26 July 2023

The ASEAN countries are a vital part of the global economy. flow takes a closer look at the bloc’s growth, current status, and prospects

MINUTES min read

The Buddha noted that “If we could see the miracle of a single flower, our whole life would change”. Underpinning the East Asian Miracle, as described by the World Bank in 1990,1 have been “rapid demographic transitions, strong and dynamic agricultural sectors, and unusually rapid export growth”. The economic bloc comprising The Association of South-Eastern Nations (ASEAN) provides an ongoing example that this continues today.

Where you will find ASEAN exports

This general lack of awareness relates not just to the growing ubiquity of ASEAN products and services – whether commodities or hi-tech – but also to ASEAN capital, whether deployed within the bloc or beyond. For example:

- The Australian parent putting chocolate spread on their child’s toast before pouring themselves a coffee will likely find Indonesian cocoa beans mixed into the former, and Vietnamese arabica coffee beans in the latter.

- The South American student who checks the details of their journey on their mobile phone before boarding a bus will likely find semiconductors made by Infineon Technologies in Malaysia in both the phone and bus, and that the Mercedes bus was designed and manufactured using software designers based at a shared-service centre in the Philippines.

- The North American retirees who go for a weekend’s gambling and concerts at any of the Resorts Worlds across the US, and the British parties who visit any of the Genting casinos across the UK for a flutter and a meal, will all have enjoyed the facilities and hospitality of a Malaysia-headquartered leisure giant.

- The African tourist on holiday in London who enjoys a Chang beer at a bar after a hard day’s retail therapy at Battersea Power Station will have experienced a beverage brewed in Thailand, and the shops in a retail development made possible by a consortium of Malaysian investors led by S P Setia and Sime Darby Property.

- The Indian co-workers in Amsterdam celebrating a business deal with a seafood dinner while staying at the Grand Hotel Krasnapolsky will likely eat prawns from Vietnam, in a hotel chain owned by the Thailand-based Minor International. The latter owns a host of other global businesses besides the NH Hotel Group, including many across the US, such that the trucker stopping for a snack at a Dairy Queen in Nebraska or the banker wearing a Brooks Brothers shirt in Manhattan will both have enjoyed products made possible by Thai capital.

As Burkhard Ziegenhorn, Head of ASEAN at Deutsche Bank’s Corporate Bank, notes, “ASEAN is benefiting from strong consumer market growth.” He continues, “We are talking here about the real economy – for example, companies going abroad and setting up semiconductor chip factories in Malaysia, or other companies exporting frozen fish and seafood from Vietnam.”

Deutsche Bank’s ASEAN portal already contains an introduction, published in July 2021, to Doing business with ASEAN. Three other analyses can be found there on Indonesia, the Philippines and Vietnam; further ‘deep dives’ on Malaysia and Thailand are planned. This article takes a closer look at the current status of ASEAN economies and the macro and business themes that will drive their future direction.

“ASEAN is benefiting from strong consumer market growth”

ASEAN’s economic development provides a shining example to other parts of the world with its rapid progress from low-income to middle/high-income economy status.

In particular, the transformation is noteworthy as a model to other regions because it did not happen through aid or philanthropy, but rather through foreign direct investment (FDI), supporting enterprise, and good old-fashioned hard work. Indeed, the examples provided above of intra-ASEAN FDI are nothing new and are actually how the East Asian Miracle came about.

As Japanese companies sought to establish manufacturing plants overseas, they were welcomed by ASEAN governments, since they would provide both jobs and training in new technologies. In short order, these Japanese-trained people in ASEAN host countries established their own businesses – some supplying their previous patrons, others competing directly with them. In addition, China’s influence in the region continues to grow – the high-speed trains in Laos connecting the border of Thailand to Southern China being just one example of RMB investment. China is currently ASEAN’s largest trading partner and the second-largest source of FDI, with the prospective upgrade of the ASEAN-China Free Trade Agreement looking set to maintain this momentum.2

“While data suggests that ASEAN’s role has broadened in the last decade, it also points to China’s continued central role in global manufacturing. The Covid pandemic also revealed the relative integrity of China’s manufacturing ecosystem and the world’s continued dependence on it,” comments Deutsche Bank Research Asia Chief Economist Juliana Lee.3

Malaysia and Singapore (next to Taiwan, which is not in ASEAN) have some of the world’s largest semiconductor chip manufacturers, assembly and testing companies, and related outsourced services, and many are locally owned, notes Yusof Yaacob, Deutsche Bank’s Chief Country Officer for Malaysia and Head of SEA Investment Banking Coverage.

