26 April 2023

At a time when crises and ‘unprecedented events’ seem to have become the norm, Helen Sanders assesses the value of cash flow forecasting when the future is impossible to predict, and considers what the alternative might be

More than a year since the onset of the Russia/Ukraine crisis, the geopolitical and macroeconomic landscape looks more uncertain than ever – with the widespread return of inflation adding further obstacles to growth.

Company boards, together with the corporate treasurers and chief financial officers who support them, are rethinking how they design and deliver on a future proof corporate strategy. Their aims are both to build adaptability and resilience to the next crisis that emerges, while keeping a readiness to adapt to new opportunities that arise.

The Russia/Ukraine crisis has had both immediate and longer-term implications. Russia is the world’s 11th largest economy1 so international sanctions meant that thousands of companies with activities in or with the country were forced to adapt their business at pace. Ukraine, Europe’s largest country geographically, plays a critical role internationally in the agricultural, metallurgy, minerals, chemicals and timber industries. The war has created significant supply, and supply chain issues. Furthermore, the effect on energy prices and inflation has triggered both a cost-of-living crisis and major social and economic ramifications in many countries.

The predictability of the unpredictable

Just as the conflict in Ukraine came in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic, the earthquake that struck southern and central Turkey and northern and Western Syria on 6 February 2023 demonstrates how ‘Black Swan’ events (those that cannot be predicted in advance but have a high impact) have become a fact of life – including corporate life.

In many respects, companies have already become adept at managing crises, as they evidenced in their responses to the pandemic.2 However, the pace at which crises have occurred and unfolded in recent years has been relentless. Many companies have been focused on dealing with the immediate needs created by the current crisis or crises, without the space to think about how they should position their strategy and operations to become more resilient and adaptable to manage future ones.

As early as 2009, authors of the Harvard Business Review noted that Black Swan events were becoming more frequent3, as were ‘grey rhino’ occurrences – foreseeable events but whose timing and impact are unclear. However, as the HBR article warned, “Risk managers mistakenly use hindsight as foresight. Alas, our research shows that past events don’t bear any relation to future shocks.”

Furthermore, risk memories are short. Covid-19 was treated as a black swan event by most organisations, yet the experiences of Spanish influenza, Ebola and Zika and others, all which all occurred within a 100-year period, suggests organisations might have expected to be charged by a Covid-infected grey rhino at some point.

Treasury’s role in crisis planning

Treasurers are at the heart of risk planning for their organisations, most notably in market, credit and liquidity risk. Although market risk and credit risk can have an enormous impact on financial performance, companies often have levers to mitigate them, although the costs may be high.

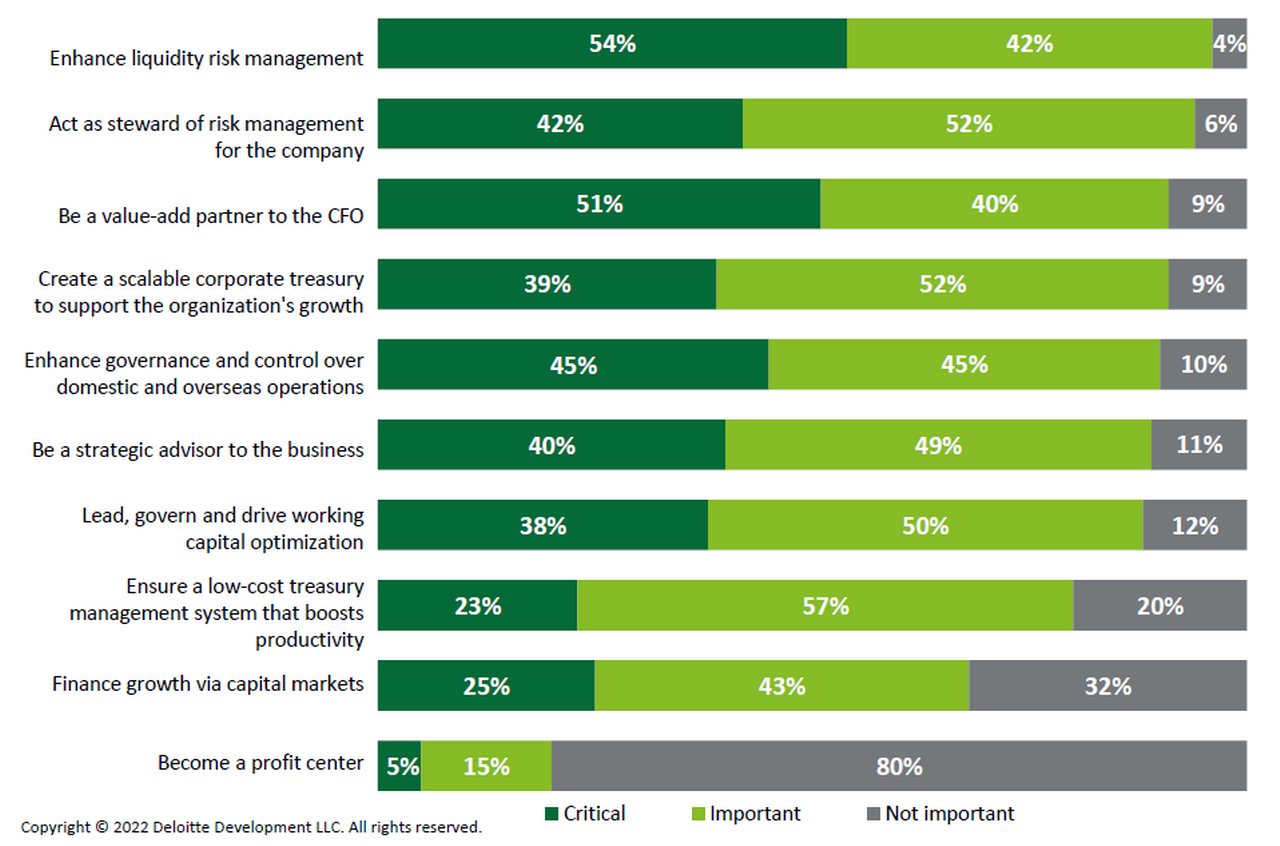

Figure 1: Top mandates defined for the treasury function

Note: this survey was based on 245 interviews conducted across Deloitte’s global network via a questionnaire

