September 2020

The traumatic year we’re living through is destined for the history books but may also mark the end of a 40-year economic era, a move away from globalisation, and the start of a more volatile, uncertain period. flow’s Graham Buck assesses the evidence

In Shakespeare’s As you like it, Jaques’ famous monologue describes the “Seven ages of man” from infant through to the final years “Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything”.

Another kind of age – an economic one - has been ushered in by a pandemic that assaults the area of the olfactory nerve (among other parts of the human body) and it was clear within its first few months that the year 2020 had the smell of history about it.

Identifying eras

After the alarms raised by bird flu and SARS, Covid-19 has borne out predictions of a global pandemic by rapidly becoming the most severe global health crisis in 100 years. Coronavirus will also have a more lasting impact and Deutsche Bank Research’s analysts are not the first to suggest that the pandemic has rung down the curtain on one era and marks the beginning of a distinctly different one.

In flow’s ‘Kicking the can: who pays for Covid-19?’ we referenced the just-published leader in the 25 July issue of The Economist1, which stated that Covid-19 had forced a rethink of macroeconomics, whose genesis dated back to the 1936 publication of John Maynard Keynes’s ‘The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money”.

The magazine suggested that three eras had followed: policy guided by Keynes’s ideas that began in the 1940s and endured until the 1970s; the monetarist era that commenced in the 1980s and was associated with the work of Milton Friedman; and finally an approach begun in the 1990s and 2000s in which economists mixed insights from both approaches.

In the 8 September Deutsche Bank Research strategy paper The Age of Disorder, the Bank’s Chief Strategist Jim Reid and colleagues went back further than Keynes to 1860 – and also looked beyond economic cycles – to identify five structural super-cycles that had shaped everything from asset prices and politics to our general way of life over the subsequent 160 years:

- 1860 – 1914: The first era of globalisation

- 1914 – 1945: The Great Wars and the Depression

- 1945 – 1971: Bretton Woods and the return to a gold-based monetary system

- 1971 – 1980: The start of fiat money and the high inflation era of the 1970s

- 1980 – 2020?: The second era of globalisation

Reid and his team believe that 2020 and the disruption caused by the pandemic is hastening the end of the second era of globalisation and we are at the start of the sixth era of this 160-year period, which is dubbed ‘The Age of Disorder’.

Defining features

What is likely to characterise this new period on which the world is now embarking? The report predicts that there will be at least eight major themes to mark the years ahead:

- Deteriorating US-China relations and the reversal of unfettered globalisation.

- A make-or-break decade for Europe, with muddle-through less likely following the economic shock of Covid-19.

- Even higher debt and Modern Monetary Theory (MMT)/”helicopter money” policy becoming mainstream

- Inflation or deflation? As a minimum, it is unlikely to calibrate as easily as has been the case over the past few decades.

- Inequality worsening before a backlash and reversal takes place.

- The intergenerational divide also widening before Millennials (i.e. aged 24 to 39) and other younger voters are in numbers sufficient to win elections and, in turn, reverse decades of policy.

- Linked to the above, the climate debate will build, with more voters sympathetic and thus creating disorder to the current world order.

- A continuation of the technology revolution already underway with “astonishing” equity valuations reflecting expectations for a serious disruption to the status quo. This could either develop as a revolution or a bubble Also, should working from home (WFH) become more permanent post-pandemic, it will trigger major changes to societies and economies. Big cities, which have been huge winners in the previous era, stand to be impacted as this trend could now reverse.

The report acknowledges that while several of the above themes have been around for years “it is only recently that they have begun to feed off each other to hasten the demise of the second era of globalisation”. That era began at the start of the 1980s when the world accelerated the move to abolish regulations and capital controls. The trend gave a boost to free trade and global capital flows, creating a more liberal world order.

Global demographics lent major support to this phenomenon and ensured a huge increase in workforces, many of which were from China and other low-income countries.

