13 November 2024

Following the decisive election victory for the Republican party on 6 November, what does the win mean for US trade relations and, more widely, for the future of multilateral trade? Independent trade economist Dr Rebecca Harding finds answers in US import and export data

MINUTES min read

With the election of President-Elect Donald Trump (‘President Trump’ hereinafter given this is a second term), trade policy is about re-assert itself on the US government agenda. While the Biden administration did not sign any trade deals, it was not passive about trade:

- Tariffs were kept on Chinese imports that President Trump had introduced during his first administration;

- Biden’s CHIPS and Science Act and the Inflation Reduction Act both provided significant financial incentives for business and financial institutions to relocate their research and development and production to the US; and

- The restrictions on the use of US technologies in Chinese products were significant means of excluding China from US supply chains.

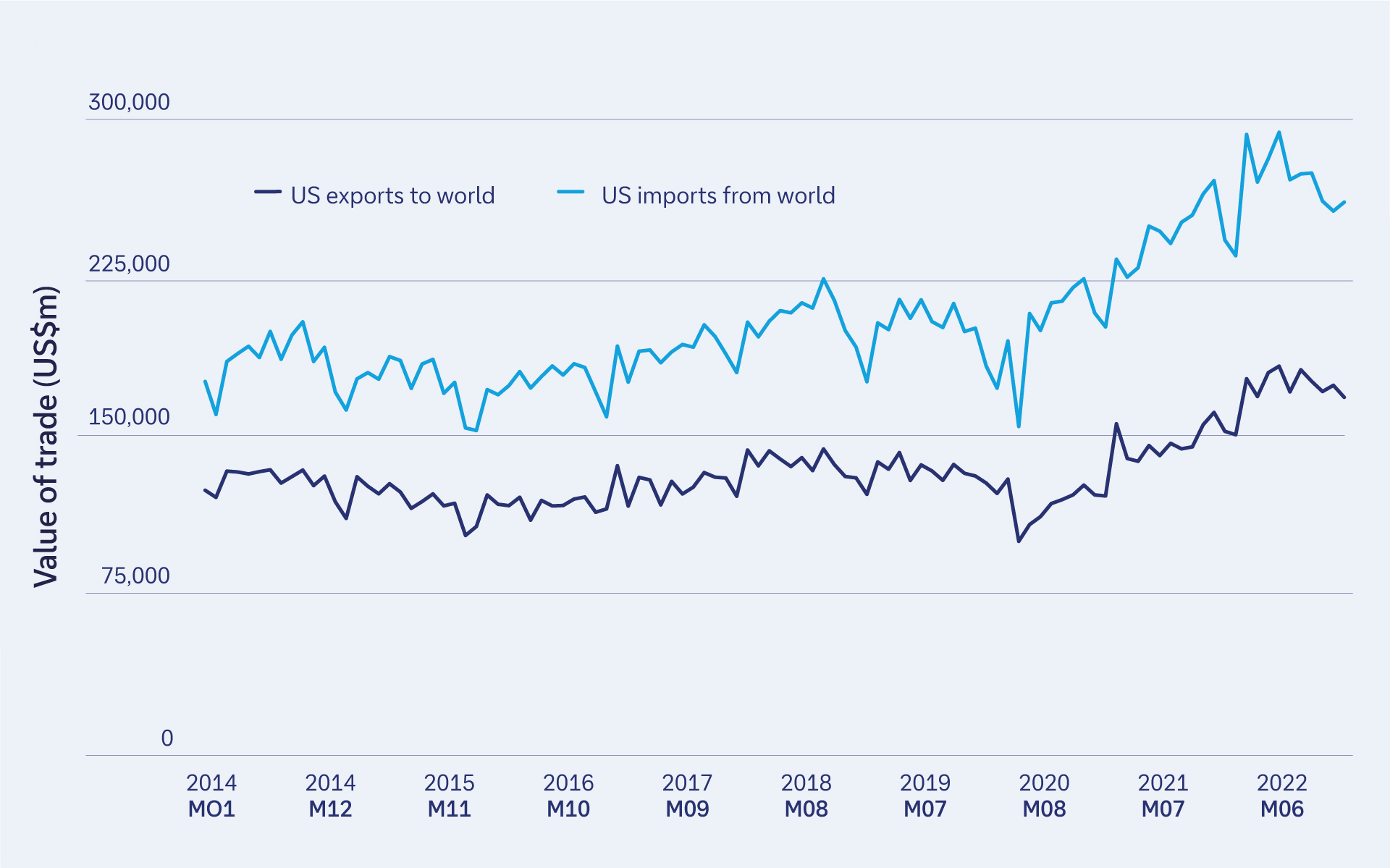

Widening US trade deficit

We can, nonetheless, expect a major shift in policy. President Trump has an overtly nationalist and transactional approach to trade that will rely heavily on tariffs to reduce the size of the US trade gap with the rest of the world generally – and particularly with China and the EU. The US deficit, including services, stood at -US$84.4bn in September 2024; the merchandise goods trade balance was -US$108.2bn, which was the highest for two years.1 Figure 1 illustrates how the trade deficit has been widening, particularly since 2020 and the onset of the pandemic.

Figure 1: US trade with the world, US$m

