14 August 2024

Multilateral development banks (MDBs) have been working with commercial banks to support crisis-torn economies to get back on their feet for decades. They do this with guarantees and in-country expertise, supporting critical imports and vital GDP-bolstering exports. flow shares insights on these transformational partnerships from three leading trade facilitation providers

MINUTES min read

When Sri Lanka defaulted on its foreign debt – except for its MDB debt – on 12 April 2022, the country was facing the worst economic crisis since its independence in 1948. Amid widespread unrest, President Wickremesinghe was elected the following July and the new government has been working with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to restructure its debt since.1

Kenya managed to avert default when several crises converged: inflation, commodity price volatility and pressure on the exchange rate and FX reserves, not to mention the most severe drought in four decades. Banks pulled their lines in 2022, but now, as Keith Hansen, World Bank Country Director put it in March 2023, “fiscal consolidation plays a central role in supporting Kenya’s macroeconomic foundations for inclusive and sustained growth.”2

"Economic and political uncertainty creates an environment that Is often deemed too high risk"

For Sri Lanka and Kenya – and many other frontier economies around the world – economic and political uncertainty creates an environment that is often deemed too high risk for financial institutions, which can negatively affect their ability to access commercial bank money. By reducing the cost of risk weighted capital, MDBs can play a key role in connecting these markets with much-needed additional sources of finance. This is in addition to their vital non-financing activities such as training, policy and advocacy work carried out in support of their trade-development mandates.

Ukraine is another recent example of the critically important role that MDBs play in markets which are all but closed to normal commercial banking facilities. Since the outbreak of the Ukraine-Russia war, the EBRD (European Bank for Reconstruction and Development) and IFC (International Finance Corporation), together with the World Bank, have demonstrated additionality by providing extensive financial support through risk-sharing guarantees and direct financing. These facilities support the rebuilding and upgrading of industrial infrastructure and the agribusiness, food production, healthcare, construction and energy industries, thereby sustaining the Ukrainian economy and saving the population from the most dire effects of the war.

Beyond country risk

Financial institutions that have had a long history of working with frontier economies tend to see past the spectre of the risk of defaults, especially when it comes to financing the flow of important commodities and cash crops.

This is particularly true of the African continent, home to around 30% of the world’s reserves of critical minerals and metals such as platinum group metals (PGMs), cobalt and manganese, which are, explains Pangea-Risk CEO and Founder Robert Besseling, “essential for renewable energy technologies and the broader transition towards a net-zero global economy”.3

"We should be able to attract financing into countries that need it"

“Africa has been steeped in the narrative of sovereign defaults and near defaults,” he adds. Credit rating agencies have locked down countries over the past few years since Covid-19, he continues, and while Eurobonds defaulted in some African countries, “there have been very few non-payments in trade finance, export finance and project finance and the need for food, fuel, infrastructure and mining finance for critical minerals continues regardless.” With this reminder of the relative safety of trade finance compared with other debt instruments, “we need to reassess the way we look at African risk and we should be able to continue to attract financing into the countries that need it most,” he adds.

Example of an African fishery, supported by the IFC. Photo ©International Finance Corporation

Defaults have not deterred cash-rich corporates from extracting copper in Zambia or coffee companies sourcing beans from Ethiopia. Part of the recovery story of these economies has been adding processing value in-country, creating jobs and getting more currency flowing in the right direction. This has meant investment in plant and machinery – easier said than done when credit ratings are often too far down the alphabet.

Flowing in the other direction, back into a country recovering from economic and/or political crisis, are essentials such as oil and gas, medicines and agricultural commodities such as corn and wheat. “In stricken countries, we will find that when other repayments have been suspended, governments will find a way of making the payments for these key imports,” says Deutsche Bank’s Anand Jha, Head of Trade Finance, Financial Institutions.

