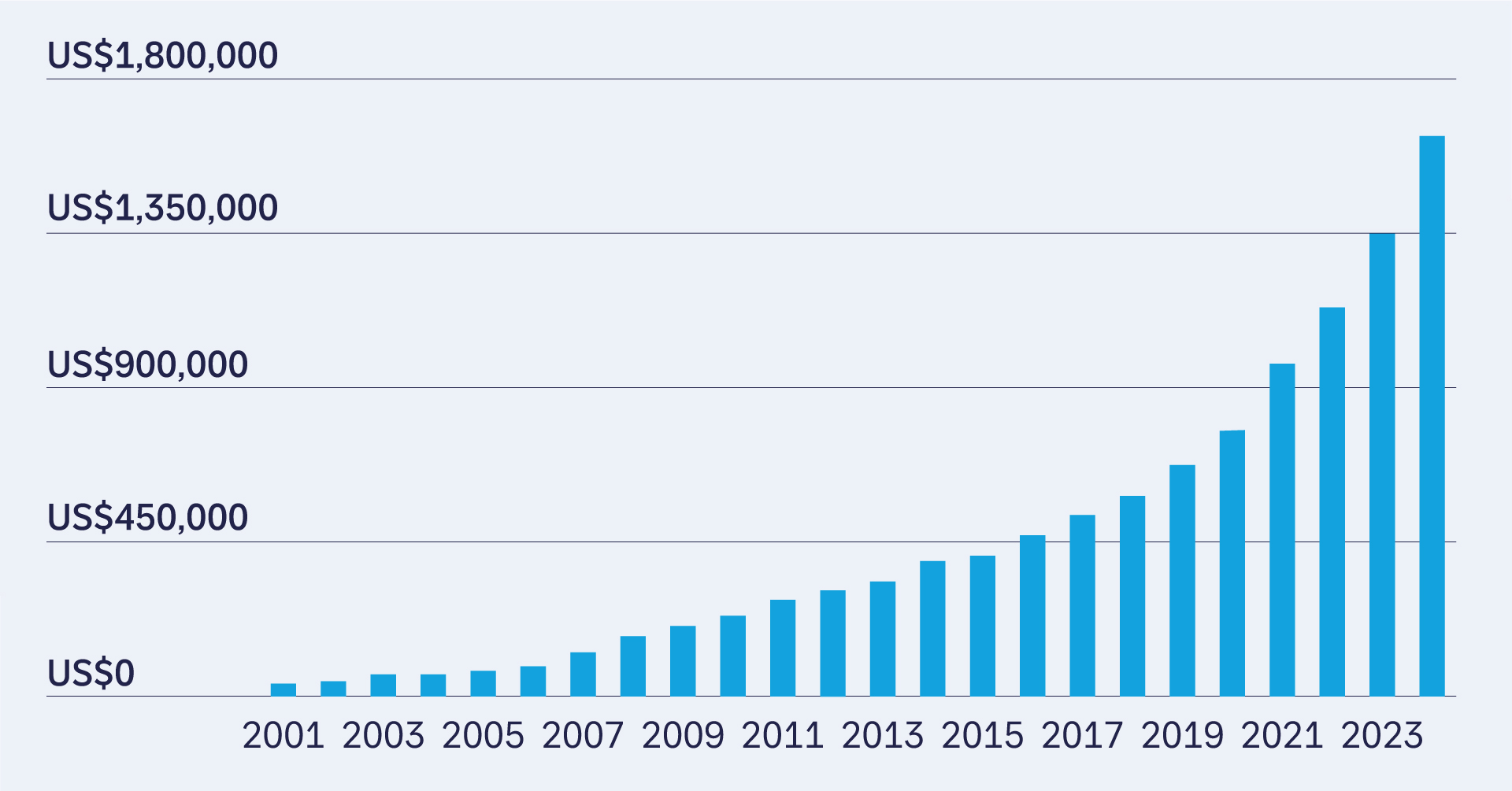

By the end of 2023, the total of private debt assets under management had reached US$1.62trn – up 17% on 2022 with a pattern of meteoric growth over the past 23 years (see Figures 1 and 2) according to Preqin, the investment data managers.

