September 2020

Germany’s €750bn aid package to help its businesses through the pandemic includes a loan scheme run by state development bank KfW and the commercial banking sector. flow talks to KfW’s Ingrid Hengster, who provides insights into how the scheme was set up and the difference it has made to future viability

When Germany went into lockdown on 22 March 2020, the ensuing economic shock and disruption to its business community was in danger of holding Europe’s largest economy back for decades.

Chancellor Angela Merkel was not going to let that happen. A €750bn aid package was approved three days later to mitigate the direct effects of the Covid-19 outbreak, despite the emergency measure requiring a suspension of the German government’s debt ceiling so that it could take on a further €156bn in 2020. This prompt action to future-proof its economy, together with its overall management of the pandemic, has been regarded as offering a blueprint to other countries.

Deutsche Bank Group Chief Economist David Folkerts-Landau observed in his research report Focus Germany: Covid-19 – Crisis Resilience Made in Germany (10 June 2020): “Germany’s often ridiculed fiscal frugality during the good times prior to the pandemic gave it the firepower to respond and will make it possible to come close to achieving the stated goal that no one should lose their job and no business should have to close its doors.”1

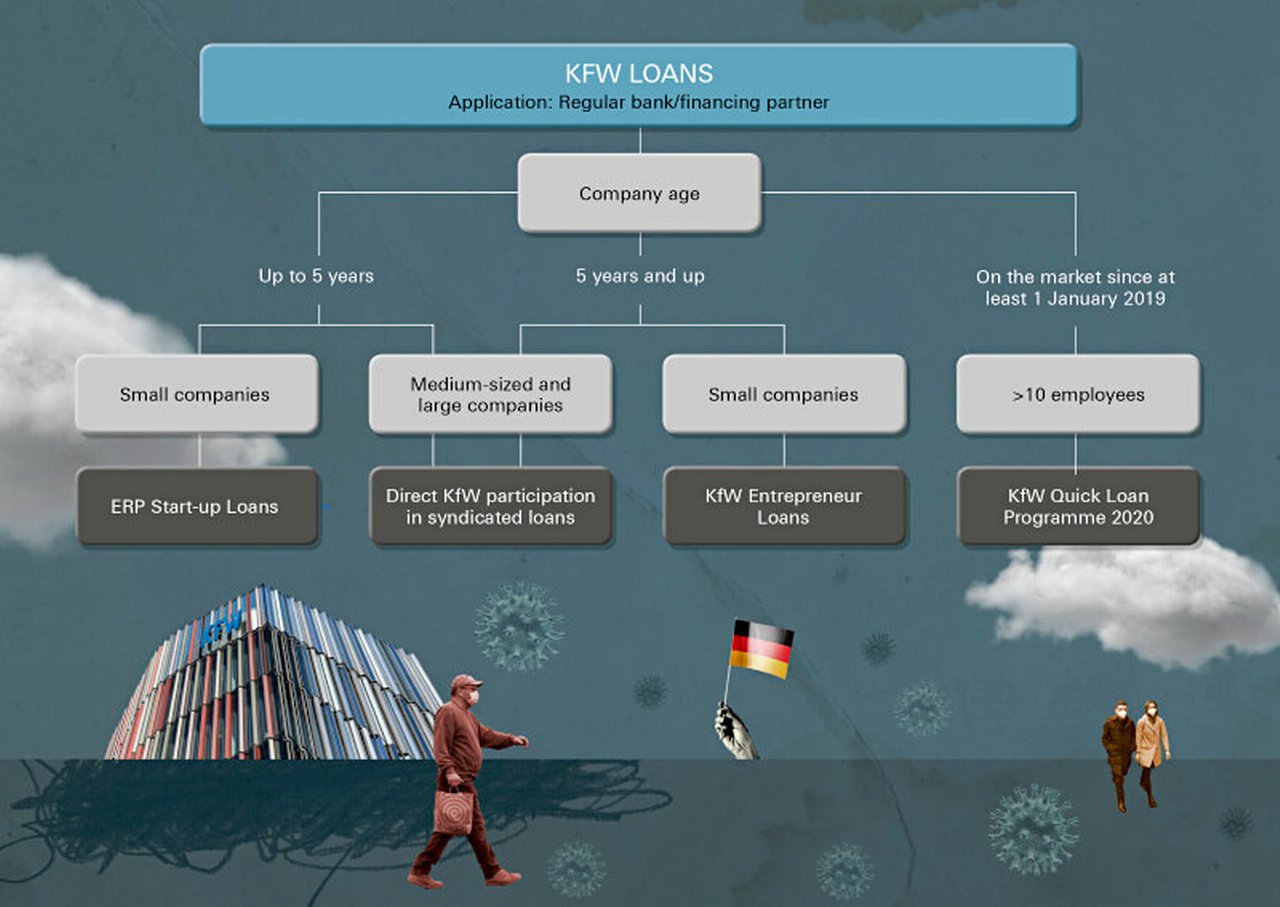

The measures cover compensation for employees, the self-employed and those on social security, and tax assistance measures. Included in the support was a range of loans and guarantees from Germany’s state development bank, KfW, delivered via its established commercial bank partners (it does not take deposits from citizens) – see Figure 1 on page 31. Banks from all three pillars of the German banking system – savings banks, cooperative banks and private banks – were eager to be part of their country’s economic rescue plan.

As one of those partners, Deutsche Bank received more than 5,300 Covid-19-related enquiries, including more than 2,000 specific credit enquiries, at the start of the aid programme.2

Based on an interview with Ingrid Hengster, one of KfW Group’s Executive Directors overseeing the lending programme, this article charts the project’s journey from initial planning to roll-out and beneficiary impact.

“I sensed how big the crisis could become after seeing the images from China and watching the first infections emerge in Italy, and later Germany,” recalls Hengster. “As a result, we were already working with the government on a response in February, well before the shutdown was ordered in late March.” Once the call to action was issued, she adds, “We did not have the time to sit down and analyse the situation in great depth. Speed was of the essence. Jointly with our partners, we quickly rolled out a wide-reaching programme that delivered massive support to companies of all sizes – from smaller businesses to the DAX companies.”

