26 March 2025

Drawing on a Deutsche Bank Research report examining China’s exports and their destinations, flow’s Clarissa Dann reports on how trade geopolitics are rerouting the country’s trade corridors and what this means for the Global South building its own export capabilities and workforces

MINUTES min read

The challenge of China’s export-oriented economic model is this: 32% of the world’s manufacturing emanates from China, but only 12% of global consumption is China-based. This imbalance between production and consumer demand creates an over-supply of goods in the Chinese economy, which is exported into international markets. This in turn creates a major trade surplus which, in 2024, was nearly US$1trn.

This article summarises insights from the 27 February report, Where will Chinese goods end up?... The answer could change the world, by Mallika Sachdeva, Strategist and Yi Xiong, Chief Economist, China at Deutsche Bank Research.

China’s huge trade surplus is unsustainable in many ways. Western shoppers might have benefitted historically from cheap consumer goods. However, as Chinese manufacturing moves increasingly up the value chain into advanced manufacturing with a higher technology component, Western nations, and especially the United States (US), have raised national concerns. These centre around dependence on Chinese critical minerals, and the need to protect domestic industry from Chinese competition in products such as electric vehicles (EVs).

“Where Chinese goods end up could have a huge impact on the world

The end result is an increase in barriers to trade with China that is redolent of the 1980s competition with Japan. However, the scale of China’s influence over the global trading system means that how this competition resolves itself leads to the rebalancing of global trade, particularly in the Global South.

“Where Chinese goods end up could have a huge impact on the world: from inflation to employment, long-term development and global markets across FX and rates,” explain the report’s authors.

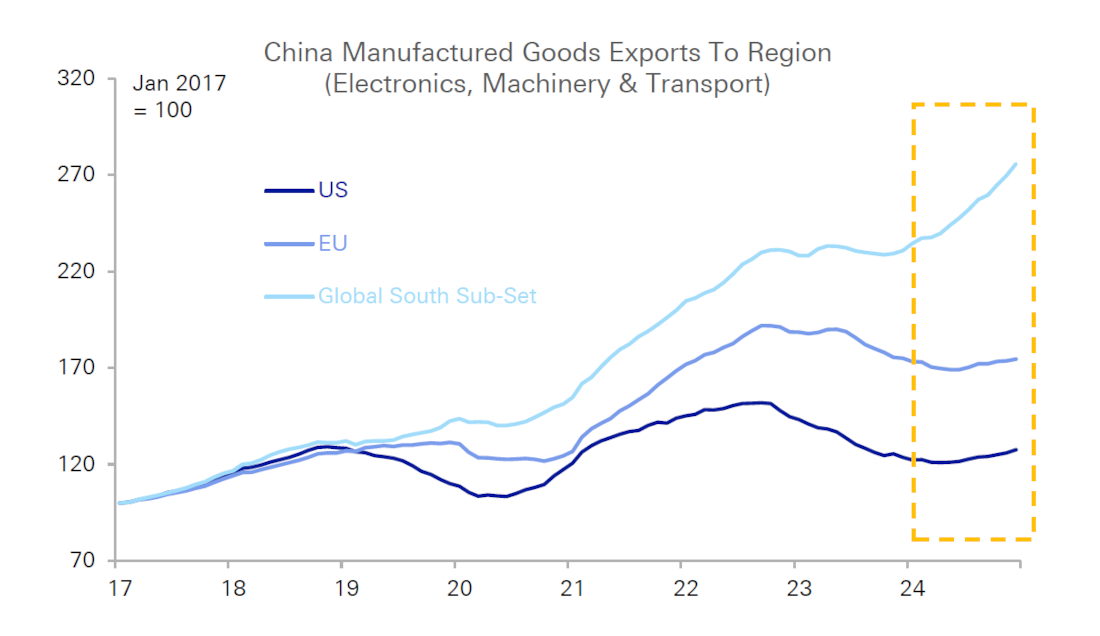

Figure 1: China increases trade with Global South as trade with the West declines

Source: Deutsche Bank, Haver Analytics

The Global South is particularly important in this context because of the role the region’s economies have played over recent years as ‘connectors’ between Chinese exports and their ultimate destination in Western countries. In short, they have taken Chinese exports, very often of intermediate goods, added some value to them and then shipped them on to Western nations. This makes them dependent for their export revenues on Chinese supply chains.

