04 September 2020

As the European Union (EU) absorbs its €2.364trn pandemic support and rebuilds, how can the market forces/state intervention balance be managed to avert market failure? flow’s Clarissa Dann and Graham Buck reflect on insights from Deutsche Bank Research’s new paper on EU industrial policy

Europe discovered a sense of unity over the summer of 2020, as around €2.364trn of fiscal response to Covid-19 was injected into its member economies; a significant component of the overall US$10trn global bail-out total.1

While the deepest post-war recession for the world economy should eventually prove a temporary shock, the pandemic crisis highlights the delicate balance between state intervention (fiscal support being a prime example) and a playing field based on competition and free markets (protected by competition and antitrust rules). No economy can afford market failure as it returns to growth, but are the rules of engagement and notions of level playing fields being ripped up?

"Hot political debates about normalising the market mechanism and reinstating state aid rules can be expected over the next years"

“Hot political debates about normalising the market mechanism and reinstating state rules can be expected,” predicts Kevin Körner, Senior Economist in Deutsche Bank’s European Policy Research team in the briefing paper Industrial policy in times of Covid-19 and its aftermath, published 31 August 2020.

This article takes a closer look at the points his study and other complementary sources raise about the European Union (EU) bloc’s economic recovery perspectives and how industrial policy, along with the changing wider global economic, political and technological landscape could shape this. Framing all of this, as Körner puts it, is “the old debate about interventionism and protectionism”, along with implementation of digital transformation and climate change mitigation strategies.

Recovery race

Deutsche Bank Research forecasts a -4.1% year-on-year contraction for the world economy in 2020 but “the pain will be spread unevenly”, with a deeper fall of -8.6% projected for the euro area. In 2021 the world economy is expected to rebound by 4.9%, but will stabilise below pre-crisis trends due to demographics, fiscal fallout from the crisis, and ongoing US-China trade and technology tensions.

But Europe’s expected recovery is offset by its “subdued” long-term economic perspectives compared with China, other emerging markets (EMs) and the US. This partly reflects differences in demographic trends and productivity, and an “increasing technological gap”. The speed of recovery could, says the Deutsche Bank briefing paper, determine the relative economic performance of global competitors for many years. It has already deepened tensions between the two major economic powers, the incumbent US and rising superpower China.

Late 20th century EU economic policy reflected the belief that global market forces delivered the best economic results and most efficient allocation of resources, with a relatively limited role for government. Economic integration through the single market and launching the euro made interventionist industrial policy at national level a sensitive issue, while EU competition law limited the scope for national state aid.