In January 2024, the Bank of England estimated a four-fold rise to around US$1.8trn since 2015. “Given the limited data available the true market size could be much larger,” commented Lee Foulger, Director of Financial Stability, Strategy and Risk at the UK central bank in his lecture, Non-bank risks, financial stability and the role of private credit. According to Foulger, much of the growth had been sustained during a period of low interest rates when borrowing costs were low- and fixed-income investors were in search of yield.1

But what is private credit and why are investors attracted to it?

Figure 1: Total private debt 2000 to 2024 (US$m)

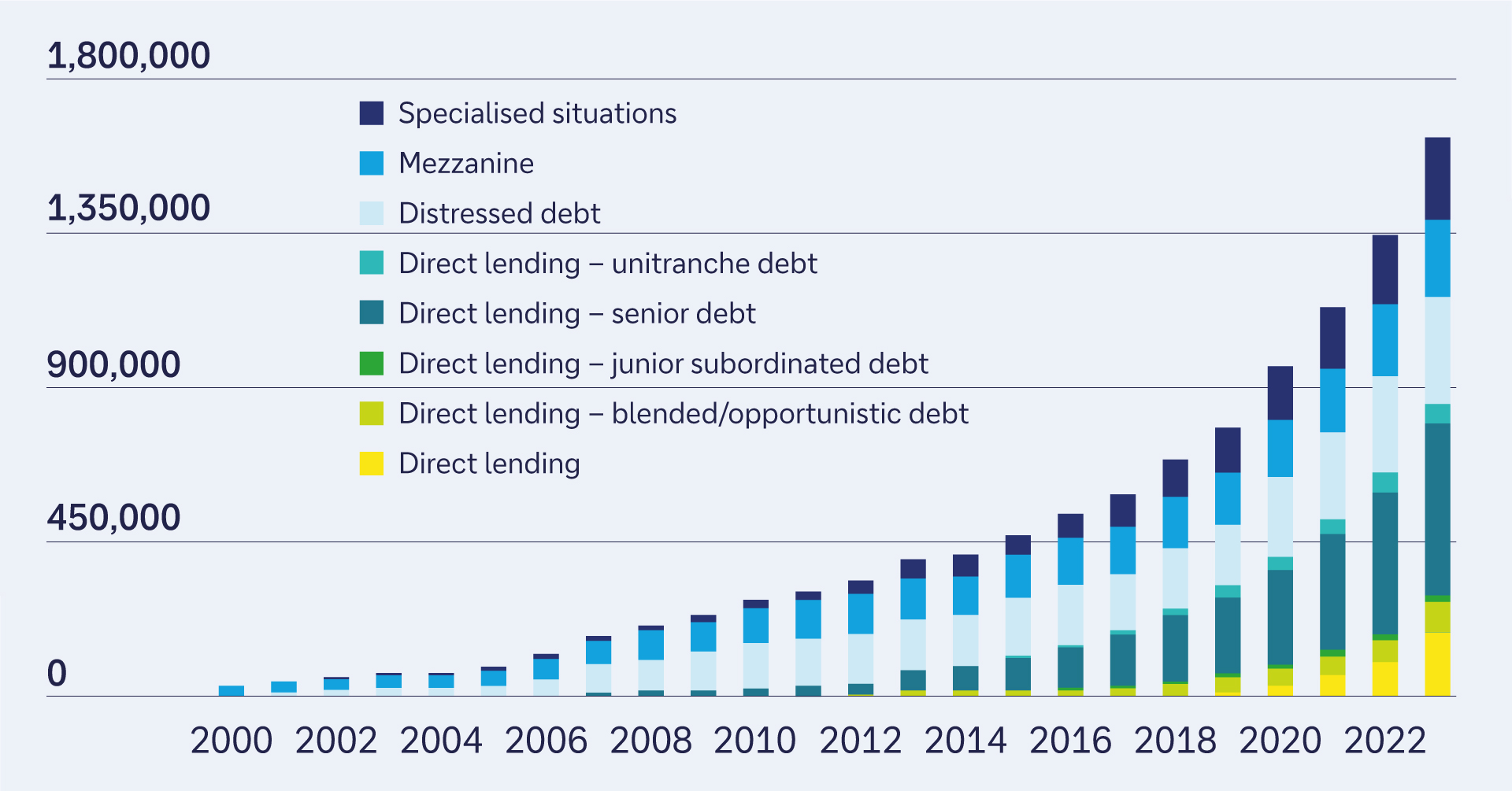

Figure 2: Components of private debt 2000 to 2024 (US$m)