Four key influencers of growth

ASEAN countries account for 3.4% of the world’s GDP, but they contributed disproportionately more towards the growth rate of global GDP: 9% on average from 2012–2022.4 ASEAN countries constitute around 9% of the world’s population,5 and given that the majority of these people are young, the growth story will play on for quite a while yet.

In addition to demographics, four key themes stand out as drivers of further growth. flow spoke with experts from key ASEAN markets to understand these themes, and how they relate to recent changes in their home markets.

“ASEAN MNCs have been investors outside of their home markets for a long time”

1. Emerging middle classes and new consumers

These groups in Indonesia, the Philippines, Malaysia and Vietnam are all driving demand for telecoms, financial services and enterprise solutions in the automotive industry, and fast-moving consumer goods. Michael Chua, Deutsche Bank’s Chief Country Officer for the Philippines, provides one example of FDI into the ASEAN financial services and enterprise solutions sector. Deutsche Bank helped design and implement cash and FX management solutions for Mercedes-Benz Group AG’s subsidiary Mercedes-Benz Group Services Phils., Inc. (MBGSP). MBGSP is the group’s finance operations service delivery centre in the Philippines, with 1,000 people in two sites (650 headcount in Cebu City and 350 headcount in Clark, Pampanga), empowering different entities and business partners worldwide within the group to make financial data-guided business decisions.

2. Deepening financial markets

Local and regional financial markets are attracting domestic investors through insurance companies and asset managers, among others. This is likely to continue as the growing population, together with its emerging middle classes, gets more sophisticated. Rising demand in this area is evidenced by Deutsche Bank’s work on payment systems for Toyota Astra Financial Services, a joint venture in Indonesia between Toyota Financial Services and Southeast Asia’s largest independent automotive group. In addition, infrastructure financing (such as that earmarked for Indonesia’s new capital city, Nusantara) is attracting much FDI, adds Siantoro Goeyardi, Deutsche Bank’s Chief Country Officer for Indonesia.

3. Emerging local multinational companies

Flush with profits from their growing domestic middle-class consumer base, but having exhausted options in their home markets, emerging local multinational companies are going abroad to make additional investments. Take, for example, a business comprising five- or six-star hotels in a country such as Thailand with a population of 71 million; the options for expansion are somewhat finite compared to more international opportunities. The collective realisation of this – together with the stick of mature domestic markets and higher labour costs and the carrot of export market access – is both cause and effect of the fact that outward foreign direct investment stocks already accounted for 25% of Thai GDP in 2018.6

Pimolpa Suntichok, the bank’s Chief Country Officer for Thailand, points out that ASEAN MNCs have been investors outside of their home markets “for a long time” and that they are active purchasers of assets throughout the world. One example is the acquisition of Allnex, the industrial coating and resin producer headquartered in Frankfurt, Germany, by Thai petrochemical producer PTTGC. Deutsche Bank in Thailand and Germany worked swiftly and successfully for its Thai client to structure a cost-saving court-guarantee alternative to more traditional escrow arrangements, showing client and adviser both breaking free of capacity constraints.

4. Supply chain shifts

Much has been made of the trend of ‘nearshoring’ manufacturing capacity, but some of the shifts have been subtle and yet still significant. For example, ongoing tensions between the US and China are leading to supply chain reconfigurations from China into ASEAN countries, observes Huynh-Buu Quang, Deutsche Bank’s Chief Country Officer for Vietnam. While some of these moves may not appear to be seismic – moving production from China across the border into Vietnam, for example – the sense of sanctuary this shift to safety has given to manufacturers and investors alike is palpable. Adidas, Nike, Apple and Samsung are just a few examples of MNCs that have moved production from China to Vietnam.