Source: IMF Direction of Trade Statistics (downloaded, November 2024)

As the means to deal with this deterioration, President Trump has already signalled a blanket increase in tariffs for goods going into the US of 10% upwards, with a 60% tariff on Chinese goods.

There are undoubtedly inflationary effects of an increase in tariffs both in the US itself and around the world. In May 2024, Deutsche Bank Research estimated a rise in inflation of anything between 0.75% and 2.5% if fully implemented.2 Equally we can expect a more fraught relationship with the EU3 resulting from an “America First” agenda, which is almost by definition protectionist in nature. It may also contain non-tariff barriers to non-US products, including incentives to “buy American” and “build in America”, such as on-shoring and the re-negotiation of “unfair trade deals”.4

“It is possible that the new US administration will not be that different in terms of direct [trade] action to its predecessor

Two things are worth bearing in mind, however. First, the second Trump presidency is much more of a known quantity than the first, and second, under the Biden administration, the US has put significant pressure on the rest of the world to reduce its exposure to Chinese markets; most recently evidenced in its focus on the Dutch semi-conductor manufacturer, ASML.5

This time around, President Trump also has a clear electoral mandate which may embolden the rhetoric around tariffs. However, experience suggests that there is an equally strong likelihood that this is a negotiating tactic. In other words, it is possible that the new US administration will not be that different in terms of direct action to its predecessor.