Source Preqin

Characteristics of private credit

Private credit is non-bank lending typically to middle market companies which typically range in size from US$25m to US$75m in EBITDA. These companies can either be sponsored, or owned by a private equity firm, or non-sponsored. They are also often unrated companies, although a credit assessment, or point-in-time rating of the company will often be done in conjunction with financing. The term ‘direct lending’ is synonymously used with private credit, capturing the direct nature of the financing process which foregoes needing an arranging bank as an intermediary – thus, financing is directly negotiated between a single, or small group of lenders, and the borrower.

A few additional characteristics help define private lending:

- Financing is typically floating rate in nature (over the Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR), meaning that the interest which needs to be paid by the borrower will fluctuate with interest rates. The borrowers have traditionally been small-to-mid-sized private companies with a credit assessment of B-; however, larger companies are increasingly tapping the private credit market, with a credit rating of B or higher. The ticket sizes have grown larger recently as larger private credit funds have been raised and able to deploy more capital to borrowers.

- The financing typically spans a range between US$10m–250m for a three to seven-year term loan. What was typically a one-lender to one-borrower relationship has grown into a small group of lenders that are able to pool financing together. This has brought the upper bound of ticket sizes to US$5bn+, and therefore mirroring the size of large public market transactions and blurring the lines to some extent between the public and private credit.

- Financing terms can be as high as 400bps above the lending rate for a publicly funded transaction. This large spread differential is partly the result of an “illiquidity” premium attached to the debt, which does not trade on the secondary market and is therefore used to compensate an investor for the increased risk of not being able to unload an asset during a period of market stress. This spread pick-up, however, is one of the most attractive aspects to the asset class for both investors and private credit managers and was one of the driving forces to private credit’s ascent following the low interest rate and broadly constructive macro backdrop post Global Financial Crisis (GFC).

- The deal terms for a private credit transaction are typically “covenant heavy”, meaning that the deal documentation includes provisions meant to offer downside protection for lenders, such as the company needing to maintain specified thresholds for liquidity and leverage. Covenant-rich documents are a point of departure from the public market syndicate financing, which have typically been “cove-lite” following the resurgence of the leveraged loan market in 2011 post GFC.

“With a pull-back from arranging banks, private credit funds could establish market share during a period of heightened market volatility”

Where private equity comes in

The relationship between private credit and private equity (PE) is synergistic – to help finance a leveraged buyout or acquisition, a PE firm will seek additional financing. Traditionally, leveraged buyouts (LBOs) and mergers and acquisitions (M&A) activity has been provided by the public market, with arranging banks bringing a deal to market and providing the initial financing before syndicating the debt to a group of investors. But deal activity began to bifurcate towards private credit during 2022, the result of a few high-profile deals being ‘hung’ or left on the balance sheets of arranging banks as investors shied away from the market due to a rapid rise in interest rates from the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC)2 that put downward pressure on loan prices. “With a pull-back by arranging banks, private credit funds could establish market share during a period of heightened market volatility, and although interest rates have begun compressing in both the US and in Europe, LBO financing will likely be a blend between the private and public markets,” explains David C West, Global Head of CLO Product Strategy, at Deutsche Bank.