Vietnam currently accounts for 50% of Samsung’s mobile phone production globally and is the world’s second largest garment and textile exporter, after China. However, Vietnam has already surpassed China to become the largest garment exporter to the US market.

Energy transition and rising demand

Just as companies have had to pivot to ensure supply chain resilience, so too are companies and governments in the region having to pivot their energy mix to ensure climate change resilience.

In September 2022, the International Renewable Energy Agency observed that the ASEAN region stands at a crossroads. “On the one hand, it can pursue a path of continued reliance on fossil fuels, most of which come from non-indigenous sources, increasing the region’s emissions and exposure to volatile and increasingly expensive global commodity markets. On the other, the region could utilise its ample, affordable, indigenous renewable energy resources to lower energy costs, reduce emissions and drive regional economic development.”7

Certainly, to continue its growth into the long term, the region needs abundant and secure energy. Continued investment in existing energy sources does still need to be made in addition to renewable sources as the transition progresses. For example, Thailand’s state oil company, PTT, has been busily acquiring Western assets, which helped it reach the rank of 177th in the 2022 Fortune Global 500. Despite the global momentum away from fossil fuels, there is still a high cost involved in rolling out renewable energy, and the incentives needed to accelerate clean energy transition pose a challenge for all governments – including those of ASEAN countries.

ASEAN companies are nonetheless showing initiative in seizing the opportunities provided by the energy transition. For example, Malaysia’s state-owned energy company Petroleum Sarawak Berhad (Petros) announced on 15 March 2023 that it had obtained its first licence for carbon storage to begin its strategic role as the resource manager for Sarawak’s natural carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CCUS) resources. CEO Janin Girie said that the development of the CCUS infrastructure “will unlock and commercialise the development of stranded sour gas reserves offshore Sarawak”. He continued, “The additional gas unlocked by CCUS can ensure long-term energy and gas supply security for Sarawak – complementing the energy transition for Sarawak and Malaysia.”8 The Malaysian state has also announced plans to export hydropower to Singapore9 and to produce green aviation fuel from algae.10

Another example of ASEAN outbound FDI is that of the Bangkok-listed RATCH Group, which has invested in Australia’s renewable energy capacity, in the form of six wind farms and one solar farm. Deutsche Bank helped RATCH with the refinancing of several of these renewable generating assets.11 As noted by Suntichok, another Thai group – Gulf Energy Development Public Company – owns a 25% interest in Germany’s Borkum Riffgrund 2 offshore wind farm (having reduced this from 50% at the end of 2022),12 which has the capacity to power around 460,000 German households each year.13

Forecast: continued flowering expected

When Samrit Chirathivat opened Thailand’s first department store in 1956, nobody could have predicted that the resulting Central Group, a family-owned conglomerate, would one day own Berlin’s flagship department store KaDeWe and co-own the London landmark store Selfridges.14 Such is the rate of the spread of ASEAN products, services and capital, one can safely predict that in the not-too-distant future, it will take a miracle for people to not see the blossoms produced by ASEAN’s hardworking and innovative companies and people.