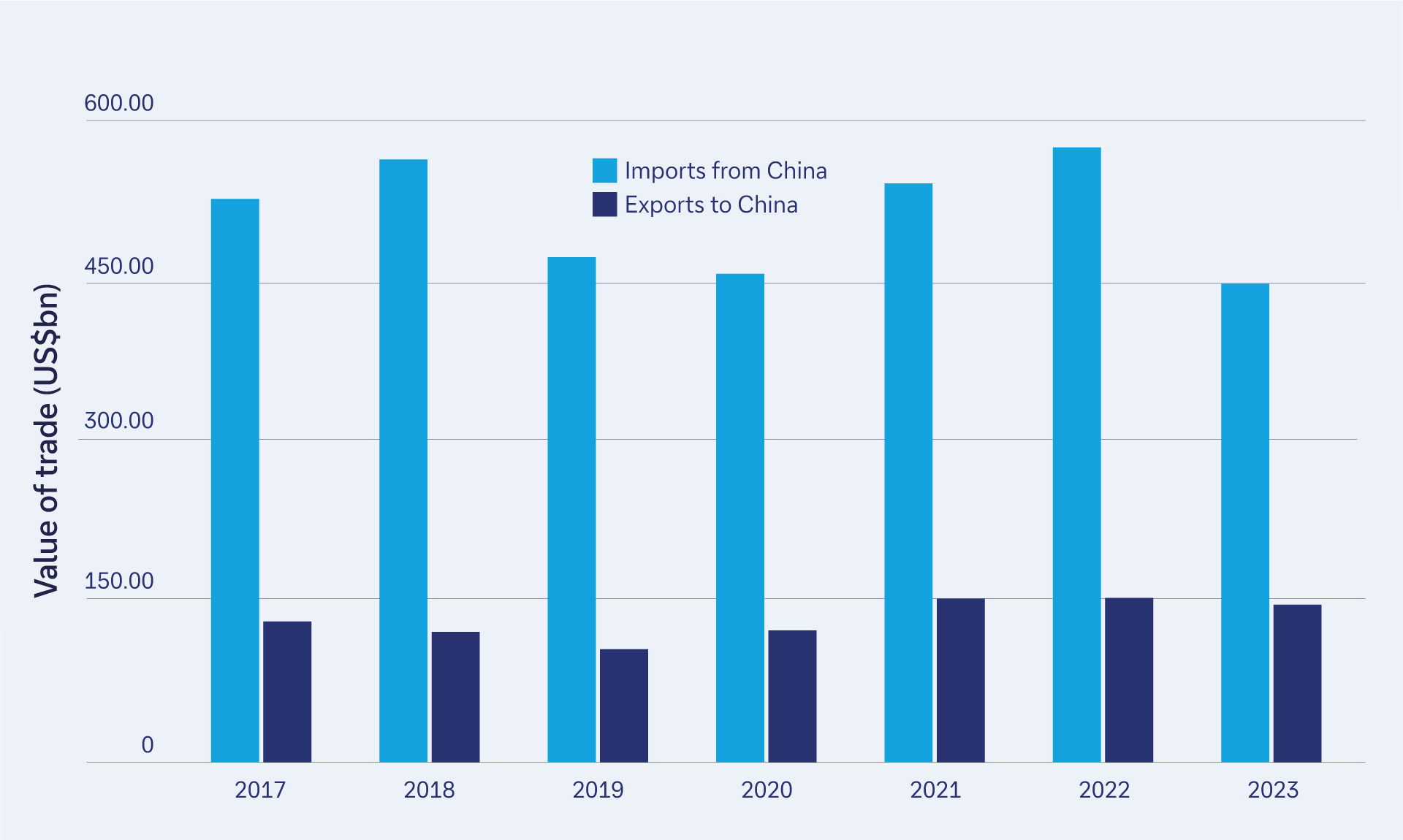

There are very good reasons for this premise that are illustrated through an analysis of the US trade deficit and its relationship with China. Since 2017 the size of the budget deficit with China has fallen at an annualised rate of nearly 6%, as illustrated by US exports to and imports from China (see Figure 2).

Tariffs on China were first introduced in 2018 and there was an immediate drop in trade between 2019 and 2020, which included the pandemic and supply chain shortage effect. However, after 2020, trade with China grew in terms of both imports and exports, suggesting that the tariff regime itself was having little effect. President Biden’s more restrictive industrial strategy measures to restrict Chinese trade did not start until October 2022 and it has been since then that the sharpest reduction in trade has happened, even if the deficit has not closed. These restrictions will continue and have in fact become more stringent since October 2024 in relation to artificial intelligence (AI) technology.6

Figure 2: US trade with China, imports and exports, 2017–2023 (US$bn)