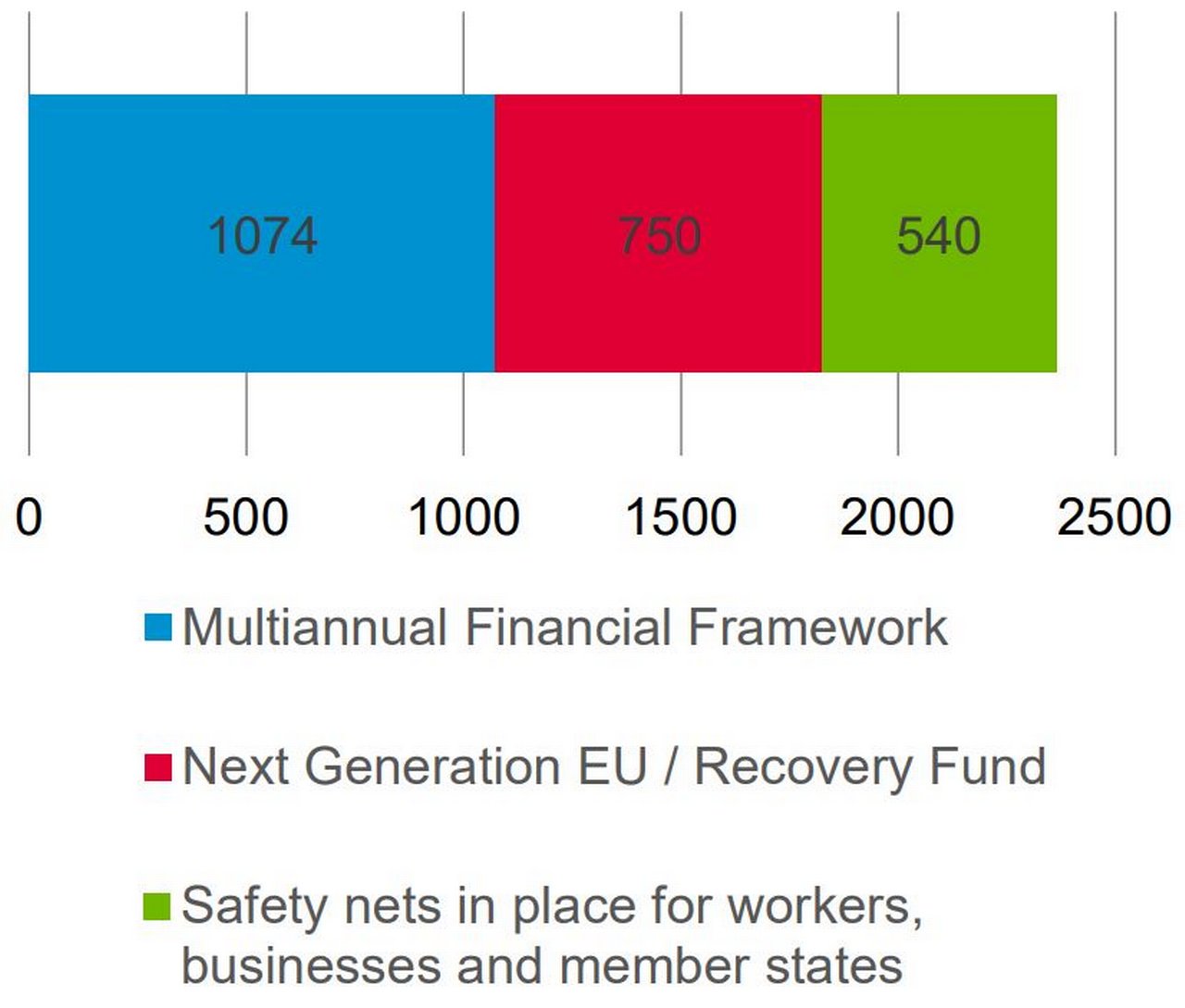

Figure 1: Recovery plan for Europe, €bn

Source: European Commission, European Council

In July 2020, European leaders agreed a €750bn crisis recovery package, on top of a €1.074trn EU budget over seven years and its earlier €540bn crisis package. The EU’s total fiscal response to the crisis therefore amounts to €2.364trn, aimed at mitigating the immediate impact on its economy and social fabric.

While the measures are designed to lessen the damage to the economic base and speed up recovery, there are longer-term implications; something Deutsche Bank’s Jim Reid has pointed out. In Early Morning Reid: Macro Strategy (14 April 2020) he says that “state sponsored capitalism” has meant that “each subsequent default cycle (or mini market cycle) has been less severe than the free market parallel universe version would have been and has left increasingly more debt in the system as a result and meant that the intervention necessary to protect the system has got greater and greater.” He adds, “In my opinion, it also helps lock in lower productivity as you keep more low/no growth entities alive.”2

Towards a level playing field?

Much more also needs to be done to ensure that everyone, from companies to countries, plays by the agreed rules

The OECD reminds us in its policy brief Levelling the playing field, “Where fairness is questioned, the sustainability of open global trade and investment is at risk. Whether it is rules that ensure that private and state-owned firms compete on the same terms, or that countries are not able to subsidise their own firms or farms at the expense of others, governments have an important role to play in negotiating disciplines that level the playing field in global trade and investment. Much more also needs to be done to ensure that everyone, from companies to countries, plays by the agreed rules.”4

However, perception has grown among EU (and other trading bloc) leaders that market forces alone might not be enough to keep Europe afloat.