Key facts: ASEAN

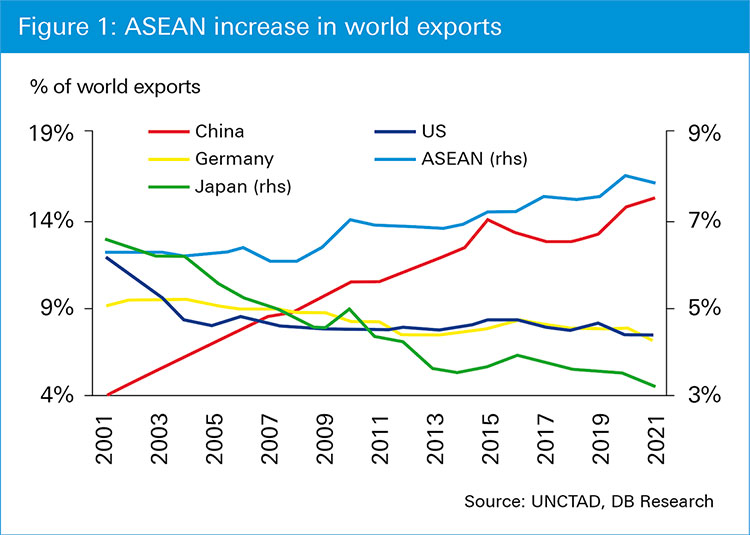

While intra-subregional trade is most significant, China is the number one destination for ASEAN’s exports, followed closely by the US. However, ASEAN continues to run a significant trade deficit with China but a surplus with the US. (See Figure 1.)

During the past decade, ASEAN enjoyed increased importance to global trade; its share rose one percentage point to reach 7.5% in 2019, with Vietnam leading the way. However, Vietnam’s rapid rise in technology-intensive manufactured goods was led by FDI from economies such as South Korea, long before the US/China competition, as MNCs sought more price-competitive locations.

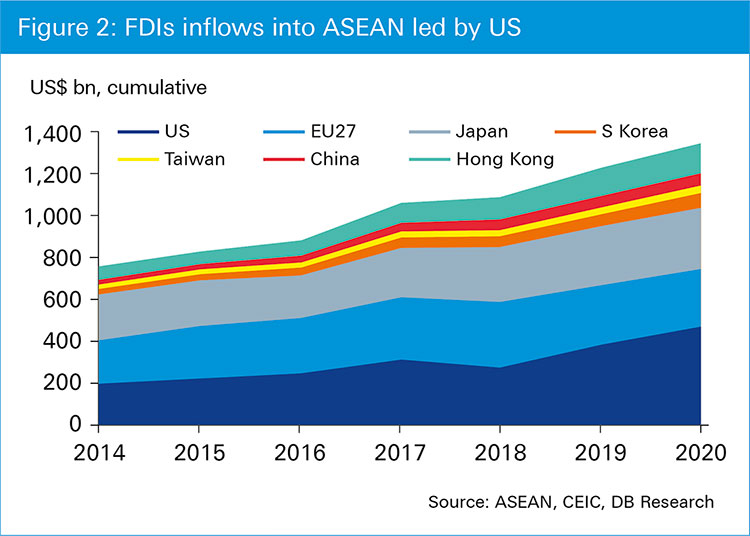

FDI inflows into ASEAN have risen sharply over the last decade, with Singapore leading the destinations. Despite strong headwinds from the Covid pandemic outbreak in 2020, the subregion’s share of world FDI inflow averaged 11.9% in 2019–21 – more than doubling from a decade earlier and almost on a par with China’s share of 12.2%, albeit lower than the 18% for the US. (See Figure 2.)

By sector, FDI inflows into ASEAN were dominated by financial, followed by manufacturing, then wholesale and retail trade and real estate – but, excluding flows to Singapore, manufacturing was the dominant industry sector.

The US stood out as the leading source of FDI inflows into ASEAN economies (Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam), with the financial sector as its top destination from 2012–2021. Japan followed, with its investment dominated by manufacturing – and well above FDI inflows from the EU.

Source: Asia Thematic Analysis, ASEAN and the China-plus-One strategy, 1 March 2023, Deutsche Bank Research

Sources

1 See worldbank.org

2 See asean.org

3 See ASEAN & the China-plus-One strategy, by Juliana Lee, Deutsche Bank Research, 1 March 2023

4 See worldeconomics.com

5 See sydney.edu.au

6 See oecd-ilibrary.org

7 See irena.org

8 See theborneopost.com

9 See thestar.com.my

10 See thestar.com.my

11 See country.db.com

12 See reuters.com

13 See power-technology.com

14 See selfridgespress.com