Source: United Nations Comtrade, November 2024

Technology trade controls

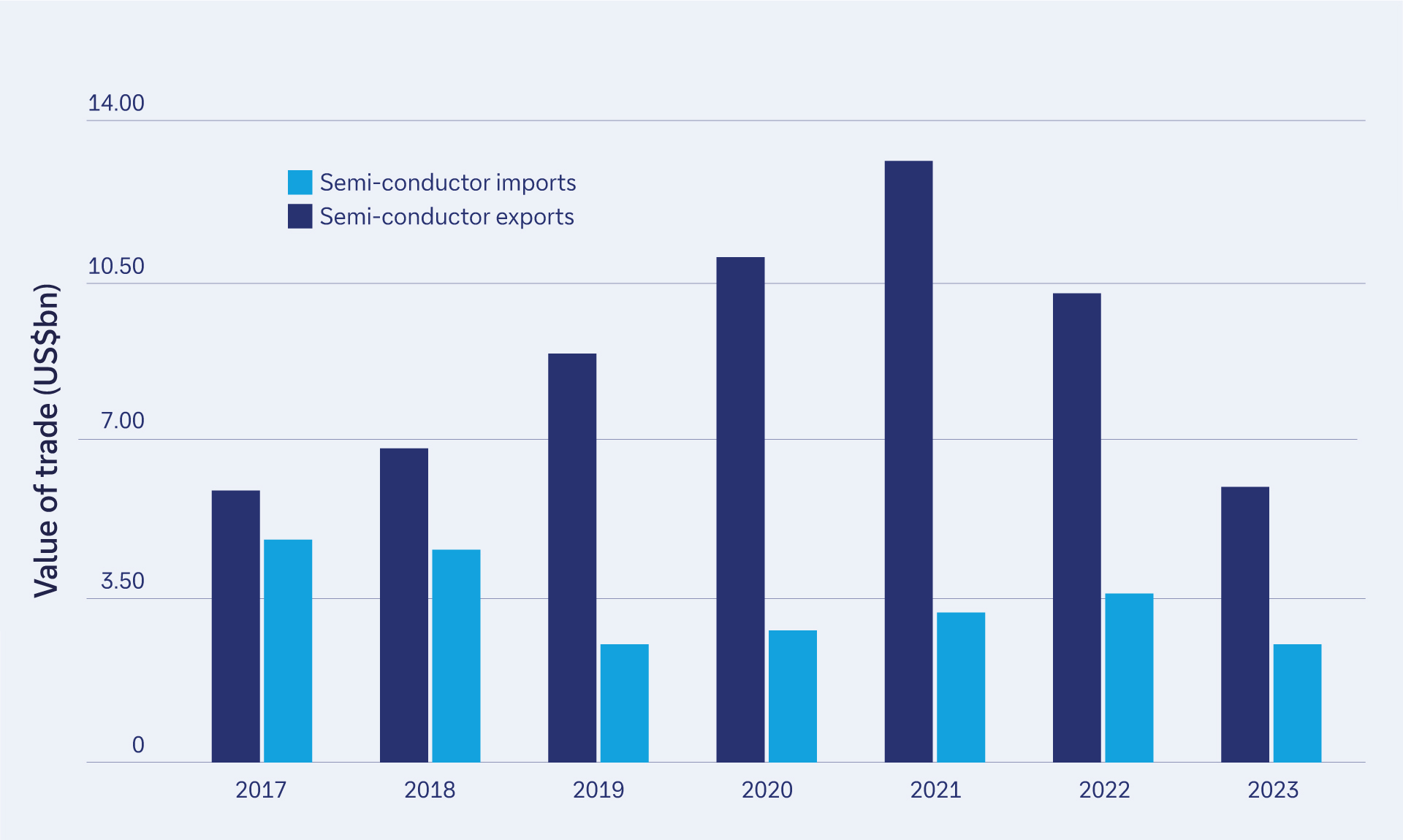

The effect on technology trade of these industrial strategies has arguably been significant. Figure 3 shows US – China trade in semi-conductors broadly over the same period.

Figure 3: US semi-conductor trade with China, imports and exports, 2017–2023 (US$bn)

Source: United Nations Comtrade, November 2024

It highlights how the US does not have a trade deficit in semiconductors, so it can use its exports to reduce access to its technologies. The chart above suggests that the federal rules, executive orders and legislation programme since 20227 to reduce this access has had an effect both on imports from and exports to China of semiconductors. Exports over the whole period have shrunk by around 2.6% annually. Similarly, the combination of tariffs, retaliatory measures from China and semiconductor supply chain issues has reduced Chinese imports at an annualised rate of over 11% over the same period.

