16 August 2023

With energy transition and net zero pathway objectives now embedded into many corporate strategy and operational plans, the role of the bank is evolving to one of partnership and support as companies seek to decarbonise. Deutsche Bank’s Lavinia Bauerochse shares her perspective on the journey

MINUTES min read

The global energy sector is racing to shift from fossil-based systems of energy production and consumption — including oil, natural gas and coal — to renewable energy sources such as wind and solar, as well as lithium-ion batteries. However, as more investors and companies factor long-term physical climate and transition risks into their strategic planning and statutory reporting, a raft of challenges are emerging in the face of accelerated global energy demand and geopolitical volatility.

With supply chain disruptions (particularly those involving essential minerals and metals needed for clean energy production), financial investment requirements and changing global regulations to contend with, implementing the energy transition has been described as “perhaps the greatest challenge humankind has ever faced” by Dr. Fatih Birol, Executive Director at the International Energy Agency (IEA). It was this transition to net-zero that was the main focus of my 2022 lead flow article, How to manage transition to net-zero. A year on, this article provides further insights into how net zero commitments and regulatory momentum shape the operations of companies and the financial community that supports them.

Narrow but achievable?

In 2021, to support the fundamental changes that are needed to avoid the most severe impacts of climate change, the IEA set out the world’s first comprehensive study of how to transition to a net zero energy system by 2050.1 The path to net zero requires accelerating the shift to non-emitting sources of energy (such as wind and solar), increasing energy efficiency and electrifying transport, industry and buildings, while expanding the use of clean hydrogen and other low-emission fuels – all at significant scale and speed. Two years later, the IEA sticks by this study as “a narrow but achievable pathway to net zero emissions – a trajectory consistent with limiting global temperature rise to 1.5˚C”, in accordance with the 2015 Paris Agreement.2

But how can this systemic change and complex pathway be achieved by 2050? According to a 2023 report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), finance, technology and international cooperation are critical enablers for this accelerated climate action.3 The ground-breaking paper indicates (with a rating of ‘high confidence’) that if climate goals are to be achieved, both adaptation and mitigation financing will need to increase substantially – because while there is adequate global cash to bridge the global investment gaps, there are hurdles to diverting wealth for climate action.

“Regulatory frameworks and stimulus packages are shaping the industry response to the climate transition”

Regulation driving banking response

Increasingly, regulatory frameworks and stimulus packages are shaping the industry response to the climate transition. In 2022, the US unveiled the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) – the first major climate legislation by the country’s federal government since the Clean Air Act was amended in 1990. It allocates around US$370bn (or 1.4% of 2022 GDP) to carbon-free energy, transportation, clean tech and financing for new industrial plants over the next 10 years.4 In Asia-Pacific, India’s National Action Plan on Climate Change (NAPCC) outlines eight “national missions” on climate change, renewable energy and environmental issues, and allocates two-thirds of its most recent stimulus package to a “green recovery”.

But to date, Europe has played the most significant role in driving the environmental, social and governance (ESG) agenda, pioneering wide-reaching regulatory initiatives. In 2020, the European Central Bank (ECB) published a guide on climate-related and environmental (C&E) risks, explaining how banks are expected to manage and transparently disclose such risks.