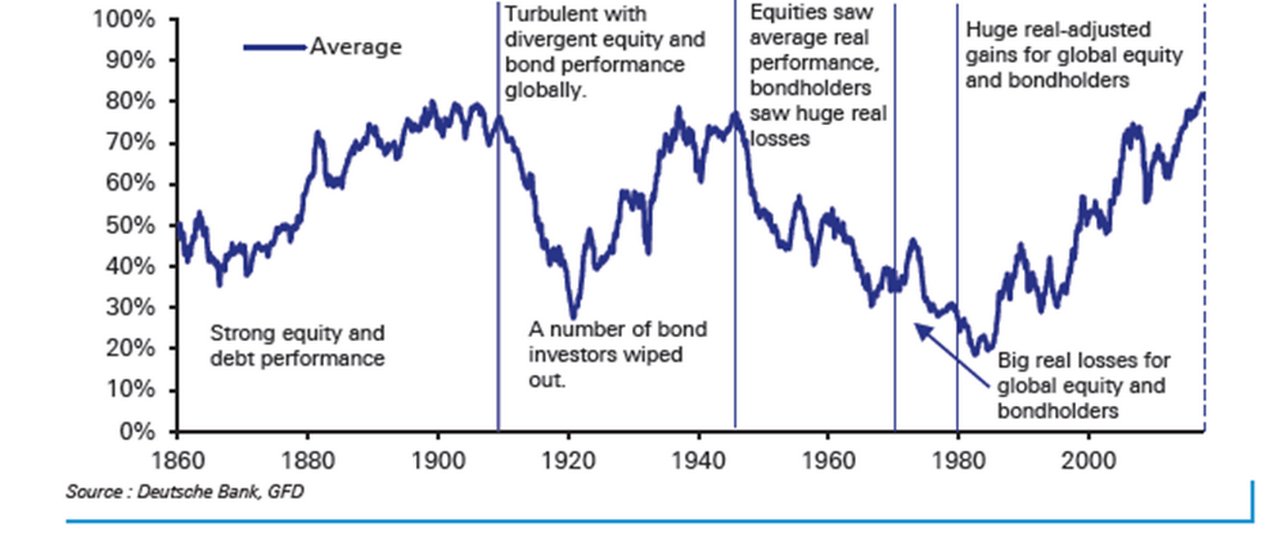

“By the mid-1980s, the second era of globalisation was in full flow,” notes the report and it proved a win-win situation for much of the world over the next three to four decades. The period to the present day has been characterised by falling inflation caused by the huge surge in workers; downward pressure on wage inflation due to global labour market integration and help from direct central bank policy, including increased independence around the world; lower bond yields and lower interest rates; and a generally good performance by equities against what was slowing developed-market growth – see Figure 1 below:

Figure 1: Aggregated 15 DM country average bond (nominal yields) and equity percentile valuations (100% = most expensive; 0% = cheapest)

Source Deutsche Bank, GFDAdd to this the fact that the second era of globalisation has seen a competitive tax environment over the past 40 years, where countries have “conducted a tax arms race to encourage inward investment and jobs,” says Reid – a point emphasised in Figure 2 and also in a report that he and his team issued last December.

“In many ways, the falling corporate tax rate is the ultimate expression of inequality, as it’s been a huge boost for capital over labour,” he adds. “One also has to speculate as to whether it’s part of the reason many countries have been in near permanent budget deficit in recent decades since this arms race began.

“As we try to pay for the cost of the pandemic, and de-globalisation slowly reduces the risk of companies moving jurisdiction, the likelihood is that low corporate tax rates will come under increasing scrutiny.

Figure 2: Global statutory corporate income tax rates (%)

Source: OECD, DeutscheBank, legends ordered high to low for initial 1980 level

End of globalisation

This generally upbeat story only began to sour when the global financial crisis (GFC) hit in 2008-09 and “revealed that ever higher leverage had papered over the problems that globalisation had created in many Western countries”. These problems included sluggish real wage growth, the outsourcing of many lower-paid jobs and increasing inequality. Populism and resentment built in response, as manifested in 2016 by the UK’s Brexit vote and US voters electing Donald Trump. “It was then that most people realised the era of full-feted globalisation was certainly fraying and the problematic issues it had incubated were about to take centre stage.”

“A big part of the problem in business and society is that people still tend to have exaggerated perceptions of how globalised the world is.” noted Professor Pankaj Ghemawat, author of The New Global Road Map, Enduring Strategies for Turbulent Times (2018)2. His insights, first published in 2016 with several revisions and updates ring particularly true now. “This “globaloney” leads to costly business blunders and inflames public anger about international flows. We urgently need a more realistic understanding of the international business environment to inform smarter decisions,” he declared.