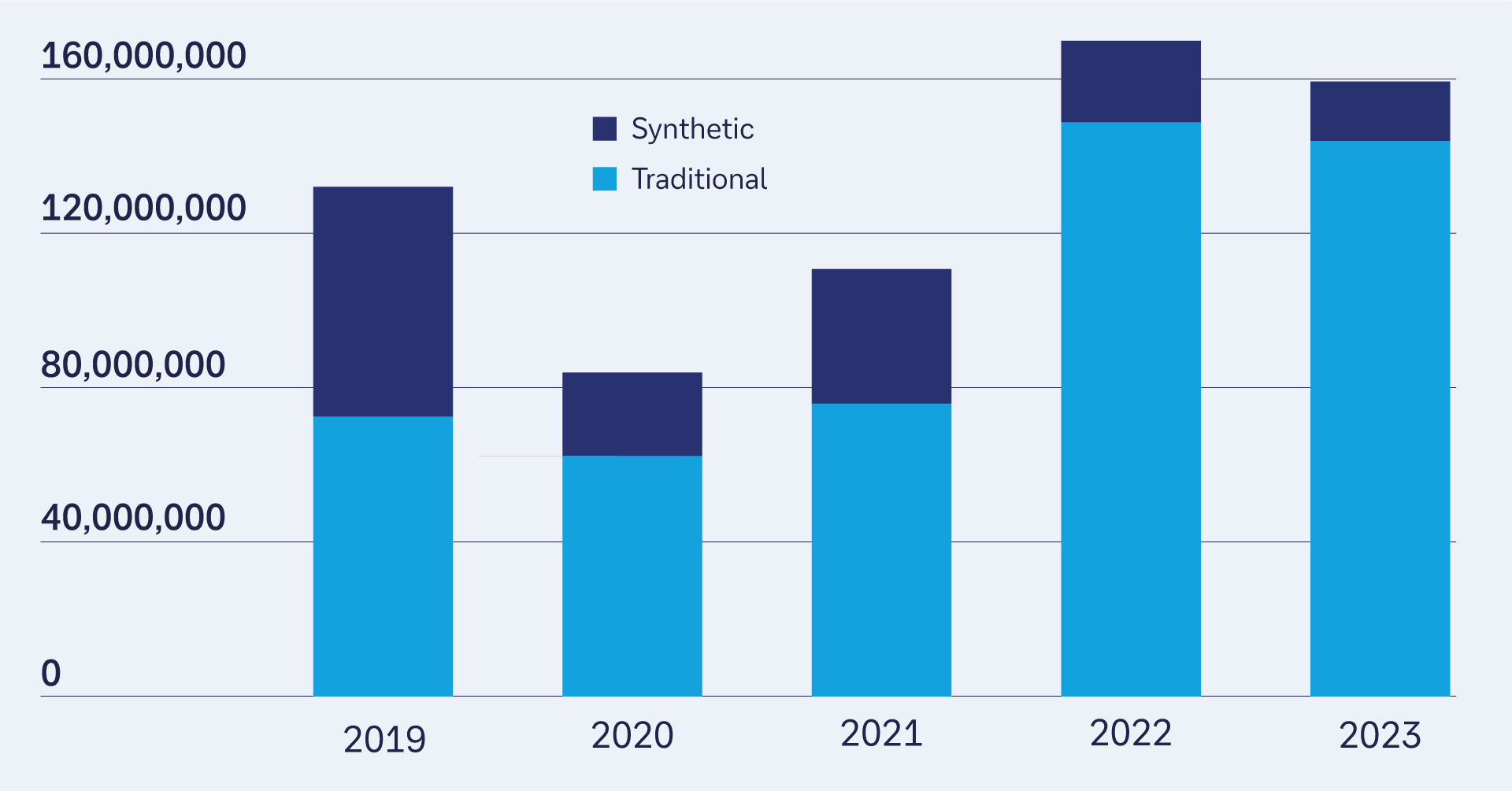

And increasingly, the relationship between banks and private credit is also becoming synergistic. Although most private credit transactions are ‘unitranche’, meaning that the first lien senior-secured and second lien (more junior) portions of a transaction are typically bundled and financed by the same lender (or small pool of lenders), banks are increasingly providing first-lien financing for private transactions and sourcing the second lien, or riskier and wider-spread yielding part of the debt to a private credit manager. This can be structured as a synthetic risk transfer (SRT), which enables a bank to compete in the direct lending space while unloading the riskiest part of the notes (transferring the risk) to private credit funds and other investors.

“SRTs have seen greater market adoption in Europe so far than in the US – in 2023, the deal volume of SRT transactions with performing loans was roughly €155bn, with synthetic transactions taking the bulk of the volume compared to cash transactions”, noted Deutsche Bank Research CLO strategists Conor O’Toole and Jamie Flannick in US CLO Weekly The knock-on effects of tightened regulation and high interest rates on 24 June 2024 (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: SRT market size, Europe – transactions with performing loans

Source: Deutsche Bank Research

Deutsche Bank has been an early mover in this space and has a robust SRT business in Europe which is being scaled in the US. Thus, SRTs have increasingly become intertwined with the private credit market as banks scale their direct lending efforts while balancing the risk-based capital charges stemming from prudential regulation such as Basel 3.3

Private credit is often associated with corporate direct lending. However, the broader category of private debt is rapidly branching into other segments of the capital markets and now includes asset-based financing (ABF) – the private financing of hard assets, such as data centres and infrastructure projects. When considering these additional adjacencies, the private debt market size is more like US$3trn and set for exponential growth going forward.