Around the clock

From February 2020 onwards, all the institutions involved were working around the clock. “Looking back, it’s quite astounding to see how much was accomplished in a very short time,” says Hengster. She ascribes this to the focused teamwork between KfW and all its partners in the German government, the regulators, and the commercial banks, such as Deutsche Bank.

She continues: “I’m extremely appreciative and proud of our teams at KfW for their amazing work. I am also very grateful for the intense exchange with the credit institutions like Deutsche Bank and others, and I want to thank Deutsche Bank for their cooperation. While our collaboration was already very good in the past, this crisis has brought us even closer together.”

KfW handled the switch to remote working quickly thanks to robust business continuity management planning, increasing its remote workplace capacity from 800 employees pre-crisis to more than 2,000 within a couple of days. Currently, up to 90% of all staff can work from home at any time.

Hengster pays tribute to colleagues who juggled extra hours to process what were called “the Corona loans”. Many have young children who suddenly had to be educated at home, although her own son is a teenager and did not need such an intense level of parental supervision. While she understands that a combination of remote and office working will be the new normal for all of us, she admits that she feels more at ease in the office. “I enjoy the direct exchanges with my colleagues, as I appreciate the personal impulses and interaction,” she explains – her role being one that could not entirely be performed remotely.

Figure1 : KfW's range of 'Corona loans'

Source: German Federal Ministry of Finance

Spirit of the Marshall Plan

KfW sees itself as being “useful wherever market weaknesses occur that can be mitigated effectively and efficiently with the specific instruments of a promotional bank”; “promotional” having the sense of promoting business and exports. These instruments are generally low-interest loans, guarantees, equity investments and grants.

It was founded in 1948 as Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau (Credit Institute for Reconstruction), and the early years of KfW Group were closely connected with the postwar economic development of the Federal Republic of Germany. Its formation followed US Secretary of State George C Marshall’s announcement of a financial aid programme for Europe (the European Recovery Program,3 also known as the Marshall Plan) after the devastation of six years of war.

Germany needed food, commodities and materials worth around US$1.4bn (€9bn/ US$10.3bn today), so purchase price payments for these imports then had to be used as so-called ‘counterpart funds’ for investments made through KfW. By the end of 1953, the bank had received several instalments totalling around €1.89bn, which it could then begin lending.