How China’s current imbalances will be addressed in the end will affect the economic development of these Global South countries as well as global patterns of growth, economic development, inflation and employment. The importance of the Chinese economy in the global system means it will also affect financial markets, including currencies, bonds and equities.

The authors see three potential paths going forward:

(1) China increases its domestic consumption

This would mean that Chinese consumers increase their spending on domestic goods, thereby correcting the imbalance between production and consumption. China’s policy makers were focused on this pre-pandemic, based on the purchasing power of its rising middle class.

However, there are several obstacles to this first scenario, not least of which is the high level of production and exports relative to domestic consumption. With an already very high savings rate, and an intrinsic bias in China towards buying services rather than goods, it has proven hard – and will continue in the future – for domestic demand to pick up in the way needed to close the gap. There is another obstacle too: the value of the renminbi (CNY) offers only limited incentives for producers to switch from exporting to selling their goods domestically. As the report’s authors comment, “China's real effective exchange rate (REER) has depreciated by 13% over the past two years, making exports significantly more profitable than domestic sales. Even with a domestic demand recovery, Chinese producers are unlikely to abandon more lucrative export markets.”

(2) China exports more to the Global South

This scenario would embed the distribution of trade that we have seen emerging in the four years since Covid: more than half of China’s trade surplus is now with the Global South and the amounts China trades with these countries has grown by more than US$200bn since 2021. Some of this reflects the impact of tariffs imposed by the US during the ‘trade war’ period of 2018–2019; China has diverted exports through ‘connector countries’. But, as the West raises barriers to taking Chinese goods, and clamps down on connector trade, the Global South may become more the destination than the conduit for Chinese goods.