In the 2000s, calls for stronger regulatory efforts as well as direct government intervention grew louder. Covid-19 “finally shifted the tide” towards a more prominent role for the state in the economy. Industrial policy, previously sidelined in Western market economies is, says the briefing paper, again fashionable due to several factors:

- Faith in the corrective mechanism of markets was shaken by the 2008 financial crisis and its aftermath. Several South Europe economies experienced a long and painful recoveries and have since suffered weak growth trajectories.

- The impact of technological change and digital transformation on EU industries and broader economies has become more visible. Europe seems behind in key technological fields, risking its long-term competitiveness and prosperity.

- Mitigating climate change challenges Europe’s industrial economies, while the transition towards green economies requires a concerted and socio-economically challenging transformation.

- Shifting global economic and geopolitical balances reveal Europe’s economic vulnerabilities. China’s rise as a “strategic rival” in key industries and technologies and the success of its state capitalist economic model challenge the EU’s own perception as an innovative and efficient high-tech economy.

- EU leaders had to respond to Covid-19’s economic impact and the need to address post-pandemic growth and development prospects.

- Dependency on global value chains, importing essential goods such as healthcare equipment and recent trade wars caused EU leaders to reassess the preferred degree of global economic integration and strengthened the belief that strategic independence and technological sovereignty should become political priorities.

Calls for a coordinated and holistic European policy approach to industry have grown. On 10 March 2020, the EC released A new industrial strategy for Europe4 followed on 17 June by the white paper, Levelling the playing field as regards foreign subsidies.5

“Openness to trade and investment is part of the economy’s resilience, but it must go hand in hand with fairness and predictable rules. The current global economic environment is the most difficult in recent memory,” says the white paper.

The pandemic has seen the EC temporarily suspend key aspects of competition law on state aid and antitrust rules, which normally protect the single market against distortions and anti-competitive conduct. But this is not designed to be any kind of new normal. Looser state aid rules enabled member states scope to support their economies. The framework is set to expire at the year-end and member states must notify the EC about state aids and justify them.

Despite a coordinated approach, the size and scope of state aid among member states varies. About half the €2trn approved by the EC in May 2020 came from Germany. Concerns have developed that differences in fiscal firepower among EU members may lead long-term to unequal conditions and distortions of competition in the single market. One recent controversy arose from the German government’s €9bn rescue package for Lufthansa (with the state taking a 20% stake), approved by the EC.6 But it is not the only government to channel state support into its aviation industry. The George Mason University notes that from 2007 to 2017, 34% of all aid from the US export credit agency, the US-Exim Bank “went to just one exporter: Boeing”.7

The changing global economic and technological environment and increasing involvement of non-EU players in the EU’s single market have highlighted regulation that needs updating.

“Increasingly, the single market showed itself exposed to unfair competition, the risk of forced technology transfer and increased import dependencies in critical areas such as healthcare or infrastructure,” says Körner. He adds, “Issues of lacking reciprocity when it comes to market access and intellectual property rights, in particular with China, remain insufficiently resolved. Unfair trade practices repeatedly led to legal proceedings in the WTO, even though the role of the institution as a trade arbiter was paralysed in the ongoing trade war between the US and China.”

The EU has already started addressing some issues. A foreign direct investment screening framework monitors and advises members on foreign investments in strategically important sectors. The industrial strategy foresees an Intellectual Property Action Plan to uphold technological sovereignty, promote a global level playing field, better fight intellectual property theft and adapt the legal framework to the green and digital transitions.

European Commission goals

In 2019, EU leaders asked the EC to develop a blueprint for a new European industrial policy. Published on 10 March 2020, A new industrial strategy for Europe8 proposes merging two goals:

- Reinforcing Europe’s industrial sovereignty and global competitiveness; and

- Transitioning to a green and digital economy.