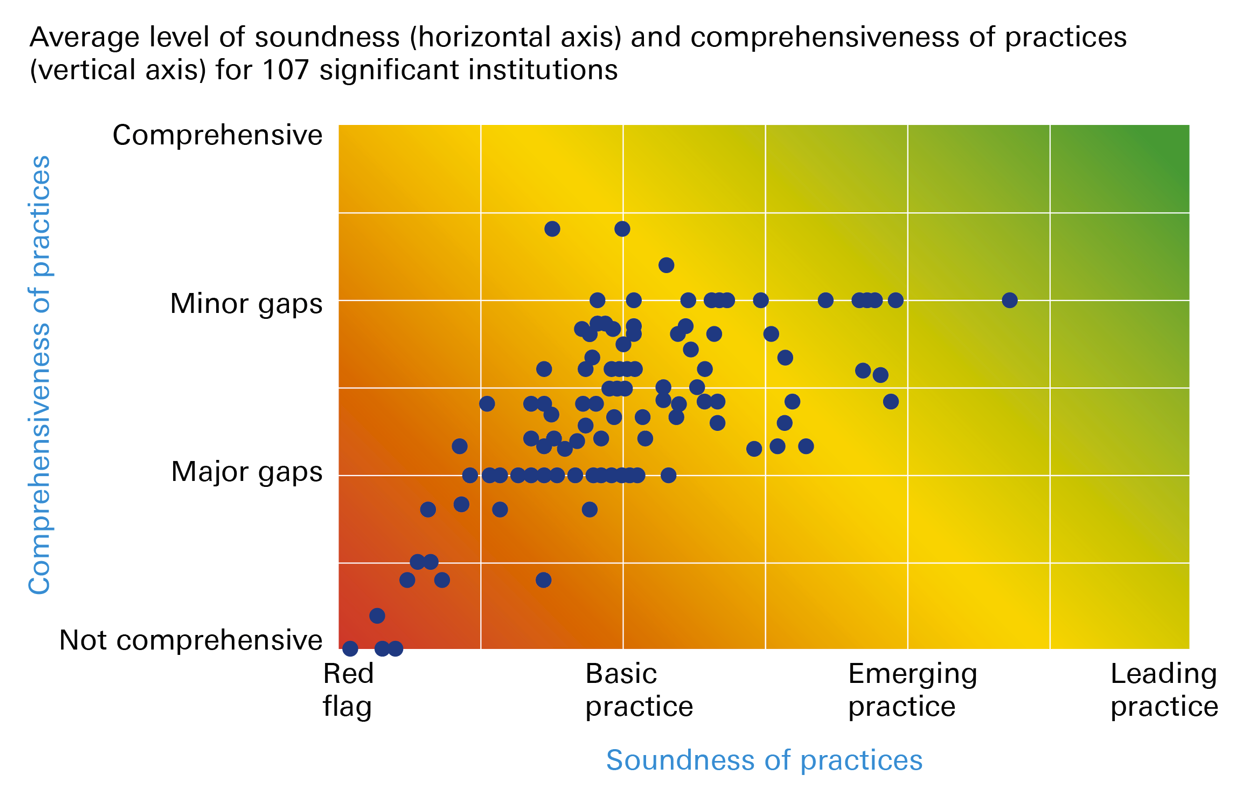

More recently, in November 2022, the European institution released the results of a thematic assessment of the extent to which 186 banks – with total combined assets of €25trn – were aligning with these expectations.5 The ECB’s findings shine a light on the current state of the financial services industry. While there is broad acknowledgement within the banking sector of the materiality of physical and transition C&E risks, the majority of institutions in scope have to further build soundness and comprehensiveness of their practices in managing climate risks. In fact, blind spots in the identification of C&E risks in key sectors, geographies and risk drivers were identified in 96% of institutions and, of these, 60% were considered to show major gaps (as demonstrated in Figure 1).

Figure 1: ECB stress test – Soundness and comprehensiveness of institutions’ practices to manage C&E risks

Source: European Central Bank

The ECB’s climate stress test underlines how the current state of the financial services industry is still far away from what the regulator expects. There needs to be far-reaching and enduring efforts to develop consequential, granular, and forward-looking approaches to manage C&E risks. It also demonstrates that the regulators will continue to push financial institutions towards energy transition and that those not up to speed will need to do their homework to keep up – emphasising the message that energy transition is not just a voluntary contribution but something enforceable by regulation.

Going forward, banks will be expected to engage more intensively on environmental and climate- related risks with their corporate clients. This could involve the banks requesting sustainability data from corporates, for example, through specific questionnaires to identify risks that are insufficiently captured by traditional credit risk analysis. In future, there also could be capital implications that would see risk premiums and pricing affected by environmental and climate-related risk factors. There is likely to also be heightened engagement on decarbonisation where bank appetite for corporates unaligned with decarbonisation targets is limited, depending on prevailing regulatory guidelines.