As for the forthcoming US election, Reid and his team don’t anticipate its outcome changing the overall “direction of travel” away from globalisation. They note, “ Over the course of this decade, relations will likely deteriorate into a bipolar standoff as both the US and China seek to prevent encirclement by the other. Companies that have embraced globalisation will be stuck in the middle if relations sour as we fear.”

“Globaloney” leads to costly business blunders and inflames public anger about international flows”

A re-think by governments

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development also regards the pandemic as a watershed for economic policy. An OECD-commissioned report released this week calls for governments in developed countries to abandon GDP as the traditional yardstick for economic policy and focus on four main priorities – economic sustainability, improving wellbeing, reducing inequality and strengthening economic resilience.

‘Beyond Growth: Towards A New Economic Approach’3 was commissioned by OECD secretary-general Angel Gurria. Its author, Michael Jacobs, is professional fellow at the Sheffield Political Economy Research Institute (SPERI), representing an international advisory group including Andy Haldane, the Bank of England’s chief economist.

Jacobs’ report agrees that the second era of globalisation has had its day, arguing that “the dominant approach to economic policymaking over the last 40 years, based on an orthodox and subsequently revised model of neoclassical economic theory” no longer fits the task of addressing the “multiple challenges” facing most of the world’s economies.

The contents have more than a tinge of green, warning that “the dominant patterns of economic growth in OECD countries have generated ‘significant harms’ over recent decades – including rising inequality and catastrophic environmental degradation.”

Noting that people have “multi-dimensional preferences and ethics formed in social and cultural settings”, Jacobs proposes an ambitious reform agenda. “So there is a reflexive interaction between individual economic decisions and societal forces, working itself out in social institutions and through political processes,” he writes.

He continues, “This means that our conception of economic progress needs to extend beyond individual, material prosperity to include indicators of social wellbeing, cohesion and empowerment, and the environmental boundaries of human activity. Our frameworks of economic analysis need to acknowledge the social, historical, political and environmental context of economic behaviour, and the feedback loops between individual decisions and societal dynamics which characterise economic systems.”

Not surprisingly, the report concludes that the OECD “has a critical role to play in stimulating understanding and debate about these new approaches” although it’s debatable how much success it can have in the short term if the increasing inequality foreseen by Reid and his team is borne out.

Comparing capitalisms

Having recently proclaimed that Covid-19 has forced a rethink of macroeconomics, The Economist4 suggests in its 11 September edition that the pandemic is also testing the merits of different modes of capitalism.

Its article ‘Which market model is best?’ notes that the various taxonomies used to categorise models include those set out in the 2001 book “Varieties of Capitalism”, edited by political scientist Peter Hall and economist David Soskice. They distinguish between liberal market economies (LMEs) such as the US, Canada and the UK, and co-ordinated market economies (CMEs) such as Germany, the Nordic countries, Austria and the Netherlands.

For Hall and Soskice LMEs’ capitalism is “red-blooded, relying on market mechanisms to allocate resources and determine wages, and on financial markets to allocate capital”. CMEs, although capitalist, “are fonder of social organisations such as trade unions, and of bank finance”, while Western economies “tend to sit on a continuum” between the two. More recently, scholars have also tried to account for the authoritarian, state-driven capitalism of China and some other countries.

The magazine notes that CMEs such as Germany – and also Sweden – are seen as having applied a more coherent strategy in containing the spread of coronavirus. Those of the UK and the US appeared to many as “disjointed and even chaotic” however, as “swashbuckling LMEs” they are “more likely to be the source of the most transformative innovations in the pandemic: treatments and vaccines”. Of 34 vaccine candidates tracked by the World Health Organisation (WHO), four are in CMEs against 13 in LMEs and one (Anglo-Swedish drugmaker AstraZeneca) in both categories. By contrast China is innovative with 10 different vaccines at various development stages but whose “political capitalism” is regarded as suffering from “endemic corruption, self-dealing and lack of trustworthiness”.

The different models of capitalism are also seen in economic trends. LMEs are regarded as better placed to adapt to permanent structural change wrought by the pandemic. Anglo-Saxon firms have moved towards more home working with France and Germany more resistant, while liberal economies have also shifted faster to online retail.

While both LMEs and CMEs have propped up household incomes, China has shown that “under political capitalism the state’s lack of accountability to the public can lead to a disregard for individual welfare in the short term”. So stimulus has focused on promoting investment and construction, with poor households mostly left to fend for themselves.