“The twin ecological and digital transitions will affect every part of our economy, society and industry. They will require new technologies, with investment and innovation to match. They will create new products, services, markets and business models. They will shape new types of jobs that do not yet exist which need skills that we do not yet have. And they will entail a shift from linear production to a circular economy,” says the EU strategy report before the full impact of Covid-19 was apparent.

The objectives outlined in the document are:

- Green transition: Creating a green economy and supporting the industry in its leading role in the European Green Deal.

- Digital transition: A globally leading role in the digital economy, supported by the Commission's digital strategies. Bolstering the EU's critical digital infrastructure and the rollout of 5G are core elements.

- Global competitiveness and sovereignty: Strengthening competitiveness by reinforcing the single market, upholding open markets and fostering a global level playing field. A revised competition framework is due by October 2020.

In addition, the industrial policy strategy is supported by a strategy for SMEs as key players for innovation and for the twin objectives of green and digital transition. The EU report, Unleashing the full potential of European SMEs, (March 2020) points out that the bloc’s 25 million SMEs generate half of the EU’s GDP, provide two out of three of its jobs and that 50% of them undertake some form of innovation activity. It also notes that SMEs need better access to finance with only 10% of their external finance coming from the capital markets. “The SME strategy will reduce barriers within the Single Market and open up access to finance to cover the investment needed for the ecological and digital transition,” says the report.