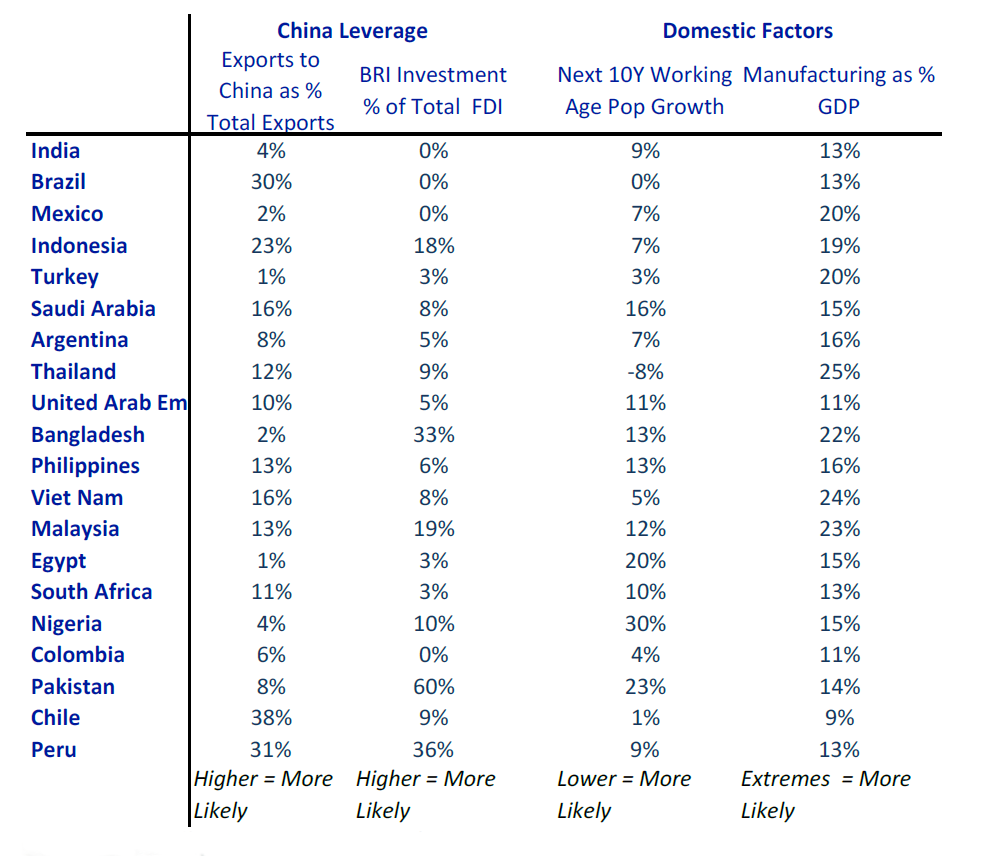

Global South nations have smaller GDPs but by 2050 will account for some 75% of the world’s population, so there is a logic in assuming they will become core consumer markets for Chinese goods in the coming years. This does not necessarily help these economies to develop; and it seems there are two effects depending on the nature of the trade relationship with China:

- Commodity-rich economies have seen their export dependency increase as China has sucked in imports of raw materials. This has not benefited their industrial bases particularly because they have been unable to advance their position in Chinese, or global value chains by producing higher value products.

- Economies integrated into these Chinese value chains as ‘connector economies’ have found themselves dependent for exports on the Chinese export engine itself.

If these economies can grow, then potentially the demands of an emerging middle class, especially in the second group of economies, may be able to buy the cheaper but high-quality goods produced by China. However, there is the risk this could undermine the capacity of their own domestic manufacturing to compete with these low prices putting them over a longer period in the same position as Western economies find themselves now.

Figure 2: Considerations for Global South countries to accept more Chinese exports

Source: Deutsche Bank, Haver Analytics, American Enterprise Institute

(3) China shifts its production to third countries

History offers many examples of major trading powers promoting the development of alternative demand and production centres – whether motivated by geopolitics, trade pressure or economic potential. One could point to US support for Europe's redevelopment after The Second World War under the Marshall Plan. It was in US interest to have an economically stronger Europe, not only as a market for its goods, but to defend against the spread of communism. China, too, may conclude that a stronger Global South in which it invests would better serve its longer-term interests. A more recent and different example is that of Japan in the 1980s. Under significant US trade pressure – culminating in the Plaza Accord strengthening in the JPY – corporate Japan began actively investing overseas, building production bases from the US to emerging markets like ASEAN. China may do the same.