By contrast, liquidity risk is often a far greater challenge. According to Deloitte’s 2022 Global Treasury Survey (see Figure 1)4, managing liquidity risk is the most important element of treasury’s mandate, with 96% of treasurers noting its importance and more than half emphasising that it is critical. In the same report, 56% of treasurers – the highest proportion in this survey – placed liquidity management in their top three priorities for 2023. The second most cited issue in this priority list for 2023 was cash flow forecasting (41%). Given the close connection between cash flow forecasting and liquidity management and planning, the survey illustrates the critical importance of these issues for treasurers.

To manage and plan liquidity effectively, companies have traditionally relied on cash flow forecasting to understand where, when and in what currency liquidity squeezes or surpluses are likely to occur. This is not a new nor unfamiliar requirement: cash flow forecasting has routinely appeared at or near the top of treasurers’ list of priorities – but also challenges – over the past decade or more.

The difficulties in creating accurate and timely cash flow forecasts are manifold. Fragmented and inconsistent data, often created in multiple locations and formats; delays in consolidating information; and problems with using historic data to predict future cash and liquidity positions are amongst the most prevalent. A common technology platform, and consistent policies and processes help address the issue of data fragmentation, inconsistency and delay – as many articles and podcasts outline. Most recently former Salesforce Treasurer Ed Barrie said in a Treasury Management International (TMI) podcast, “Best-in-class treasury departments are … centres of excellence for data analytics for their organisations, and cash flow forecasting is the intersection of data and analytics.”5 Such analyses often build in factors such as seasonality, weather, energy prices and inflation, and volatility in the cost of inputs to increase accuracy. Others use artificial intelligence (AI) to model future cash and liquidity positions.

Has forecasting become obsolete?

These forecasts can be useful, even essential, for managing cash and liquidity in a ‘business as usual’ scenario. However, as was noted earlier ‘past events don’t bear any relation to future shocks.’ As the Harvard Business Review comments, “There are typical heights and weights, but there’s no such thing as a typical victory or catastrophe. We have to predict both an event and its magnitude, which is tough because impacts aren’t typical in complex systems.”

“The imperative to lift one’s gaze and look around the corner has become key to strategy and performance”

The pandemic was a case in point. While companies could – and did – factor in supply chain disruption, the massive and rapid shift in consumer behaviour was far more difficult to predict. Consequently, to prepare for the inevitable black swans and grey rhinos ahead, as a recent McKinsey report emphasised, “The imperative to lift one’s gaze and look around the corner has become key to strategy and performance—scenario planning is squarely back.”6

Scenario planning is a separate, albeit complementary process to cash flow forecasting. This is already familiar to treasurers planning acquisitions and modelling the impact of changes to tax rates, regulations, input costs etc. It also plays an essential role in crisis planning. It is impossible to anticipate and plan for every possible scenario. But company boards increasingly rely on treasurers and their colleagues across the business to identify the geopolitical, economic, environmental/climate-related, digital or supply chain scenarios that would have the greatest impact– whether positive or negative – on their business. Having done so, they can model the financial, operational, employee and customer impact, and consider any contingency planning. In each case, they might explore the base case (most likely or ‘average’ scenario based on most likely impact), best case and worst-case outcomes.

“Treasurers who forecast effectively are able to make better investment and liquidity management decisions”

In 2009, the authors of the Harvard Business Review article cited earlier commented, “You often hear risk managers—particularly those employed in the financial services industry—use the excuse ‘This is unprecedented’. They assume that if they try hard enough, they can find precedents for anything and predict everything. But Black Swan events don’t have precedents. In addition, today’s world doesn’t resemble the past; both interdependencies and nonlinearities have increased.” This point was developed by Deutsche Bank’s Thomas Mayer, Head Cash Sales GY/CH/A & EMEA Head Investment Solutions at Deutsche Bank in a January 2023 commentary, which noted “Covid-19, the flight to liquidity, and the effects of supply chain disruption and geopolitical challenges were unprecedented, so treasurers are accustomed to dealing with uncertainty.”7

Zorawar Singh, Global Head of Off-Balance Sheet Investments, Cash Management at Deutsche Bank makes the point that “treasurers who forecast effectively are able to make better investment and liquidity management decisions in terms of the working capital facilities they need, and the types of investments they can undertake”.

“Recent stresses have caused treasurers to adopt a wider investment toolkit, such as money market funds, repos, government bonds as safe and liquid investments to complement their bank deposit exposure,” he explains.

Liquidity impact testing

Treasurers might not be the ones modelling supply shortages and demand shocks, but they are uniquely equipped to assess the impact on liquidity, the lifeblood of the business. Through better scenario modelling and planning, in co-operation with the wider business, treasurers can help the business through good times and bad.

Helen Sanders is a consultant to the financial services sector, the former Director of Education at the ACT and was Editor of Treasury Management International from 2006 to 2018

Sources

1 See investopedia.com

2 See "From the engine room" at flow.db.com

3 See hbr.org

4 See deloitte.com

5 See treasury-management.com

6 See mckinsey.com

7 See "Are treasurers’ investment priorities shifting as interest rates rise?" at flow.db.com