A joint European approach to industrial policy

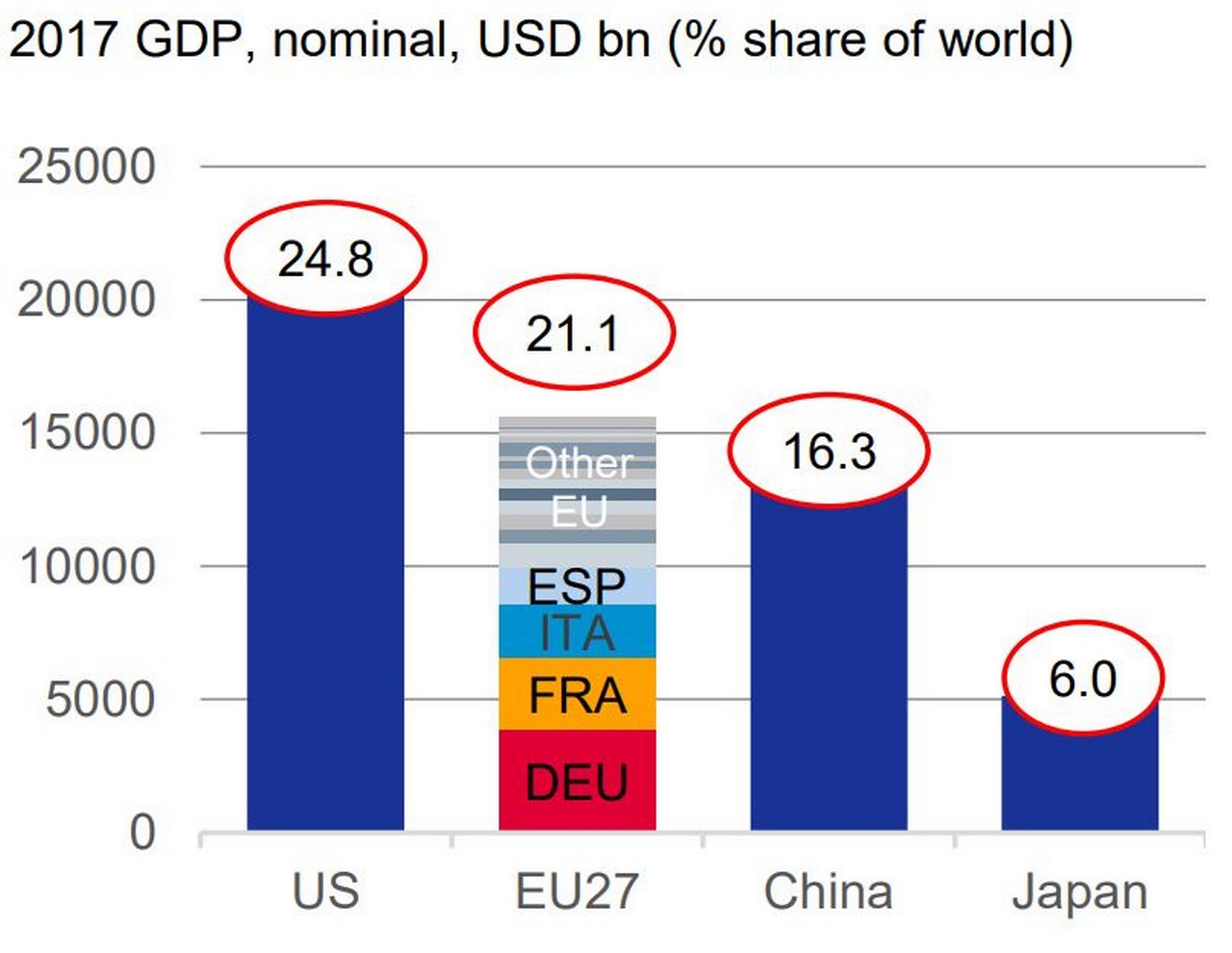

Figure 2: Fragmented European Economy

Sources: IMF, Deutsche Bank Research

The scope for national industrial policies is limited by EU member’s smaller economies and constraints on industrial policy under EU law, notes the Deutsche Bank Research briefing paper. Collectively, the EU27 economically plays in the same league as the US and China, but individually even Germany and France are dwarfed by the two superpowers (see Figure 2). A Franco-German “manifesto” of 2019 acknowledged that Europe “must pool its strengths” and develop a “genuine European industrial policy strategy” to remain a “manufacturing powerhouse in 2030”.