The partnership between KfW and the private banking system dates from this period, when these huge amounts of money were being invested to rebuild the country. “The system was created to use the individual strengths of the commercial banks and the public development banks,” explains Hengster. “It’s known as the ‘local bank principle’ and it takes advantage of the close relationship banks maintain with their customers all over Germany. For KfW, it means that we do not grant loans directly, but rather our clients receive the loans through their local bank. In this manner, we can rely on their expertise in assessing creditworthiness and risk, as well as providing the balance sheet capacity.”

"The German government is doing exactly the right thing by providing short-time work allowances and liquidity assistance"

Applying for loans

Asked by German newspaper Der Spiegel on 25 March if Deutsche Bank was the “bottleneck” when turning around the Corona loans (small businesses in particular were struggling because they could not get funding quickly), Head of Corporate Bank Germany Stefan Bender emphasised that creditworthiness checks are essential, and processes have been simplified considerably from what was originally a two-stage set of checks. He added: “KfW relies on our assessment for loans of up to €3m. For amounts between €3m and €10m, the requirements for the loan application have been streamlined significantly. KfW will only check support loans that exceed €10m.”4

Dealing with the sheer volume of applications would not have been possible had the process not been largely automated. Another KfW Director, Markus Merzbach, confirms that “KfW has already invested a great deal in digitalising the application channels in recent years.” Companies can apply for loans under the Covid-19 aid programme through their usual bank or another commercial bank. Options are the KfW Entrepreneur Loan, the ERP Start-up Loan – Universal, syndicated financings and the 2020 KfW Instant Loan.

Hengster reflects: “For the German government, it made a lot of sense to build on these well-established and tested procedures, processes and infrastructure to distribute the emergency funds. Of course, we had to follow the guidance of the Temporary Framework of the European Commission. For example, a company was not eligible if it experienced financial difficulties before the end of 2019, and it had to be able to demonstrate that it was healthy at the time of applying. This allowed us to offer 80–90% backing, and even 100% with the Instant Loan programme, which is a new product that was developed within days.” The European Commission agreed that the loan scheme was in line with state aid rules and then approved it under the EU’s Temporary Framework for state aid measures to support the economy in the current Covid-19 outbreak.5

“It is particularly important that the ECB and the European Banking Authority are now giving banks more flexibility to support their customers,” said Deutsche Bank CEO Christian Sewing in an interview with German Sunday newspaper Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung published on 16 March. “In principle, policymakers still have more leeway than the central banks, especially in countries like Germany, with its budget surplus. Short-term assistance for affected companies is important.6

“The German government is doing exactly the right thing by providing short-time work allowances and liquidity assistance,” he continued. “The experience of 2008 can help to cushion external shocks in this area.”

€54bn

After the scheme had been in operation for three months, loan application volumes topped €54bn and KfW had received 83,000 applications (and rising) from all over Germany. SMEs, reports Hengster, account for 99% of all loan applications and the median loan amount is €120,000.

“These businesses have been very healthy over the years and deserve their title as the backbone of the German economy,” she explains. “Many of them are hidden champions and global market leaders in their fields. They have increased their equity significantly since the financial crisis of 2008 and the average equity ratio amounts to an excellent 31.2%. That makes them quite resilient to the crisis. Our research has shown that the SMEs’ reaction to the crisis has been creative and flexible: 57% have already adapted their product offerings, sales channels or business models, or intend to do so. And we are confident that others will follow.”

"German SMEs have been very healthy over the years and deserve their title as the backbone of the German economy"

Crisis and innovation

In a June 2020 report titled Innovation in a Crisis: Why it is More Critical Than Ever,7 McKinsey revealed that its survey and interviews with more than 200 organisations of various sizes show that “many companies are deprioritising innovation to concentrate on four things: shoring up their core business, pursuing known opportunity spaces, conserving cash and minimising risk, and waiting until ‘there is more clarity’”. Unsurprisingly, the only industries that showed an increase in innovation were the medical and pharmaceutical sectors.

Digitalisation and further automation were already seen as important trends before the pandemic, notes Hengster, and the crisis has, in her view, accelerated the progress out of necessity, “increasing the sense of urgency about the need for innovative and digital businesses in Europe that can drive new technologies forward.

“In a way, we were shown an alternative future – one that many of us had not thought possible,” she continues. “Many people dropped their resistance to remote work, companies retooled their production to manufacture medical equipment, and schools made materials available on digital platforms. Not everything was perfect, but due to coronavirus, many of the excuses for not undertaking new developments will no longer be valid.”