Post-pandemic, the magazine suggests that every system will have some basis on which to claim victory. CMEs are on course to have lower death counts, China is enjoying a rapid economic rebound, but it is more likely to be an LME found behind the ultimate defeat of the virus. “Life under the liberal model of capitalism can be risky and scary; its failures no doubt cause suffering. But the rewards when things go well can be immense,” it concludes.

Too much debt

In ‘The Age of Disorder’, Reid and his team take the opportunity to drive home points made in earlier Deutsche Bank Research reports about the long-term impact of debt mountains and the cost of intervening rather than allowing market forces to operate.

“A key problem Europe faces is that many of its countries have too much debt, and this leads straight to our third theme in the Age of Disorder. Far from being just a problem in the European periphery, debt is a global issue – and it is only because central banks have distorted free markets that global borrowing can be financed at a viable interest rate. Given central banks have committed to underwriting the post- Covid recovery, they will have an even more outsized role over the years ahead.”

The team believes that Covid-19 has exacerbated this trend “and means we will likely see more crises, more disorder and even more money printing in the years ahead”.5

“A key problem Europe faces is that many of its countries have too much debt”

Climate change: The conflict between the economy and environment

Another important point made in the new report is that 2020 has shown “the world can change, and adapt to that change, far quicker than anyone expected”. This is particularly evident in attitudes to climate change and, note Reid and his team, “Many environmentalists see the virus not as something that will delay their goals, but rather as their biggest opportunity”.

This in itself will usher in more discord between nations, and they predict “aggressive conflict between those who prioritise the economy and those who fight for the environment”, adding, “That conflict will permeate political and policymaking circles and extend beyond national boundaries.”

The team notes that “From a corporate standpoint, climate-change issues are beginning to be driven by customers just as much as investors. Indeed, before the pandemic, the number of people in the UK that actively purchased more products from companies they see as climate-friendly outstripped those who did not by two to one. There was a similar effect in the US.” They add, “Furthermore, boycott culture is becoming more pronounced. About a third of people have stopped buying a product from a company they “really liked” after seeing bad environmental press on the company.”

Trend reversal?

After six months or more of working from home, with many of those still in employment facing no immediate change, the shift in labour and consumption patterns has, note the team, “reached a stage where much of this trend will have an element of permanence”.

This, they conclude “has major implications for cities, residential and commercial property, transport, workers and many ancillary sectors and general activities we've taken for granted over the last several decades”.

As with Shakespeare’s seven ages of man, there appears to be little chance of any going back…

Deutsche Bank Research report referenced:

The Age of Disorder – Long-Term Asset Return Study by Jim Reid, Nick Burns, Luke Templeman, Henry Allen and Karthik Nagalingham (8 September 2020)

Sources

1 See https://bit.ly/2UHMzcz at issuu.com

2 See https://bit.ly/3c4jX3q at ghemawat.com

3 See https://bit.ly/2FCjWb8 at oecd-ilibrary.org

4 See https://econ.st/2ZMBAzQ at economist.com

5 Summarised in our report Central banks: on-side or outside

Go to Corporate Bank EXPLORE MORE

Find out more about products and services

Go to Corporate Bank Go to Corporate BankStay up-to-date with

Sign-up flow newsbites

Choose your preferred banking topics and we will send you updated emails based on your selection

Sign-up Sign-upYou might be interested in

MACRO AND MARKETS {icon-book}

On the bright side On the bright side

Caught in the slipstream, or powering ahead? Dr Rebecca Harding examines ASEAN’s trade momentum in the context of wider geopolitical disruption

flow case studies, Trust and agency services {icon-book}

AstraZeneca and tomorrow’s therapeutics AstraZeneca and tomorrow’s therapeutics

Growing shareholder value and delivering medicines where they are needed most is a tightrope that AstraZeneca has walked for a while. flow’s Clarissa Dann catches up with Andy Barnett, the Anglo-Swedish group’s Head of Investor Relations, about what it takes to maintain investor loyalty over the long term

Macro and markets, Trade finance and lending

No trade, no gain? No trade, no gain?

flow reflects on the seismic changes in the economic world order over the past 12 months, drawing on insights from the Deutsche Bank Research latest Outlook. The focus around inflation and rate cutting remains, centred on the scale of potential US tariffs following the decisive Republican victory on 5 November