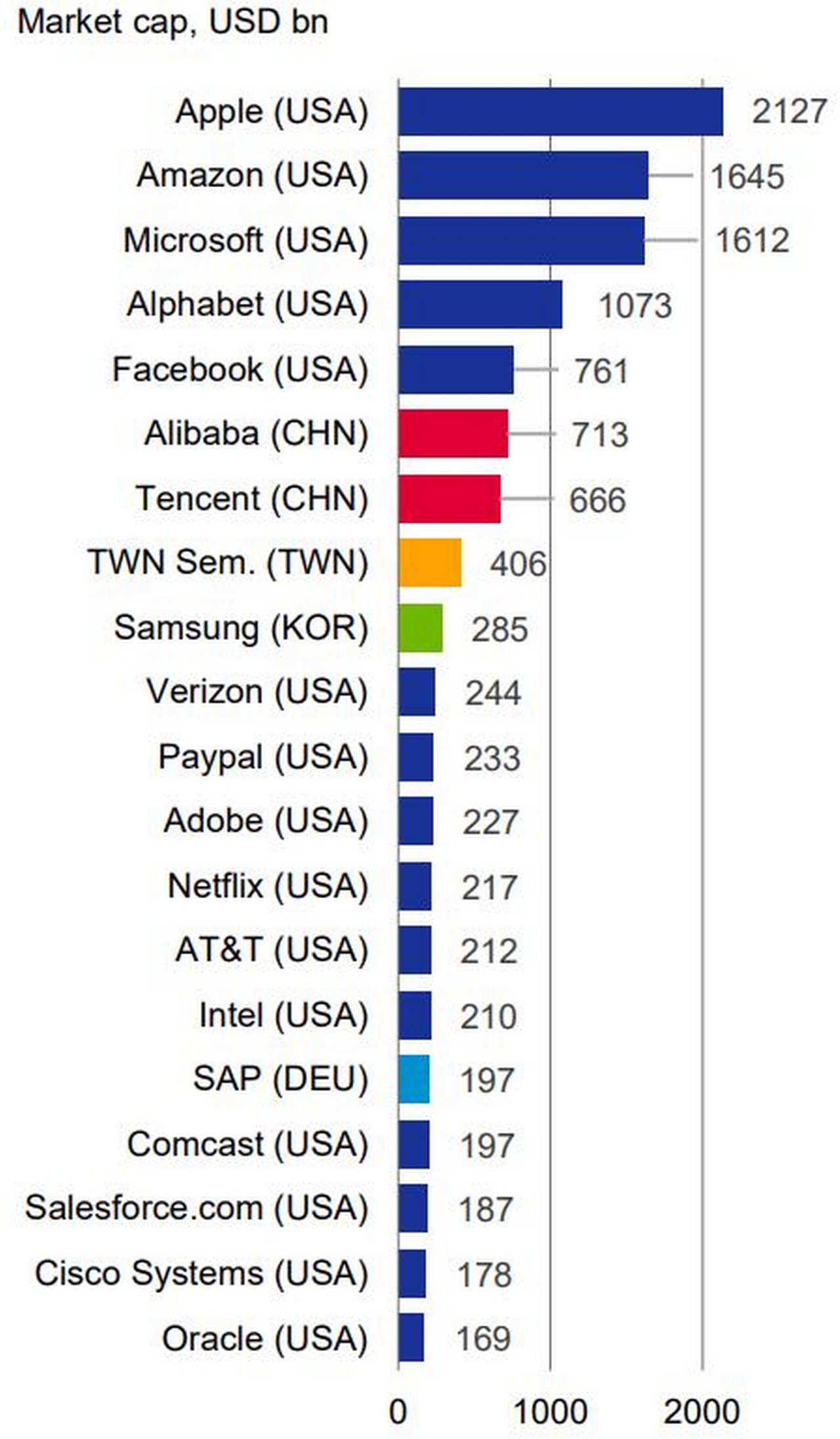

Figure 3: Companies from the US dominate the technology sector

Note: Market capitalisation as per August 24, 2020

Source: Bloomberg Finance LP

In the digital economy, the EU is most at risk of being left behind. The top 20 tech companies include 15 from the US, two from China and one from Europe (see Figure 3). Global stock markets tell a similar story: in 2020 the largest 500 companies based on market capitalisation shows a smaller share of European companies than 20 years ago. The US and China also substantially outperform Europe when it comes to “newcomers” listed since 2000.

European industry (including construction) represents 20% of the bloc’s total value added and has followed a slowly declining trajectory since 1990. Over the period the service sector’s share in total GDP settled at around 65%. Manufacturing declined to around 15% of the EU's economy, against just 11% in the US, but 20+% in Japan and almost 30% in China.