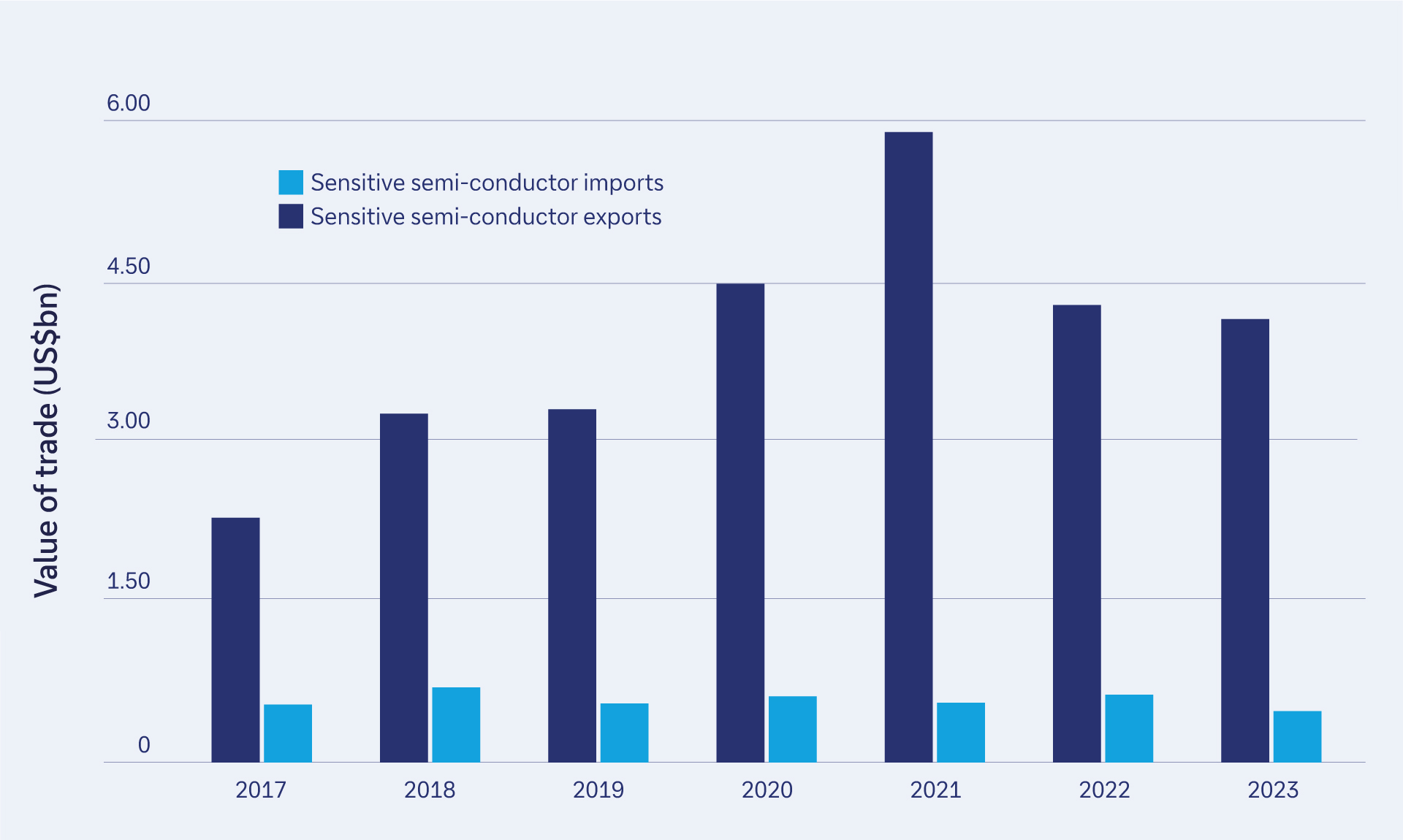

One key goal of the Biden administration over the past two years has been to reduce Chinese access to military grade technologies and this has had a very mixed effect (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: US semi-conductor trade with China, imports and exports, 2017–2023 (US$bn)

