08 August 2023

Globalisation is not coming to an end, but a rethink is overdue, Deutsche Bank’s Markus Müller and Marion Laboure argue. flow summarises their thoughts on three acute challenges for global trade: interdependence, technology, and sustainability

MINUTES min read

Swan songs on globalisation have been sung for years – almost decades now. Following the global financial crisis in 2009, world trade has been under stress almost ever since – most recently with the Russia-Ukraine war, inflation and bipolar tensions between China and the USA growing into a perfect storm. Multilateral governance systems are struggling to defend themselves against these headwinds – and, inevitably, this impacts global trade.

So, does this mean political and economic globalisation has come to an end? No, explain Marion Laboure, Senior Economist Deutsche Bank Research Lecturer Harvard University and Deutsche Bank’s Chief Investment Officer ESG and Global Head Chief Investment Office, Markus Müller, in their latest CIO Special Report The great decoupling. “Declaring the end of globalisation is largely hyperbolic,” they state.

Yet, they argue that a rethink of the global trading system is overdue. “Inequality can and has driven anti-globalisation sentiment within economies, whilst rising external trade imbalances have increased international tensions.”

These developments do not only concern policymakers, but the clash between globalisation and national sovereignty has taken centre-stage in the corporate world as well. As the report points out, the number of mentions in corporate documents of keywords such as ‘reshoring’, ‘nearshoring’ and ‘supply chain decoupling’ have increased by more than 240% in 2022.

While production localisation is a fact – and does make sense on the backdrop of increasing supply chain resilience – large-scale decoupling would have tremendous costs. According to IMF estimates, geoeconomic fragmentation could cost 0.2% to almost 7% of global output depending on the severity of the decoupling.1

Hence, Müller and Laboure describe three major challenges to globalisation that need to be addressed:

- Managing high levels of interdependence in a changing global economic and political landscape;

- handling technology, a key driver of change, but also a source of vulnerability; and

- ensuring sustainability by mitigating social and environmental impacts.

Challenge 1: high levels of interdependence

In a complex and connected world, it is necessary to work with countries you do not consider partners but rivals. This becomes particularly apparent when looking at the relationship between China and the US, note the report’s authors. While the two countries are political and economic competitors, they are at the same time dependent on each other both as producers of goods and services, and as key markets for their domestically-produced goods. As the report outlines, the US was China’s most import trading partner in 2022, importing US$564bn which helped to sustain the countries’ export-led growth strategy. Simultaneously, China was one of the largest export markets for American goods and services, consuming US$198bn.

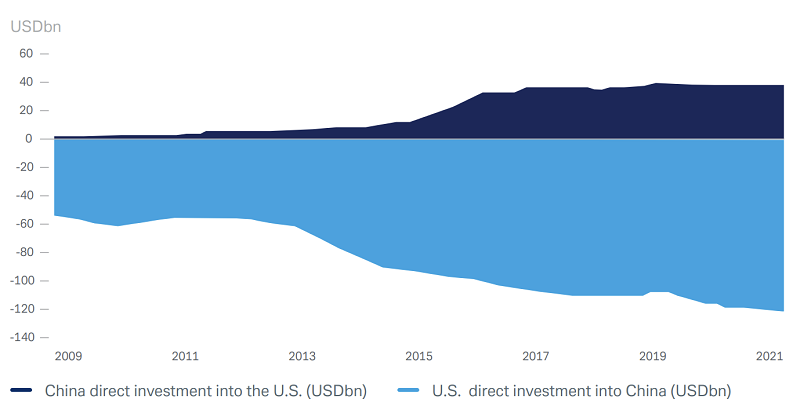

Moreover, bilateral foreign direct investment (FDI) flows have driven investment-led growth in both countries. In 2021, the flow of FDI from the US to China was over US$118bn, while US$38bn went from China to the US (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: US and China foreign direct investment

Source: IMF Coordinated Investment Survey, Deutsche Bank AG. Note: Data is for outward and inward flows to and from China reported by the US

“An economic decoupling of the US and China would cripple the world economy”

Finally, China holds US$859.4bn of US Treasury securities as of January 2023, thereby enabling the cash-strapped US to invest in local infrastructure and other state-driven projects.