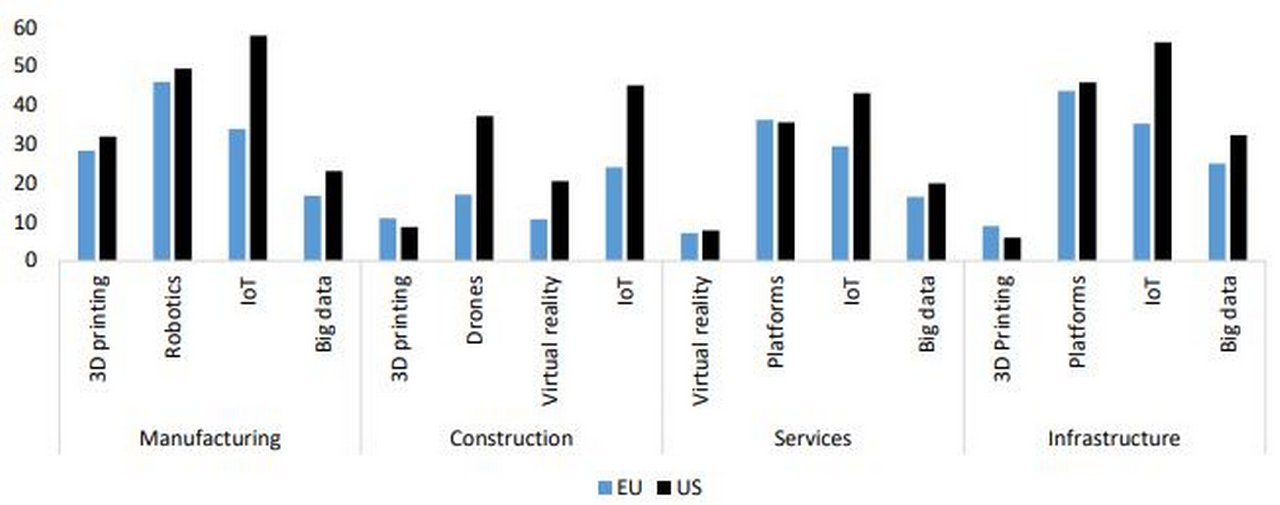

The rise of the data economy has further boosted the importance of services and intangible goods. At the same time, physical and virtual economic processes are growing rapidly together, reflected in increased automation and Internet of Things (IoT) applications in manufacturing and services. The annual European Investment Bank survey on Investment and Investment Finance (EBIS) was published on 20 April, entitled Who is prepared for the new digital age?9 The responses were from 13,500 firms include include those from all EU member states, as well as a sample of US firms, which serves as a benchmark. Its findings highlight the slow adoption of digital technologies in the EU when compared with the US (see Figure 4).

However, the EIB (in line with many other insights on the pandemic) notes the pandemic “could become a tipping point for digitalisation − a dawn of a new era − by accelerating the maturity of digital technology: What was once a ‘nice to have’ could now become a ‘crucial to have.”

In other words, this survey could look a bit different in a year’s time.

Figure 4: Adoption of digital technologies in the EU and the US

Note: Share of firms that have implemented (or organised their entire business around) each technology. Firms are weighted using value added. IoT: Internet of Things.

Source: EIBIS 2019.

Green front runner

The European Green Deal is a key element of the EU’s industrial strategy. This includes “comprehensive measures to modernise and decarbonise energy-intensive industries, support sustainable and smart mobility industries, to promote energy efficiency, strengthen current carbon leakage tools and secure a sufficient and constant supply of low-carbon energy at competitive prices”.

The EU aims at large-scale investment in climate and environmental action over the next decade, with a key role for the EIB. Headed “striving to be the first climate-neutral continent”, the reports states that 30% of the EU’s budget over the next seven years as well as the recovery fund, i.e. a total of above €500bn, will be dedicated to climate action and clean energy.

While green transition is a key industrial policy objective of the EC, the Deutsche Bank Research briefing paper makes the point that there needs to be further investigation of how it relates to other industrial policy goals, in particular regarding the EU international competitive position and the ambition to become less dependent on imports and to re-shore production in key sectors.

This requires substantial investments and close cooperation between the industry, governments and academia. “But if other industrial blocs, in particular the US and China, continuously fail to follow suit on the EU’s climate agenda over the next years and decades, the EU’s industry will increasingly feel the competitive pressure,” it notes.

Digital champions

A key issue of European industrial policy centres on creating digital champions, with EU members for companies big enough to stand up against global competitors. But how big is too big in the eyes of the competition watchdogs?

The debate resurfaced in 2019 when the EC vetoed the planned Franco-German rail merger between Alstom and Siemens.10 The deal would have brought together the two largest suppliers of various types of railway and metro signalling systems, as well as of rolling stock in Europe. Commissioner Margrethe Vestager, in charge of competition policy, said at the time, “Millions of passengers across Europe rely every day on modern and safe trains. Siemens and Alstom are both champions in the rail industry. Without sufficient remedies, this merger would have resulted in higher prices for the signalling systems that keep passengers safe and for the next generations of very high-speed trains.”