Source: United Nations Comtrade, November 2024

Since 2017, while Chinese imports of sensitive technologies have reduced significantly at an annualised rate of 6.7%, US exports to China of these technologies have actually increased at a rate of over 5% annually. That is, while US exposure to Chinese manufactured military grade semiconductors has fallen, exports have actually grown, with a strong spike between 2019 and 2022.

President Trump has a very clear focus on intellectual property and is unlikely to reverse the technology controls on US-China trade that have been implemented by the Department of Commerce over the past two years. The effect of tariffs is less clear cut – it may have contributed to a slowing of trade but by themselves, tariffs were not solely responsible for reducing the US trade deficit with China, nor did they address slow trade in sensitive technologies.

“The world is not in the same place that it was in when [President Trump] was first in power”

New world trade order

These recent trends point to an important consideration when it comes to how President Trump will handle trade relations in the next four years. The world is not in the same place that it was in when he was first in power. The Russia/Ukraine war, conflict in the Middle East and an ambiguous role for China in relation to Russia have worsened the geopolitical climate. Alongside this there is a greater degree of fragmentation in the trade system, with more trade disputes taking place outside the framework of the World Trade Organisation (WTO) than at any time, and many now suggesting that the “liberal trading order” is in crisis.8

Again, looking at what the second Trump administration would do compared to previously might suggest that perhaps less will change than is expected:

- The WTO has been weakened during the first administration. It has not reformed over the past few years to withstand pressure on the multilateral trading system – the challenges around e-commerce and digital trade tariffs at the 13th Ministerial conference in 2024 exemplified the difficulties of this, not just from the US but also from countries such as India.9

- The Biden administration did not restore the WTO appellate body to rekindle its dispute resolution system. Creating further challenges through the multilateral trading system that the WTO represents will be hard to do without actually leaving it. This may not be necessary in a second term, as much of the damage to its structures and relevance has already been done.10

- The consistent declaration by the US of ‘unfairness’ in the global trading system against US interests has not abated. President Trump’s former Trade Representative, Robert Lighthizer argues that the global trading system is at fault for the deficit situation that America now finds itself in,11 and that tariffs will not create inflation but will support US jobs and manufacturing.

- However, any existing “unfair” trade deals are ones that have been negotiated by President Trump himself. As noted earlier, the Biden administration did not sign any additional free trade deals and focused instead on tightening trade restrictions in specific sectors and using trade negotiations to focus on critical supply chains.

Outlook for key trading relationships

Mexico and Canada

The US-Canada-Mexico (USCMA) deal is to be renewed in 2026 and its impact on jobs and regional growth already appears to have been significant. “Impressive growth in trade over the past two years has made Mexico and Canada the top trading partners of the United States, with trade volumes 44% higher than U.S. goods trade with China,” noted the Washington DC-based Brookings Institution on 19 July 2024.”12 Perhaps its most important impact has been on deepening the trading relationship across the key countries in a way that supports resilience in critical minerals, climate change and clean energy supply chains. It would be hard for President Trump to undo his own work if it continues to be successful.

Europe

For Europe, there are substantial consequences of a more aggressive trade stance by an American regime focused on re-shoring and building capability domestically. The US is a major market but while there is a trade deficit of US$131.3bn, as there was in 2022 following the Biden legislative programme, the US may well seek to negotiate a redress of the balance. Although trade disputes have dominated the headlines in US-EU trade relations, the EU itself argues that these only affect 2% of trade between the two blocs.