Exposure to financed emissions

For Deutsche Bank, a deep dive into its corporate loan portfolio found that the total exposure of financed emissions totalled 30.8 million tonnes of CO2 equivalent (Scope 1 and 2). It also highlighted that the three most carbon-intensive sectors – oil and gas; utilities; steel, metals and mining – account for 68% of the total exposure compared to their 16% share of corporate lending. As the sectoral exposures are managed under the industry risk framework which includes assessment of an industry’s vulnerability to climate and wider ESG risks, the automotive sector was also highlighted due to its high Scope 3 emissions in downstream activities.6

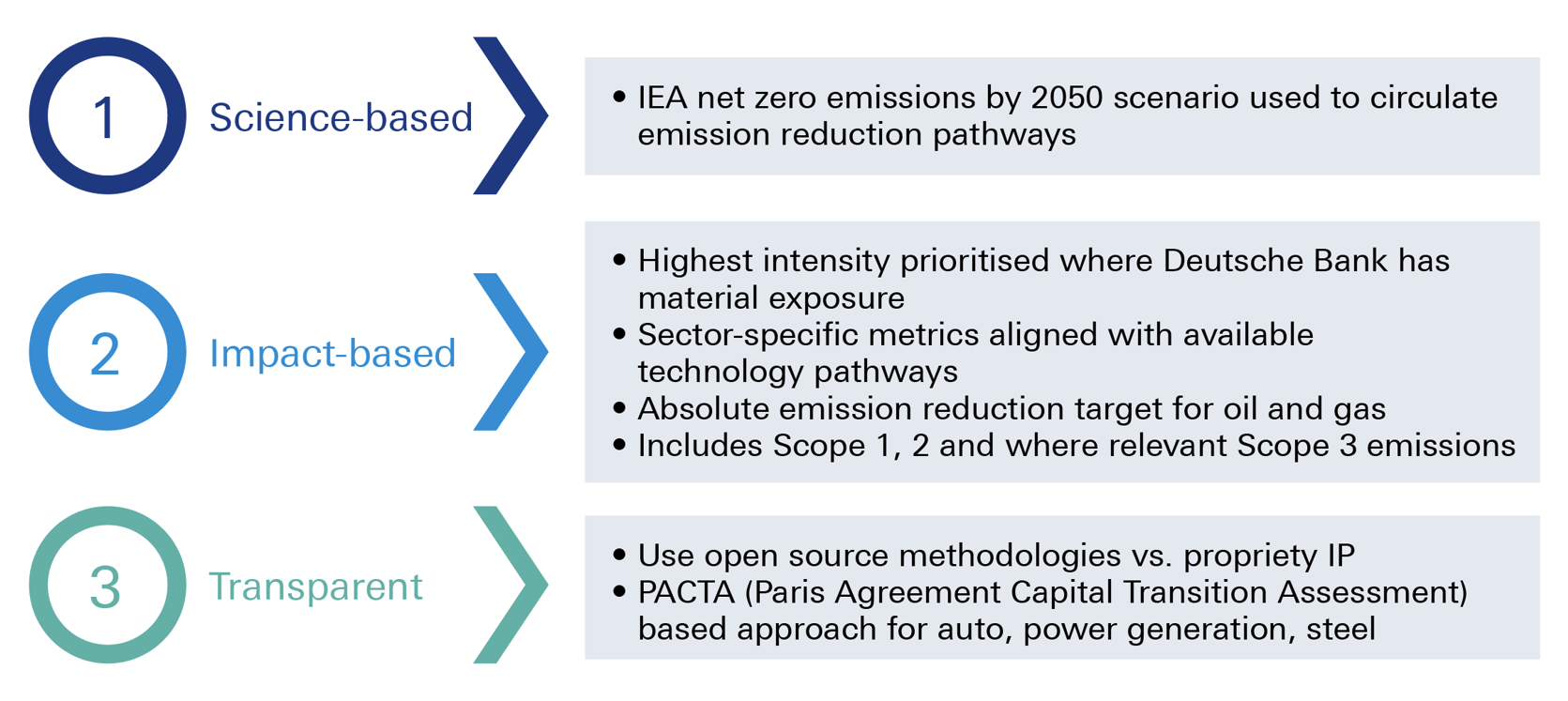

With the most carbon-intensive areas identified, the next step is developing a methodological, credible and robust approach to net zero alignment, which supports a progressive and orderly phase-out of fossil fuel usage while incentivising the financing of lower carbon-intensity technologies and clients with credible transition plans. Deutsche Bank’s target setting approach is aligned with key principles outlined by United Nations Environmental Programme Finance Initiative (UNEP FI) and Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ), and is shaped by the following science-based, impact-based and transparent principles.

