16 July 2025

flow’s Clarissa Dann explores how project financing supports essential infrastructure and energy projects around the world

MINUTES min read

According to the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), by the end of 2024, renewables accounted for 46% of global installed power capacity. Yet this growth is not enough to triple installed renewable power capacity to 11 terawatts (TW) by 2030. To meet this goal, which was established in December 2023 by nearly 200 countries at the COP28 climate summit, the world now needs to add in excess of 1,120 gigawatts (GW) each year for the rest of this decade.

“Looking ahead, we need to see a much faster pace of growth in the stock of renewable power plants and distributed electricity generation around the world,” said IRENA’s Director General, Francesco La Camera, in the agency’s Renewable Capacity Statistics 2025 report.1

The challenge that many economies face is how they convert ambitious renewable infrastructure targets into reality. Such projects tend to be capital-intensive and come with long-term risks. Take the example of a large-scale solar farm: the project would likely take one to two years to build and, even after completion, could take many more years to generate the kind of revenue that returns the initial investment.

Whether it’s building roads or hospitals, replacing ageing infrastructure, upgrading transport networks or accelerating the pace of renewables installation worldwide, project financing is well placed to help fund large-scale, capital-intensive projects.

What is project finance?

Project finance is a method of funding a single asset or a group of similar assets. Unlike traditional corporate loans, which are secured by a company’s overall balance sheet, project finance relies solely on the cash flows generated by the project itself to repay debt and service equity. In the case of a highway, this may come from toll revenues, or for a hospital from availability payments, while for a renewable energy project, repayment would come from the sale of electricity.

Since repayment comes directly from the assets, project finance imposes stricter controls and more tailored restrictions than a traditional corporate loan. A corporate loan, for instance, is issued at the company level, usually for the short to medium term – and is structured with covenants linked to the company’s overall financial position. In contrast, project finance – due to the focus on the project’s future cash flows – has covenants designed to ensure that the project can generate sufficient revenue to cover its debt obligations.