Growth of the asset class

Banking regulatory trends post GFC have increased the cost of capital for riskier assets, such as leveraged finance lending. This incentivised banks to focus more on the arranging, rather than the on-balance sheet holding of certain assets, providing an onramp for direct lenders to step forward while the banks pulled back. This was illustrated during the March 2023 US banking crisis,4 further strengthening the call to raise barriers to lending due to liquidity needs. Banks restructured default risk exposures on pools of loans with the issuance of notes linked to the credit pool or via a special purpose vehicle (SPV) to private credit managers, and non-bank providers stepped up.

In a helpful explanatory article ‘Private credit: Characteristics and Risks’ published by the Federal Reserve on 23 February 2024, the authors note, “There is growing concern that tighter regulations such as Basel III endgame could intensify migration of credit from banks to private credit lenders. Considering borrower risk profiles, such substitution is less likely to occur to bank-held loans, and more so with syndicated leveraged loans. In such cases, banks stand to lose underwriting fees to private credit funds. These developments suggest that private credit will become increasingly important to credit market functioning.”5

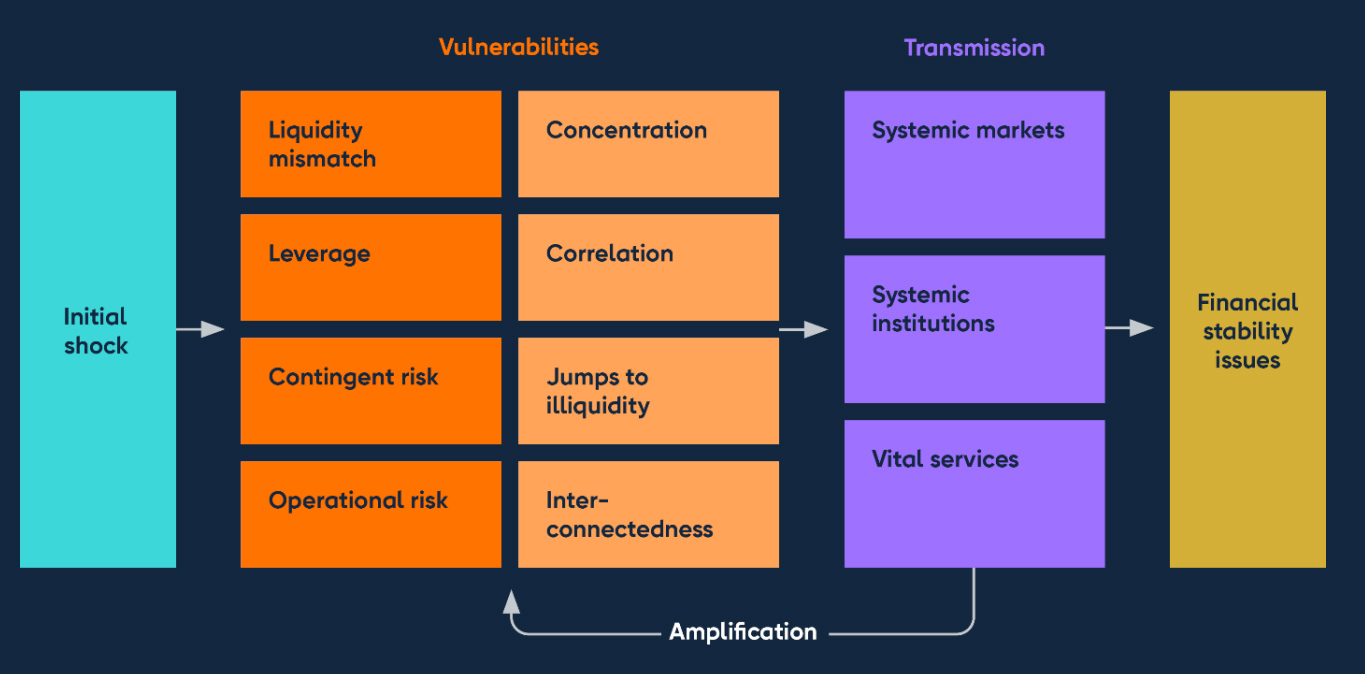

While Bank of England’s Lee Foulger underlined the wide financial stability picture in his January 2024 lecture and put the source of finance the context of other funding sources (see Figure 4), he said, “The availability of private credit can be beneficial for economic activity and innovation. By providing finance where traditional means fall short, it can support investment and growth opportunities. And to the extent that private credit substitutes for bank financing, it can contribute to the diversification of financing sources. In many ways lending via private markets is likely to be lower risk from a financial stability perspective than had the lending been undertaken by the pre-GFC banking system.”