Figure 2: Deutsche Bank’s target setting approach

Source: Deutsche Bank

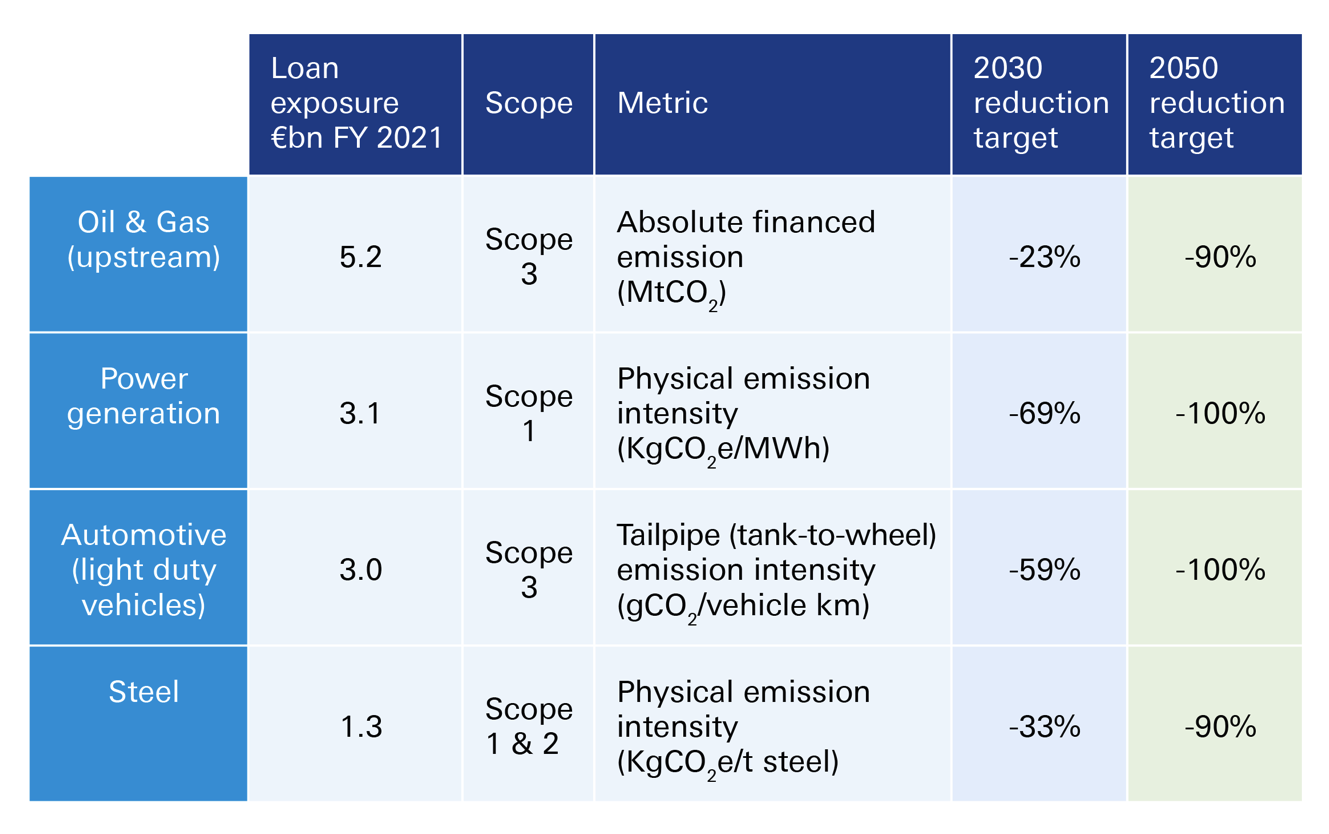

Galvanised by the ECB’s call to “walk the talk”, Deutsche Bank set the following respective 2030 and 2050 group-wide reduction targets for the bank’s four most carbon-intensive sectors, in line with the IEA’s net zero emission scenario which limits global warming to no more than 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels by 2100 (as shown in Figure 3):

- Oil and gas (upstream): 23% reduction in Scope 3 upstream financed emissions by 2030, and 90% reduction by 2050, in millions of tonnes of CO2.