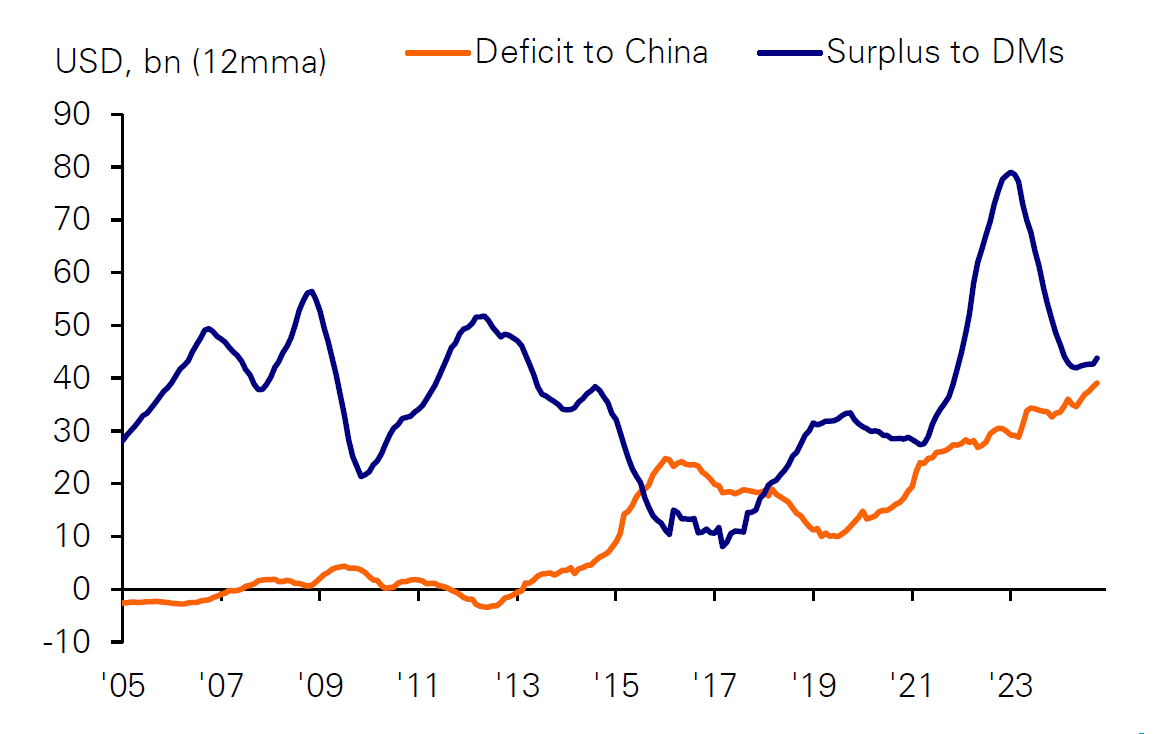

Figure 3: This industrialisation post 2017 is in part explained by an increasing EM trade surplus with DM

Source: Deutsche Bank Research, IMF, Haver Analytics

Before 2017, emerging market (EM) trade surpluses against developed markets (DM) were on a downward trend, but since 2017 both EM surpluses against DM and their deficit against China have increased, with the former increasing faster (see Figure 3). This might suggest that some emerging markets have gradually stepped in to pick up some of China's share as an exports base serving developed markets. Indeed, developed markets, especially the US, have remained a large market for global trade flows; the US trade deficit has continued to grow despite its trade decoupling with China since 2017. This may have created opportunities for other EM exporters to take some China's market share in the US and other Western markets.

"Going abroad" could ultimately be a more sustainable development path for China. Chinese companies invest abroad for various reasons: trade barriers, cost reductions, the need to have local sales/service outlets, and so on. Each decision to invest made by individual companies is likely to be based on a different set of micro-level reasons. But putting these investment decisions together could generate a collective macroeconomic impact, that will create jobs and growth in the recipient economies, and in turn lead to the growth of a large consumer market outside China. The forces that led to China becoming one of the world's largest markets could be at work again in the Global South. If so, it will be good news not only for China but also for the Global South countries.

Figure 3 lists the 20 largest countries in the Global South with considerations that could influence those more likely to accommodate Chinese exports. The factors are manifold, but in some instances the position a country could take is clearer. A country like India – with limited export linkages to China, where Chinese FDI has largely been disallowed in recent years, where the working age population is set to grow significantly and where building out local manufacturing is core to the government's strategy – will be more likely to resist an influx of Chinese manufactured goods.

Currency issues

One final factor that will influence which scenario ultimately unfolds is how the value of the renminbi (CNY) develops over time. The currency has depreciated in recent years from the combination of a weak property market, deflationary pressures, a lack of market confidence in the private sector and significant capital outflows. If it remains weak, the extent to which the Chinese economy can base its production on strong domestic consumption is questionable.

But if China’s manufacturing productivity improvement is maintained, economic theory would predict that China’s ‘Real Effective Exchange Rate’ (REER) should eventually appreciate, similar to what happened between 2005 and 2015, to equalise the prices of Chinese and non-Chinese products on the international market. A stronger currency would favour more domestic consumption, increasing Chinese purchasing power, creating demand for goods from overseas, and narrowing China's trade surplus. It will also strengthen the trend of Chinese companies shifting productions and operations abroad on cost grounds.

Deutsche Bank Research report referenced

Where will Chinese goods end up?... The answer could change the world (27 February 2025) by Mallika Sachdeva, Strategist and Yi Xiong, Chief Economist, China at Deutsche Bank Research