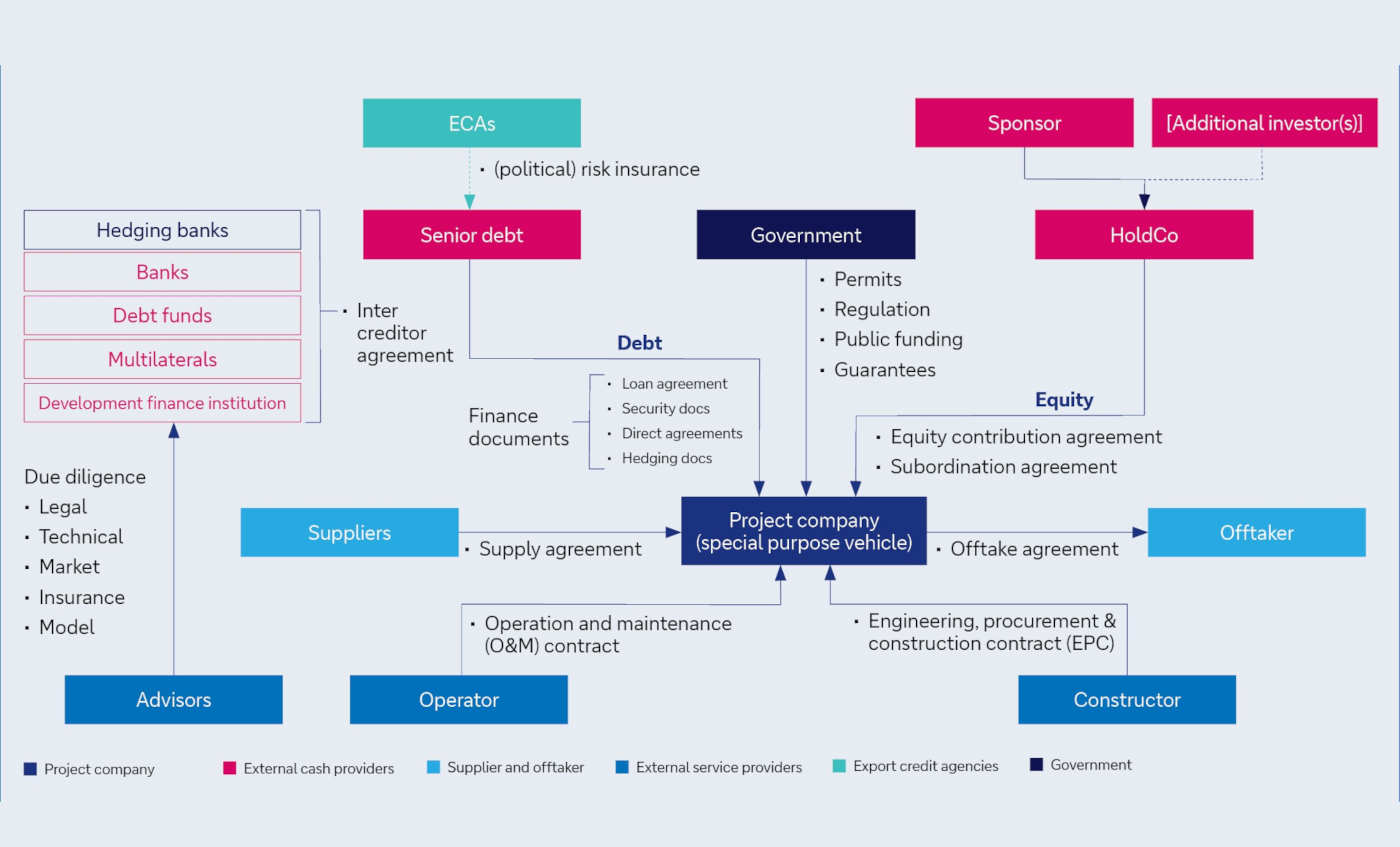

To ensure that proceeds from the project go towards repaying investors, the project’s sponsor – responsible for its initiation and organisation – establishes a project-specific entity, usually in the form of a special purpose vehicle. This serves as a standalone entity, isolating the project’s financial risk and ensuring its financials are kept separate from the sponsor’s broader activities. This type of non-recourse or limited-recourse financial structure is what helps enable project financing to support complex and riskier projects.

The initial financing for the project typically then comes from two main sources: project sponsors, who can provide equity financing to support it, and lenders – such as financial institutions – who provide debt financing through long-term loans or bonds. Governments can also play a role in this financing ecosystem. They may support projects through export credit agencies, which provide guarantees to lenders, or offtake contracts, which guarantee the purchase of the project’s output – providing additional security to investors.

Figure 1: Illustrative business structure from a project financing perspective

Source: Deutsche Bank

How banks manage project risks

While the underlying concept is fairly simple – providing the capital needed to finance an essential project – project financing involves a highly complex decision-making process. Lenders perform rigorous risk assessments to determine the viability of the project. At a macro level, the first consideration is the risks associated with the country in which the project is being developed – reviewing how existing policy and regulation might impact the project, as well as the risk of legal changes, incoming tariffs or even the onset of war or civil unrest.

A key element in ensuring a steady revenue stream and the long-term viability of the project is the presence of a reliable offtaker

The technical and design feasibility of the project will also be carefully evaluated. For example, in an offshore wind project, lenders must ensure that the turbines are reliable and suitable for the specific environmental conditions.

The practicality of construction is another important area, particularly for greenfield projects, which involve building entirely new infrastructure rather than upgrading existing assets. Construction risks can include cost overruns, issues with obtaining necessary permits or land, and delays to the completion date – all of which can impact the expected cash flows from the project.

Lenders will also consider the long-term operational risks involved, including the reliability of the project operator, as effective maintenance and management directly influence the asset’s long-term performance. Equally important is ensuring that the necessary resources are consistently available to support both the completion and ongoing operation of the project, avoiding any potential disruptions.

Banks must ensure that projects adhere to environmental regulations, including the Equator Principles – the risk management framework for responsible investment.2

As cash flows from the assets underpin the financing structure, a key element in ensuring a steady revenue stream and the long-term viability of the project is the presence of a reliable offtaker – a party committed to purchasing the project’s output for a set period. For projects such as wind farms and solar plants, this often takes the form of a long-term power purchase agreement.

Transaction highlights

Three recent project finance transactions show this structure works in practice:

During Q1 2025, Deutsche Bank acted as mandated lead arranger in a €2.9bn non-recourse project financing for Polska Grupa Energetyczna SA (PGE). At 1.5GW, Baltica 2 is the biggest offshore wind farm project currently planned in Poland, developed jointly by PGE and Danish offshore wind power energy company Ørsted, and will produce green electricity to meet the needs of around 2.5 million households.3

On 7 April 2025, Aukera Energy, the pan-European renewable energy developer, announced that it had secured a £135m senior debt facility from Deutsche Bank and Rabobank to finance the construction of five UK solar PV projects, expected to be fully operational before the end of 2026. Pascal Emsens and Catalin Breaban, Aukera’s co-founders, said, “It has been fantastic to see this team working together so effectively to deliver this complex and efficient financing. It has been a pleasure to work alongside the excellent teams at Deutsche Bank and Rabobank to deliver this transaction, marking the beginning of Aukera’s next stage of growth as our project pipeline starts to reach maturity in all four of our markets.”4

On 21 January 2025, Australia’s Quinbrook Infrastructure Partners announced its new debt financing – to the tune of AUD722m – for Stages 1 and 2 of its Supernode battery storage project in Queensland; one of Australia’s largest stand-alone battery energy storage system (BESS) project financings to date. Deutsche Bank acted as lead arranger, original lender and hedge counterparty. Quinbrook has secured long-term offtake agreements with Origin Energy for Stages 1 and 2 for a combined BESS nameplate capacity of 520MW/1856MWh.5

Sources

1 See irena.org

2 See equator-principles.com

3 See the Sustainable Finance section in the 29 April Deutsche Bank Q1 report at db.com

4 See aukera.energy

5 See quinbrook.com