Figure 4: Highly leveraged corporates are reliant on a variety of funding sources, including from private credit, private equity and leveraged loans

Source: Bank of England

It is often the most viable financing solution for many corporates. Borrowers appreciate the flexibility of private credit, which allows them to use it for expansion, refinancing, and improving working capital. Benefits include better servicing, and an increased number of providers, including one-stop shops such as private equity (PE) houses. Private credit typically also features more ‘bullet payments', allowing borrowers to invest in growth rather than meeting immediate repayment obligations.

Investor demand for the resulting debt asset is primarily institutional, but retail flows are increasing due to the greater use of the BDC (Business Development Company) structure. Private credit offers compelling performance metrics, such as senior lending returning almost 9% annually over the last decade, which is greater than that for global equities and double that for publicly traded loans.

Private credit assets also offer investors:

- Low correlation with public markets;

- Current income through interest payments and fees. This is dramatically different from an investment in private pquity, which has a lock-up period typically of 8–10 years before capital is returned to an investor;

- An illiquidity premium (investors can pocket the yield spread, often around 250 bps of yield per annum above leveraged loans; and

- Potential for portfolio customisation through use of various private credit strategies.

Investors are boosting their investment in direct lending due to its lower volatility, higher yields, and superior risk-adjusted returns over public debt. The Cliffwater Direct Lending Index recorded 12% total returns in 2023,6 with one bank predicting annual returns of 8.5%+ for the next decade.7 Private credit's resilience has been confirmed, with average returns of 11.6% across seven periods of high interest rates between 2008 and 2023, and losses during the Covid-19 pandemic at half that of high-yield bonds.8

In short, private credit offers investors increased exposure to corporates and sectors, increased flexibility in capital use, increased opportunities to collaborate with borrowers on ESG matters or in work-outs, increased resilience, and increased risk-adjusted returns.

Competitive landscape

All private credit managers compete on the same variables: finding and agreeing the loan (origination), doing so quickly and flexibly, and providing integrated banking services. Another commonality is average hold times of three years, so the deal funnel must also be a constant focus. However, given the variety of players, and mix of specialisms, the competitive landscape for private credit can be categorised according to ticket size and risk:

- Core middle market providers compete to simplify borrowing for sponsors to secure multiple unitranche (or ‘hybrid’) deals – these being single-tranches with blended senior/junior rates.

- Upper middle market providers are typically larger, and their deals are fewer but bigger than the core; they compete with the Broadly Syndicated Loan (BSL) lenders.

- Lower middle market providers used to specialise in lower-risk senior debt but are increasingly moving upwards into the core middle market. Global banks compete for high-end marquee sponsors, but also reach down into the market.

- Niche or regional banks compete for senior direct lending to non-sponsored corporates.

- Opportunistic specialists seek situations for workouts on loan-to-own deals and/or spread pick-up on distressed deals.

Credit selection is, of course, critical for private credit managers, who conduct rigorous due diligence – with many having specialist sector knowledge to identify important characteristics of the debt. Retail investors will shortly have access to asset class via exchange traded funds (ETFs). “This is a large growth vector and is where the competitive dynamics are likely to head,” said Deutsche Bank Research’s Flannick.

Role of banks in private credit

Traditional banks remain vital components of the private credit market due to their expertise and capabilities, including teams focusing on origination, work-out, cash management, treasury, back-office and IT infrastructure. Private equity sponsors (who back up to 80% of deals) and their portfolio companies alike rely on these banking services – such as FX hedging, research, and risk management and transfer. Full-service investment banks such as Deutsche Bank's Trust & Agency Services (TAS) team can serve as a conduit to new customers and new customer segments that traditionally have not invested in private credit. These could range from regional insurance companies which have lacked the right partnership to enter the market and deploy capital. Or, it could be via the high-net worth or family office segment, often aligned to an investment bank’s wealth management arm. And, increasingly, it could be via relationships with sovereign wealth funds, which have capital to deploy and likely have touchpoints with large global footprint investment banks.