Critical pillars

Figure 1: Key facts about multilateral development banks

Source: developmentaid.org

Facilitating trade in frontier economies and after crises is where MDBs and export credit agencies (ECAs) play such a key role. Established in the 1940s, MDBs operate with global and regional remits, working with governments and the private sector (enhanced by their strong credit ratings) to secure finance, typically in the form of loans and grants, to encourage social and economic development – but in a way that does not crowd out the private sector.

Trade facilitation programmes were launched and remain, as Shona Tatchell, the new Head of the EBRD’s Trade Facilitation Program, reflects, “The lifeline that bridges from crisis to normality” (see Figure 1).

The Global Financial Crisis of 2008–09 (GFC), adds Steven Beck, Head of Trade and Supply Chain Finance at ADB (Asian Development Bank), highlighted how “institutions driven by ‘public good’ and development mandates play a critical role in assuring access to adequate levels of timely and affordable trade financing”.

Jha reflects that, “Commercial banks know the requirement of the selling client (for example, a commodities trader) and have a deep understanding of where the goods are coming from – and they also have a relationship with the MDB.” In turn, the MDB has a deep understanding of a country’s financial situation through its relationships with governments and local banks. Once the MDB is comfortable with the country and its economic progress, their guarantees, covering a commercial bank for between 80% and 90% of the risk, make it possible for that bank to provide trade finance.

All three MDBs have clear ESG and sustainability-related finance elements to their programmes. “We believe it is MDBs’ role to standardise the definition of sustainable trade finance. IFC and ADB have published the Sustainable Trade Finance Reference Note4 to provide guidance for banks in emerging markets on the standardised definition of sustainable trade finance, to help promote more sustainable goods trading in developing countries,” says Nathalie Louat, Global Director of Trade and Supply Chain Finance at IFC. “To achieve this, it is crucial that exporters/importers and banks cooperate closely and ensure that necessary criteria are met,” she adds.

More than 15 years after the GFC, the work goes on – although all three MDBs had been supporting trade well before then. Louat points out how current geopolitical tensions and regional conflicts have greatly hampered affordable trade and supply chain finance in the affected countries, “which, in turn, causes severe stress around health and food security”. This is because the countries cannot import food staples or pharmaceutical products. A key inflection point was the Covid-19 pandemic; it was at this time that the IFC approved a US$8bn rapid response package to support emerging markets – US$6bn of which was earmarked for trade finance and short-term working capital finance. ADB’s Beck believes the pandemic has “transformed the global conversation about trade and supply chains” and these are now seen as important elements in solving global challenges such as climate change, social responsibility and resiliency.

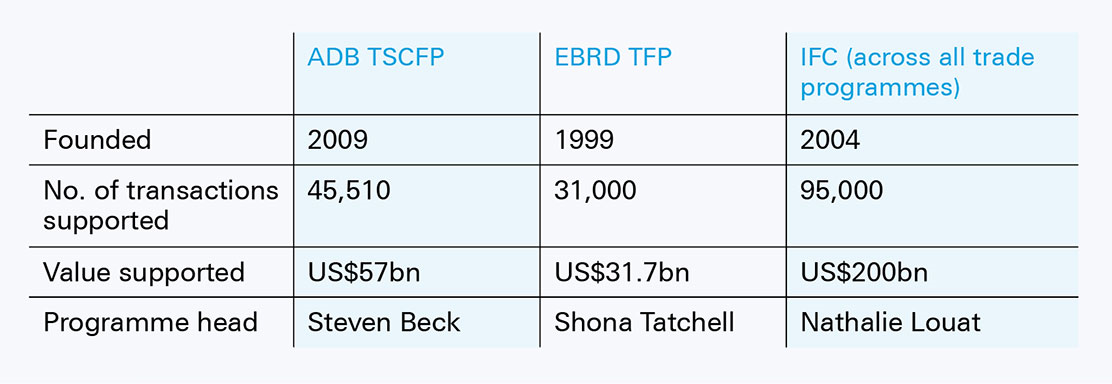

Figure 2: Summary of trade/supply chain facilitation programmes

Note that the sources of data for ADB, EBRD TFP and IFC can be found endnotes 5, 6 and 7

Risk substitution

Where commercial banks find risk challenging, the role of the MDB, explains Tatchell, is to act as the support mechanism for countries and their institutions “to transition into functioning as open, market-based economies with access to clean credit lines, longer tenors and affordable pricing”.