From the perspective of the EU’s single market, this is a “complex issue” says Körner. Creating national or EU champions could severely distort EU markets and give such companies advantages that might suppress competition and innovation. On the other hand, network externalities and scale in the digital economy particularly favours large companies. Alphabet and Facebook have shown how large and dominating digital ecosystems are speedily created and dominate Europe’s digital economy. Meanwhile, global competitors such as China demonstrate how combining protected home markets and state support can quickly lead to globally competitive players with increasing market shares abroad.

China’s ambition to achieve global innovation and technology leadership by the mid- 21st century is “a wake-up call for EU governments” from both an economic and geopolitical perspective. While the Chinese model is unavailable (and unwanted) under EU regulation, governments and authorities need to address the issue, says Körner in the Deutsche Bank briefing paper.

Post-Covid industrial policy

While governments have accepted large-scale guarantees for private sector risks, launching vast support and recovery programmes that escalate debt levels and reduce fiscal leeway for many years. Once the crisis abates, fierce political debates on normalising market mechanism and reinstating state aid rules can be expected. Post-Covid insolvencies of unprofitable companies that survived the crisis through state support might cause further economic disruptions. Even after the crisis, calls for continued exemptions to European state aid and competition rules are likely, risking lasting distortions and hurting the integrity of the single market.

As the bloc struggles to overcome the crisis and normalise economic conditions, the EU must face long-term challenges to its competitive edge and prosperity posed by the rapid global economic and technological transformation. Having accepted a global front-runner role in green transition, it needs to be closely streamlined with its other industrial policy objectives. The EC’s strategy to address these issues in an integrated way is a crucial step in formulating a joint European response to “formidable economic and geopolitical challenges” over the decades ahead.

“Much will also depend on the ability and willingness of EU members and governments to stand together,” concludes Körner.

Summary of Deutsche Bank Research reports referenced

Early Morning Reid: Macro Strategy on 14 April 2020 by Jim Reid

Industrial policy in times of COVID-19 and its aftermath (31 August 2020) by Kevin Körner

Sources

1 See Kicking the can: who pays for Covid-19? at flow.db.com

2 See Central banks: on-side or outside? at flow.db.com

3 See https://bit.ly/3hURnnd at oecd.org

4 See https://bit.ly/3bpGpn3 at europa.eu

5 See https://bit.ly/3hWpvim at europa.eu

6 See https://bit.ly/3jBdzmG at theguardian.com

7 See https://bit.ly/3jFsIn4 at mercatus.org

8 See https://bit.ly/3lKAVbj at europa.eu

9 See https://bit.ly/2EXQRGy at eib.org

10 See https://bit.ly/3blR8iB at europa.eu

Go to Corporate Bank EXPLORE MORE

Find out more about products and services

Go to Corporate Bank Go to Corporate BankStay up-to-date with

Sign-up flow newsbites

Choose your preferred banking topics and we will send you updated emails based on your selection

Sign-up Sign-upYou might be interested in

MACRO AND MARKETS {icon-book}

A Hellenic recovery A Hellenic recovery

After a prolonged bout of austerity, Greece was on track for an economic comeback before Covid-19. flow’s Graham Buck asks whether the pandemic has derailed the recovery, or merely delayed it

MACRO AND MARKETS, TRADE FINANCE, CASH MANAGEMENT

End of the tunnel End of the tunnel

With light at the end of the Covid-19 tunnel nearer for some regions than others, flow’s Clarissa Dann examines the pandemic’s economic impact and responses as households and firms plan for the eventual recovery

Cash management, Trade finance and lending, Macro and markets

GCC: four trends corporate treasurers should be aware of GCC: four trends corporate treasurers should be aware of

Digital transformation and infrastructure investment are top priorities in the Middle East as the region diversifies away from oil and gas. How does this impact the corporate treasury teams of companies operating in the region? flow’s Desirée Buchholz reports and shares two client examples from the Asia-Middle East corridor