Nonetheless there are tensions and in recent years the EU-US Trade and Technology Council has perhaps not achieved its objectives of creating a harmonised approach to technology,13 and the differences between Europe’s integration and inevitable multilateralism were not replicated in Washington – despite the warmer words of the Biden administration. In September 2024 an article in The Atlantic Council opined, “A comprehensive transatlantic economic agreement—not a traditional trade agreement—could avoid relitigating the issues that have sunk past US-EU trade and investment initiatives.”14

Much of the relationship between Europe and the US will be strongly determined by the way in which the US’s relationship with China evolves over the next four years. Many assume that the administration will be more aggressive towards China, not just in imposing tariffs but also removing its Most Favoured Nation (MFN) tariff status at the WTO.15 This would materially affect Europe as well and alter the freedom with which technology and investment – as well as goods and services – could flow between countries trading in the US dollar and China.

China

The Trump administration will also see its trade agreement with China as unfinished business. China’s economy is weaker than it was during Trump’s first term and the new US trade representative will undoubtedly look to create a second deal that is tighter than the first. The EU should not expect that the relationships will improve between the two nations; indeed, its own position towards China has tightened in the last two years with the imposition of tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles for example. However, EU-China trade was worth €739bn in 2023 and Chinese products are deeply integrated into EU supply chains.16 The effects of Trump 2.0 will be felt not just through any potential tariffs but also through the spillover effects from a potential trade war with China.

'America first’

It is worth underlining the main point here: that the fragmentation of global trade is a trend that has been gathering pace since 2016. President Trump’s first administration and the subsequent Biden administration have taken similar approaches in recent years and reinforced the America First agenda underpinning much of US trade policy over that time. Broader geopolitical and geoeconomic factors are adding to the complexity of global trade as it goes through an era of rapid change. At the very least there will be fewer surprises with a second Trump administration – this really does feel like ‘Back to the Future’.

Insights on US election from Deutsche Bank Research

President-elect Trump has been clear about his policy agenda of tax cuts, tariffs, deregulation and immigration policies. However, the sequencing between fiscal and trade policies and the tactics around tariffs remain critical and uncertain. Our assumptions around these key parameters include the following:

- Fiscal: Tax policy is prioritised. The Tax Cuts and Job Act (TCJA) is extended and additional tax-cut measures are enacted (e.g., the corporate tax rate cut to ~15%, possibly Child Tax Credit (CTC) expanded) but other proposals are not pursued (e.g., no change to state and local property tax deductions (SALT) and no exempting the following from taxes: social security benefits, tips, overtime pay, etc). To be sure, domestic tax policy priorities could shift as the full year 2025 budget process takes shape.

- Trade: A trade war occurs but tariffs are not implemented until H2 2025 into 2026. Consistent with the approach to the first trade war, we expect various tariffs to be phased in over time contingent on negotiations meeting certain benchmarks (i.e., potentially 50-60% tariffs on China, tariffs on Europe and any universal baseline tariff start lower and ratchet up over time if no agreements are reached).

- Immigration: Border controls are strengthened but broad-based deportations are not pursued.

- Fed: Monetary policy independence is not seriously challenged, Fed Chair Jerome Powell serves out his term, and conventional candidates are appointed for key spots, most notably Fed chair. A risk scenario would be if large budget deficits combined with challenges to Fed independence lead to a material rise in term premia, which tightens financial conditions and ultimately causes a moderation in policies.

From ‘US Economics Perspectives - Post election: Fiscal fuel trumps trade tensions for Fed by Matthew Luzzetti et al, Deutsche Bank Research (6 November 2024)

Sources

1 See tradingeconomics.com

2 See ‘US Economic Perspectives: Trade war II: Supply-side risks versus revenue rewards’ by Matt Luzzetti, et al, Deutsche Bank Research, 29 May 2024

3 See politico.eu

4 See blogs.lse.ac.uk

5 See reuters.com

6 See reuters.com

7 See politico.com

8 See foreignaffairs.com

9 See whitecase.com

10 See foreignaffairs.com

11 See ft.com

12 See brookings.edu

13 See policy.trade.ec.europa.eu

14 See atlanticcouncil.org

15 See hinrichfoundation.com

16 See theconversation.com