- Power generation: 69% reduction in Scope 1 physical emission intensity by 2030 and 100% reduction by 2050, in kilogrammes of CO2 equivalent per megawatt hour.

- Automotive (light duty vehicles): 59% reduction in tailpipe emission intensity by 2030 and 100% reduction by 2050, in grammes of CO2 per vehicle kilometre.

- Steel: 33% reduction in Scope 1 and 2 physical emission intensity by 2030 and 90% reduction by 2050, in kilogrammes of CO2 equivalent per tonne.

Figure 3: Sector-specific metrics for Deutsche Bank’s net zero journey

Source: Deutsche Bank

To pursue these targets, Deutsche Bank is deploying three principal levers:

- Providing transition financing to clients to facilitate their transition;

- Rebalancing loan portfolio towards clients with greater focus on developing decarbonisation plans; and

- Reducing exposure to clients with limited capacity or willingness to decarbonise.

Deutsche Bank CEO Christian Sewing said in the bank’s Sustainability Deep Dive held in March 2023, “We have published our net zero pathways for the most carbon-intensive sectors. From 2026 onwards, at least 90% of the high-emitting clients in these sectors that engage in new corporate lending transactions with us shall have a net-zero commitment in place.” He added, “We at Deutsche Bank are convinced that parting with a client should only be a last resort, but we would not be shy of taking this step if we cannot see the willingness of our client to start a credible transition. In principle: we can only support our clients and have the necessary impact if they are still with us.”

Decarbonising supply chains

During the Covid-19 pandemic, we saw how companies – and indeed financial institutions – enhanced their digital technologies and workflows to digitise processes that had, in the past, been manual. The pandemic highlighted concentration risks and alarming fracture points. As corporates sought to inject more resilience into their supply chains, some started to identify opportunities for decarbonisation, and reductions in not only Scope 1 and 2 emissions but also Scope 3 emissions (the emissions with which the business is indirectly responsible for, as a result of its supply chains).

We’re now seeing that decarbonisation has become the second push to move process digitisation forward. Three years ago, in the start of the pandemic, KPMG published a report, Digitisation and decarbonisation in the new reality (2020), which made the somewhat prophetic point: “We believe that the acceleration of digitisation and integration of digital trust practices in a post Covid-19 world will provide the tools and solutions necessary for decarbonisation to gain a robust foothold in corporate operations.”7

In a climate where a pandemic has been superseded by geopolitical shocks such as the Russia/Ukraine conflict and tensions between the US and China, the resilience of supply chains has shifted into focus more than ever before. This has presented the perfect opportunity to think about how to integrate ESG criteria into the decision matrix, using digital tools to assess the carbon impact of operations and shipping, as well as traceability and transparency of products and inputs.

As the global economy begins its clean energy transition, rare earth metals will become increasingly important. They are essential raw inputs used to manufacture wind turbines, photovoltaic solar panels, and batteries. Around 95% of electric vehicles still use rare earth permanent magnet motors. In 2020, the World Bank found that the production of critical minerals, including rare earths, could increase by nearly 500% by 2050 if demand for clean energy technology continues to accelerate.8 However, primary supply and production is often geographically concentrated.

“Green and digital technologies currently depend on a number of scarce materials. We import lithium for electric cars, platinum to produce clean hydrogen, silicon metal for solar panels. 98% of the rare earth elements we need come from a single supplier: China. This is not sustainable. So, we must diversify our supply chains,” said Ursula von de Leyen, European Commission President in 2021.9

The race has begun for countries to establish a secure, independent supply of renewable energy commodities in a sustainable manner. This is hardly a straightforward task, given that processing can consume huge amounts of acid and water, with radioactive by-products of rare earths processing being another key concern.

Partnership functions

In summary, financial partnership in the clean energy transition means not only allocating balance sheet to renewable energy projects that will add precious kilowatts to national grids but providing financial support to finance the transition and decarbonise the real economy and supply chain.

Sources

1 See iea.org

2 See iea.org

3 See ipcc.ch

4 See DB research report: 17 January 2023. US Inflation Reduction Act: what's in it and how the EU might respond

5 See bankingsupervision.europa.eu

6 See db.com

7 See assets.kpmg.com

8 See pubdocs.worldbank.org

9 See eit.europa.eu