In other words, nimble organisations that have shown they can deal with transformational change need to sustain the momentum and take the opportunity to “jump-start innovation in the fields of sustainability, in particular climate change and digitalisation. These were already our priorities at KfW and we will pursue them energetically,” Hengster adds.

The future

Despite the promising initiatives to find a vaccine, in Hengster’s view, the virus is going to be with us for quite a while. Nevertheless, she says, “I am impressed by how forward-looking companies are dealing with this situation and challenges and how creative they are in reshaping their future.”

As our interview concludes, it is clear that both Hengster and KfW as a whole are determined to be part of that future. “People have a natural survival instinct and an ability to adapt to changing circumstances. I believe in the ambition, resilience and creativity of the human being,” she declares. “Challenges remain, but I am looking forward to pursuing our goals together with our counterparts in government, our partner banks – like Deutsche Bank – and our colleagues at KfW.”

Dr Ingrid Hengster is Executive Director of KfW Group

Details of KfW’s coronavirus loans for companies can be found at https://bit.ly/2PbljyP, kfw.de

Sources

1 See Covid-19: How Germany gained its firepower at flow.db.com

2 See https://bit.ly/3jS2ZsB at db.com

3 See https://bit.ly/34gwsHo at britannica.com

4 See endnote 2

5 See https://bit.ly/3gj0woD at ec.europa.eu

6 See https://bit.ly/3jWzFkH at db.com

7 See https://mck.co/2D96vhF at mckinsey.com

8 See https://bit.ly/2PiujBX at kfw.de

CASE STUDY: STRANDHOTEL SEEROSE

Hotelier Gerd Schulz bought a premium property on the island of Usedom, in Northern Germany, for his hotel on the edge of Loddin East Beach in 1991, and so it was that the Strandhotel Seerose was born. Three years ago, when Schulz took out business closure insurance, he did not tick the ‘epidemics’ box. “That a global pandemic like coronavirus could affect me and the entire industry was beyond my imagination at the time,” he admits.

The hotel had its best year ever in 2019 and there were signs that 2020 would even beat this record. Schulz, who holds a degree in engineering, reported full booking calendars and an above average occupancy rate.

Even revenues in the winter months of January and February were 120% higher than in the same period last year. And then coronavirus hit. The last day of work for 90% of his 73 employees was 18 March 2020. “We still had a full house then,” says Schulz. “Business was booming.” He continued to pay his staff as usual for the month, but from 1 April had to send them home with reduced pay under Germany’s short-time work scheme.

The hotel and hospitality industry has been particularly hard hit by the containment measures. More than 11,000 overnight accommodations in Germany and over 71,000 restaurants are currently struggling to survive. “Still, every case is unique; the individual business models of hotels and restaurants are very different,” says Marcus Thiel, Head of Promotional Funds at Deutsche Bank.8 “We see our role primarily as an adviser to our customers, with a focus on securing liquidity. It was a challenge for us to manage the overnight increase in demand for KfW loans and to make KfW promotional funds available at short notice to all our 900,000 corporate customers.”

A combination of the KfW loan and the launch of a prepaid voucher scheme that guests could redeem once the hotel reopened has helped Schulz and his family survive during a testing time.

You might be interested in

MACRO AND MARKETS

ESG investing: roots to return ESG investing: roots to return

Covid-19 has changed the way investors view ESG, focusing more on performance than altruistic merit. flow’s Janet Du Chenne analyses Deutsche Bank research on what investors look for and the trends that are shaping the tools for predicting return

Trade finance and lending {icon-book}

Pillars of frontier economies Pillars of frontier economies

Multilateral development banks (MDBs) have been working with commercial banks to support crisis-torn economies to get back on their feet for decades. They do this with guarantees and in-country expertise, supporting critical imports and vital GDP-bolstering exports. flow shares insights on these transformational partnerships from three leading trade facilitation providers

MACRO AND MARKETS, TECHNOLOGY

China focuses on post-Covid goals China focuses on post-Covid goals

Having warded off the pandemic’s full impact, the world’s second-largest economy can focus on achieving technological self-sufficiency and developing its central bank digital currency, reports flow’s Graham Buck