"MDBs help reshape the risk profile of a transaction or trade flow"

It does this, she continues, with credit guarantees, “providing risk substitution through our on-demand 100% coverage guarantees”. Carrying zero-risk weighted assets, these facilitate longer tenor financing and a smoothening of credit pricing. “Our role is also to channel donor funding, both to provide blended finance and grants and subsidies that encourage transition to more sustainable, technologically-enabled economies,” she adds.

In other words, says Beck, “MDBs help reshape the risk profile of a transaction or trade flow so that trade that might otherwise not qualify for trade financing can be supported.” This helps them extend their reach into more countries with more clients “on a substantially risk-mitigated basis”. Louat makes the point that this role of taking on trade finance risk mitigation is not just performed in times of crisis, but is an ongoing “key facilitator of trade finance in low-income countries”.

Closing the trade finance gap

Each year, the ADB publishes its survey-based analysis of the unmet demand for trade finance – the difference between requests and approvals for financing to support imports and exports.8 The gap, as at the close of 2022, sat at US$2.5trn. From Beck’s perspective, “One measure of success is nothing less than having MDBs become irrelevant in financing international trade, because private sector providers would have fully addressed the global demand.”

Obsolescence is hardly around the corner, and the ADB is looking at ways in which the long tail of supply chains could be reached via a potential Deep Tier Supply Chain Finance programme. The gaps, Louat points out, “tend to be more acute for SMEs trying to establish themselves within local, regional or global value chains”.

Tatchell sees the MDB’s role here as one of “training our issuing banks in global expectations of compliance standards, highlighting technological solutions to know-your-customer (KYC), due diligence (DD), Sanctions, and anti-money laundering (AML) screening for our issuing banks and working with confirming banks to demonstrate where our issuing banks should and do meet compliance standards”.

All three MDBs have ongoing dialogues with regulators and standard-setters, with the ICC Trade Register9 (the only authoritative source of industry data on defaults and losses on trade finance) having done much to help reduce the cost of capital associated with providing trade finance.10 It was first launched in 2009 by ADB after Beck first came up with the idea.

Partnerships with Deutsche Bank

Deutsche Bank has a long history of working with all three MDBs, says Jha. Key features of the relationships are:

• ADB: Since 2004, the bank has collaborated on trade finance transactions in countries such as Bangladesh, Pakistan and Uzbekistan. Both Beck and Jha have confirmed the relationship is moving to one based on a risk participation agreement “to foster growth in both transaction volumes and the number of countries engaged”. In September 2023, Deutsche Bank signed a risk participation agreement focused on supply chain finance, extending to three programmes across five countries.

• EBRD: “Deutsche Bank is one of EBRD’s most important institutional relationships,” says Tatchell. Since the partnership began after the fall of the Soviet Union in 1999, the EBRD TFP has supported more than 2,100 transactions for Deutsche Bank, amounting to €1.3bn. These lines have been used for the Caucasus region, Eastern Europe, Central Asia and South-Eastern Mediterranean countries, with Tunisia and Greece being the most common destinations in recent years.

• IFC: Having collaborated on more than US$4.8bn in transactions since 2005, IFC and Deutsche Bank most recently announced a risk-sharing partnership of up to €215m to provide financing to importers and exporters of essential goods in Africa, particularly in small, fragile and conflict-affected states.11

Sources

1 See imf.org

2 See worldbank.org

3 See insight.pangea-risk.com

4 See ifc.org

5 See adb.org

6 See tfp-ebrd

7 See ifc.org

8 See adb.org

9 See iccwbo.org

10 See wto.org

11 See corporates.db.com