“The strategic positioning between [banks and private credit lenders] seems to be increasingly aligned as the market further evolves”

“Although the relationship between banks and private credit lenders has often been portrayed as contentious, the strategic positioning between both seems to be increasingly aligned as the market further evolves. Points of direct competition will also likely remain and potentially even intensify as well, however, around some core operations. But increasingly, a constructive equilibrium seems to be within reach,” observed Deutsche Bank Research’s O’ Toole and Flannick their note, US CLOs: Finding a constructive equilibrium (1 July 2024).

Banks themselves are moving directly into private credit, both by using their balance sheets, forming BDCs, or marshalling resources through other means such as commingled funds, separately managed accounts, or establishing other managed funds. Bank entry into this space can be via organic growth, strategic alliances, or outright acquisition of teams from competitors. For example, in September 2023, Deutsche Bank established Deutsche Bank Investment Partners (DBIP) that provides private credit investment opportunities to bank clients.9

Outlook for growth

Private credit segments forecast to be growth areas include:

- The longer-term trend of extending credit to high-quality growth companies;

- Junior capital and hybrid (i.e. unitranche) deals (if interest rates remain higher for longer);

- Rescue financing (if ‘higher for longer’10 interest rates cause a recession and higher defaults); and

- ETFs. As highlighted by Deutsche Bank’s Flannick, these will “unlock access to a relatively untapped market (the retail investor) as well as possibly mitigating some of the liquidity challenges associated with retail BDCs”. He explains that ETFs “may enable large asset managers to sidestep some of the potential liquidity challenges that BDCs face during periods of market dislocation due to the larger retail investor adoption of the ETF vehicle and the likelihood of trading to continue even during periods of market stress”.

Higher interest rates mean ratio tests start to become a challenge – less so for B-rated corporate issuers (the mainstays of the BSL and high-yield markets) but more so for CCC-rated corporates whose cash flows might now prove insufficient. This is where private credit’s speed and flexibility can help. New financing structures likely to grow include preferred equity, paid-in-kind (PIK) notes, and net-asset value (NAV) facilities and these are useful for fund financing deals; a reminder that cashflow challenges are not limited to corporates, as managers’ funds can also face difficulties due to muted IPO and M&A activity. Private equity, historically using subscription lines with banks, has become reliant on such NAV-lending strategies due to banks withdrawing from the space.

With investors also keen to have ready access to their capital, managers will likely develop private credit-specific secondary trading platforms. Such flexibility will itself only further increase investor appetite for private credit. With more borrowers, investors, sophisticated managers and banks servicing the private credit ecosystem, the future looks bright.

As Jon Aisbitt, Chairman of DBIP said at its launch, “Investor and borrower demand for private credit solutions continues to grow. Deutsche Bank has a strong track record in the space and the senior Deutsche Bank Investment Partners team has a wealth of investment experience through the cycle and across asset classes”.11 While a win-win for all, the biggest beneficiaries are end-user corporates who, rather than having to turn to private credit because they had no other choice, now have the choice to raise debt according to the best terms available to them whether in the public or private credit markets.

Deutsche Bank Research reports referenced

US CLO Weekly: The knock-on effects of tightened regulation and high interest rates by Conor O’ Toole and Jamie Flannick, Deutsche Bank Research (24 June 2024)

US CLO Weekly: Finding a constructive equilibrium by Conor O’ Toole and Jamie Flannick, Deutsche Bank Research (1 July 2024)

Sources

1 See bankofengland.co.uk

2 See "Monetary policy relaxation?" at flow.db.com

3 See also US CLO Weekly: The knock-on effects of tightened regulation and high interest rates by Conor O’ Toole and Jamie Flannick, Deutsche Bank Research (24 June 2024)

4 See edition.cnn.com

5 See federalreserve.gov

6 See cliffwaterdirectlendingindex

7 See privatebank.jpmorgan.com

8 See morganstanley.com

9 See db.com

10 See "What impact is “higher for longer” having on the CLO market in 2024?" at flow.db.com

11 ibd