Therefore, “an economic decoupling of the US and China would cripple the world economy,” Laboure and Müller conclude, pointing out that lower income countries would likely suffer most. “Third party countries may be forced to trade exclusively with one dominant bloc rather than with multiple trade partners, as is the standard today.” Recent WTO estimates therefore project welfare losses for the global economy of a tech and trade decoupling as high as 12% of GDP losses.2

Challenge 2: technology: dis-integrated circuits

In the past, technology has always been a driver for globalisation. However, on the backdrop of geopolitical tensions, technology is becoming a major point of friction. According to the report, the number of discriminatory or harmful new trade interventions in high tech has increased by nearly 700% since 2009.

To illustrate the effect of these interventions, Müller and Laboure draw on the example of semiconductors – which was the second-most traded product after crude petroleum in 2021, representing 15% of global goods trade. While the US dominates the upstream of the supply chain, possessing the greatest share in advanced chip design, China, on the other hand, mostly produces low-value components in the assembly, testing and package segment of the value chain (see Figure 2).

![]()

Figure 2: Equipment manufacturing in semiconductors

Source: Semiconductor Industry Association. Deutsche Bank AG. Data as of May 2023

Both countries are now seeking to become less dependent on each other. Yet, replacing international supply chains with local ones would take years and come at high costs. “If the US onshored all semiconductor manufacturing, the cost of production for U.S. semiconductor firms would increase by 15–30% due to input cost inflation,” the report says.

China, on the other hand, would have difficulties to expand its advanced chip industry as, on 7 October 2022, the US government released new rules to restrict Chinese access to US made technology, software, equipment and talent used to produce advanced computing chips typically used in advanced military equipment, AI and supercomputers. Moreover, the Netherlands and Japan have also restricted Chinese access to advanced chipmaking equipment.

Geographic choke points add even more complexity: The world’s largest semiconductor company, TSMC, which had a market share of 55% in global chip manufacturing in 2022, is based in Taiwan – a region that is obviously a centre of geopolitical tensions.

Challenge 3: ensuring sustainability for food and energy

Similar choke points exist for food and energy – and some are already closed off: Due to the war in Ukraine, a large portion of global wheat production is at stake. Before the conflict, Russia and Ukraine exported over a third of the world’s wheat, the report points out.

“Food reminds us that supply diversification and supply chain resilience are not equivalent,” Laboure and Müller write. “From the point of view of the importer, specialisation can also lead to a higher dependence on inter-regional food trade. For example, Africa now imports around 80% of its food from outside the region (the EU imports only 26%), making many areas of it more vulnerable to external events.”

Such external events are increasingly driven by environmental developments, the report states. “In many economies, concerns around climate change, fresh-water availability, and biodiversity are not just theoretical: they are making food output less predictable and less sustainable.” The UN estimates that land degradation will cost more than 10% of world annual GDP, threatening 52% of all agricultural land. Thus, sustainability issues must be in the centre of food sectors – which will in turn have effects on global supply chains.

The same goes true for the energy sectors, where concerns about supply insecurity and inadequate local control are also relevant. In this case, the Russia/Ukraine war also illustrated the strengths of globalisation, the authors continue. The EU’s sanctions against Russia led to a de-facto stop of natural gas imports from the country. However, “alternative sources of energy supply were found, and a dramatic (if temporary) rise in energy prices did not translate into major long-term economic disruption.”

This article is a summary of the Deutsche Bank Wealth Management report, The great decoupling? Rethinking sustainable globalisation by Markus Müller, Chief Investment Officer ESG & Global Head of Chief Investment Office, Deutsche Bank Private Bank; Marion Laboure, Senior Economist DB Research, Lecturer Harvard University; Graham Richardson, Financial Writer, Deutsche Bank Private Bank, published in July 2023